EDITION: Bad New Times.

We asked for responses on radical organising in response to Coronavirus. Next, we're asking for responses on London-centricity.

As the full impact of the coronavirus pandemic started to be felt in March, New Socialist turned the attention of the Activists’ Inquiry towards recording the experiences of radical organising which the crisis was throwing up. We’re publishing the results of this inquiry – eight responses in total, all on mutual aid – below.

A number of different themes traverse all of the contributions. We were struck by the speed with which the mutual aid groups were started and how quickly they took on quite a wide range of functions. There was a real sense that the role and remit of the mutual aid groups was ‘in the air’ – struggles immediately began, whether openly or not, over what they should look like and what they should not. Activists came from a range of backgrounds and they repurposed things they’d taken from other kinds of activism and the workplace – as noted in our piece on ‘strategy and tactics’, and in one of the contributions, many groups were quick to make use of the work of the transfeminist autonomous group QueerCare, without that necessarily representing the official politics of most mutual aiders.

Contributors also drew attention to divisions within the mutual aid groups and their limitations, including some of the dangers which josie highlighted in her essay for New Socialist. These divisions speak to the spontaneity of the mutual aid groups and make clear the value of involving oneself in addressing them. It’s not obvious in any of the submissions that these questions were somehow already settled from the outset – they were live. The submissions raise binary oppositions like democratic vs. accountable, central vs. local, and charity vs. solidarity. If some of the submissions suggest that the involvement of politicians was not as great as might have been feared, they also deal with the problems which some activists’ backgrounds as social workers or in the charity sector could introduce. Perhaps above all, activists dealt with the challenges of being perceived as ‘making things political’ when, as we know, the crisis was political all along. The ways in which something as suggestive of a different world as mutual aid can be undermined and hemmed in are important for us all to consider – but it’s only in confronting these obstacles that we learn ways of overcoming them.

Whilst we were pleased with the contributions which we received, it is important to note the limited geographic area from which they have come—six submissions from London, and two from south-east England. The preponderance of contributions from London has dogged the Activists’ Inquiry and, whilst no surprise to anyone familiar with the geography of the Left in the UK, is a cause for concern. As was addressed repeatedly in our interviews with the candidates for the Momentum NCG, the Left’s London-centricity is a reflection of the London-centricity of the UK – and (although noting that the ‘London’ which is thereby centred is never reflective of London as a whole) overcoming this problem will require moves by the Left to centre other places.

The next Activists’ Inquiry will therefore focus on these problems. We’re interested in submissions which respond to questions such as:

- What obstacles do activists outside London face?

- What have your experiences been in conducting activism (such as attending demonstrations) in London, as an activist from elsewhere? Were these negative or positive experiences? What types of organisation did this require?

- To what extent has access to resources been limited by being outside London?

- How have analyses applicable to London been extended, correctly or incorrectly, to other areas? What have been the consequences of this?

- How does your relationship to London differ or compare to your relationship with other metropolitan centres, like Manchester?

- To what extent can the role of Cardiff within Wales be compared to the role of London? How does the distinction between the capital and the largest city impact the comparison for Scotland?

- How do national questions interact with the notion of London-centricity? For example, what does it mean for London to be treated as a synecdoche for England or the United Kingdom (e.g. “Westminster”, “the London Parliament”)?

- For activists in London, what problems has London-centricity caused in the capital? How does this weigh against the advantages?

We’re also interested in learning about attempts to break with or overcome the problems of London-centricity, and questions such as:

- What has been your experience with attempts to devolve power and resources from organisations’ London headquarters to e.g. regions?

- Has an organisation in which you’ve been involved attempted to move its headquarters elsewhere? What were the results of this?

- Similarly, what has been your experience of national events (conferences, demonstrations) which have occurred outside London?

- On an individual level, has your activism influenced your choice of where you live? Have you considered moving elsewhere for political reasons?

Contributions of fewer than 500 words, as well as images, should be submitted here.

If you would like to make a longer contribution, or have difficulty using the form, please submit them to [email protected] and (like all contributions) we will publish them anonymously.

