EDITION: Bad New Times.

'Burn it Down' documents the fundamental optimism of feminist movements; the belief that things can change.

When I finished writing this book review a few weeks ago, its beginning was focused on cynicism, on believing that nothing good, on a large-scale political or climate-related level, will ever happen in our lifetimes; on the feeling that drifting out to sea one day is a legitimate retirement plan; on doing activism despite believing the future is bleak. Since then, led by Black Lives Matter, the world has erupted in the most widespread uprising against racism most of us have lived through. And behind this energy is hope; that a world without racist killings is possible, that a world without racism is possible, that structural inequality and violence is not inevitable.

Against any lingering feeling that nihilism is an acceptable response to the world we live in, Breanne Fahs’s edited collection Burn It Down: Feminist Manifestos For The Revolution (published by Verso) documents the optimism of political movements, in this case feminist. Behind most manifestos is not twee positivity – more frequently, rage – but always a spark of hope, perhaps not that the world will ever be completely fair and sweet but that, by presenting an ideal, we can move a little further toward it.

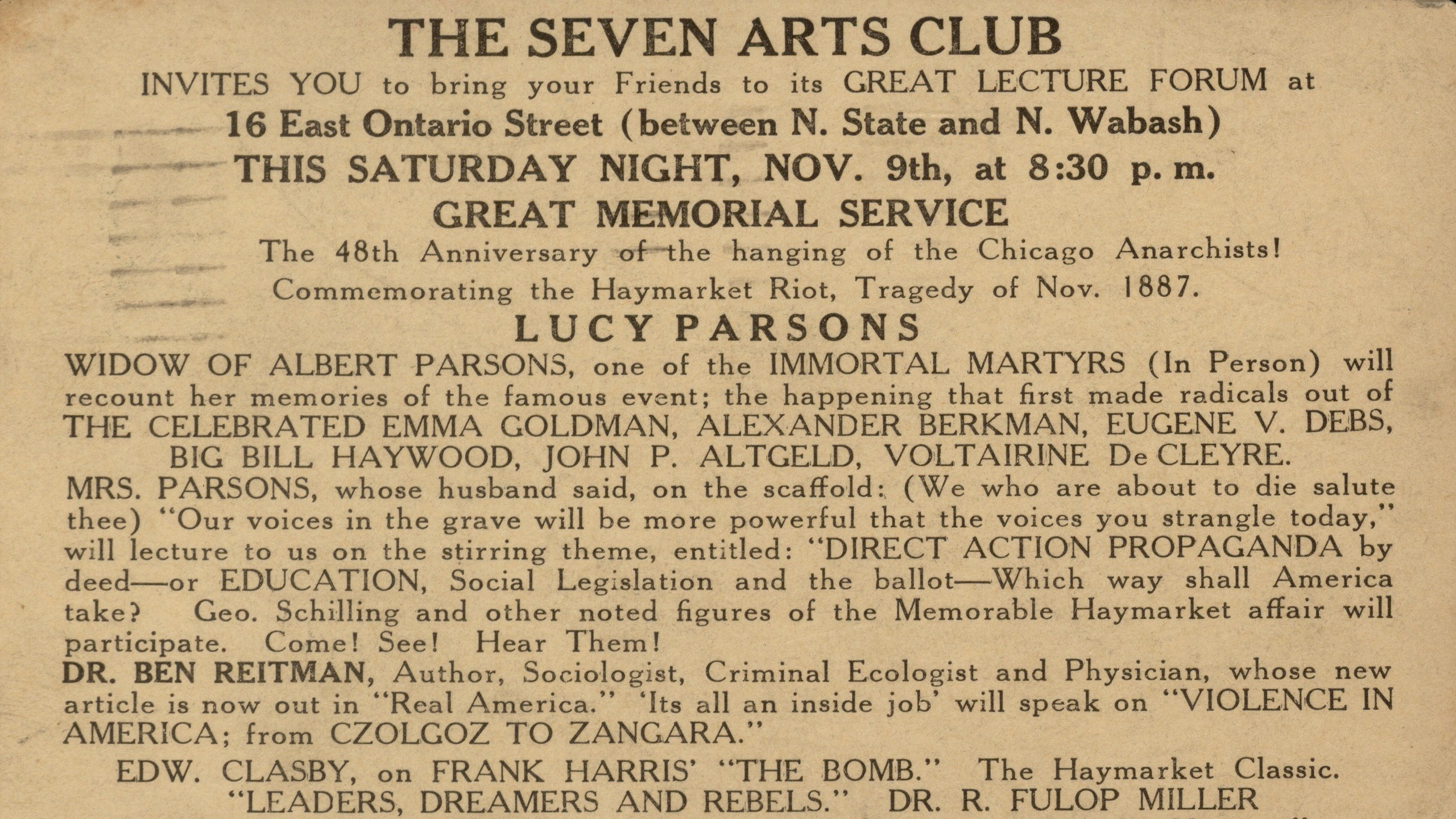

Burn It Down sweeps through time and across the globe. There’s no consensus in the goals of the manifestos but all share the belief that another world is possible. To write a manifesto is to lay out a blueprint. The best are without restraint. Take radical labour organiser and anarcho-communist, Lucy E. Parsons’, 1884 text, To Tramps, the Unemployed, the Disinherited, and Miserable.

