EDITION: ECOLOGIES.

The Government’s so-called Green Industrial Revolution is really a plan to subsidise the private sector in a period of low growth and dampened demand.

In November 2020, the Conservative government announced it had big plans for the environment. Prime Minister Boris Johnson committed himself to ten ‘pledges’ for a so-called Green Industrial Revolution. A short pamphlet – part misty-eyed press release, part policy paper – preceded a more detailed Energy White Paper from the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS). Johnson wrote a breathless foreword for the first of the two documents in which he asked readers to imagine a bright green industrial recovery from the Coronavirus pandemic – fuelled by British powers of innovation and imagination – rooted in the Midlands, the North and Scotland. It seems that the Green Industrial Revolution is less about collective solutions to the climate crisis, than a way to restore long-term private sector investments – and profits – in the wake of a disastrous Covid response and recession.

The Tories may have stolen Labour’s Green Industrial Revolution tag, but this is far from the latter’s vision of a democratised, publicly owned transition. The Tory government’s policy approach reflects recent trends in Britain’s political economy – as private sector contractors (including major fossil fuel polluters), the financial sector, and the state become locked into relations of mutual dependence. The ideological vision, meanwhile, is ripped not from the Labour Party of 2019, but its postwar productivist nationalism. As historian David Edgerton puts it, it was Labour that in the postwar period identified itself most strongly with regional industry – the North, the Midlands, the Clydeside, South Wales – against the financiers and rentiers of the City of London. Labour considered itself to be the representative of this ‘productive’ British Nation. The Tories’ Green Industrial Revolution echoes these concerns with nationhood, but funnels energy policy in the direction of finance and big polluters. It is a form of national productivism routed through private finance and with the working class airbrushed out. As Johnson puts it in the foreword:

We will turn the UK into the world’s number one centre for green technology and finance, laying the foundations for decades of economic growth by delivering net zero emissions in a way that creates jobs and allows us to carry on living our lives.

The vision expressed in Johnson’s “ten point plan” is one of electric vehicles and privately owned energy infrastructure – a green transition without disruption to the UK’s dominant models of ownership. A transition in which nothing fundamental will change and we will all be allowed to “carry on living our lives.” This is to be achieved not by any great expansion in public ownership, but by using public money to ‘leverage’ financial sector participation. This is a way of funding public services at least as old as the Blair government. What has changed is the centrality of this government-backed leveraging of private finance to the UK’s growth model in the wake of a Coronavirus crisis that has raised investor uncertainty and hit demand across a number of sectors.