Woman, South-East England

Our mutual aid group started as a Facebook group and an old mobile phone with a GiffGaff SIM card to be used as a ‘hotline’ for local residents to call. In a few short weeks it has evolved into a citywide multi-phone hotline system and a network of local ward WhatsApp groups, co-ordinated through a Slack group made up of WhatsApp co-ordinators, Facebook admins, hotline operators, tech people, and NHS/charity liaisons.

The main source of conflict has been between those who want to keep things democratic and accountable and uphold the principles of mutual aid and those who see this as a barrier to pragmatism and safeguarding. The whole process of linking those who can offer something and those who need something has become very bureaucratic and we’ve had to actively work to try and stop things becoming completely beholden to the tech. The system we have is genuinely very good but is in danger of being used to meticulously log everything for the sake of it rather than to simply facilitate the process of mutual aid. We’ve had to argue many times that it’s okay for neighbours to ask each other for help in their local WhatsApp group and organise amongst themselves without the request needing to be logged via the ‘official’ system. There have also been concerns with police involvement, and a complete lack of understanding that a mutual aid group should be a safe space for people who might be put at risk by police involvement.

Many of the people in the Slack group seem to be happy for decisions to all be made by a group of 4 or 5 ‘admins’ with no real scrutiny. Most of them are very well-meaning but not very political, which has made it difficult to question the actions of the admins without being seen as troublemakers ‘making things political’ and criticising their hard work. This has been papered over with an agreement to handle disagreements in separate Slack channels so to as not upset people who don’t want to be involved, but hasn’t really solved the underlying lack of democracy and accountability.

There is no real concept of the group being an actual mutual aid group, and we are constantly trying to steer the group away from a charity or service mindset. That has been made difficult by the fact that we are now filling quite a large gap in provision that the ‘official’ providers simply can’t meet. We are now able to refer people for food bank vouchers, and we’re working with the council and local NHS trust. We’ve even had ‘permission’ from the police to continue delivering flyers to areas that haven’t had them yet. Perhaps once the COVID-19 crisis is over the group can be repurposed into a true mutual aid group, but at the moment we’re just doing our best to get as many people as possible through this and out the other side.

Man, Greater London

A Facebook group set up by a local young (18y/o) Labour activist in the London Borough of Merton.

Definitely a majority of volunteers are women, there is a good mixture across the borough of community groups, ethnic groups and faith organisations. Probably more likely to exclude people without the ability or access to platform technology.

