EDITION: ECOLOGIES.

In a contemporary "expansionist" Marxism, luxury plays a central role, but it also remains underthought—particularly in its ecological implications. The "severe luxury" of William Morris has much to teach us.

Of all the components of the eponymous slogan of Aaron Bastani’s Fully Automated Luxury Communism: A Manifesto, it’s “luxury” that receives, oddly, the least attention. In the conjunctural argument Bastani makes, each element of FALC as a leftist political orientation in the present is interdependent. Communism must be fully automated because, he claims, it was “impossible” before the 21st-century technologies of AI, gene editing, cheap renewable energy and so on threatened to do away with the calculus of resource allocation altogether. And yet, the inflection of “luxury” lacks the positive content foregrounded elsewhere in Bastani’s argument. Its definition has a curious circularity. He invokes Marx’s description, in Volume III of Capital, of the “realm of necessity”: “[j]ust as the savage must wrestle with nature to satisfy his needs, to maintain and reproduce his life, so must civilized man, and he must do so in all forms of society and under all possible modes of production.”1 For Marx, the “realm of freedom” only begins where social production is no longer dominated by this compulsion, a threshold to which the increasing quantity of surplus labour in the production process points, as capitalism “creates the material means and the nucleus of relations that permit this surplus labour to be combined, in a higher form of society, with a greater reduction of the overall time devoted to material labour.”2

Yet at the same time, despite luxury’s lack of content, it bears an enormous amount of responsibility. In the erratic motion of Bastani’s argument it is what necessitates embracing automation and concurrent technological shifts. How would, amongst other material provision, universal basic services, easily available non-animal meats and extensive, green public transit be viable without genetic modification and asteroid mining for rare earth metals, in a world where the working week has been massively reduced and “labour and leisure blend into one another”?3 Bastani characterises the extension of mining beyond the Earth sphere as an influx of “natural abundance” that FALC will happily incorporate, and lab-grown meat, in a repetition and extension of the advent of agriculture, as an example of humanity’s “unique ability to reprogramme the gifts of nature”.4 If, as Jason Moore has suggested, “what we are seeing today is the ‘end of cheap nature’ as a civilisational strategy”5, one premised on the armed maldistribution of access to natural resources that is the substance of imperialism, this further global shift presents a plausible, if magical, solution to a problem that ecosocialists and anarcho-primitivists alike have (often against their own emphases) indicated: namely, the political and social organisation of nature as raw materials in production. Luxury resolves the contradiction between ecological crisis and the organisation of society as abundance, but it does no more than this.

This is all the more puzzling in that the concept of luxury has, across its history, been the repository of specific and heavily freighted social meanings. The term first came into use during the medieval period to distinguish highly worked illuminated manuscripts from texts for everyday use – from the Latin lux or “light”, it referred to their decoration and gold leaf. It was an order of material culture set apart from simple use, whose ornamentation, workmanship and materials, precisely because scarce, impractical or fragile, indexed a different kind of value. Crown jewels, gem-studded reliquaries and gilded picture frames gave body to the pre-capitalist hierarchical system of court, church and feudal loyalty. Such archaic values persisted under capitalist modernity, but now in the form of the abstract social domination of dead labour. In the apparently modern forms of use value and exchange value, luxury gained a strange and increasingly horrifying afterlife, social stratification taking on a new and specific form in the market. But in this same movement, the new universality of exchange robbed it of its traditional basis. Material distinction, as Theodor Adorno wrote in 1945, was now the effect of a production process that “artfully equips” some goods with worse and better craft, “without anything being altered in the basic pattern of the mass-produced article”6. Displaced into modern class society, luxury was thus riven beneath the surface of its pristine unity by the contradictions of capitalist social production in general, its tendency towards universalisation - anyone with the cash could buy what had been the preserve of aristocracy - curbed at every moment by the deprivation that the wage system necessitated.