You were only a tramp now, to be execrated and denounced as a “worthless tramp and vagrant” by the very class who had been engaged all these years in robbing you and yours. Then can you not see that the “good boss” and “bad boss” cuts no figure whatsoever? That you are the common prey of both, and that their mission is simply robbery?

Parsons, the daughter of a slave, called “more dangerous than a thousand rioters” by the Chicago Police Department, recommends as a salve: “Learn the use of explosives!”

You won’t be on side with everyone you meet in this collection but you’ll be energised by their passion. Andrea Dworkin is here, in all her problematic glory, with Intercourse, her 1987 screed against the possibility of heterosexual sex ever being free from the cultural baggage of oppression. “The normal fuck by a normal man is taken to be an act of invasion and ownership undertaken in a mode of predation.” It’s possible to look critically at Valerie Sonalas’ biological essentialism but still be rapt by the SCUM (Society for Cutting Up Men) Manifesto with its celebration of “hateful, violent bitches who’d sink a shiv into a man’s chest or ram an icepick up his arsehole as soon as look at him”.

Burn It Down splits the collection into sections: Queer/Trans, Anticapitalistic/Anarchist, Angry/Violent, Indigenous/ Women of Colour, Sex/Body, Hacker/Cyborg, Trashy/Punk and Witchy/Bitchy. Each section has an introduction but, largely, you’re left to do your own homework as to where each text is situated in overlapping feminist movements.

There’s the 1969 Redstockings Manifesto, claiming that, “Male supremacy is the oldest, most basic form of domination. All other forms of exploitation and oppression (racism, capitalism, imperialism, etc.) are extensions of male supremacy.”

And here’s Linda La Rue in 1970: “Any attempt to analogise Black oppression with the plight of the American white woman has the validity of comparing the neck of a hanging man with the hands of an amateur mountain climber with rope burns.”

Burn It Down includes iconic texts: ACT UP’s 1990 Queer Nation Manifesto; Emma Goldman’s 1896 Anarchy and the Sex Question; Shulamith Firestone’s 1970 Dialectic of Sex; the 1977 Combahee River Collective Statement; Donna Haraway’s 1991 Cyborg Manifesto.

You’ll also find Bikini Kill’s 1991 RIOT GRRRL Manifesto, the Bloodsister’s Project’s 1996 poem, “Ax Tampax Poem Feministo”, McKenzie Wark’s 2004 Hacker Manifesto, the 1968 W.I.T.C.H Manifesto.

In 1907 China, He-Yin Zhen stated that many women would die in the feminist revolution but that, “Would we not rather unleash destruction and die on the battlefield for posthumous honour than be oppressed to death as obedient concubines?” And here’s Paul Preciado in 2000 with his tongue-in-cheek manifesto which calls for a countersexual revolution via “dildonics” and sexual plasticity: “I renounce all the privileges and obligations that could derive from the unequal power positions generated by the consensual use and re-inscription of dildos within the framework of this contract.”

All organised social change began with someone’s refusal to drift out to sea, with hopefulness. Utopian thinking has always seemed delusional to me but maybe I’ve misunderstood its point. In real and concrete ways people are changing the world according to utopian ideals all the time. Every piece of activism, every call for a fairer world is an act of faith that a different society is within reach.

If anything good comes out of the pandemic, it’ll be at grassroots level. In Envisioning Real Utopias, Erik Olin Wright suggests that blueprints for fairer structuring of society already exist in organisations such as workers’ cooperatives, in any group organised on an anti-capitalist basis. Right now, in mutual aid schemes, renters unions, food banks, Covid-19 fundraisers, in the work of activist groups doing everything they can to stop communities going under, people’s utopian ideals are made concrete. Utopian thinking exists in calls for universal basic income, for defunding the police, for prison abolition, for the decriminalisation of sex work. None would solve everything but all would rearrange a small part of the world in a way that is less broken.

In 2017 and 2019, Corbyn’s manifesto was written off as a wild flight of fancy. The vast majority of the population is sceptical about the possibility of radical change. It’s harder to dismiss something already manifest in front of you, tiny changes, small “utopias” on your street. And alongside these small utopias – behind them – are people’s huge, undaunted dreams. Writing a blueprint for society, a manifesto, is hopeful. The Overton window has slipped far to the Right but with each concrete act or written declaration of intent, it can be shifted. Nihilism is not an option.