EDITION: ECOLOGIES.

The effects of flooding are determined by regional and by class inequalities. As the state withdraws its from crucial functions, this imposes tasks for the left that are currently under-analysed.

Perhaps one of the most interesting aspects of Bong Joon-Ho’s Parasite, beyond its explicit critique of modern capitalist social relations, is the storm which occurs in the later half of the movie. The Kim family succeed in gaining employment in the wealthy Park household, using different schemes to push out the previous staff. When the Parks go on a camping holiday, the Kims take the opportunity to revel in their employers’ empty home. Initially indulging in the luxury of the mansion, the Kims’ night of fun is disrupted first by a clash with the previous housekeeper and her husband, Moon-gwang and Geun-sae, and then the Park’s premature return home due to the stormy weather.

Quickly, the Kims must subdue both Moon-gwang and Geun-sae, clean the house, and ultimately sneak out from under the Parks’ noses – running home in the thundering rain. The weather is presented initially as merely disruptive; a gate camera shows the rain drenching Moon-gwang whilst she begs to come inside, the water is blamed for ending the Park’s holiday. Now, after some of the tensest scenes of the movie, water rushes into the centre stage in Parasite.

The Parks, once inside, are ambivalent towards the rain. Da-song, their son, decides to set up a tent in the garden, which his parents watch from their luxurious living room. The elder Parks rest on the sofa, flirting with each other as well as insulting the way Ki-taek, the Kim family father, smells. From the perspective of their concrete and glass vista, the rain remains a minor disruption; they are mainly keen for their child to come inside soon. In the words of cinematographer Hong Kyung-pyo – “the rain in this house, therefore, is so delicate that it’s almost romantic.” Water is a backdrop – an ambient soundtrack to the private moments of the ultra-wealthy.