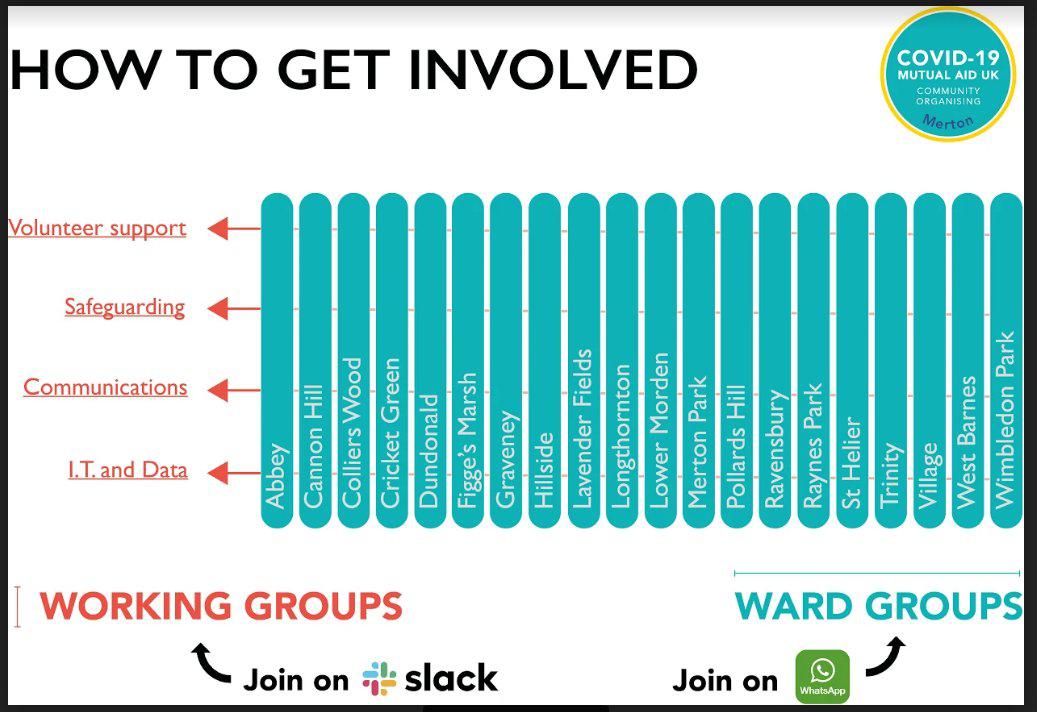

A number of WhatsApp ward groups were established. The WhatsApp groups are joined through links on the Facebook page (gaining over 2000 members in 3 weeks) and through a website created to steer volunteers to their local area. Airtable was used to gather (limited) data on location and resources such as cars/printers. Slack working groups have been set up to allow those who are interested to participate in decision making, developing website, social media, and strategy.

The assistance has been primarily local deliveries of shopping, so people organise their ward to make sure as many streets as possible can have leaflets delivered with volunteers’ names and numbers written on them. The website has also allowed people to request help by filling out a form leading to them being put in touch with a volunteer.

The main challenge has been trying to encourage autonomy of local groups when so many well-meaning individuals have an internalised understanding of managerial structures. Decision-making has tended to be haphazard and usually made by people who became involved earlier or who have admin privileges on platforms such as Facebook, WhatsApp, Google, Slack.

We’ve also had a lot of discussion about safeguarding guidance. Some people assumed that the group had a legal imperative to provide guidance and ensure volunteers followed it, whereas others tried to reinforce how the localised, trust-based structure does not require the same approach as a charity, and that without a legal form, we would be unwise to present ourselves as a formal organisation because it will create an impression of certain protections (DBS checks, training etc). In summary the main challenges have been around ‘Central vs. Local’ or ‘Charity vs. Solidarity’.

Relations with pre-existing voluntary and charitable groups have been generally good, the council volunteer service has engaged with the group and been constructive. Local food banks, etc, have collaborated effectively and welcomed the help of mutual aid volunteers.

Politicians have either: operated in own silos and been uninterested in borough-wide cooperation; actively criticised the group for not being ‘professional’ enough and encouraged people to ignore it; or, after initially being quite active, retreated completely into inaction.

Power dynamics created by platform admin rights have caused some disagreement, as some complaints have arisen from people rightly reacting to being told what to do. There was a complaint about the network becoming politically motivated and acting as a front for the Labour Party.

Usually conflicts have been resolved in a managerial manner by self-appointed experts, although

there has been transparency about potential learning which was shared with local group coordinators.

‘Neighbours helping neighbours’ has become the most resonant refrain of volunteers and it sums up the purpose of the group quite accurately.

Man, Greater London

We started an open WhatsApp group, which was advertised on Facebook. We cover Herne Hill, Dulwich Village & bits of Brixton.

The organisers appear to consist solely of individuals (i.e. no pre-existing political groups). We’ve never openly discussed our personal politics, but we appear to be broadly on the same page when it comes to important issues like autonomy and people’s privacy.

The GPs’ surgeries and Age UK have given lots of people our details. We flyered pretty much the whole area, to make sure that non-computer users are aware, but we’re worried about people with English as a second or other language.

Requests for help and offers of help are submitted via a basic website we built (or phone). Organisers communicate by email and WhatsApp, and we’ve also organised into smaller street groups, which have their own communication preferences. Organisers take it in shifts to process requests, passing them on to street groups or sorting them directly, and checking difficult things with all of the other organisers. We have two admin-only broadcast lists on WhatsApp because the main group got too full and a bit busy.