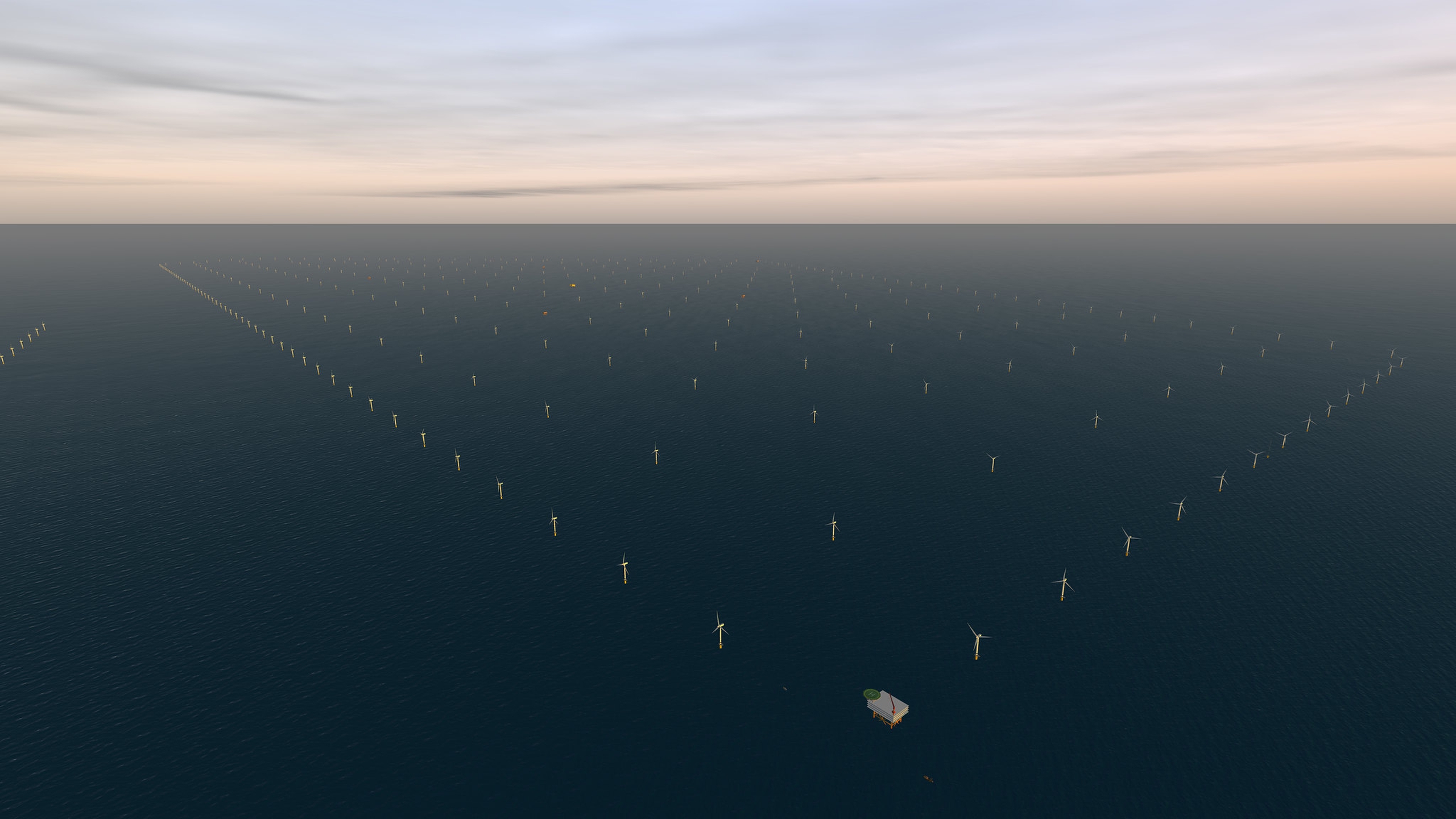

In its White Paper on Energy, the BEIS boasts of its success in reducing the cost of renewable energy supply to the national grid via its Contracts for Difference auctions. These contracts are offered on a competitive basis to prospective renewable energy suppliers. The government – operating through a separate company – offers to guarantee the future price of energy supply from offshore wind farms. Market prices for wind energy are prone to fluctuations as supply increases during bouts of windy weather. These contracts, therefore, ensure stable revenues to private energy companies. This, the government proudly states, incentivises financial markets to invest in UK renewable energy production.

Approaches like this have not been without success: UK energy supply is starting to transition from fossil fuels. But there are very real limitations to a narrowly defined transition of this kind. A strategy of leveraging private sector investment will always be reliant on the whims of financial markets – however supply prices are hedged. It places public money on the hook for private investment and is often more expensive than public ownership. It participates in the entrenchment of globalised financialisation, which has been the driving force in under investment in public services and infrastructure over the last few decades. Moreover, the government’s contract auctions actually funnel money into major energy suppliers who are – in some cases – still locked into the fossil fuel industry.

The government’s 2019 third round of Contracts for Difference auctions saw contracts awarded to the likes of the Sofia Offshore Wind Farm – a new wind farm to be located off the Teeside coast. The project is wholly owned by the German multinational energy company RWE – a fossil fuel polluter of global and historic proportions. Protestors in Germany have targeted the company in recent years for its still-significant involvement in coal. By guaranteeing stable future wind energy returns to publicly traded multinationals like RWE, the government is at the same time pushing up stock prices and maintaining equity markets. The British government’s allergy to public ownership, which is rooted in the interests they represent, means that while it has found a relatively successful way to incentivise some renewable energy production, questions of strategic control, necessarily linked to ownership, are sidestepped. Leaving the green transition in the hands of big private sector polluters risks slowing the pace of fossil fuel divestment.

Another contract winner was the Doggerbank wind farm: located off the English North-East coast, it will be the world’s largest offshore project of its kind. It is being jointly overseen by Scottish and Southern Energy (SSE) and Equinor. SSE is one of the Big Six UK energy companies, which emerged from the privatisation of UK energy suppliers after the 1989 Energy Act. It is a FTSE 100 publicly traded company and its shares are attracting interest from investors who want to cash in on the transition to a green economy. Equinor, on the other hand, is a Norwegian state-owned multinational petroleum producer. The role of SSE, in particular, reflects the privatisation mania of the British government since the 1980s. Instead of taking ownership of public infrastructure in order to ensure rapid decarbonisation, low consumer prices, and high renewable industry labour standards, government contracts (offered to the lowest bidder) encourage monopolising energy companies to cut labour and other costs. Moreover, the government is attempting to subsidise green investment without taking any prohibitive action against the continued use of fossil fuels by these same companies. Whatever the subsidy, such incentives are only effective for as long as market conditions remain positive and any economic disruption risks slowing the pace of transition.