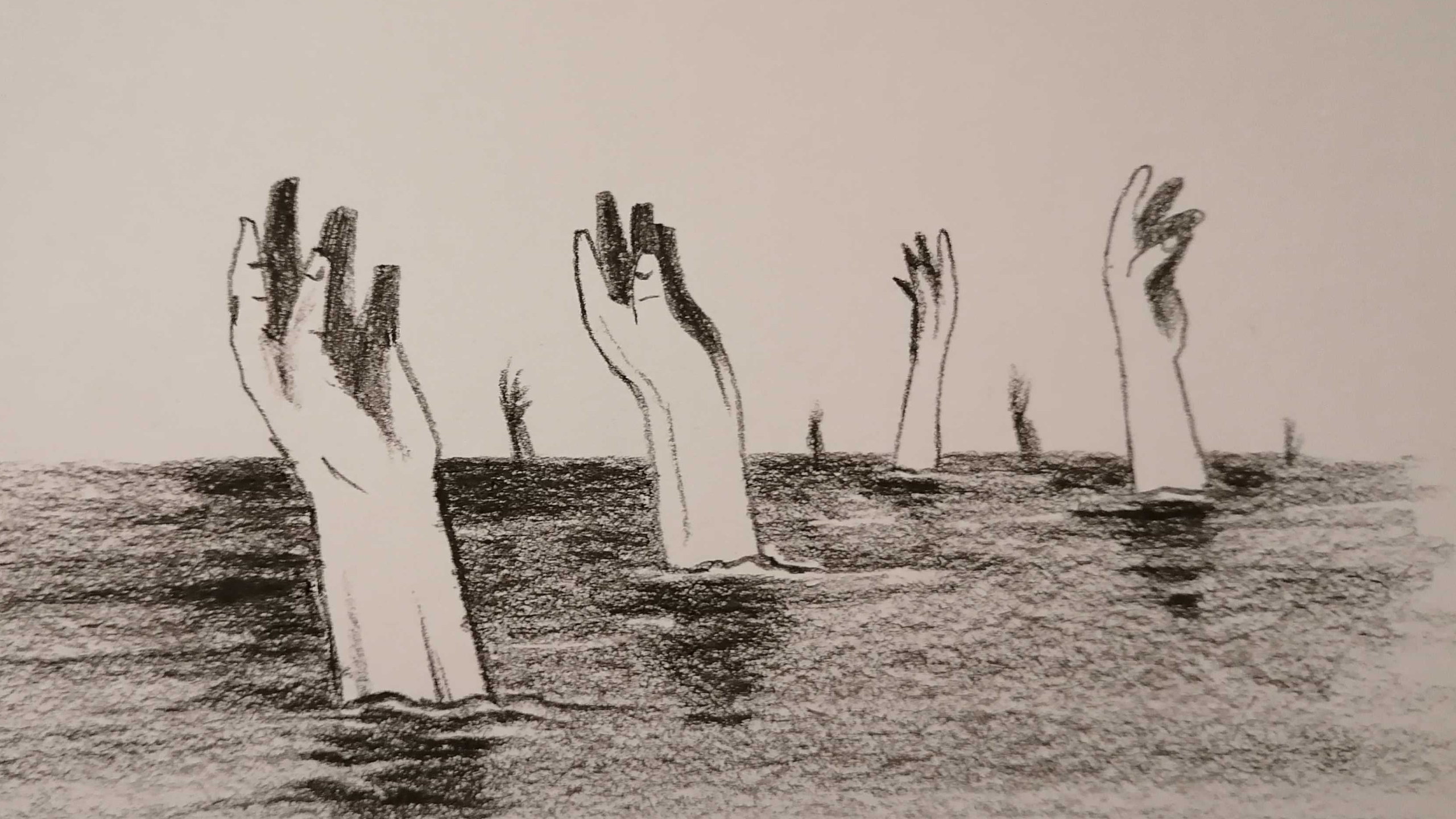

The Kims, running home in the rain, head down the hill to their basement flat, finding it flooded up to their chests. This banjiha is one of thousands of bunkers created in case of a hot war between North and South Korea and now converted into poor quality apartments. Their subterranean flat is now subaquatic. Neighbours are scrambling in the chest-high water in the street, and once inside the Kims find their possessions floating and sinking in the inundated basement. The family scramble to save their belongings and find themselves sleeping overnight in a nearby gymnasium with other displaced people.

What Parasite highlights in ways that few disaster films get right, is that events like flooding are experienced extremely differently by people even within walking distance of each other. To use Ruth Wilson Gilmore’s terminology, as it was recently mobilised by the Out of the Woods Collective, ecological crises are “group-differentiated.” Events like flooding deepen “the differentiation between who and what bears the brunt of disaster and who and what does not.”1 Respecting Stephen Graham’s calls to pay attention to verticality, the flood in Parasite differentiates from top to bottom. The Parks, whose home sits above the rest of their wealthy neighbours, feel the rain only slightly. Yet as we follow the Kims, and the water, down lower to their banjiha, it becomes a displacing and mighty flood, hurting those already exploited.

In this way, the flood in Parasite is a very on-the-nose representation of stratified class relations, with those at the top of the ladder being the wealthiest and those at its soggy base being screwed. To bring in another film, Parasite’s urban ecology is akin to Michael Gambon’s speech from Layer Cake; “you climb a little higher, you take less shit.” Taking on this vision of climbing, at the film’s end Ki-woo, the Kim family son, vows to one day earn enough to buy the Parks’ home. Here we have the individual who, despite everything they have seen and experienced, still believes they must strive to change their individual class position above all else. Ki-Woo’s wish is stripped of any collectivity - rather than rise with his class, he only can think of rising out of it. There is a hydrological reading of this final desire too; it is a scramble to higher ground as the waters rise.

What perhaps stands out most in this tale, is what comes the day after the flood, when the Kims wake up in the gymnasium. Despite their home along with those of many of their neighbours having been destroyed, they all attend a party at the Parks’ home as employees, each helping with different aspects of the day. Rather than many accounts of natural disasters, which leap from the event to the collapse of the social fabric, Parasite recognises that capitalist social relations continue even as disasters displace and disrupt. The Kims are still expected to facilitate the Parks’ wealthy follies, as their employment stipulates - come rain or shine.