It was for this reason that luxury was the object of an extraordinary set of discourses in the 19th century, at the hands of both bourgeois moral education and the nascent socialist movement: moral panics, vituperation, fetishism, utopian images of general superfluity that extended from the lemonade seas of Charles Fourier to the immovable jewelled tortoises of JK Huysmans. The distinction between luxury and cheaper utility goods wasn’t reducible to a difference in use value – never isolable in any case – nor to increased inputs of labour-power that might increase its exchange value, separate as the latter is from its market price in Marx’s analysis. Rather, luxury became in some sense a social figure for surplus value itself. In economics, a luxury good is technically one “whose consumption at any given price rises more than in proportion to an increase in income”. During the high period of monopoly, when capital concentration, time-space compression and a increasing organic composition of capital accrued growing surplus value to capital, luxury came into its own as a signifier of the lifeworld of the business-owning class and its retainers in the upper-middle classes. Thorstein Veblen, writing in the 1890s, identified the “conspicuous consumption” of the non-labouring classes as an externalisation of surplus value. The vast difference between the salaries and windfalls of the “leisure class” and what each member needed for their social reproduction was written as a mark of “differentiation” in cars, furnishings, travel, food and so on.7 Prior to the Depression, a whole industry and design ethos sprang into being devoted to supplying these pseudo-needs, in a synecdoche of capital’s autonomous and cyclical self-generation. Luxury was in this sense the sign of the holders of capital as a self-conscious class-in-itself, that had made obsolete that curious vehicle of its genesis, the bourgeoisie or “middle class”. Surplus value expended in conspicuous consumption was effectively lost to capital in its guise as productive enterprise or commerce. It was a contradiction of capitalist production making itself felt in bourgeois thought, between the supposed ends of capital accumulation and the horrifying actuality of its end-less being. In the social polemics of the Gilded Age in the US, as the social and environmental consequences of rapid industrialisation became clear, luxury was entwined with waste – Veblen described the rich as compulsively frittering away their disposable income, displaying thus the fact that they could – and opposed to use, the needful, a utility applied to the claims of Marx’s “realm of necessity”.

In other words, if “luxury” is a concept with only a partial and obscure relationship with Marxism, it’s certainly one with a long history in modern social criticism. What, then, does it mean for a Marxist critique and overcoming of the existing economic system? Does a socialism worth achieving mean caviar, Hermès and Hispano-Suizas for all? It’s reasonable to ask – as I intend to do in what follows – what this troublesome concept, premised on the eternal swelling of surplus value, the spread of production and its waste in circulation, can mean for socialism – what values it can embody when extracted from the unfreedom of class society. In particular, I would like to ask whether the provocation of Bastani and associated ideologues of material abundance can shed light on the methods and ends of a socialist politics that takes its social imbrication in nature – as the meeting of need and the disavowed foundation of the realm of freedom – seriously.

Luxury, Need, Nature

To ask “why luxury?” provokes some obvious answers for socialists. Bastani and associated theorists such as Alex Williams and Nick Srnicek – advocates of what I will call an “expansionist” position – point out how thoroughly neoliberalism has failed in its ideological promises of expanded access to wealth and greater individual freedom. Even before the coronavirus pandemic, a decade of austerity following 30 years of stagnant real wages left large segments of workers in the advanced capital countries on the edge of poverty. Many more have slipped through a threadbare social safety net into even deeper privation. Going without is an everyday reality even for many who won the jobs lottery. The collective appropriation and redistribution of social wealth would allow a glamorous alternative to this increasingly dun and depressive reality. The sheer venom with which the British press attacked Labour’s 2019 manifesto promises – which would have amounted to only a modest increase in the social wage compared with the remaining European social democracies – show how indefensible, even within the ideological matrix of neoliberalism, current patterns of material provision really are.

But why is it that this critique is presented in a specifically Marxist framework, a version of what GA Cohen called “the fettering thesis” of the transition to socialism? If everyday material abundance is your goal, neo-Keynesian stimulus programs could get you there – some versions of a proposed Green New Deal certainly inhabit that territory. Such a social democratic luxury - which wouldn’t, in the vision of critics like Alyssa Battistoni, be all that luxurious, but a form of updated municipal gas-and-water socialism - would at least posit, beyond the benefit to everyday life, a break with the negative freedom of neoliberalism. And despite their ongoing reliance on current imperialist patterns of resource extraction, such provision would no doubt have a role in constructing the populist blocs that Srnicek and Williams deem necessary.

The answer, from one angle, is that the freedoms of a well-funded state capitalism remain abstract: luxury doesn’t do away with alienation and the wage relation. And yet, as we’ve seen, in the same movement luxury loses its content. As the expansionists all point out, freedom is nothing without its material underpinnings – without, as Williams and Srnicek put it, “maximal provision of the basic resources needed for a meaningful life: things like income, time, health and education”8 – and luxury is the expansion of that provision beyond the needs of mere social reproduction, without a corresponding increase in compelled labour. Marx is clear that freedom must rest on ongoing labour, but does not admit of this compulsory satisfaction of need: “[t]he realm of freedom really begins only where labour determined by necessity and external expediency ends; it lies by its very nature beyond the sphere of material production proper.”9 The expansion of surplus-value – the very body and substance of “luxury” under capitalist social relations — is, Marx reiterates, the condition of possibility of a properly free society where “socialized man, the associated producers, govern the human metabolism with nature in a rational way, bringing it under their collective control instead of being dominated by it as a blind power”.10 In this sense, for the expansionists “luxury” as surplus value forms the “Northwest Passage”, the reversible connection, that in its contradictory unfolding links present unfreedom and future freedom. It is thus the dialectical element of an otherwise frequently non-dialectical theory of systemic and political crisis. But this requires a further step that Marx warns against, from the rational control of nature through automated labour to freedom itself.

