EDITION: ECOLOGIES.

Call of Duty: Black Ops Cold War ideologically attempts to present "the unholy trinity" of violent repression carried out by the US in Central America as both exciting and necessary.

Released in November of last year, Call of Duty: Black Ops Cold War is the latest instalment in the popular and lucrative first-person-shooter series. Its publisher, Activision, claims that the game is “inspired by true events” as players “come face-to-face with historical figures and hard truths”, but the game’s marketing campaign also included a tie-in promotion with Bachelor’s Super Noodles, which perhaps signalled that a respectful depiction of harrowing historical events was not really a priority for company executives.

Indeed, while the game does include uncanny depictions of Ronald Reagan, Alexander Haig, James Baker and Mikhail Gorbachev, its plot fails to portray the realities of the Cold War. Instead, the game provides fanciful, bombastic action as the player takes control of a CIA operative tasked with foiling a rogue Soviet agent, codenamed Perseus, who plans to detonate several nuclear weapons throughout Europe. Over the course of the story, the player undertakes covert missions with their CIA team in a globe-trotting adventure across East Berlin, Cuba, Turkey and the Soviet Union.

In one early scene in the game, Alexander Haig questions the legality of the CIA’s in-game actions, which include extrajudicial killings, but Ronald Reagan defends the team. In the President’s words, the player is “protecting our very way of life from a great evil. There is no higher duty, there is no greater honor.” Thus, rather than denying that CIA agents could conceivably take part in illegal actions, the game justifies those actions as necessary to preserve Western lives, with the victims of US violence always being deserving bad guys. As one CIA agent puts it late on in the game, “Some of us will cross the line, to make sure the line’s still there in the morning.”

Unlike the game’s central plot, its portrayal of Ronald Reagan – as a Cold War warrior who saw conflict with the USSR as an ideological battle between competing ways of life – has basis in reality. In 1977, while the US-Soviet relations were in a period of détente, Ronald Reagan explained that his “idea of American policy toward the Soviet Union is simple, and some would say simplistic. It is this: We win and they lose.”

In the years leading up to his election victory in 1980, left-wing armed insurrections in El Salvador and Guatemala, along with successful revolution in Nicaragua, led Reagan and his advisors to view Central America as a particularly crucial theatre in the global Cold War. In his campaign against incumbent President Jimmy Carter, Reagan claimed that his opponent had “managed to alienate our friends in the hemisphere, to encourage the destabilization of governments, and to permit Cuban and Soviet influence to grow.”

After assuming office, Reagan pursued an aggressive policy to roll back Soviet influence around the globe. This so-called Reagan Doctrine was encapsulated in the 1983 NSC National Security Decision Directive 75, which described the aim of US policy as “to contain and over time reverse Soviet expansionism”. The document argued that:

The U.S. must rebuild the credibility of its commitment to resist Soviet encroachment on U.S. interests and those of its Allies and friends, and to support effectively those Third World states that are willing to resist Soviet pressures or oppose Soviet initiatives hostile to the United States, or are special targets of Soviet policy. The U.S. effort in the Third World must involve an important role for security assistance and foreign military sales, as well as readiness to use U.S. military forces where necessary to protect vital interests and support endangered Allies and friends.”

This strategy was applied across the Global South but held particular significance for Central America, which Reagan’s Ambassador to the United Nations, Jeane Kirkpatrick, described as “the important place in the world for the United States.”1 It led US officials to view conflicts in Central America not as struggles between competing national groups and interests, but as flashpoints in a superpower conflict. Furthermore, in putting the Reagan Doctrine into practice, the US Government facilitated what Greg Grandin has termed, “The Unholy Trinity” of death squads, disappearances and torture in El Salvador, Guatemala and Nicaragua.

Over the course of Reagan’s two terms in office, Washington provided the Salvadorian Government with more than a million dollars a day to fund its civil war against left-wing insurgents.2 By 1983, the CIA had some 150 agents operating in the country and almost all Salvadoran military officers had been trained by the United States. In 1984 it was revealed that top members of the army, the police forces, and the paramilitary forces were being paid retainer fees by the CIA.3 An estimated 75,000 people were killed in the war that raged from 1979 to 1992, with a UN Truth Commission later finding that almost 85 percent of the killings, kidnappings, and torture had been the work of government forces, which included paramilitaries, death squads, and army units trained by the United States.