Flooding on Normal Island

It is this latter point which brings us to Britain. For the last few decades, semi-annual flooding has become commonplace. Just last year, Britain faced the wettest February since records began, with flooding occurring in both England and Wales, with around 4800 homes and businesses damaged. This came hot on the heels of the November 2019 floods, which received intense coverage during the election, with areas of Yorkshire and the Midlands inundated, and Fishlake — a village near Doncaster evacuated. These recent floods join many which have marked this century; Winter 2015-2016, Winter 2013-2014, Summer 2007 and the many smaller events in-between.

As I finish the latest draft of this piece, in the dreary days of January 2021, Storm Christoph is wreaking havoc. Flooding is occurring at different points along rivers like the Severn, Derwent, and Mersey, caused by the recent combination of snow and rain. Wales has taken the brunt, with Skewen seeing 100 homes evacuated, after flood water burst out of an old mine shaft. With more weeks of rain due and river levels still high, the risk is not dissipating quickly. Whilst the flooding is, so far, not of the same scale as Winter 2019-2020, it is frustrating to see the same places scrambling to defend themselves from flooding. It does not have to be this way, with people chronically panicking that their homes will be inundated.

Whilst the causes of individual floods are always complex, from saturated ground to blocked watercourses, it is clear the recent rise in flooding is partially caused by climate change. In the words of the principal hydrologist of the UK Centre for Ecology and Hydrology Jamie Hannaford:

What we can say with some certainty is that there has been an increasing trend in flooding over the past four or five decades in parts of northern and western Britain, and this is consistent with what we expect in a warming world.

Given the almost certain intensification of climate change and its effects, the future does not look rosy. With expected increased rainfall in Northern Europe and rising sea levels, coastal, surface, and river flooding will all be serious issues for large parts of Britain by the middle of the century. The Committee on Climate Change, in their 2016 report on climate change risks, found that a 4C warmed world could see a massive rise in homes at risk from flooding – from 870,000 today, to 1.9 million by 2050. Worse still, Greenpeace’s investigative unit Unearthed recently discovered that thousands of “high consequence” flood defences in England were officially classed in “poor condition”. Many of these crucial defences were managed by third parties who the Environment Agency has little capability to compel to act, leaving flood protection up to creaking and damaged equipment.

Unless urgent action is taken, Britain will see thousands displaced, living in damp conditions, and otherwise precarious, as waters constantly threaten to inundate. Whilst the struggle to mitigate emissions and avert climate change’s effects must remain central there is the additional difficulty of tackling climate change’s current impacts. These bring their own ecological politics which the left cannot ignore. The unfolding flood crisis in Britain is only one amongst many climate change impacts occurring worldwide, for which there is little preparation or resources. Climate colonialism has meant not only is Britain refusing to pay its climate debt and fill the loss and damage gap in the Global South, but it has also neglected adaptation in its own territory.

Despite both the current harm caused by flooding and its almost certain exacerbation in years to come, the regular existence of flooding within Britain is more or less taken for granted by the state and media. Given the hundreds of thousands living on current floodplains, and the many more people expected to be at risk in the coming years, the refusal to contend with the reality of climate change is terrifying in its violence. Just like the Kims, going into work despite their inundated home, people across Britain are expected to continue working for a system which causes their drenching. The engine of global climate breakdown that is Britain, through its offshoring of emissions, extraction of minerals, and its continued funding of ecological destruction, is expected to keep rolling irrespective of floods. Worse than this, the floods themselves reinforce the inequalities capitalism produces.