The government’s Contracts for Difference auctions are an example of what may become an enduring feature of the political economic landscape of the UK. With high levels of investor uncertainty and disruptions to demand in the wake of the Coronavirus pandemic, such contracts offer a way to ‘leverage’ private sector investment by guaranteeing future revenues. On the one hand, these kinds of relations are not entirely new. Government has always subsidised strategic industries – this had a vital part to play in postwar Labourist productivism. But, in the era of the Coronavirus crisis, the fiscal, financial, and monetary capital circuits that link British government, corporate contractors, the financial markets, and central banks, have begun to play a more prominent role than ever before. Daniela Gabor has described this green financial strategy as the ‘Wall Street Consensus’. This consensus makes government support for the private sector central to plans for a green transition. It is, in Gabor’s view, a clear counter offensive to the popularity of more radical demands for a Green New Deal. Gabor is also clear on how detrimental these plans are for sustainability goals, particularly for the Global South. It is worth adding that where these plans are adopted, the emphasis on competitiveness drives a form of financialised green nationalism. The Tories’ Green Industrial Revolution is about putting Britain ahead of other countries. This competitive green nationalism undermines attempts in poorer countries to develop fixed capital as footloose financial investors flock to invest in what look like guaranteed returns to private energy providers in the Global North. Where the Labour opposition once called for climate reparations to Global South countries, the Tories are basing their transition plans in an ideology of competitive nationalism. The latter can be defined as a way of seeing the world — that is, a way of defining interests, objectives, and ways of achieving them — that privileges the British ‘nation’ as the primary beneficiary of moves towards a greener economic model. That conception of the ‘nation’, moreover, is one based on certain kinds of inclusion - a confluence of social interests organised around and adjacent to the dominant forces in the UK economy - and exclusion - principally, the global poor and working class. This conception of the nation - centred on the dominant capitalist forces in UK society - has guided the Tories as they have - however haphazardly - relaunched ambitious state-led projects.

In the UK, the Coronavirus pandemic has seen the return of very large public sector deficits as borrowing has risen to fund crisis measures and the recession has driven a fall in tax revenue. The government’s official position might be that such measures are temporary and borrowing will return to normal levels as soon as possible – that would certainly give them cover to impose austerity on the remains of the welfare state. But an alternative possibility is that – with increased uncertainty in financial markets and the risk of permanently lower demand across the economy – increased public spending will be relatively long-lasting. Those who support increased public spending frequently refer to that fact that government borrowing costs (in the form of interest paid on the bonds issued by the state) are extremely low. The reason for this is less familiar: the Bank of England intervenes in so-called secondary markets (where government and corporate debt securities are traded) – lending on favourable terms as well as purchasing assets outright. In doing so, the Bank of England plays both a market maker and liquidity insurance role. For example, it accepts collateral from financial markets – often government debt – in return for cash (so-called repo transactions), which maintains the existence of robust demand for debt. Gabor describes this as the ‘impossible repo trinity’ – a state of interdependence in which government debt plays a key role in financial markets, while stability is created through the support of the central bank for liquid repo markets.

Financial players – banks and institutional investors like pension funds and so-called shadow banks – use government debt and other assets as collateral to borrow cash, which finances investments in riskier, longer-term, higher yield securities. A steady supply of cash is therefore available to be plunged into corporate and mortgage debt – supporting both the ‘productive’ and real estate sectors. Government contracts – funded through government borrowing – form the other side of this equation. Large firms like the big energy companies mentioned above win government contracts, which practically guarantee them a profit as long as they deliver successfully. This attracts investment from financial market players – who often hold government bonds as relatively liquid assets that they can sell in the event that they need to exit a market and meet calls for cash. Government debt - backed by the central bank - plays a pivotal role in ensuring adequate liquidity in financial markets, and the latter are playing a central role as investors in businesses that are driving the UK’s green transition. This set of relationships - a gigantic public-private partnership - revolves around government debt and borrowing.

It is hardly a surprise then that the government’s announcement of its intention to launch a so-called ‘green bond’ (bonds issued specifically for financing green investment), was described by Chancellor Rishi Sunak as an opportunity to ‘renew the UK’s position as the world’s preeminent financial centre.’ The future of financialised capitalism runs through a government subsidised green transition.

This set of interdependencies should not be seen simply as the dominance of ‘finance’ over either the state or the ‘productive’ economy. It is rather what happens under capitalism when its fourth leg – that is, the organised working class – is removed from the equation. With little sign of union militancy or growth in union membership, there is no pressure on the state or employers to bargain directly with workers. Productivist nationalism of the postwar variety requires meaningful organisation by workers at the industrial and national level. What is emerging today is a set of state-market interdependencies centred on the exploitation of privatised services and infrastructure for the purpose of maximising returns to wealthy investors. Private markets are both made and backstopped by the state and the central bank – and the returns go to the wealthiest, who have the money to invest. With dampened consumer demand and a disorganised workforce, there is little scope for a more pro-worker rebalancing. You could call it green-washed, financialised nationalism.

It is ultimately this set of political-economic relations and the dominant sectors of the economy that underlies the Prime Minister’s Green Industrial Revolution pledges. On the one hand, the project is structured by these powerful private sector interests. It does all it can to make clear its commitment to ‘leverage’ public funds and to ensure their profits. On the other hand, it attempts to recontextualise these interests in a discourse of national purpose and renewal – one that can ‘unite’ the country in a common ‘struggle’. Global capital’s desire for a private-finance-backed ‘green recovery’ here combines with the government’s ideological project to unite their voting bloc – from cautious asset and property owners, pensioners and investors, to former Labour voters in the English ‘regions’ – around a project of national rejuvenation by financialised means. As is so often the case, this so-called green recovery will leave the real needs of both the environment and the global working class unmet.