Reagan’s terms as President also coincided with the most violent period in the civil war between the Guatemalan Government and left-wing rebel groups, which claimed 200,000 lives between 1960 and 1996. After becoming President, Reagan worked to overturn legislation that prevented him from supplying military aid to the Guatemalan government, despite receiving reports that its military was indiscriminately killing civilians and carrying out a genocide of the Mayan population.

In 1982, just as the Reagan administration was being told by its own officials that “the military continues to engage in massacres of civilians in the countryside”, the US President continued to insist in public that his Salvadorian counterpart, Ríos Montt, “had been getting a bad deal” from his critics and that he was “totally committed to democracy.”4 By 1986, the ban on military aid had been lifted and the US was delivering an estimated $109.5 million in economic and military assistance to Guatemala.

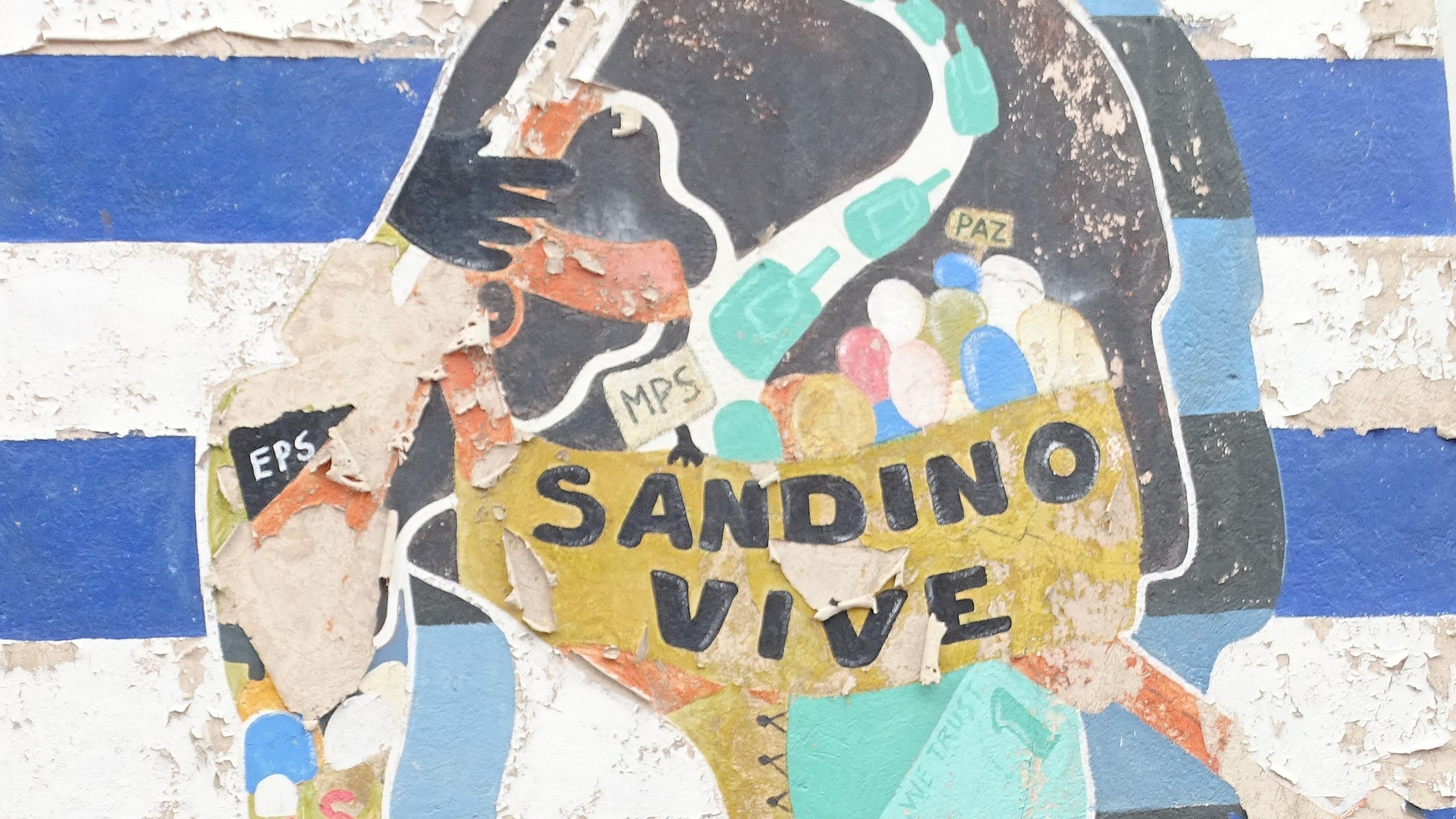

Similarly, in 1981, Reagan also authorised the CIA to support the Nicaraguan paramilitary forces collectively known as the Contras. Throughout the 1980s, the US-backed Contras indiscriminately kidnapped, murdered, tortured and raped thousands of Nicaraguan civilians in a terror campaign designed to reduce support for the left-wing Sandinista government.5 To assist the Contras, the CIA produced a training manual entitled ‘Psychological Operations in Guerrilla War’, which explained how the right-wing rebels should justify themselves if “it should be necessary […] to fire on a citizen who was trying to leave the town or city in which the guerrillas are carrying out armed propaganda or political proselytism”. Under the heading ‘Selective Use of Violence for Propagandistic Effects’, the manual also advised that it was “possible to neutralize carefully selected and planned targets, such as court judges”.6

To generate support for its foreign policy objectives at home, in 1983, the Reagan administration established the Office of Public Diplomacy for Latin America and the Caribbean. The Office focused its work on eulogising the Contras, promoting them as “freedom fighters fighting in the American tradition”, while condemning the Sandinistas as “evil” “puppets” of the Soviet Union.7 Despite this publicity effort, in 1986, the International Court of Justice found that Washington’s support for the Contra’s campaign was illegal and ordered the US Government to pay reparations to Nicaragua. However, the Reagan administration boycotted the case and refused to abide by the ruling.