Regional Inequality

It would be poetic justice if those at risk of flooding in Britain were the capitalists who have fuelled planetary breakdown. However, as with nearly every aspect of environmental destruction, the impacts fall unequally towards the exploited. If the flooding of Parasite is a vertical inequality, with impacts falling most on the banjiha and least on the hilltop mansions, flooding in Britain falls across its own strange regional divides. The following analysis is primarily focused on regional inequality in England, given the devolved management of flood risk, Scotland, Wales and the North of Ireland deserve their own account of how the British state has left them bailing water out of homes.

During the November 2019 floods, Jeremy Corbyn visited flood victims and claimed that spending on flood defences until 2021 was heavily skewed towards the South East, invoking a North/South divide for flooding. This claim was heavily questioned by fact checking agencies, not least of all because data on historic spending on flood defences was removed from the DEFRA site. Moreover, the evidence that did point to an inequality was explained away on the basis that London and the South East’s spending was higher due to the various projects on the Thames Estuary planned to last decades. Once these flood defences were removed, Yorkshire and Humber came out as receiving the most funding.

This, as well as being a feat of mathematical gymnastics, is not much of a defence of the justice of spending on flood defences. Indeed, what was shown by the fact that spending on the Thames Estuary extended beyond 2021, was that the Thames, and with it the centre of capital accumulation and extraction — the processes leading to planetary climate breakdown — gets planned, decades-long flood defence projects, whilst the Humber gets stop-gap solutions.

The reality is that flood defences are being mobilised unevenly across England, with many significant recent flood events hitting areas like Yorkshire, the North West and the Midlands. To build on Tom Hazeldine’s excellent work The Northern Question recent history is not only a question of the North’s economic decline but also escalating ecological inequality between North and South. Even then, regular flooding continues to impact areas like Oxfordshire and Somerset showing the difficulty of a hard binary between North and South. Much of these inequalities are produced due to government focus on protecting areas useful for capital, the centres of large cities like London, neglecting the many other settlements at flood risk — a crude case of town versus country. Of course, these inequalities are not only within England, the intensity of flooding and its effects in Wales as well as the lack of resources for flood defences is particularly notable on a British level, and made even more complex by flood risk management being devolved. On the one hand then, Wales does not get the resources it needs from Westminster, on the other the distribution of these resources within Wales is unjust and devolution allows everyone to pass the buck.

Even if the regional inequalities around flooding are acknowledged, there remains a risk that this gets read through the simplistic, rhetoric of monolithic “red wall” contrasted with “metropolitan elite”. The mythic image of homogenous deprived communities being inundated never fits flooding; it is always more complex. Not only is the stereotype of a monolithic ‘red wall’ a patronising generalisation, it also robs us of the capacity to describe the complex ways in which flooding impacts residents of these regions. Contrary to a wave hitting a passive deprived community, serious thinking about flooding requires a recognition that inequalities operate within regions like Yorkshire and the different ways that agency is constrained by class is crucial to reinforcing capitalist relations. A flood may hit a particular place that is resourced in particular ways to protect it (or not) from flooding but, as in Parasite, the impacts of flooding will be overdetermined by class.

Important here is the fact that one of the major responses to flooding in England is the support the government gives to ‘property resilience.’ The measures that come under this concept are varied, but what they constitute is adjustments made to buildings aimed at preventing water getting in and if it does so, ensuring that damage is minimised. In the aftermath of floods, homes can receive Property Flood Resilience Grants from local authorities of around £5000, in the hope that this will better prepare them for future flooding. The problem for many households is quite simple; the cost of maximising their home’s defences through all possible changes likely far outstrips this small amount.

In the long run the effect is simple. For those wealthier flood-impacted residents, who can afford extensive insurance and have reserves of money, it is possible to install the maximum potential changes to the home. For many others, affording even basic repairs is difficult, particularly for those uninsured. An instructive document which illustrates this is the Property Flood Resilience 2020 Update, an 86-page booklet which goes through the different measures adopted by a wide-variety of properties. Here we see households which excavate their entire bottom floor, install pumps and generators, or replace kitchens with raised wooden furniture. At this point the £5000 from local government becomes a useful bonus, maybe for buying a few flood doors, for example. All of this is predicated both being the owner of your home — despite renters still being at risk of having their possessions destroyed in a flood — and having enough money and time to plan these projects. Just a cursory glance across these case studies will see several large country houses from across England, suggesting that the model ‘resilient’ home is also a wealthy one.

