EDITION: ECOLOGIES.

Histories of colonialism and extraction, told through their impacts on orangutans—and stories of red ape resistance.

For hundreds of years in the Global North, orangutans have led an independent life as symbols. For the philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau (who’d never seen one), they represented the state of nature in which we would all exist if deprived of human civilisation. For Edgar Allen Poe, in his Murders in the Rue Morgue, they seem to have represented the violence which, he feared, would be unleashed by the emancipation of enslaved people.1 Today, orangutans are put to other symbolic uses. For an animal that’s native only to Borneo and Sumatra, they’re never away from British billboards and TV screens for long. Back in 2011, an ad for British Airways displayed an orangutan beside the jaunty caption: “For just six glorious hours, he didn’t feel endangered at all.” A few years later, another orangutan popped up in ads for the energy company SSE, smiling beatifically in the sky as, below, a vista of turbines sprouted from the land like dandelions. (Of the UK’s 73 energy suppliers, SSE is currently ranked 44th in its use of renewables, which make up only 21% of its energy mix, so the unexplained sky primate wasn’t the only element that caused confusion.) More recently, the red ape has starred in ads for Amazon Audible, wearing headphones and a rapturous facial expression, like the primal chimps in 2001: A Space Odyssey, overawed by the monolith.

The fact that all of these companies are motivated by profit should be a given, and it would be a waste of time to chide them for being hypocritical—or insufficiently ecological—in their marketing campaigns. Images of orangutans are now deployed as signifiers of Nature and a state of innocent wonder, but they were only stuffed and wired into this symbolic cabinet after the comprehensive destruction of their real-world habitats—first by British and Dutch colonists, and then by the mode of production those colonists helped install through decades, if not centuries, of violence.

There’s a modest but healthy microclimate of UK charities devoted to orangutan protection, and they received a combined annual income of about £2.1 million at the start of 2018 and £2.2 million at the start of 2019.2 A number of other charities—such as WWF, Born Free Foundation, and International Animal Rescue—also engage in relevant conservation work, with some of their many fundraising campaigns focusing on the protection of these primates, so the total amount of money flowing towards the orangutan ‘cause’ is certainly higher. But a cultural and legal firewall has long existed between the domains of ‘charity’ and ‘politics’ in Britain, and, although charities are permitted to undertake certain forms of political activity, organisations that are deemed overtly ‘political’ in their purposes may be at risk of having their charitable status revoked. For all of the valuable work performed by these charities, their ability to attribute political factors to the question of orangutan survival is curtailed.

In The German Ideology, Marx describes Ludwig Feuerbach sighing over the fish deprived of their ‘medium of existence’ when their rivers are polluted by industrial waste, while having nothing to say about the specific social factors causing the damage. If we accept the legal firewall described above and content ourselves with sighing philosophically as ‘mankind’ deprives the orangutan of its forest ‘essence’, then our concern for the damage inflicted by the capitalist world-system upon non-human animals is excluded from a political realm of contestation, action, and solidarity, and restricted to apolitical, sentimental expressions of what could be called (with the greatest respect) ‘animal fandom’. Worse, it risks being swallowed up by generalised misanthropy (“we are the virus”), xenophobia (e.g. Britain First’s recruiting tactic of sharing concocted Facebook memes about Muslims or Romanians abusing dogs), or neo-Malthusian appeals to population control (as advocated, repeatedly, by various members of the British royal family).

In conservation literature, orangutans are often referred to as an “umbrella species” – a term for a particular animal whose protection has the knock-on effect of protecting large forest areas and other species. In the narrative that follows, this conceptual “umbrella” will be expanded, so that concern for orangutans entails or even demands solidarity with the Indigenous peoples of Borneo and Sumatra, as well as the exploited labourers on the islands’ vast plantations, and throughout the network that distributes the spoils of deforestation. Against the reactionary trend of blaming the looming extinction of ‘charismatic megafauna’ on the cruelty or ignorance of the human populations living closest to them, this article will trace a journey through the histories of the orangutans and their homelands, describing some of the ways in which capitalist institutions from Western Europe, the USA, and Japan have engineered their destruction.

Red apes in the web of life

Fossil records show that orangutans disappeared from China, India and the island of Java following the last ice age, between twenty and eighteen thousand years ago. This isn’t because they hitched their wagons and migrated in their ginger thousands to Borneo and Sumatra—these islands are, quite simply, the final, remaining outposts where orangutans haven’t yet died out completely.

Orangutans are most at home in the moist alluvial forest, where floods enrich the lowland soil with the nutrients needed for fruit to grow in abundance.3 In these wild habitats, they have been seen to develop regionally-specific culture’,4 learn skills from one another5, refer to past events, convey instructions, make requests, improvise a wide variety of tools for different tasks, collect a particular type of leaf to use as a hat when rain is imminent,6 make and apply topical ointments to relieve inflamed joints, and even decorate their tree-top nests, which they build to sleep in7. In some cases, sleeping orangutans have been seen to clutch small doll-like bundles of leaves that aren’t otherwise used for any ‘practical’ purpose.8

Though I am referring to orangutans by their standard Anglophone name, it’s important to stress that this name is itself a legacy of colonial violence. While the term ‘orang utan’ means ‘person of the forest’ in Malay, this name was not produced through centuries of close relation with humans, but rather was imposed by Europeans in the middle of the nineteenth century.9

Before this taxonomic imposition, they were known as maias or mawas, with separate names for those that are bigger or smaller, with long hair or cheek pads.10 The now-dominant use of ‘orangutan’ is a legacy of colonialism, and the underlying implication that forests are exclusively the domain of non-human animals—and from which all human beings are alienated—has long undermined attempts to reconcile conservation initiatives with the interests and knowledge systems of forest peoples.11 This linguistic tension cannot be escaped, but must nevertheless be acknowledged.

Though some of the Indigenous communities in Borneo and Sumatra would hunt and eat them, others observed a strict taboo against harming them, and would treat them as sacred.12 In the traditional belief systems of some Dayak peoples in Borneo, orangutans are thought to be reincarnations of respected community members, and the use of some plants for medicine is said to have been learnt from them. Iban people in Borneo recall that they ‘were told by their grandparents and great grandparents that they were helped by orang-utans during the ethnic war in the 1900s by driving away the enemies.’13 In one Dayak creation myth, the deities Iri and Ringgon were so pleased after creating humans that they celebrated through the night. When they woke up and tried to make more humans, they were so hungover that they created orangutans by accident. Though the implication that orangutans are the botched handiwork of hungover gods isn’t entirely flattering, it at least demonstrates a recognition of kinship, if not an equal relationship to the divine.

In captivity, orangutans have demonstrated an ability to communicate with humans through sign language,14 to make and use rudimentary tools, and—perhaps the most consistent of their behaviours—to escape from confinement. In his 2010 book Fear of the Animal Planet: The Hidden History of Animal Resistance, Jason Hribal describes the case of an adult known as Fu Manchu, who repeatedly broke out of Omaha Zoo in the 1960s and ‘70s. After a particularly baffling sequence of breakouts, zookeepers realised he’d been undoing a lock on his enclosure with a piece of metal wire he’d kept hidden inside his mouth.

In short, orangutans want to live, and they want to be free. Their ability to be free is denied not just when they’re locked in cages, but also when their forest homes are destroyed. They’ve always been affected whenever humans have fragmented their habitats by felling trees, establishing settlements, and clearing land for agriculture. But the character and scale of land-clearing has been neither constant nor consistent. It has been accelerated and magnified as the result of political and historical circumstance, rather than being an inevitable effect of humanity-as-such.

The East India Companies

Europeans first learnt about orangutans in the early 1600s, from the log books of merchant capitalists returning from the so-called ‘East Indies’. The Dutch East India Company (the Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie, or VOC) was set up to swell the capital of a rising merchant class by muscling in on the Asian spice trade. As some of the first ever ‘joint stock corporations’, the VOC and its English (later, British) rival sold shares on public stock exchanges, so their profits as well as their risks were shared with investors back in Amsterdam and London.15

In these early days of colonial pillage, employees of the VOC had an extremely low survival rate – only about one in three made it back home to the Netherlands.16 In an attempt to stem the flow of fatalities, in 1626 the Company recruited Jacobus Bontius as the Head of Surgery. The following year, Bontius sailed to what would later become Indonesia, in the company of Jan Pieterszoon Coen, who was heading out for his second term as colonial Governor-General. Coen, a zealous Calvinist who was largely responsible for the militarisation of the VOC, had recently overseen the extermination of 90% of the population of the Banda Islands (replacing them with trafficked and enslaved people from elsewhere in Asia17) for the sake of nutmeg.18

Coen and Bontius installed themselves in the ‘capital’, Batavia—which Coen had established during his previous term, after the destruction of Jayakarta, the city which had previously occupied the site. From that point on, Sumatra and Borneo and the other islands would act as peripheries to Java’s core—Batavia is now known as Jakarta, the capital of the Republic of Indonesia.