Thus, if there is little content to expansionist luxury, it is because it consistently collapses together freedom and its material infrastructure, filtering out the social contradictions and shadows of waste that, in the capitalist configuration of production relations that they take as their starting point, give “luxury” its richness and texture. This collapse also takes place temporally, flattening together the small pockets of freedom of everyday life in the contemporary Global North — consumer choice over cereal brands or social media, at least past a certain income threshold — with their foundation in spatial patterns of uneven development in the Global South, and their redemption and qualitative transformation in a universally free society.

Even more curiously, this conception of luxury has little to do with the — somewhat marginal — place of “luxury” in Marx’s own account. His remarks on the category of luxury goods in the Grundrisse and the second volume of Capital mostly concur with the sociological definitions we’ve already seen. Both the “necessary means of subsistence” and luxury goods, which “enter the consumption only of the capitalist class, i.e. can be exchanged only for the expenditure of surplus-value, which does not accrue to the workers”, are necessary to the upholding of the circulation of capital.11 Luxury “is the opposite of the naturally necessary” as it presents itself in the alienated second nature of the market.12 For Marx, the “necessary needs” or “necessary means of subsistence” of the working class are the subject of class struggle; “there enters into the determination of the value of labour power” - the swelling or shrinking of what are classed as “necessary needs”, as bought by wages - “a moral and historical element”.13 From one perspective, then, the expansionist position simply sees the contemporary class struggle as one extending what are currently considered “luxury goods” to the whole working class, as a guaranteed basic provision, as the contradictory tendencies of an exhausted industrial capital make goods increasingly accessible, in opposition to big tech’s tendency towards monopoly. In this sense, it reiterates a reformist case that recurs throughout the history of socialism and social democracy, around wages and conditions as access to the goods of accumulation, a case that recurred at the heart of the Sanders and Corbyn campaigns. To take this case as the basis of a vision of a future society beyond the reforms that capital is now increasingly incapable of making, however, is a different and more puzzling proposition. As Agnes Heller notes, “luxury” as a category of need or compelled necessity would lose its meaning in a communist society, “not only because the so-called ‘luxury needs’ cease to exist, but also because the system of ‘necessary needs’ itself changes, opening the way for the development of individual ‘free needs’”.14 In vulgar terms, “luxury communism” is thus a self-contradictory phrase. But more importantly, this shift, by which quantity turns into qualitative transformation - the abolition of alienated private property as an image of blind and immutable nature — and the meaning of luxury in its unfreedom is dialectically transformed into the new and unprecedented meaning of human freedom, is nowhere to be found in the expansionist account.

If the expansionist account ultimately breaks with the Marxist framework it claims to base itself in, from what does its “luxury” derive its meaning? One obvious source is its remarkably elastic conception of ‘need’. Socialism is often characterised as a restructuring of social production to meet the needs of the majority responsible for production itself – recall the early Soviet slogan of “peace, land and bread”. Yet need becomes a stick with which to beat socialist demands. As Mark Fisher notes, when professional dimwit Louise Mensch lamented of Occupy London “not only that the occupiers bought corporate coffee – they also used iPhones”, the implication was that the demand to meet need requires scourging and repressing desire.15 This assumption is often repeated on the left, in degrowth and democratic socialist circles alike, in the static form of debates about whether a socialist society would continue to have Apple Watches, Prada, air travel, etc. The expansionist account refuses this opposition of need and desire. Fisher, for his part, suggests that a post-capitalist society would incubate new desires that the paltry luxuries of neoliberalism embody in “degraded” form, a claim that recalls the utopias of the Situationists, who envisioned a society of automation in which survival would give way to perpetual “adventure” amid the luxuries of a ruined imperialism. Need and desire remain distinct, but desire leads free subjectivity to the repeated expansion of its own conditions of possibility in the process of psychedelic “consciousness-raising”, as Fisher suggested in a later essay.16