Any account of British flooding requires recognition of these local landowners and capitalists within flooded regions. With many able to adjust reasonably to flooding, whilst others are stuck chronically scrambling to repair their homes, what emerges is the need for an understanding of floods in Britain as entrenching inequalities through this particular mobilisation of resilience. Under the austerity policies of recent years, government spending on flood defence infrastructure has fallen. At the same time, by pushing responsibility to prepare for floods onto the household level, flooding adaptation policy creates a diverging class relationship between those able to recover quickly and those forced to live in chronically damp conditions. These developments in flooding policy, dripping in resilience discourse, place the onus on being prepared for flooding on households, ignoring fundamentally that there is a differentiated capacity to cope already baked into modern capitalism.

To use the Out of the Woods collective’s terminology again, flooding impacts are group-differentiated on two levels – across Britain’s regional inequalities and between different classes within the flooded regions. Such a situation requires an urgent strategy from the left which can confront these realities in an increasingly inundated island.

Adaptation to The Tides

For several decades, the environmental movement has talked of ‘mitigation not adaptation.’ Implicit within this is an understanding that adaptation is being mobilised by a class which refuses to accept rapid emissions reduction. Such reductions in greenhouse gases would avoid wider global immiseration but would require a change in the relations of production. Now, ‘mitigation not adaptation’ should remain fundamental to a truly internationalist working class led environmental movement, with the impacts of both continued extraction and climate change itself set to most impact those in the Global Majority. However, what the current management of English flooding shows is the continued necessity of organising around adaptation as well – mitigation must remain primary, but the field of adaptation cannot be neglected.

Recent scholarship, such as Holly Jean-Buck’s After Geoengineering, has attempted to argue for a socialist response to geoengineering technologies as necessary to adapt to and mitigate climate change. Recognising the necessity of these technologies may be only half the battle. As Justin Reynolds says, ‘ecosocialists need to evolve strategies for using them wisely’. However, issues like flooding, and the insufficient response thus far, points to the need for attention to the technologies of climate change adaptation which seem to emerge on a less spectacular scale than geoengineering. The conversations around geoengineering, which often lack serious discussion of how progressive forces are to gain control of such technologies, nevermind what a positive use of them might look like, or even how far the technologies themselves are shaped by capitalism and imperialism, mask an even more urgent struggle around the existing technologies of adaptation. Many are looking to the skies, ignoring the water pooling at our feet. Whilst the focus on household change here in Britain is less exciting than atmospheric dimming, these responses must be contested as well.

What is needed is a form of socialist politics that can intervene in these flooded spaces to advance the struggle against climate breakdown. We see glimpses of this in several projects invoking communism. Out of the Woods speak of disaster communism, the Salvage editorial team speaks of salvage communism, and Malm has recently pushed for a reinvigoration of the notion of war communism. Whilst there are vast differences between these conceptions, all of them invoke a politics of people coming together to struggle under conditions of great strife. Such a politics chimes well with the situation here in Britain and worldwide - socialists know that flooding events are coming, and we even know many of the areas where it will likely occur. This rough and ready knowledge of flood risk poses a question - how best to organise so that we are ready as the floodwaters rise?

To return to Parasite, is the strategy for climate adaptation perhaps that of Ki-taek, who takes the opportunity to kill the Park family patriarch, then in the ensuing chaos retreats into the bunker underneath the Park home? In the coming crises that climate change might bring, might not the working class take the opportunity to seize the ruling classes’ bunkers for themselves? Such a strategy is deeply risky. It assumes that the ruling class will create spaces secure from climate crises, that they will be of sufficient scale for the working class, and most importantly, there will be an opportunity for the working class to strike and seize. Too much contingency. The crises that flooding brings and the potential to organise at the brink of disaster requires more serious planning from socialist movements.