At the time of the colonial invasion, the people of Sumatra and Borneo either lived in ‘tributary’ sultanates or in relatively independent tribal groups in the interior.19 Like the feudal lords of Europe, the aristocracy of these coastal sultanates collected crops and forest products as a ‘tribute’ from the peasants and Indigenous tribes in the territory they laid claim to. The East India Companies would buy a share of this tribute—usually pepper—with gold or cotton extracted from elsewhere, and used a combination of violence and diplomatic pressure to secure a trading monopoly. The pepper was brought back to Europe and sold to the upper classes, who used the surplus appropriated from their own exploited workers to pay for it. Those who’d bought shares in the VOC (or the British East India Company) would then get their slice of the profits.

Most of Bontius’s time was spent in swabbing his colleagues and burying family members in a settlement besieged by a Javanese army—but, over the course of the four years he managed to survive (he died in Batavia, at the age of 39), he also wrote detailed accounts of the archipelago’s flora and fauna. In a chapter on the ‘Ourang Outang’, he claimed to have found the creatures that the Roman naturalist Pliny referred to as ‘Satyrs’:

According to the Javanese, they are able to speak, but choose not to do so, to avoid being forced to work… and it is said that they are the result of the lust of the women of the Indies, who slake their detestable desires with apes and monkeys.

Here, already, are several of the elements that would obsess Europeans for the next several hundred years: a queasy discomfort with the human/animal borderline; a prurient fixation on the sexuality of non-white women; and the tantalising prospect of expanding the unpaid labour force.

Pepper, cotton, gold

A few decades later, in the 1660s, the VOC established a base in coastal Sumatra. At this point, the sultanate of Aceh dominated much of the island’s trade, and the Company hoped to undermine it by entering the market in pepper and trafficked humans.20 Indian cotton had long been the dominant medium of exchange, but to buy this cotton, the VOC needed gold.21 To meet this need, a mix of Dutch and German supervisors established a mine at Salido, putting people abducted and trafficked from the nearby island of Nias, as well as from Timor, southern India, and Madagascar, to work as miners.

The clerk at the site, one Elias Hesse, didn’t bother to record how many of these three hundred and forty-five enslaved people lost their lives in the tunnels, but we can get a sense of the project’s violence from his report that only four out of twenty Europeans survived.22 Hesse also found time to write about the presence of orangutans:

The Orang Oetang, in size, shape, and intellect, are almost equal to man… they are very stout, swift, and bold: Around the mountain mine many of them have taken up residence, and when thunderstorms are expected they can be seen and heard with great displays and clamour… they are exceedingly lustful and love women, so that the latter pass through the forests in great danger of being impregnated by them.23

The only women present at the mine were enslaved; they were not local, and were unfamiliar with this landscape and its inhabitants. Whether this orangutan ‘threat’ was reported to Hesse by local guides or was a bizarre product of his fevered imagination, it can only have worked to deter any escape attempts that the enslaved women may otherwise have been tempted to launch. Another notable feature of this passage is the assumption that these women were physically capable of being impregnated by orangutans. Hesse didn’t elaborate on this point, so we can’t know if he would have assumed the same about European women.

Much of the VOC’s profit was seized in direct competition with its British counterpart. Both of them had been sniffing around the ports of Banjarmasin in Borneo since their incorporation, fighting for the pepper that was grown on the riverbanks of the interior. At first the Banjarese collected their pepper from the Indigenous Dayak cultivators who lived upriver, and sold it to whichever of the European trading companies was currently in favour. When prices dropped in the middle of the seventeenth century and the Dayak growers chafed against pressure to neglect their subsistence crops in favour of producing more pepper (which exhausts the soil) to make up for Banjarese losses,24 the Sultan of Banjar addressed the problem by establishing his own permanent plantations in the alluvial fans of Hulu Sungai, with the pepper now being grown by Banjar-Malay peasants, under the control of the sultan.25 However small in comparison to the deforestation imposed under Dutch colonialism, in both cases the clearance of land “was extended by a nobility heavily involved in the export trade,” rather than by peasant farmers growing for domestic consumption, or Indigenous subsistence smallholders.26

Throughout this time, the Companies continued to publish reports of their voyages, often containing descriptions of local wildlife. In 1718, a Company merchant called Daniel Beeckman wrote that, while visiting Banjarmasin, he’d purchased an orphaned orangutan “out of curiosity, for six Spanish Dollars”. Orangutan mothers do not voluntarily leave their children, so the existence of this orphan may function as an indication of the pepper trade’s encroachment on the habitat of the apes. Beeckman wrote of his purchase:

it lived with me seven Months, but then died of a Flux [dysentery]; he was too young to show me many pranks, therefore I shall only tell you that he was a great Thief, and loved strong Liquors; for if our Backs were turned, he would be at the Punch-bowl, and very often would open the Brandy Case, take out a Bottle, drink plentifully, and put it very carefully into its place again… If at any time I was angry with him, he would sigh, sob, and cry, till he found that I was reconciled to him… [He] was but about twelve Months old when he died…27

In 1762 another English merchant recorded an encounter with a young ape. Reprising the longstanding fantasy of enslaved Malay women having sex with animals, he recounted speculation that

the cruelty of the Dutch to their Malayan female slaves, often obliged them to fly into the woods to escape the cruelty of their tyrannical masters; and, being forced to live there solitarily, it was thought that they might, by length of time, turn mad, or insensibly brutish, and might have yielded to an unnatural commerce with some animals in the woods, by which this strange animal I have been speaking of was produced.28

As can be seen, European scholars were still at this point debating whether orangutans were just a debased form of human being, an end point on a sliding scale—a vexed topic, which included the question of whether they did (like humans) or did not (like all other beings) possess souls. The matter wouldn’t be settled until 1770, when a Dutch anatomist concluded that they were a wholly distinct species. In the meantime, this recurring trope of East Indies women mating with apes expressed a Dutch and British belief in their biological closeness, at least as much as it expressed a recognition of the apes’ similarity to ‘human beings’ in general.

The Companies made extensive use of forced labour during this period, which coincided with the emergence of ‘Enlightenment’ principles of equality and ‘natural rights’. By categorising enslaved and colonised people as something closer to ‘soulless’ ‘animals’ rather than humans, European colonisers neatly avoided having to extend the principle of equality to those whom they were exploiting. John Locke, the quintessential philosopher of ‘natural rights’, funded his philosophical production through investments in the Royal African Company of human traffickers, as well as his co-ownership of a plantation investment company called Bahamas Adventurers.29

Though the claim about “the cruelty of the Dutch to their Malayan female slaves” was accurate, the fact it was made by an English merchant is ironic in light of the extensive and brutal use of enslaved labour on British-run plantations across the globe. As Sidney Mintz has argued, because plantations were “frontier institutions”established in regions where the British were greatly outnumbered by those whom they had enslaved, they “could survive only by the use and threat of violence… and saw the use of violence as their duty, to keep and restore order.”30 In response to the increasing frequency of revolts by enslaved plantation workers (such as ‘Tacky’s Revolt’ in 1760), Edward Long, a rum-soaked British administrator in Jamaica, made the apparently serious suggestion that “an oran-outang might, with a little pains” be trained to perform the plantation work instead.