Over the course of these conflicts, several former death squad members testified that US advisors were not only aware that their allies in Central America were using torture but they in fact taught its use. The euphemistically-titled Human Resource Exploitation Training Manual was an interrogation handbook used in Central American countries by CIA and Green Beret trainers between 1983 and 1987, which taught psychological torture. It advised that an interrogator “is able to manipulate the subject’s environment” in order “to create unpleasant or intolerable situations, to disrupt patterns of time, space, and sensory perception.”

After Congress and the press began to investigate the use of CIA training techniques in Central America, the manual was hand-edited sometime between 1984 and early 1985 to alter passages that encouraged torture. For example, the sentence “While we do not stress the use of coercive techniques, we do want to make you aware of them and the proper way to use them” was altered to “While we deplore the use of coercive techniques, we do want to make you aware of them so that you may avoid them.”

This record of Reagan’s interventions in Central America is in sharp contrast with Call of Duty’s depiction of the Cold War, despite Activision’s claims that its game “drop[s] fans into the depths of the Cold War’s volatile geopolitical battle of the early 1980s”. People in Central America certainly experienced the Cold War as a “volatile geopolitical battle”, but not as the series of action set-pieces depicted in Call of Duty. At one point in Black Ops Cold War, Ronald Reagan explains that the CIA has been tasked with “preventing an attack on the free men and women on the world” but, in reality, it was CIA-backed dictatorships and paramilitary groups that often abused and murdered civilians in Central America.

The fact that this fictionalised history of US policy is disseminated through a video game is also significant as the player is not merely a passive consumer of Black Ops Cold War’s narrative, but an active participant within it. To progress in the game, players must complete objectives that reflect the aims and perspectives of the CIA, which are justified narratively by the fantastical and existential threat posed by Perseus. At the same time, the unsympathetic Perseus and his allies, who wish to empower the Soviet Union by bringing about the nuclear annihilation of Europe, are the only characters in the game to voice objections to the USA’s dominant world role. Late on in the story, the player is given the option of betraying the CIA and siding with Perseus, but this simply results in the destruction of Europe and is clearly intended to be the ‘bad ending’. A critique of US interventionism based on the principles of anti-imperialism and universal human rights, which players may have found more persuasive, is left unexplored.