At the same time, there is an extensive exploration to be made of the politics of mutual aid in the recovery from flooding. There is a temptation, and a practice for many, to fall back on the romantic notion of the “community” coming together to support each other during floods. Just as nascent mutual aid groups in response to coronavirus have had to fight against co-option from the forces of the state and capital, emergent community forums which tackle expected flooding face the same risks. However, even if they were not co-opted, the expectation that residents, many of which may have already been flooded several times, will have the capacity to come together to defend themselves is dubious. Such organising is always rearguard and strained for resources and time. Even then, given the variety of class interests potentially affected by flooding, there is the difficulty of ensuring such spaces link localised flooding to the politics of capitalism and climate change. As the state retreats from seriously funding flood defences and the obligation is put on households, to place the organisational burden solely on emergent forms of community mutual aid from those living in and around flooded areas dampens organisational potential. With people across Britain struggling already with the gutting of social services and worsening living conditions, why should it be their responsibility to also mount the defence against flooding?

The efforts to organise against floods in Britain is doubly complicated by the fact that flooding often occurs in the very communities which ‘grassroots’ forms of organising have receded from. Often rural villages are most affected or sprawl outside of large ex-industrial towns, as in November 2019 when Fishlake and Bentley were some of the most impacted communities. The slow fade away of spaces where traditionally left-wing projects could gain a foothold – working men’s clubs, community centres, etc. – combined with the absence of a surplus of organisers with capacity, as is often the case with cities, presents a further practical challenge both in terms of the possible effectiveness of efforts from below and of the possibilities of its politicisation to the left.

What is needed is socialist movement which makes itself known to people at risk of flooding, through both organising in the recovery period and through constant agitation around the link between government negligence, capitalism, climate change and flooding. Such a movement should attempt to link the various floods which are occurring across Britain and the world together, to understand that there is nothing ultimately natural about these disasters. Such a network requires both those embedded within at-risk communities and those outside who can rapidly organise in solidarity. At the same time it requires the organisation of resources from those on the left to be mobilised, whether it is solidarity funds or a dinghy with the red flag.

Conclusion

When, on the southern slopes of the mountains, the Italians of the Alps used up the pine forests so carefully cherished on the northern slopes, they had no inkling that by doing so they were cutting at the roots of the dairy industry in their region; they had still less inkling that they were thereby depriving their mountain springs of water for the greater part of the year, with the effect that these would be able to pour still more furious flood torrents on the plains during the rainy seasons.

With the recent marking of 200 years since Engels’ birth, there has been an emergent attention paid to his writings on ecology. The above quotation from Dialectics of Nature is striking, with its implicit message about the limits to “man’s” “mastery” of nature2, but also because of the difference implied between Italians felling the Alpine forests and today’s climate crisis. Put bluntly, we have the inkling that the continued growth of the capitalist mode of production will lead to further flooding — we have some understanding of both the symptom and cause of planetary breakdown.

To return again to Parasite’s flood and to Ki-woo’s desire to ultimately purchase the home his father hides in, what is needed is a strategy that rejects the capitalist route to higher ground and points to other ways of securing dry ground than buying a higher home. A strategy that looks to the many flood victims in the gymnasium, and the wider world - which understands the flooded working class as the global majority, and as therefore capable of seizing and creating spaces like the Parks’ home together.

Here in Britain, we know disaster is around the corner, we know the response will be inadequate, and we likely know the kinds of places it will occur. Let us take this inkling and spin it into a strategy for a flooded island in a warming world.