Bastani and Williams/Srnicek go further in one direction than Fisher, though the confusion of categories that we’ve seen in their work leads to some muddle in this regard too. If luxury is the useless – the aggregate wealth that isn’t directed towards the mere end of social reproduction – then the automation of labour removes the question of need entirely and makes everything luxurious: as an Atlantic article on Bastani’s book put it, it sees not just “the bottom of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs forever lopped off” but “a life in which virtually all of your needs were met” without compulsory labour. Likewise, Williams and Srnicek frame their project in terms of a “synthetic freedom” where the meeting of the needs imposed by natural necessity – the mass quenching of hunger and exhaustion by the appropriation of nature – are designed out: theirs is a synthetic freedom defined against a negative freedom that leaves the individual, sans social interference, outlined by the contingency of nature. Synthetic freedom, as it were, subsumes need as part of the construction of a new, specifically human contingency. With social production unchained from mere need, the human ends thus revealed would be able to develop within themselves as far as production would allow and freedom would “seek to expand our capacities beyond what is currently possible… open to whatever people might desire” in a co-determinative dynamic.17 If it turns out people want cake, they can eat it.

It makes sense, beyond the obvious relevance of the current environmental crisis, that this vision of luxury should be tied to nature. Bastani links communism as Marx understood it to “a spontaneous abundance similar to the Golden Age of Hesiod or Telecleides, or the biblical Eden.”18 And yet, beyond the speculative technical details of lab meat and space mining, this linkage goes curiously unexamined, in much the same way that the content of “luxury” itself does. In Greek antiquity, the mythic lifeworld of the Golden Age was made possible by a nature that gave forth plenitude without agricultural work. This vision of natural, untended abundance haunted European culture for centuries. And yet, it had only a partial relationship with the history of luxury – for example, in the pastoral motifs that recur in the painting and applied arts of the courts of Renaissance Europe.19 But even this was rarely a vehicle for propaganda for hierarchical power: Arcadia was an uncommon theme compared to the major pagan gods, and one that operated through a complex of associated concepts and affects that all had a more or less ambivalent social placement. The concept also had, perhaps even more strongly, a plebeian or vernacular existence as the Land of Cockaigne that appeared in folk literature and engravings, where the inhabitants lazed around, houses were roofed with pies and animals offered themselves for consumption. Cockaigne recurs throughout the social and millenarian movements of the early modern peasantry as one model for heaven on earth or the redeemed world.

This image of cornucopia is thus grounded in a specific vision of nature, exiled to myth, utopia or unrealised social revolt, and the values it incarnates are socially contested, claims made through the needs and desires of particular social fractions.20 The expansionists claim luxury, as a species of abundance, on behalf of the majority who have only their labour to sell, but this has no determining effect on the concept itself. Rather, its conception of need (or otherwise) and its grounding in nature are defined by the rejection of other claims, that the expansionist account projects itself as overcoming: that of the history of actually existing socialism on the one hand, and a liberal environmentalism of recycling, conservation, “sustainability” and steady-state economics on the other. That is: by different kinds of asceticism. While the former, for Bastani, is a memory of struggles that turn, in retrospect, into a mere blip in the history of technology, the latter for Williams and Srnicek falls under the heading of “folk politics”.21 Actually existing socialism spurned luxury in the conquest of need, pressing the claims of the Soviet and Eastern Bloc working classes and accordingly basing itself in a positivist conception of nature as an object to be exploited.22 Liberal or depoliticised environmentalism, in turn, rejects luxury on behalf of the needs of humanity in the abstract, issuing the command to consume less or stick to allegedly sustainable materials that all happen to come in dull earth tones, founded in a vision of nature as a homeostatic or rigid system.

This future state is defined, then, entirely by its negation of scarcity, by the fact that it realises itself on and as a material excess. Nature, as the body and substance of the realm of necessity, must be restructured in “a reconfiguration of the material world in accordance with the drive to expand our capacities for action”.23 In Bastani’s account particularly, the sundering of capitalism as organised scarcity is premised precisely on the indefinite expansion of available natural resources, creating “a problem of extreme supply, which… is difficult to reconcile with the price mechanism.” 24 Abundance negates the image of “nature” that makes capitalist social relations appear as an inalterable necessity. The pressing of the claims of need require, for the expansionists, the overcoming of need itself as founded in the concept of nature. Yet nature, whose exploitation returned onto capitalist society as this destructive image, reappears in these theories in an image somewhat different from its place in ecological Marxism: as the raw source of liberatory growth. Such a view of nature is, in one sense, a mere mirror image of the ascetic idols it sets about smashing. If E.F. Schumacher, Garrett Hardin or Buckminster Fuller once balefully insisted that Earth was a “spaceship” with tight margins on what its resources could support, with the scale and abundance of material culture reduced to an accordingly small conception of human capacities and needs, this version of post-scarcity defines itself by scaling up, quantitatively expanding, both nature and humanity, without altering either. Luxury thus represents a one-sided leverage of what Moore calls the “double internality” of humanity and nature 25. The limits presented by the embeddedness of human social production in nature are exacted as revenge on nature itself through the gambits of geoengineering and asteroid mining, ignoring the role of capital itself in shaping nature throughout the last 500 years. The claims of a currently theoretical political coalition on whatever surpasses survival are achieved not by the abolition of class society and its barbaric organisation of nature but by the forced reconciliation of technocracy. Humanity becomes ecological by fiat. Luxury becomes here another productivism, now applied to nature: it renounces renunciation by putting nature to work.