“A burlesque on human nature”

The first orangutan to survive the voyage to Britain was a young male from Borneo. When the Netherlands was invaded by Napoleon, the British, under Stamford Raffles, seized control of the ‘East Indies’. The Sultan of Sambas presented Raffles with a young ape, as a sort of gift or tribute.31 He was taken to Java, where he was handed over to an English surgeon, Clarke Abel, and shipped back to London. According to Abel, early attempts to confine him were unsuccessful:

On board ship an attempt being made to secure him by a chain tied to a strong staple, he instantly unfastened it, and ran off with the chain dragging behind; but finding himself embarrassed by its length, he coiled it once or twice, and threw it over his shoulder.32

They soon gave up and let him freely wander the ship, where “he commonly slept at the mast-head, after wrapping himself in a sail.” He formed a particular bond with the boatswain, “who shared his meals with him, and was his chief favourite, although he sometimes purloined the grog and the biscuit of his benefactor… and he might be often seen sitting at his cabin-door enjoying his coffee, quite unembarrassed by those who observed him, and with a grotesque and sober air that seemed a burlesque on human nature.”33

On arriving in London, he ended up in a ‘menagerie’ that members of the public could visit, and where the animals were kept in cramped metal cages.34

Orangutans’ genetic closeness to human beings leaves them vulnerable to disease transmission from humans, and the crowds of up to 300 that came to peer at him in his cage on a daily basis meant that he soon picked up an infection. In his last weeks of life, desperately unwell, he was taken on carriage rides through the streets of Georgian London, wrapped up in “a countryman’s smock frock” and hat.35 He died a long way from the forest, and his body was stuffed and put on display in a museum.36

The Colonial Era

By the time the East Indies was ‘returned’ to the Dutch in 1814, the VOC had finally been dissolved. Its holdings were appropriated by the state, whose functionaries were increasingly influenced by the ‘Enlightenment’ thought coming out of post-Revolutionary France.

One such thinker was Guillaume-Thomas Raynal, who inspired the Dutch reformer Dirk van Hogendorp to transition from merchant capitalism to outright colonialism.37 Raynal decried “the effeminacy and corruption to which the Dutch have abandoned themselves”, and advised discarding the VOC’s monopolistic practices in favour of free trade and ‘laissez-faire’.

Van Hogendorp may have been especially receptive to this message, since his hopes of personal enrichment through opium trafficking had been dashed by the British Governor-General in India, who had “curtailed the trade in opium, and thus has caused my financial ruin”.38 If this experience in India deepened Van Hogendorp’s preference for free trade over monopoly, it also, contradictorily, convinced him of the virtues of the land tax system, which had been introduced to India by the very same British Governor-General.

On the basis of Van Hogendorp’s advice, and the principle of a ‘national sovereignty’ that extended far beyond the borders of the Netherlands, the new administration started making radical changes. At first this was done through roundabout measures to undermine the power of the sultanates, e.g. by imposing a land rent that was directly payable to the Dutch government as cash, and by encouraging a class of rural proletarians to sell their labour in a free market. The colonial government then decreed that those plantations which had been sold into private hands under Raffles must be returned to the Javanese nobility, and that these nobles must pay compensation to the private owners. In Yogyakarta, the plantation owner due to receive compensation had also been the local Dutch representative, Nahuys van Burgst, which went down about as well as could be expected. The treasurer of the court in Yogyakarta, the popular noble and devout Quranic scholar Diponegoro, had already taken a dislike to this representative/plantation-owner, who, he complained, ‘merely enjoyed eating and drinking and the spreading of Dutch ways’. But under the new rules, he was now expected to reimburse van Burgst for the coffee and pepper plantations that had just been returned to the sultan.39 These impositions outraged both the peasants and the Javanese nobility, and eventually the Javanese, led by Diponegoro, went to war against the Dutch. The Java War raged for five years, from 1825 to 1830, and would claim 200,000 lives (192,000 of whom were Javanese).40 Nahuys van Burgst, meanwhile, went on a gap year to India, and then returned to the Netherlands to enjoy a comfortable retirement.

In 1827, halfway through that war, a report was delivered to the Asiatic Society of Calcutta. It described an encounter between British sailors and a wild orangutan, after they landed on the north-west coast of Sumatra. Startled by their appearance, he had quickly climbed a tree to get away. Rather than continue about their business, the sailors decided to use up all their bullets in an effort to kill him:

… it was only by cutting down one tree after another, that his pursuers by confining him within a very limited range, were enabled to destroy him by several successive shots, some of which penetrated his body and wounded his viscera… It is stated by those who aided in his death, that the human-like expression of his countenance, and piteous manner of placing his hands over his wounds, distressed their feelings, and almost made them question the nature of the act they were committing.41

The report—which does not mention why the sailors chose to do any of this—is notable for its demonstration of the pointless, murderous cruelty and environmental destructiveness of the perpetrators, and, relatedly, for its demonstration that the British were still competing for the riches of Sumatra, and were prepared to assert their entitlement by the most violent of means.

A reserve army of orangutan labour?

With the abolition of slavery in British colonies around this time, the Caribbean sugar industry suffered a major blow, and the Dutch cashed in by introducing the ‘Cultivation System’, forcing Javanese farmers to turn their rice paddies into sugar cane fields.42 Under this system, the Javanese nobility were restored to some of their former eminence, being given the title of ‘Regents’, which helped to head off the possibility of any further cross-class solidarity of the sort that had led to the Java War. The peasants, meanwhile, were now required to grow a compulsory, pre-agreed volume of export crops for the Dutch government.43 According to one estimate, the Cultivation System obliged peasants to perform ‘four or five times the amount of labour customarily demanded before 1830’.44 The resulting exports of coffee and sugar were extraordinarily profitable, and helped the Netherlands fund their colonial expansion into Borneo and Sumatra. In the meantime, the British kept up a stubborn presence on both of the islands.

In 1838, a British ship returned to London with a live orangutan, known as Jenny, onboard. She became the first orangutan at London Zoo, where Charles Darwin was a regular visitor to her enclosure. In his notebooks, Darwin marvelled at Jenny’s intelligence and playful behaviour. These encounters with Jenny helped cement his conviction that human beings are not separate from other animals, as was then commonly believed, and that ‘intermediate species’ like orangutans might help us situate ourselves within the rest of the ‘animal kingdom’.

While Darwin communed with this captured child of Borneo, an Englishman called James Brooke used the money he’d just inherited from his father (a colonial judge in India) to buy a heavily armed schooner, and promptly set sail for the island’s northern coast.45 On arriving at the mouth of the Sarawak River, he won the favour of the Sultan of Brunei by crushing an uprising on his behalf. The Sultan was so grateful, in fact, that he recognised Brooke as the legitimate ruler of Sarawak—though the promise of annual payments out of the wealth that the Brooke family had extracted from India probably sweetened the deal. Having read about orangutans, Brooke—who referred to himself as a ‘White Rajah’—wasted no time arranging a trip to hunt them. His accounts of the apes whom he encountered express a seething contempt for ‘slothfulness’ that, while undoubtedly a familiar component of the Protestant ethics of the time, is nevertheless jarring to read in reference to an other-than-human being:

The adult male I killed was seated lazily on a tree, and when approached only took the trouble to interpose the trunk between us, peeping at me, and dodging as I dodged… I may remark, that they are as dull and as slothful as can well be conceived, and on no occasion when pursuing them did they move so fast as to preclude my keeping pace with them [and] they were sure to stop and allow us to come up.

Orangutans have a famously slow ‘life history’. Mothers raise their children for the first eight years of life—the longest weaning period of any non-human mammal—and will not give birth again until this nursing period has finished. This slowness is also reflected in their day-to-day behaviour. Compared to other primates, they are noticeably slow-moving and watchful; the only other mammal that uses less daily energy is the sloth. Biologists suggest that orangutans have evolved this gentle pace of life in response to food scarcity, since the frantic energy of a bonobo or chimpanzee couldn’t be sustained on orangutans’ austere, mostly vegetarian diet. Though the first Europeans to hear of orangutans maintained a vague hope of enslaving them (recounting the belief that “they are able to speak, but choose not to do so, to avoid being forced to work”), this hope was dashed once the British and Dutch established a more permanent colonial presence in Borneo and Sumatra. Familiarity soon revealed their unsuitability for this kind of project, and so removed the promise of yet another source of unpaid labour.

If colonists like Brooke had to abandon the prospect of a reserve army of orangutan labour, they could least make a little money by exporting them to Europe—dead or alive. For every orangutan captured alive, at least one more would be killed in the forest and dismembered so that its body parts could be pickled and peered at by European physicians. From 1840 to 1848, between 100 and 150 of them were captured and brought to the coast every year, of which (on average) only 5 survived as far as Europe.46 So, for every 5 orangutans that reached a European menagerie, between 200 and 300 may have been killed.