Afterword - Summer 2021

While this edition was being prepared, a Europe-wide heatwave broke, with heavy rain showers leading to flash flooding occurring in several locations. The storms hit heaviest in Western Germany and Belgium, where hundreds died and thousands were left unhoused and in dangerous conditions. Furthermore, London saw several flash floods, particularly in East London, with Pudding Mill Lane station coming to resemble the marshlands Stratford sits uneasily on top of. In addition to the above essay, these latest rounds of flooding concretise three things I’d like to highlight with regard to an ecosocialist approach to flooding.

Flooding as a housing issue. Obviously when people are displaced by floodwaters, flooding is a housing issue. However, the flooding in London makes clear that flooding works to compound already existing housing issues in several other ways.

Tenants, already in damp spaces due to the poor quality of London housing from years of landlordism, found themselves dealing with water rushing through ceilings and pooling up from the floors. Basement spaces in many London properties found themselves quickly filled, then emptied, leaving damage and despair behind. In one sense, flooding is an extreme end of a scale of moisture, with many tenants forced to live in damp, humid, and otherwise unsuitable conditions due to liquid housing.

The London floods were notable for their concentration around Olympic Park in Stratford, an area currently targeted by several property development schemes slowly chewing into the terraced housing to the East and West. Thus gentrification, the systematic and racialised pushing out of the working class from East London, intersected with flooding. Pudding Hill Lane Station was engulfed, showing not only the poor capacity of this new infrastructure to respond to flooding, but that the Olympic Park itself is potentially badly designed to respond to rapid rainfall. This eyesore region of the halcyon 2012 Olympics, is a sore eating into the surrounding areas, both with regard to housing and flooding.

On the other hand, the way flooding is mediated through housing suggests a crucial bedrock for organising the movement I’ve indicated above on the British left, namely the return of groups like London Renters Union, ACORN, and Living Rent, who are organising tenants in many of the areas flooded. The potential alliances between the movements against landlordism and climate change’s effects are underexplored today, but there is space for a liberatory alliance which could lead to a qualitative shift in organising around flooding.

The far-right increasingly understand this problem too. In Germany, it became clear that many elements within the country’s resurgent far-right were being encouraged to participate in the flood cleanup.

Flooding, if sufficiently large scale, can act to remove the legitimacy of many institutions within the state apparatus. This is in part why British floods regularly see the Prime Minister, Prince Charles, and others rush up to participate in the recovery. The point is not to fix the issues locals face, but to be seen as participating or concerned about the issue. By rushing up, an act of little utility to someone facing flooding, an ideological function if fulfilled, an attempt to shore up the legitimacy of the state in the face of crisis.

Just as the left can recognise this collapse of faith in the state, mobilising to articulate a different kind of politics in the recovery period, so too can the right. Thus, climate events are quickly becoming a tension point, a moment of confrontation between fascists and anti-fascists on the left. The latter have been slow to the draw.

This is fixable. At the same time as these floods were occurring, Summer 2021 also saw the publication of the latest Climate Risk Assessment from the Committee on Climate Change. Whilst it makes for stark reading, there is one element of this report which deserves quoting:

The UK has the capacity and the resources to respond effectively to these risks, yet it has not done so.

The point is not the inability of British society to respond adequately to climate change risks, but its refusal to do so. Rather than hide behind images of doom, these risks must be cooly faced with a scientific eye and a desire to free ourselves from climate colonialism and racial capitalism.

-

Out of the Woods Collective. 2020. Hope Against Hope: Writings on Ecological Crisis. Brooklyn: Common Notions. p. 6. Ruth Wilson Gilmore. 2007. Golden Gulag: Prisons, Surplus, Crisis and Opposition in Globalizing California. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 28. ↩

-

And see also Raymond Williams on the question of “mastery of nature” in Engels: “Engels went along with that and then suddenly remembered where the metaphor came from and said, quite correctly: we shall never understand this if we fail to remember that we are ourselves part of nature, and that what is involved in this mastery and conquest is going to have its effects on us; we can’t just arrive and depart as a foreign conqueror. But even then he shifted back, under the influence of this very strong nineteenth-century triumphalism about nature, and took up the metaphors again.” ↩