Luxury Against Luxury

It’s not disqualifying that the expansionist theory of luxury hasn’t somehow been purified of conceptual remnants from the late capitalist present, even if this does lead to some bathetic muddle, Bastani describes at some length how cellular agriculture will soon allow all the flavour and texture elements of Wagyu beef or champagne to be synthesised on a mass scale without harm to animals or soil. The question of whether they would be valued in the aesthetic scale of “taste” when they’re no longer scarce or subject to the price mechanism remains unposed, let alone answered.26 Socialists might still wonder, given these flimsy foundations and troubling implications, whether the concept of luxury is even useful for thinking the overcoming of class society’s artificial scarcity. One answer, I’d like to suggest finally, might lie in the aesthetic debates of the 19th century socialist movement as it confronted the damage that industrial capitalism had inflicted on the working class and its environment – and, in particular, the vexed example of William Morris, the designer, writer and early socialist activist against British imperialism.

At one level, Morris appeared to share the asceticism of the emergent socialist currents with which he was engaged in the 1870s and 80s. His design theories, formulated in a series of lectures and polemics, formed in reaction against the aggressive uselessness of the haute-bourgeois Second Empire style that dominated when he was a young man. Luxury design in the 1850s meant ugly fragility, swollen ornamentation, eclectic historicism, disgusting admixtures of realism and abstraction in patterning, “insensibility of the artist towards the beauty of pure shape, pure material, pure decorative pattern”, as Nikolaus Pevsner summarises it.27 He identified this as the result of industrial and highly rationalised commercial processes restructuring handicraft design practices. The “useless toil” of producing such barbarities for profit was, Morris argued, a counterpart to the cheapness and poverty of endlessly proliferating “shoddy” goods for the poor. What Engels called “the anarchy of production” found itself embodied in objects that cluttered up Victorian drawing rooms or ended up quickly deposited on refuse tips, and whose conditions of production had turned British industrial cities and coalfields into polluted hellscapes in just a few decades. This is to say nothing of what it did to the sacrifice zones of the European empires, which Morris saw carving up entire cultures on behalf of capital:

the one thing for which our thrice accursed civilization craves, as the stifling man for fresh air, is new markets; fresh countries must be conquered by it which are not manufacturing and are producers of raw material, so that ‘civilized’ manufactures can be forced on them.

Morris’s aesthetics were thus structured around a politicised concept of utility, defined by opposition to social waste and excess. The furniture and textiles produced by Morris & Co made function and beauty co-extensive. Moreover, far from advocating the full abolition of work and the social expansion of high-end design through the swelling of surplus-value, he associated such useful objects, out of the price range of the workers whose lives he most wanted to beautify, with “useful work”. The future handicraft economy he envisions in News From Nowhere (1890) is small-scale and effectively static, guaranteed by the wholesale destruction of fixed capital in revolution. The homes and public buildings of his future world, while hardly monklike, eschew the fripperies of the Victorian interior as so much trash. Describing his design theories as “prefigurative” – which News From Nowhere suggests is exactly how he thought of them – doesn’t, on its own, get us very far either. The term is, after all, now mostly a magic wand waved by anarchists to conjure away the contradictions of social forms’ embeddedness in capitalism. Meanwhile, Kristin Ross and others have pointed to Morris’s inheritance from the brief, convulsive experiment of the Paris Commune and Eugène Pottier’s concept of “communal luxury”.28 But even in Ross’s study of the same name, in which she consistently presses its relevance to contemporary socialist currents, the phrase evokes more than it explains.