Every animal shipped to Europe from the tropics was to some extent displayed as a trophy of imperial conquest, but, for James Brooke, this wasn’t even a subtext:

Great was our triumph as we gazed on the huge animal dead at our feet,” he wrote, “and proud were we of having shot the first Orang we had seen, and shot him in his native woods, in a Borneo forest, hitherto untrodden by European feet.47

Rubber and oil

The turn of the twentieth century heralded what the conservationists Meijaard and Rijkson have described as:

The most devastating impact on the historical range of the orang-utan in Sumatra… when the vast lowland forests… were converted, first into tobacco-, then into rubber- and, more recently, into oil-palm plantations.48

The seeds of this destruction were sown in 1865, when the Dutch government passed a law granting themselves exclusive rights over all of the forested land within ‘their’ territory. They replaced the Cultivation System with the Basic Agrarian Law, which, in a classic Lockean-colonial move, redefined as ‘empty’ all land that wasn’t being cultivated (and cultivated in ways that were recognisable to Westerners as such). Technically, this only applied to Java, but a booming global timber trade, combined with the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869, meant that foreign firms took the new legislation as a green light to descend on eastern Sumatra and compete for land rights (known as ‘concessions’) from local rulers.

These foreign firms established their plantations and mining sites, after a period of violent colonisation, in the final years of the nineteenth century. Royal Dutch (now known as Shell) was founded after oil was discovered in Sumatra in 1885; this oil was then extracted using staff and equipment from the USA.49 But significant oil reserves remained inaccessible as long as the longstanding conflict with the Sultanate of Aceh dragged on, so the Dutch military launched a new and ruthless campaign to clear a path to the oil fields.50

In 1904 they launched a series of further ‘pacification’ campaigns, killing the Sultan of Jambi, and using the occasional harassment of European planters and Christian missionaries as an excuse to invade and build a road from the existing lowland plantations, through the Karo highlands, and into Aceh.51 With Sumatra effectively conquered, the ‘Kolonosatie’ (“colonisation”) programme was launched in earnest, and masses of landless Javanese workers were shipped over to staff the plantations.

The port at Belawan was built by the Dutch in 1890 to export tobacco, and was later expanded for the export of rubber and palm oil from Sumatra’s expanding plantation belt. This was achieved through extensive lobbying by two European companies.52 The first of these was the British outfit Harrisons & Crossfield, and the other was SOCFIN (Société Financière des Caoutchoucs, or Rubber Finance Corporation). SOCFIN was established by a Belgian called Adrien Hallet, who’d made his fortune in Congo under King Leopold II’s bloody rule, the death toll of which has been estimated at 10 million people.53 His move to Sumatra—and the fateful introduction of the oil palm to its ecosystem—was not unrelated to the violence of Leopold’s regime. The Belgian king had purchased ‘concessions’ in African territory under French control, and Hallet managed the large Mpoko concession—in what is now the Central African Republic—on his behalf. When, in 1905, a French commission started investigating reports of mass murder and torture on the Mpoko concession Hallet began to look for investment opportunities elsewhere in the world. He continued to collect his Mpoko dividends right up until the concession was voided in 1910, when inspectors established that around 2,000 murders had been committed at the company’s behest.54 The company went into liquidation in 1911, and Hallet established his first plantation in Sumatra the very same year.55

In Borneo, the colonisation drive had always been spurred on by competition between the British and the Dutch. With the British North Borneo Company and the ‘White Rajah’ of Sarawak extending British control across the north of the island, a number of Dutch companies began to appeal for mining rights. Colonial officials didn’t intend to forego the considerable tax revenues these private initiatives promised to deliver, and one by one the remaining sultanates were forcibly brought under Dutch control.56 In 1907, Royal Dutch entered a partnership with Shell, and their subsidiary, the Anglo-Saxon Petroleum Company, struck oil in Sarawak. This caused a boom for the town of Miri, and for Shell, which employed the father of Sarawak’s future Governor, Abdul Taib Mahmud—who would later be given a university scholarship in Australia, under a Cold War initiative called the Colombo Plan.57 The Colombo Plan was a joint scheme between Australia and Britain, partly funded by the US, which aimed ‘to convince political elites and the population [in Asia] that communism was not in their interests’.58

The Plan was, to all intents and purposes, entirely successful in convincing Taib of the evils of communism and the virtues of personal enrichment.59 In 2009, a leaked cable from the US embassy in Malaysia stated:

Chief Minister Taib remains unchallenged after 27 years in office, his government doles out timber-cutting permits while patrolling the under-developed state using 14 helicopters, and his family’s companies control much of the economy.60

The personal wealth Taib has accrued from his exploits was, in 2012, estimated to total around $15 billion. Much of this wealth, according to articles in Asia Sentinel, Sarawak Report and the Financial Times, is allegedly parked in the London property market, via the British Virgin Islands and a company called Ridgeford. For the sake of balance, we should also note that a retraction and apology published by the intrepid Fitzrovia News included the following acknowledgement:

Claims that Ridgeford was part of a multi-billion property empire controlled by the Chief Minister of Sarawak, that this empire gained from the proceeds of illegal timber in the Malaysian State, and that Ridgeford’s Bolsover Street development was part-funded by such illegally obtained money… are entirely without foundation.

Nevertheless, we can see clearly that the creation and solidification by Global North powers of national elites which serve colonial interests is an historical and ongoing process.

By 1913, the colonial division of Sumatra had established itself: the French and Belgians specialised in extracting palm oil, American companies focused on rubber, the British on tea, and the Dutch on tobacco.61 As the roads were widened, and the plantations (and their labourers’ satellite villages) subtracted around 10,000 km² from the forests, orangutans were left exposed. Many were either killed as agricultural pests, or sold into the flourishing wildlife trade.62 Though the colonial government were vaguely conscious of the protective moral cachet that conservation strategies might bring to their administration, following the example of King Leopold’s wildlife protection pledge in the Congo,63 orangutan protection was still very far down their list of priorities.

In order to maintain a steady supply of land for private companies, the government introduced the 1927 Forestry Decree, whereby traditional ‘adat’ land rights were overtly disregarded, and Indigenous lands were re-designated as ‘state forest’. A hunting ordinance now forbade the hunting of orangutans—an anti-Indigenous piece of legislation that attributed greater harm to small-scale subsistence hunting than to the forced transformation of forests into plantations. However, this law still permitted the export of orangutans—perhaps because, while subsistence hunting didn’t generate profits for the colonists, the export trade certainly did.64 Any apes that ‘trespassed’ on plantations or in the new ‘state forests’ continued to be met with either death or capture; and those which were captured were typically shipped overseas.

In the years preceding World War II, just under half of all exports from the east coast of Sumatra went to the USA (75% of the US supply of palm oil and 46% of all Sumatra’s rubber),65 and many orangutans joined these products in the cargo hold.66 Apes were also sent to Europe: in 1927, a ‘Dutch Indies’ newspaper reported the export of a ‘family’ of Sumatran orangutans (a mother and child, accompanied by an adult male known as Wambo) to a zoo in Düsseldorf. The three apes, for whom the zoo had paid 20,000 marks, had been shipped to Germany by the same firm that exported apes to the USA. The boost in attendance which resulted from the presence of the orangutans reportedly earned the zoo 60,000 marks.67 Orangutans were profitable business.

Working conditions on the plantations were poor, and estate workers frequently staged rebellions. Panicked by the scale of the rebellions, plantation owners, convinced themselves that the Communists were behind every act of disobedience. These fears weren’t entirely baseless. While the fieldworker uprisings emerged from spontaneous organisation against unthinkable oppression, there was also an incipient Javanese labour movement emerging at roughly the same time. The Partai Komunis Indonesia (Communist Party of Indonesia, PKI) had recently grown out of an organisation founded by Dutch social democrats (the ISDV), and its membership began to rapidly increase due to an influx from Sarekat Islam (a Muslim mass movement that had developed in the batik industry in 1911). From the 1920s onwards, the PKI was engaged in trade union activity, organising, unifying, and coordinating the disparate labour movements. Needless to say, this development was not welcomed by the plantation owners.