While the game’s narrative makes clear that the loss of European lives would be disastrous and should be prevented, conflicts in the Global South merely serve as backdrops to action set-pieces. Players are never encouraged to reflect on the very real destruction and loss of life that resulted from Cold War imperialist interventions in the Global South. In flashback portions of the game set during the Vietnam War, for example, players are tasked with mowing down waves of Viet Cong but are not encouraged to consider the morality of their in-game actions nor the devastation caused by real war. As such, the game reproduces a Eurocentric view of the Cold War with Western European lives placed above the lives of those living in the Global South.

In fact, it is only relatively recently that historians in the Global North have made a concerted effort to study the Cold War as a truly global, rather than predominantly European, conflict. This most recent historiography has analysed how a Cold War framework shaped localised events around the world, while also acknowledging the agency of people, groups and governments in the Global South.8 Sadly, these efforts to incorporate a range of perspectives and experiences into our understanding of the Cold War are not reflected in Black Ops, nor popular culture more generally.

By placing players in the role of a CIA operative within an ahistorical narrative, Black Ops Cold War normalises and justifies US interventionism, while obscuring its brutal reality. Even those aspects like the rendering of Reagan’s Manichean view of the Cold War or US intervention in Vietnam, which are factually correct, are articulated in a context that deprives them of any possible critical value. The distance required to make a critical judgement is cancelled by the form of the game.

This is not the first time that a Call of Duty game has white-washed the grim results of US actions in Central America during the Cold War. An earlier instalment in the series, Black Ops II, included a cameo from Oliver North, who advised the game’s creators and featured prominently in its advertising campaign. North is notorious for secretly and illegally, channelling financial support to the Contras during Reagan’s presidency in what became known as the Iran-Contra affair. Unsurprisingly, Black Ops II failed to acknowledge the impact of North’s actions on the people of Nicaragua, just as the most recent game in the series fails to hold Ronald Reagan accountable.

The military establishment is aware of the powerful ways in which ideology can be disseminated through video games and, in fact, the US Army launched its own game, America’s Army, in 2002. The game was intended principally as a recruitment tool, with Major Chris Chambers, Deputy Director of the Army Games Project, explaining that it allows the military “to make connections with Americans who might not have had a connection with the Army. We use the videogame to make that connection”.9

The terrible abuses perpetrated by US-sponsored regimes and paramilitaries have left a traumatic legacy throughout Central America and helped foster the political destabilisation that exists in the region today. Given its failure to reckon with the consequences of US interventionism, it is particularly galling that advertisements for Black Ops Cold War featured the tagline “Know your history or be doomed to repeat it”. Nevertheless, that old cliché does hold some merit – understanding the history, legacy and enduring features of US imperialism is important if we are to resist it in the present. In that sense, Call of Duty provides a useful case study in examining how popular media can be used to sanitise, justify and generate public support for imperialism.

-

Peter H. Smith. 2008. Talons of the Eagle, Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 171. ↩

-

Greg Grandin. 2007. Empire’s Workshop: Latin America, the United States, and the Rise of the New Imperialism. NY, New York: Holt Paperback. p.71. ↩

-

Frederick H. Gareau. 2004. State Terrorism and the United States: From Counterinsurgency to the War on Terrorism. Atlanta, GA: Clarity Press and Zed Books, 2004. p. 31. ↩

-

Greg Grandin. 2011. The Last Colonial Massacre: Latin American in the Cold War, 2nd edition. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. p. 188. ↩

-

Grandin. Empire’s Workshop. pp. 112-117. ↩

-

Holly Sklar. 1988. Washington’s War on Nicaragua. Cambridge, MA: South End Press. pp. 177-183. ↩

-

Grandin. Empire’s Workshop. pp. 123-130. ↩

-

For example: Odd Arne Westad. 2006. The Global Cold War: Third World Interventions and the Making of our Times. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.; Max Guderzo and Bruna Bagnato (eds). 2010. The Globalization of the Cold War: Diplomacy and Local Confrontation, 1975-85. London: Routledge. ↩

-

Cited in Ed Halter. 2006. From Sun Tzu to Xbox: War and Video Games. New York, NY: Thunder’s Mouth Press. p. x. ↩