In the elided difficulty of the phrase, and that of Morris’s whole critique of actually existing luxury, lies, I would suggest, its value. This difficulty hinges precisely on the relationship between the liberation of abundance and nature. In his 1884 lecture on ‘Useful Work vs Useless Toil’, Morris makes clear that he believes “Nature wills all men either to work or starve” and that the abolition of classes will involve a redistribution of work that leaves no-one the option of idleness. Curiously, he shares with the expansionists the claim that such work would “take up but a small part of each day” and that the “labour-saving” machinery he elsewhere attacks should be “used for minimizing the amount of time spent in unattractive labour”.29 Yet he avers that the “happy and useful work” of such a future society wouldn’t be guided by the social calculations of “mere utilitarianism”. A phrase like “the attractiveness of labour” quite rightly makes anyone who’s worked in a call-centre, or even as a content artisan, wince. Moreover, on its face the notion of “useful work” could hardly be further from the icy, transfigured reality of abstract labour-power revealed in Marx’s major economic writings. Under capitalism, the production of use values in the labour process is, as it were, a mere necessary evil in exchange value’s self-generation, such that carpentry and advertising are, from one perspective, indistinguishable. And yet, as Edward Thompson notes, it was precisely his reading of Marx that lead Morris to his late aesthetic theories, focused so thoroughly on contemporary struggles over the terms and implications of work30. But in a real sense, the “cheerful” nature of such labour is not about labour itself nor even its handicraft or machine quality, but labour’s place in society’s metabolic relationship with nature.

What justifies such labour, what constitutes its pleasure, is its “useful” end. But its “use” does not consist strictly in producing what Marx calls use-values. After all, even the foulest and most meagre factory-made furniture or foodstuff has a use-value. Rather, the question of use cannot be seen outside of the concept of need discussed earlier, as the subject of a “moral and historical element” in class struggle. As we have seen, “luxury” is revived in capitalism as a form that promises democratisation and reinstates hierarchy in one movement, a surplus value that accrues to no use but embodies a contradictory movement within capital accumulation against the bourgeoisie itself. The claim of the workers’ movement on the total social product, then, would involve a qualitative transformation of “luxury” that would realise the category only in its abolition, opening up the possibility of the exploration of “free needs”. For Morris, labour can have no use without pleasure: the scarring and destructive labour of industrial profit-seeking has, strictly, no use or issue except the perpetuation of wasteful labour itself, “compulsion by man to labour in hope – of living to labour!” – exchange-value that grows autonomously without reference to the beings that constitute it, returning as mere survival in the alienated form of wages. The “wealth” to which labour’s ends can be turned is, rather, “what Nature gives us and what a reasonable man can make out of the gifts of Nature for his reasonable use.” He reiterates that, although machinery appears to have made the appropriation of nature through labour much easier (at least from capital’s point of view), “Nature will not finally be conquered till our work becomes a part of the pleasure of our lives.” Importantly, he characterises such work not as the production simply of the necessaries dictated by the compulsions of nature, but “the ornamental part of life”. Utility here becomes, through the qualitative revaluation of labour lifted out of exchange, luxury.

A backward glance to the “Popular Art” of Gothic stonework suggests that the collapse of a hierarchy between utility and luxury would be the corollary of the abolition of the division of labour. “The craftsman, as he fashioned the thing he had under his hand, ornamented it so naturally and so entirely without conscious effort, that it is often difficult to distinguish where the mere utilitarian part of his work ended and the ornamental began.” In other words, Morris’s “utility” is the construction of a value beyond the binary of use and the useless, where use, following its own spiralling logic, conjoins itself into an ornament that embodies in its substance the inner consistency of nature in its constitutive relation with humanity. It is an ecological labour that unfolds a luxury that takes its contours from labour’s place in nature and nature’s place in the process of human flourishing – a labour that finally does conjoin the realms of necessity and freedom.

This isn’t to suggest that a luxury ecosocialist development out of the present will resemble some cottagecore meme of be-smocked clear-skinned white woodcarvers – although no doubt even the expansionists would admit there would be room for handicraft labour in the liberty of an automated communism. If nothing else, building such airborne castles in a present where the institutions of solidarity have been systematically destroyed would amount to a parlour game. It is, rather, to try and reframe the problem of luxury, to suggest the potential and the actually existing impasse that lies behind even the practical examples of “communal luxury” enumerated by Morris and, before him, Pottier. In closing, I want to circle for a moment back to the practical, or the point where the concrete makes the abstract visible – namely, to aesthetics.