This atmosphere of paranoia around the empowerment of workers was bolstered by a newly-founded fascist group, the Vaderlandsche Club (Fatherland Club), whose members occupied key positions in the colonial administration.68 But the fascist response to the worker’s movement wasn’t confined to this group. The Nazi Party was firmly established in the Dutch East Indies, under the supervision of one Walther Hewel. Hewel had participated in the Munich Beer Hall Putsch in 1923, carrying a swastika banner alongside Himmler and Hitler. After a brief spell in Landsberg prison, where he volunteered himself as a sort of servant to Hitler, he undertook an apprenticeship in Hamburg and then moved to London. He got a job with Anglo-Dutch Plantations Java Ltd, and travelled to Java, where he became his plantation’s Chief Assistant. He also joined the local Nazi Party and became one of its most enthusiastic organisers. The Nazi Party’s ‘National Group Leader’ in the region was also an estate administrator, at the Kemondong Plantation in southern Sumatra. Emil Helfferich, publisher of the Nazi-supporting German-language colonial magazines Deutsche Wacht, Deutscher Bund, and Deutsche Haus, was a trader in Sumatran pepper. Helfferich would go on to become a member of the ‘Keppler Circle’—prominent Nazi industrialists who supported Hitler’s rise to power—alongside the heads of IG Farben and Reichsbank president Hjalmar Schacht. Fascism and colonial extraction were deeply intertwined.

With the government, the planters and the colony’s home-grown fascists all distracted by the communist threat, the non-communist, pro-independence Partai Nasional Indonesia (Indonesian National Party, PNI) was established, under the leadership of future president Sukarno. Recruitment to the nationalist cause was boosted by the Great Depression, when mass redundancies on the Sumatran plantations (it’s estimated that the workforce decreased from 336,000 to 170,500 in just a few years) led to the forcible repatriation of thousands of Javanese workers.69

These angry and dispossessed people swelled the ranks of the PNI—alarming the colonial authorities, who imprisoned several of its major figures, including Sukarno. Others, such as Mohammad Hatta, were exiled. Without its leadership, and subject to a harsh crackdown that inhibited organisation, the emergent nationalist movement all but fizzled out, with the original PNI disbanding in 1931—but the colonisers were rattled.

During the 1930s, casting about for a means of justifying their ongoing and increasingly unpopular rule, the colonial government developed a sudden interest in ‘conservation’. They pointed to examples of alleged ‘mismanagement’, such as a Bornean sultan who’d helped arm some rhinoceros hunters, to argue that only they, the Dutch, could be trusted to safeguard native wildlife. As a result of this PR assault, the Leuser wildlife reserve in southern Aceh was established in 1934; and it continues to protect one of the last wild ranges of Sumatra’s remaining orangutans. It could not, however, protect the Dutch authorities. In December 1941, the Imperial Japanese army invaded Borneo, with Sumatra falling a few months later. As the colonial authorities fled, they abandoned their prisoners, including Sukarno, who was promptly courted by the invading Japanese. Though the Dutch would not recognise an independent Indonesia until 1949, the colonial period was over.

The Japanese Occupation.

Japanese agents had been active and effective in the ‘Dutch East Indies’ for many years. Some of them had worked as shopkeepers, and Australian intelligence reports in 1942 complained that they ingratiated themselves with local communities through such dastardly means as treating “their native clients with particular friendliness,” and “the native races as equal”.70 When the Imperial Japanese military overthrew the Dutch colonists (with an ease that decisively showed the supposed superiority of the European rulers to be an illusion), the Japanese Prime Minister, well-informed on the incipient nationalist movement, promised that the people of Java, Sumatra, and Borneo would be equal participants in political life. In reality, however, hundreds of thousands of Indonesians would die and suffer terribly during the Japanese occupation.

Japanese businesses had long been investing in the deforestation of Borneo, and this continued throughout the military occupation. Before the invasion, zaibatsu (a type of vertically-integrated conglomerate specific to Imperial Japan) such as Kuhara and Nomura already ran rubber plantations in British North Borneo, and the companies Kubota and Borneo Shokusan Kabushiki Kaisha (Borneo Industrial Development Co.,Ltd.) had a footprint of about 8,500 hectares between them. When Kuhara collapsed, the new colonial-era zaibatsu Nihon Sangyō Kabushiki Kaisha (Japan Industrial Co.,Ltd.), better known as Nissan, took over their plantation. By 1939, Nissan had converted almost 45,000 hectares of land for hemp and rubber production.71

The zaibatsu weren’t the only ones decimating the forests. In 1937, the Japanese Governor-General in Taiwan devised a scheme to bring 2,000 Japanese families to Borneo to run abacá plantations. 27,700 acres of forest were bought so that these settlers could learn the art of ‘forest-clearing’ and convert the land into estates. Once they’d honed their ‘skills’ on this ‘practice’ forest (though the actual forest-clearing work was, perhaps inevitably, performed by Indigenous workers), the settler families moved on to establish their own plantations.72

Most of the timber cut down in British-run northern Borneo was shipped to Hong Kong by the British North Borneo Company, whereas logging in ‘Dutch’ Borneo was dominated by Japanese businesses. A Japanese logging project run by Seiji Ide and his backer, the Tōkyō-based Oriental Development Company (ODC), had a 1,000 person workforce cutting down trees in Bulungan, and the Dutch gave them rights to a further 50,000 hectares of forest along the Sankulirang River. They hired thousands of Dayak to carry out these operations, paying them poorly, working them hard, and keeping them confined in barbed-wire camps. Their treatment of the Indigenous workers in the course of destroying their forests was apparently so severe that, in the years between 1935 and the Japanese invasion, the crumbling colonial government was moved to intervene. A more Dutch-friendly Japanese company called Nanyō Ringyō Kabushi (NRK) were brought in as managers, although the labourers’ working conditions were scarcely improved.73

Militarising the forests

During the Meiji period (1868-1912), orangutans had begun to appear in Japanese zoos. They were given the name 猩々 (shōjō), which referred to a type of 妖怪 (yōkai, folkloric supernatural beings or phenomena). Shōjō were said to be red of hair and face, to be gentle and shy, and to be incredibly fond of sake in large quantities. This choice of name led to certain amounts of confusion when the Japanese public finally encountered captive orangutans. In a letter to a newspaper editor, one zoo attendee complained that “it didn’t speak as it has been written that it should in the [Zhou dynasty text] Book of Rites, and it didn’t drink sake as Noh songs say it does… is there no such thing as a shōjō that can speak and drink sake; is that a lie?”74

This disenchantment only deepened as the country modernised, and by World War II, as Daniel Wyatt writes,

the public’s view of foreign animals as creatures of awe and as quasi-spiritual beings shifted towards seeing them as objects of human rule and symbols of ‘the conquest of foreign lands.75

By the time the Japanese military invaded Indonesia in 1941, their attitude to the forest and its dwellers, both human and primate, would be on a par with the European colonialists before them. Logging operations accelerated during the occupation, and labourers from Java, as well as Iban and Dayaks, were forced to cut down thousands of tonnes of timber for boat-building.76

The occupiers had immediately recognised the importance of the Sumatran plantations for the greater war effort, and a merger of Japanese private companies called the Federation of Agricultural Estates (Nōen Rengōkai, or NRK)77 was appointed to run them. The NRK recruited advisers from the Dutch planters’ association, AVROS—an organisation notable for having teamed up with the Indies Intelligence Bureau to crush the 1920s wave of labour unrest. Among these advisers were administrators from the Dutch company HVA (whose plantations then covered 90,000 hectares),78 the US rubber producer HAPM, and the palm oil producers SOCFIN.79 With a view to the postwar ‘business environment’, these advisers urged the NRK not to disrupt the profitable labour regime that had been established by colonialism. The NRK agreed.

As we have seen, US geologists had found oil deposits in Sumatra back in the 1930s—but by the time the US company Caltex had managed to strike oil (encroaching still further into the forests in the process), the Japanese invasion had begun. The occupiers were quick to pick up where Caltex left off, drilling wells and forcing Sumatran labourers to dig pipelines, roads and railways from those wells to the coast, where fleets of Imperial warships and fighter planes were waiting. Around 300,000 conscripted labourers were brought over from Java, of whom 223,000 died in the efforts to bend the island’s swamps and forests to the will of the Japanese military, which failed to even provide them with sufficient food and medical care by way of return.80 Of the 100,000 people conscripted to build the notorious ‘Sumatra Railway’ during the war, around 80,000 died of disease or malnutrition.81

The Martyrdom of the Wild Beasts

Not much is written about orangutans during the war, though we can surely infer the effects the aforementioned deforestation and bombardment must have had on them. There exists one record of starving PoWs trapping and killing an orangutan for food—apparently, they couldn’t bring themselves to eat it once they saw how much its anatomy resembled their own.

Beginning in 1943 with the ‘Great Zoo Massacre’ at Ueno Zoo in Tōkyō, the Japanese state embarked upon a controversial programme. As a means of signalling to the public that the time for total sacrifice in the name of victory was close at hand, all large animals kept in zoos within Japan were to be slaughtered. To cement this solemn sense of duty, elaborate memorial services were held to commemorate the 殉難猛獣 (junnan mōjū: ‘the martyrdom of the wild beasts’).82 In 1944, as the course of the war shifted in favour of Allied forces, Japan’s colonial zoos in Taipei, Seoul, and Manchuria began to follow suit. One of the victims of this policy was an orangutan known as Ichirō, an inmate of Taipei Zoo who had become a celebrity in 1936, when his photograph was submitted to a competition held by Ōsaka Zoo. The zoo dubbed him ‘Japan’s Number-one Orangutan’—a casual but effective assertion, as Seeley and Skabelund note, of Taiwan’s subordination to Japanese rule.83 The Taiwanese writer Yang Yunping, perhaps picking up on these undertones, composed the following poem from Ichirō’s perspective:

All day long, I grab the iron bars of my cage, and rock back and forth

That said, it is not as if I take any enjoyment in that

At the very least I can shake off those thoughts of my mountain home that come

This four-sided, three and half-meter wide cage, is not really that small

In this dangerous world of ours, it is a miracle alone that this piece of Pure Land exists

We are not yet old

On the other side of the world, the orangutans confined in European zoos during the war fared little better than those in the Japanese territories. In the Bois de Vincennes Zoological Park in Paris, “a morose and dangerous orangutan” was one of the only animals that was shot instead of being taken away to safety. In November 1943, a bombing raid on Berlin Zoo allowed an orangutan known as Cleo to escape. Seizing her moment, Cleo climbed a tree and disappeared—only to be found, dead, in the city’s rubble a few days later.85 An elderly captive orangutan named Giulia reportedly survived in Rome right up until VE Day, when cigarettes flicked into her cage by celebrating Allied troops caused it to catch fire. Guilia was burned to death.86

The ‘Cold’ War

The end of the Pacific War did not bring peace to Borneo or Sumatra. Sukarno and Hatta promptly declared independence. In response, the Dutch directed their military to recapture by force their lost colonial holdings. As luck would have it, the Japanese (presumably with an eye to their own empire), had marshalled young Sumatrans into militias known as pemuda. In November 1945, with the Japanese departed, the pemuda organised into the Indonesian Socialist Youth (PESINDO) and defended Indonesia against a post-war alliance of Dutch, British, and Japanese troops (the Dutch and British had swiftly ‘forgiven’ the Japanese and even armed their soldiers), formed in order to confront the twin ‘evils’ of socialism and national liberation.87 Around 150,000 Indonesians (and 5,000 Dutch soldiers) were killed in the course of this conflict.

The United States had mixed feelings about these developments. In a memo from the time, William Walton Butterworth, the director of the US Office of Far Eastern Affairs summarised the United States’ goal as

the attainment of two objectives: (a) to contribute in every practicable way to a solution of the Indonesian problem; (b) to place itself in the best possible light with the Asiatic and Islamic countries… The [Dutch] resort to force has provided the Soviet Union with excellent propaganda…88

The US went as far as threatening the Dutch with the cessation of their Marshall Plan aid. This left the Dutch with little choice. With independence fighters showing no signs of giving up, the Netherlands formally recognised the Federal Republic of Indonesia in 1949.

The 1950s were a high point in the relationship between Sukarno and the PKI. Sukarno acknowledged the left’s contribution to the independence struggle, and they considered his bourgeois revolution against the old colonial powers to be a necessary precursor to the proletarian revolution. Even if this compromise was forced on both sides—with Sukarno compelled by the PKI’s rocketing membership numbers, and the PKI by Sukarno’s 1951 crackdown on labour unrest for the sake of ‘national security’—they shared a desire to nationalise and otherwise reduce foreign ownership of Indonesian assets.

Since the end of the fighting in 1949, the US companies Caltex and Bechtel had worked together to install “several thousand miles of road and pipeline across unmapped [Sumatran] jungle”.89 When the fervently anti-communist Colonel Simbolon began to agitate for the Sumatran region of Aceh to break away from Indonesia, launching violent attacks on the plantation workforce because of their apparent sympathy for communism, President Eisenhower authorised the CIA to “employ all feasible covert means” to support his efforts.90 Perhaps unsurprisingly, these CIA-backed secessionists allowed US companies such as Caltex to continue their operations during this time, so oil industry workers had an easier ride than the supposedly more pro-communist and pro-Sukarno plantation workers. The uninterrupted presence of Caltex and Bechtel in Sumatra in the decades to come was neither politically nor ecologically neutral. Leaked diplomatic cables from the 1970s show that multiple whistleblowers from Bechtel informed the US embassy that the company’s operations were contaminating the local water supply.

Logging on a divided island.

The Sukarno years saw a marked decrease in Sumatran timber exports, perhaps in part owing to the Basic Agrarian Law of 1960, which (at least partly thanks to pressure from the PKI) included a formal recognition of forest peoples’ traditional land rights.91 These policies extended, of course, into the Indonesian part of Borneo. Northern Borneo, however, continued under British colonial rule until 1963, when ‘British North Borneo’ and the former ‘Raj of Sarawak’ (which had become a British Crown Colony when the Brooke family ceded it in 1946) were ‘granted’ self-government and became the states of Sabah and Sarawak in the newly-formed nation of Malaysia. With logging in Sumatra now limited, the forests of Malaysian Borneo were forced to make up the shortfall.

Much of this logging continued to be undertaken by Japan. During its post-war occupation by the US, Japan was only allowed to import products that would be processed into exports for Western markets, or for direct use by US forces. This restriction caused Japan to import enormous quantities of tropical timber to process into construction-grade plywood. Throughout the 1950s, most of this tropical timber was either directly supplied to the US Army for use in the Korean War, or was exported for use in the Global North’s post-war housing boom. Figures show that at least 79% of the plywood exported from Japan during this period went to the West: 56% to the USA, 18% to Britain, and 5% to Canada.92 Almost all of this timber came either from the Philippines or Borneo. From 1959, when the Philippines banned further timber exports, pressure on Borneo’s forests intensified once again. In 1960 Japan imported 860,000 m3 of timber from Borneo, and exported more than 400,000 m3.93

Reconstruction at what cost?

As the historian William Steele has shown, Japan’s post-war reconstruction relied on the use of enormous amounts of cement. But cement is only as useful as the moulds that shape it, and so every square metre of surface cement required four square metres of plywood.94 After 1952, when the US ended its formal occupation of Japan, restrictions on Japanese imports were lifted. From that point, imported Bornean timber was crucial to the reconstruction process. This was because, as the Malaysian economist Jomo Kwame Sundaram has explained, “it costs less to cut down a tree and ship it to Japan”:

…workers in Japan earn far more than in Sarawak. But also the Sarawak rainforest is considered free; no compensation for the use of the land is factored into the cost of the tree. The government gives out the concessions instead of charging for them, and the forest people get nothing or a pittance.95

All of this was made possible with the help of a United Nations agency called the Food and Agricultural Organisation (FAO), which—conveniently for the Global North—advised both Malaysia and Indonesia to use their forests as engines for national growth.96 As Nancy Peluso and Peter Vandergeest describe, the FAO helped to establish the conception of forests as the sovereign territory of state forestry departments. Before the Second World War, this trend had been resisted by “the budding communist party, and the growing nationalist movements… [who] depicted foresters as land-expropriators”97—a view that was proved to be largely correct in the decades that followed.

Most of the timber extracted was sold to Japan’s sōgō shōsha (総合商社, ‘general trading companies’) conglomerates, which run at low profit margins whilst trading in exceptionally high volumes. This business model leads to rapid environment devastation and depletion—particularly when the ‘product’ being traded is timber. The post-war reconstructions and housing booms of the imperial core came at an unspeakable cost to Borneo.