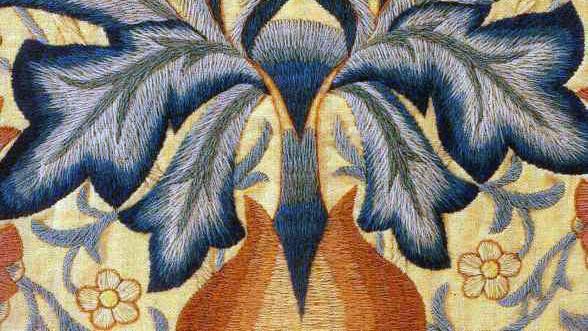

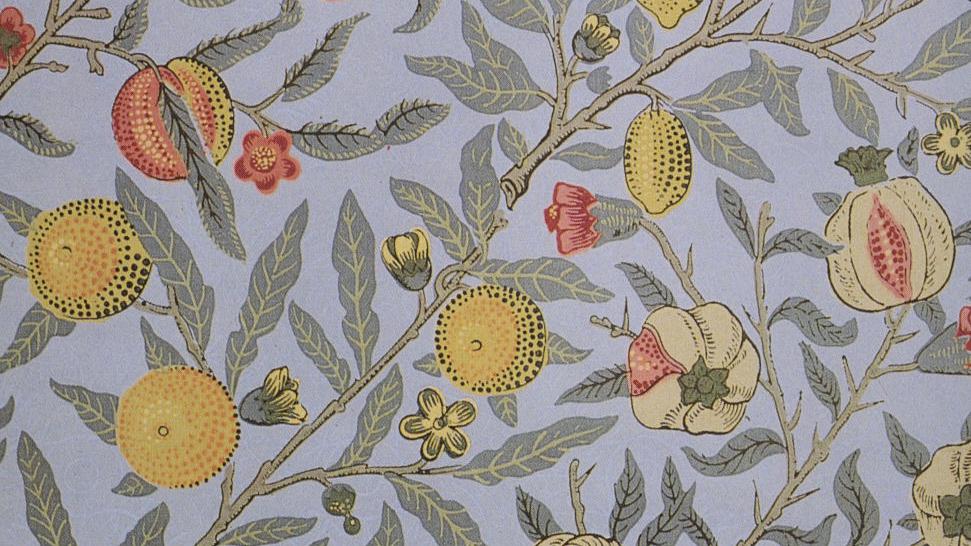

In Morris’s own case, the image of the “use” that his theories gestates can be seen in his pattern-designs. Apart from the oft-mentioned abolition in Morris’s work of the division between fine and applied art, what’s striking in his textile and wallpaper designs is the way that what Pevsner calls “the decorative law of the coherence of surfaces”, spreading out in a flat, theoretically infinite repetition intersects with the elaboration of plants’ growth 31. In such patterns as ‘Honeysuckle’, ‘Fruit’, ‘Vine’ and ‘Willow Bough’, obsessive observation of natural detail is allied to a form of craft abstraction (Morris & Co’s wallpapers were block-printed, their carpets hand-knotted). Nature is freed from the genre of landowners, the modern easel landscape, with its spatial recession and singular viewpoint surveying a land structured by enclosure and industrialisation. Its movement across a flat space is governed by a logic inassimilable to human use.

In a brief analysis of the place of luxury in mass culture 70 years later, Theodor Adorno seizes on such a communal luxury as a moment briefly visible in “the whole dialectic of enlightenment”.32 In words that should serve as a warning to the expansionists, he notes that industrial capitalism had generalised access to certain forms of luxury but had not declared “privilege a human right”. Rather, it combined a raised standard of living with “cutting off the possibility of fulfilment”, eliminating “the utopia of the qualitative” through luxury’s rigid standardisation.33 While luxury persists as kitsch, the austerity of modernist art – presaged in Morris’s strange combination of flat, quotidian abstraction and a craft attention to nature – can be seen as preserving the possibility of what luxury once promised. “To the aesthetic eye, which sides with the useless against utility, the aesthetic, when severed violently from purpose, becomes anti-aesthetic, because it expresses violence: luxury becomes brutality.” 34 Yet this uselessness, like the “idolization” that a child recognises in the hoards of non-fungible jewels in The Arabian Nights – extracted by human labour from the bowels of nature – presents an element in the dialectic that use cannot solve. In Morris’s work can be seen a use that embodies the uselessness of nature, his severe luxury describing a “fleeting shape [that] attests to the avoidability of terror.” 35 Socialists could learn from such examples how to orient themselves towards the luxury of a properly free world.

-

Karl Marx. [1894]. 1991. Capital: A Critique of Political Economy, Volume III. Translated by David Fernbach. London: Penguin. p. 959. ↩

-

Marx. Capital, Volume III. p. 959, 958. ↩

-

Aaron Bastani. 2020. Fully Automated Luxury Communism: A Manifesto. London: Verso. p. 50. ↩

-

Bastani. Fully Automated Luxury Communism. p. 137, 160. ↩

-

Jason W. Moore. 2015. Capitalism in the Web of Life: Ecology and the Accumulation of Capital. London: Verso. p. 286. ↩

-

Theodor W. Adorno. [1945]. 2020. Minima Moralia: Reflections from a Damaged Life. Translated by E. F. N. Jephcott. London: Verso. p. 120. ↩