“The Smiling General”

This logging frenzy reached Sumatra in 1965, when Sukarno was overthrown in a CIA-backed coup (their second attempt at such). Between 500,000 and one million people were murdered in the process, and tens of thousands of members of the plantation union SARBUPRI were killed by supporters of the coup.98 Even these crimes, perpetrated by reactionary groups in Indonesia, carry the stamp of British and US complicity—a fact established first through the diligent work of Indonesian historians, corroborated by research into Western national archives, and most recently expanded upon in English by the journalist Vincent Bevins, in his stark and impactful book The Jakarta Method.99

This cumulative work has confirmed that Britain’s Foreign Office ran propaganda campaigns to encourage the killers, planted fake documents on corpses and encouraged the targeting of ethnic Chinese workers,100 while US Embassy officers, the CIA, and the managers of US-owned plantations provided “kill lists” of union members to the Army.101

The slaughter began when the assassination of several generals by their military colleagues was blamed on the Communist Party. Anyone rumoured to possess even the faintest left-wing sympathy was held responsible for the assassinations, and thus placed, quite literally, in the firing line. The massacres also targeted (and destroyed) Gerwani, Indonesia’s nascent feminist movement. In the propaganda that circulated after the assassination of the generals, it was falsely claimed that before their deaths, they had been ‘sadistically tortured and humiliated’ by members of Gerwani, ‘their penises cut off and eyes gouged out as the women engaged in a mass orgy.’102 If this wasn’t a deliberate echo of the ‘castrating Red Woman’ archetype in German Freikorps literature, it certainly drew from the same fascistic wellspring.

Indeed, certain Nazi luminaries had longstanding interests in Indonesia. Hjalmar Schacht, former Reichsbank president and erstwhile Nazi minister, was as early as 1951 urging the new Republic to “overcome its reluctance to import foreign capital.”103 His 1966 book Magie des Geldes (translated in 1967 as The Magic of Money) featured a chapter entitled ‘Development Aid’, in which Schacht enthused that

Once its national aspirations have been satisfied, Indonesia will become one of the most flourishing countries on earth… it has almost limitless reserves of all raw materials.104

In 1964, Schacht sought funding to set up an oil palm plantation in Sumatra. Though his book records that this scheme “foundered on shoals of bureaucratic formalities”—his term for the global business community’s passé reluctance to be seen funding one of Nazi Germany’s most prominent figures—this disappointment was not to last. Sukarno had severed relations with the World Bank in 1965, but after the coup, this policy was swiftly reversed by Suharto’s ‘New Order’ government.105 A group of banks from Western nations with investments in Indonesia, called the Inter-Governmental Group on Indonesia (IGGI), was swiftly convened.106 The IGGI’s purpose was to coordinate each of its members’ investments in Suharto’s new Indonesia, to ensure that it ‘developed’ in a profitable manner.

According to the writer Horst Geerken, the IGGI decided that “a major bank from each country was to control the distribution of the funds”—and the bank selected to safeguard West Germany’s share of the wealth? None other than Bankhaus Ludwig & Co, which was once, under another name, a small institution best-known for having been founded by one Hjalmar Schacht.107

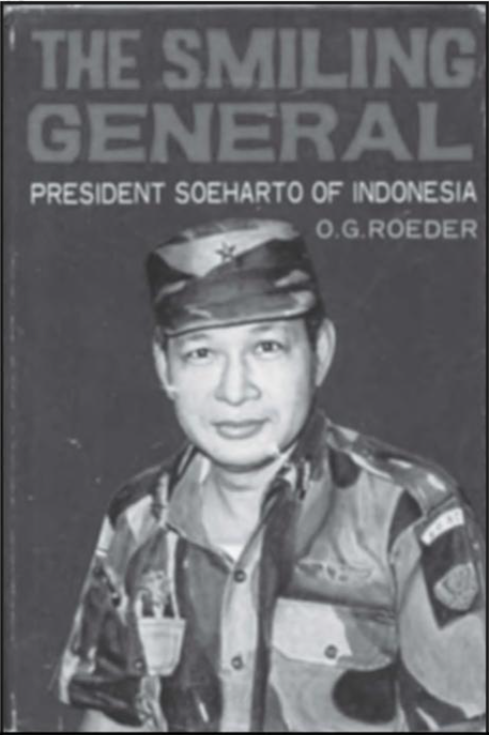

The Bundesnachrichtendienst (BND; the West German intelligence service) had also hired a Nazi as their man on the ground in Jakarta.108 Rudolf Oebsger-Röder, a former leader of an SD-Einsatzkommando who had been investigated for war crimes, supplied intelligence to the BND until at least 1966, operating under the name “OG Roeder”. In response to Oebsger-Röder’s reports, the West German ambassador to Indonesia complained in private correspondence that the “army continues its anti-communist cleansing campaign step by step with a slowness only comprehensible by Indonesian standards.”109 Despite this apparent disdain for the pace of the genocide, Oebsger-Röder became a close adviser to Suharto, and even published a gushing biography of the dictator, The Smiling General, in 1970.

‘The Right of Forest Exploitation’

The 1967 Forestry Law established the government in Jakarta’s sovereignty over all Indonesian forests, squashing the customary claims of the Indigenous peoples occupying 143 million hectares of resource-rich land. In the same year, the Foreign Investment Law introduced tax incentives to re-attract foreign business, which “in a few short years, controlled 59 percent of the capital in forestry products, 96 percent in mining, 35 percent in industry, almost 50 percent in hotels and tourism, and around 33 percent in agriculture and fisheries.”111

Suharto awarded control of concessions to his allies, who then got rich off granting logging rights to whichever company offered the most. The consent of local communities wasn’t sought or required, and the resulting land grabs were overseen by the military. Since all of this was done in the name of national development, the military were quick to accuse any protesters of being either unpatriotic or even—and far more dangerously—pro-communist.112 In Malaysian Borneo a parallel dynamic was established (and continues to this day), whereby, according to Lukas Straumann:

politicians in government hand out logging concessions to their favourites and, in return, pocket bribes, which they use to finance their electoral campaigns—as well as for private purposes.113

To expand the plantation sector, Suharto’s ‘New Order’ government then established ‘parastatal’ companies called PTPs (Perseroan Terbatas Perkebunan, or Plantation Limited Liability Companies), which operated mainly in Sumatra. The Ministry of Forestry promptly granted the ‘Right of Forest Exploitation’ to these government companies, as well as to private logging firms, most of which were run by Suharto’s political and military allies.114 Of the $1.34 billion that the World Bank lent to Indonesia between 1969 and 1974, $59 million went towards the government-owned plantations, and into the private bank accounts of these allies.115

It was during this era of environmental destruction that primatologists began to focus on the orangutans of Sumatra and Borneo.

Colonial primatology

Barbara Güttler had grown up in a wealthy Berlin family that lost its investments in Poland when the Red Army defeated the Wehrmacht. She worked for the Abwehr during the war, and then moved to Borneo. Once there, she met and married an Englishman, Tom Harrisson,—one of the founders of the British social research project Mass Observation.116 Harrisson had worked for the Department of Naval Intelligence, where he’d contrived to keep himself in a job by writing deliberately exaggerated reports of dockers’ communist sympathies.117 He ended up in Borneo after he was recruited by the Allied Special Operations Executive for Operation Semut, which intended to “save some of the face…lost to the Japanese” by parachuting into northern Borneo to rally the wartime resistance through guerrilla warfare. After the war, he took a job as the curator of the Sarawak State Museum; Barbara (then married to her first husband) was one of his staff. The pair quickly fell in love, and began to foster orphaned orangutans—with local women hired to act as their surrogate mothers.118

Another emergent figure in orangutan conservation was Ulrike von Mengden, who had been a nurse for the Wehrmacht on the Eastern Front and had narrowly escaped capture by the Red Army. In the 1950s, she moved to Java, where her husband had once been a plantation administrator. He took up a position as an advisor to the ambassador of West Germany, and Ulrike worked in an “overseas posted” position at the embassy.119

This was a crucial role. Archival research by Till Florian Tömmel has revealed that, throughout the Sukarno years, West German embassy staff were kept in a constant state of panic that Indonesia would recognise the East German socialist state as legitimate. As one of the most significant and influential non-aligned nations, Indonesia was seen as a ‘linchpin’ in the West German international ‘non-recognition’ campaign, and, prior to the coup, significant ‘aid’ donations had been paid in an attempt to buy Sukarno’s favour. For their part, the anti-communist faction of the Indonesian elite (which included both Suharto and the Governor of Jakarta, Ali Sadikin) had hoped that West Germany could become the Republic’s largest European trading partner, replacing the Netherlands.120 With the overthrow of Sukarno, the liquidation of the PKI, and the organised slaughter of every purported member of Indonesia’s organised left, the West German government and its overseas representatives were welcomed more warmly than ever before.