-

Thorsten Veblen. [1899] 1934. The Theory of the Leisure Class: An Economic Study of Institutions, New York: The Modern Library. pp. 68-101. ↩

-

Nick Srnicek and Alex Williams. 2016. Inventing the Future: Postcapitalism and A World without Work. London: Verso. p. 80. ↩

-

Marx. Capital, Volume III. p. 958. ↩

-

Marx. Capital, Volume III. p. 959. ↩

-

Karl Marx. [1885]. 1991. Capital: A Critique of Political Economy, Volume II. Translated by David Fernbach. London: Penguin. p. 479. ↩

-

Quoted in Agnes Heller. [1974]. 2018. The Theory of Need in Marx. London: Verso. p. 30. ↩

-

Quoted in Heller. The Theory of Need in Marx. p. 30. ↩

-

Heller. The Theory of Need in Marx. p. 38. ↩

-

Mark Fisher. 2012. “Postcapitalist Desire” in What Are We Fighting For: A

Radical Collective Manifesto. Edited by. Federico Campagna and Emanuele Campiglio. London: Pluto Books. pp. 328–329. ↩ -

Mark Fisher. 2018. “Acid Communism: Unfinished Introduction” in edited by Darren Ambrose. K-Punk: The Collected and Unpublished Writings of Mark Fisher, 2004-2016. London: Repeater. p. 850. ↩

-

Srnicek and Williams. Inventing the Future. p. 80. ↩

-

Bastani. Fully Automated Luxury Communism. p. 54. ↩

-

See, for example, Malcolm Bull. 2005. The Mirror of the Gods: Classical Mythology in Renaissance Art. London: Allen Lane. p. 238. ↩

-

It’s worth noting that there are other conceptions of luxury that explicitly associate it with the rejection or supersession of nature – with the artificial, unnatural, alien or ornamental – that can be seen in such diverse sources as gangsta rap, the films of Douglas Sirk, Roxy Music, Art Deco, kosmische music, Expressionist architecture and Pop Art. Although Bastani flirts at times with such traditions, the expansionist account, probably conditioned by the need to present realistic, if maximalist, political programs, doesn’t ultimately associate itself with them. Nature is at every point present in the expansionist theory of luxury, if only as an unconscious problem. ↩

-

Srnicek and Williams. Inventing the Future. p. 12. ↩

-

There were, of course, much more complex cultures both of ‘democratic’ material luxury and environmental thinking in the Soviet system, particularly in the decades beginning with the “Khrushchev thaw”. On the former, see for examples, Amy E. Randall. 2008. The Soviet Dream of Retail Trade and Consumption in the 1930s (London: Palgrave Macmillan); Jukka Gronow, Caviar with Champagne: Common Luxury and the Ideals of the Good Life in Stalin’s Russia. Leiden: Brill. On the latter, see: John Bellamy Forster, ‘Late Soviet Ecology and the Planetary Crisis’,. The above is intended, rather, as a broad sketch of the place that the Soviet experiment occupies in the FALC political imaginary. ↩

-

Srnicek and Williams. Inventing the Future. p. 82. ↩

-

Bastani. Fully Automated Luxury Communism. p. 134. ↩

-

Moore. Capitalism in the Web of Life. p. 1. ↩

-

Bastani. Fully Automated Luxury Communism. p. 179. ↩

-

Nikolaus Pevsner. [1936]. 1991. Pioneers of Modern Design from William Morris to Walter Gropius. London: Penguin. p. 43. ↩

-

Kristin Ross. 2015. Communal Luxury: The Political Imaginary of the Paris Commune. pp. 60-65. ↩

-

Whether currently unpaid domestic work would come under the heading of this “unattractive labour” is worth acknowledging as a sore point for Morris’ reception after feminism. Famously, in News From Nowhere the women characters are cast in occupations of child-raising and housework – perhaps important in Morris’ eyes but often thankless for those undertaking it. Williams and Srnicek contend that such work could, with some success, be automated (Inventing the Future, pp. 113-4). Sophie Lewis and David M. Bell have criticised this claim, although their own argument around the “invisible” nature of socially reproductive labour to socialist planning is only half-convincing. ↩

-

E. P. Thompson. 1977. William Morris: Romantic to Revolutionary. London: Merlin Press. p. 641. ↩

-

Pevsner. Pioneers of Modern Design. p. 53. ↩

-

Adorno. Minima Moralia. p. 121. ↩

-

Adorno. Minima Moralia. pp. 119-20. ↩

-

Adorno. Minima Moralia. p. 121. ↩

-

Adorno. Minima Moralia. p. 121. ↩