Ulrike von Mengden was, in her spare time, a frequent visitor to Jakarta zoo, and in 1966, the Governor of Jakarta invited her to run an orangutan rehabilitation centre within the grounds. Immersed in her rehabilitation work, she seems to have been insulated from the realities of the anti-communist massacres then sweeping Indonesia, but some of the political subtext seems to have coloured her memory of the period as “a political, dangerous time, a communist time.”121 Though she was undoubtedly a committed and talented advocate for the animals under her care, her status as a member of West Germany’s diplomatic community can only have endeared her to the Republic’s new anti-communist elite.

Western primatologists continued to flow into the islands. In 1968, the same year that von Mengden was given her rehabilitation centre, John MacKinnon—the nephew of British East Africa Company founder and inaugural colonial Governor of Kenya William MacKinnon—arrived in Malaysian Borneo to study the orangutans. Another leading primatologist, Herman D. Rijksen, was sponsored by the Dutch diplomat Jan H. Westerman, who “wanted to re-establish the wider nature conservation ties after the post-colonial turmoil of the Sukarno era”.122 We might note that this period of alleged ‘turmoil’ was identified as the era in which Dutch businesses were being nationalised by the new Indonesian Republic, rather than the subsequent period in which hundreds of thousands of people were slaughtered and vast swathes of forest were destroyed on an unprecedented scale. This, apparently, was a context in which the Dutch could do business.

For decades to come, they and others like them would be the ‘faces’ of orangutan conservation - the ones who seemed to supervise the animals’ protection and who starred in soulful cover shoots for the National Geographic, while the many Indonesian people who performed the ‘custodial labour’ - and who placed themselves at the most risk in confrontations with poachers and loggers - were kept in the shadows. And for all of their significant achievements, the many individual orangutans they nurtured and saved, and their profound contributions to our understanding of these animals, it’s undeniable that this was a primatology that arrived from and was imposed by the imperialist Global North. The scope of its ecology was narrowed, and if orangutans were even back then seen as an ‘umbrella species’, the violence served as a constant reminder of exactly how far to the left the umbrella would be permitted to open. The discipline of primatology was both enabled by and used to justify the capitalist rollback of decolonisation.

The palm oil era

Starting in 1979, the World Bank invested half a billion dollars in a scheme to further ‘develop’ the palm oil industry. Under this ‘Nucleus Estate’ scheme, smallholders would be given satellite plots of land surrounding a ‘nucleus’ estate and oil palm mill. The smallholders would be given a loan (much of which would come out of the World Bank’s substantial funding for the scheme), and in the meantime would work as wage labourers on the nucleus plantations. Once the plots were developed, the ‘nucleus’ estates were required to buy palm fruit bunches from the smallholders at a pre-agreed government rate, and the farmers were required to repay the government loan. The World Bank also funded further ‘transmigration’ schemes, so that millions of people from Java, Bali, and Madura in Borneo and Sumatra could be resettled to staff the plantations.123

When the worldwide price of crude oil collapsed in 1986, the New Order government scrambled to reduce its dependence on oil revenue, and increasingly relied on timber exports as a source of ‘foreign exchange’, i.e. US dollars.124 To further counteract the country’s previous dependence on crude oil revenue, the government also incentivised private companies to enter the plantation sector, for the first time since the colonial era, and produce palm oil for export. They offered these companies subsidised development loans and started a bonfire of red tape to speed up the process of granting permits.125 The palm oil industry’s ‘neoliberal’ era was underway.

Following World Bank pressure to reduce the subsidies given to smallholder farmers and increase access to private companies, the 1990s saw a major drive to convert forested land into oil palm plantations. By granting concessionary rates for plantation development, Indonesia now attracted large investments from overseas – particularly from Malaysia, where domestic plantation costs were increasing because of land scarcity and rising wages. By the time the Asian Financial Crisis hit, in 1995, Malaysian investors had acquired at least 1.3 million hectares. By 1997, the private estate sector was dominated by just eight conglomerates, one of which was the colonial-era company SOCFIN.

Financial crisis, financial opportunity

The Asian Financial Crisis caused mass unemployment and a collapse in the value of the Indonesian rupiah. The IMF insisted that Indonesia could liberalise its way through the crisis, and dictated that the barriers on foreign direct investment (FDI) in the oil palm industry must be lifted. The international price for crude palm oil remained high, and wages were suppressed as more people competed for jobs, so at first the crisis resulted in windfall profits for plantation companies. But as companies chased the profits that the crisis was enabling, increasing export sales by 59% in 1997, the supply of domestic cooking oil dwindled and domestic prices increased dramatically.

The situation was made worse by the El Niño Southern Oscillation, which caused severe droughts across Sumatra and Borneo. Plantation companies took advantage of the dry conditions to initiate forest fires to clear the land for new plantations, but the fires got out of hand and consumed an area the size of the Netherlands. People couldn’t afford to eat, and it wasn’t safe to work outdoors because of the choking smoke. Perhaps inevitably, unrest followed. Writing in 1999, Anne Casson observed:

Communities have stepped up protests against further oil palm expansion by burning estate offices, large machinery, processing plants and plantations… Looting [has] also increased..

To get a handle on the situation, the government was forced to ban exports altogether in 1998, but Suharto couldn’t survive the crisis, and in 1998, after 31 years, he was finally overthrown.

The orangutan conservationist Carel van Schaik has written about the “open season on natural resources” that followed the overthrow of Suharto.126 Schaik witnessed first-hand gangs of timber poachers felling trees in some of the last protected forests where orangutans still survived. But, although this undeniably caused destruction in precious habitats, Schaik felt that this timber poaching was “less destructive to the forest infrastructure [than normal commercial logging] in the long run because it does not damage the soil”.127 In the orangutan habitats of Sumatra, then, corporate business-as-usual was far more destructive than the anarchy of timber-poaching gangs.

The value of the Indonesian currency remained low in the early days of the post-Suharto ‘reformasi’ era. The IMF stepped in, ‘helpfully’ offering financial support, on the condition that the Indonesian government agreed to numerous reforms, including “abolishing its ban on foreign investments in oil palm plantations, liberalising trade in the agriculture sector, reducing export taxes on timber and minerals, and accelerating the privatisation of public enterprises.”128 The result of this intervention has been that, since Suharto’s fall, the land grabs have only accelerated. Though smallholders were granted 80% of the land in the original ‘nucleus’ schemes, they tend to be granted no more than 30% in recent equivalents, and most plantations are now in the hands of private companies.129

The World Bank has continued to invest billions of US dollars in schemes to lift restrictions on access to Indonesia’s resources by international capital, improving Indonesia’s position in the bank’s ‘Doing Business’ rankings in exchange for every liberalising measure enacted. Measures rewarded by the World Bank have included a 2010 policy to void people’s land rights if this was deemed “in public interest”.130 The resulting deforestation (around 117,000 hectares every year, between 1995 and 2015) wasn’t a side-effect of low-level timber poaching, but a direct result of IMF and World Bank pressure.

An interactive map of plantation expansion in Borneo over this time period has been developed by the team at CIFOR, and an equivalent map for Sumatra is apparently in the works. When we compare these maps to the WWF’s orangutan population map, a grim picture emerges.This expansion is most intense in the orangutans’ few remaining habitats.

Biofuel, wages and environmentalism

In late 2017, an article in the journal Current Biology announced that a new orangutan species—the Tapanuli orangutan—had been identified in Sumatra. It had been known since the 1990s that that the Bornean orangutan (Pongo pygmaeus) and the Sumatran orangutan (Pongo abelii) were distinct species, so formal confirmation that the Tapanuli orangutan was a third distinct species caused great excitement. But bad news soon followed good, as it emerged that fewer than 800 individuals remain, and those survivors are at threat from mining and infrastructure projects.