Initially we mainly did shopping and prescriptions. But then two things happened: we got an incredible response to a speculative call for occasional food donations; and the food bank network basically stopped working because it became overwhelmed. The council hasn’t sorted out its own emergency food system. So, we are now distributing food directly to people who ask.

We’ve been unsure about how to handle requests for help where there should be formal state assistance - e.g. adults with care needs. It’s difficult to offer practical solidarity (and ensure dignity) without allowing the state to abandon its duties, and undermining care workers.

Residents’ Associations have been worse than useless. Charities have referred a lot of people to us. The council sometimes rings up to find out what we’re doing.

The local councillors have been generally benign, but they’ve tried to use the WhatsApp group to promote council updates etc. It was kind-of great to watch them get shouted down and challenged, but now we’re insisting on vetting all their posts.

There don’t seem to have been any open tensions in the group. But it’s difficult to know what everyone thinks of each other.

We’ve adopted and promoted documents from groups like QueerCare to explain the principles of mutual aid. Our WhatsApp group description has a basic explanation that we’re non-hierarchical and inclusive.

Woman, Greater London

I joined the Tower Hamlets Mutual Aid Facebook group from the lists going around on social media early on in the pandemic. From there, admins set up WhatsApp groups which splintered into different areas (with the same admin). It’s been in the hands of one or two local people from the start. Mutual aid admin is very much a case of who is first out the door.

The mutual aid group covered Tower Hamlets. WhatsApp groups segmented to Bethnal Green, then the immediate area and now I’m mainly using one restricted to my building which houses several hundred people, but the membership is very small. The Facebook group is still borough wide. It tends to be the same few people posting on WhatsApp. Given how much of it is over WhatsApp messages, you can’t really call it on who is who or anything about their background. Anyone without the digital skills or access to a smartphone/computer is shut out from mutual aid conversations. We have recently created an arrestee support on Signal.

We have assisted with shopping, picking up stuff from the chemist, signposting, and general advice. Since the pandemic has eased up a bit and with the increased activity from Black Lives Matter, we’ve seen the Facebook group increasingly being used for sharing petitions and fundraisers and campaigns. This is a very good sign of how the group might develop into a general local activism hub in future.

Mutual aid groups, by their nature, attract bored people with something to get off their chests. So we’ve had issues with curtain twitchers, racists, Tories and people who want to bureaucratise everything (e.g. DBS checks for volunteers).

Overall, the biggest problem is the admin. All requests for help are directed upwards to what I think is two people and handled from there. We don’t really get a sense of what is going on in the group and how people are helped. The WhatsApp can get spammed with soft spam ‘free yoga classes’ that don’t necessarily qualify as mutual aid.

Members less experienced in organising have a lot of enthusiasm that can burn out – it’s up to more experienced people to find ways to keep that momentum going. I’m very big on following up any request (help this person/sign this petition) with a result, sharing what was achieved. This is hard with central mutual aid activity because it is so hidden in our group but with political stuff it is easier, and it fosters a sense of ‘getting the job done.’ Some people do come in with 300 ideas and try to reinvent the wheel so it’s all about making pre-existing paths and services more visible. There are many, many very basic services provided by the council that people had no idea about.

Woman, Greater London

I wanted to highlight how difficult organising within our group has been. There have been many, many conversations about ‘not making this political’ despite the very obvious political nature of what we’re doing and of the current situation, and a real struggle to stop it from turning into neighbourhood watch. This is less of an issue now, several months in, but to begin with there were lots and lots of people suggesting that we call the police on those breaking lockdown for example.

After a very big argument in which somebody said they felt as if they’d ‘accidentally joined an antifa chat’ (!), a separate group was set up to enable political conversations/education, but this hasn’t been without problems either. There are obviously disagreements in there too based on people’s political affiliations, and because a lot of people are stressed, tired, anxious etc and the conversations are all online, it has often descended into bickering or arguments, misreadings of tone and so on.

That group is also much less practical – there’s no actual mutual aid going on, it’s just political conversations between neighbours who mostly agree on everything. I’m very glad to have met some of them and to know there are comrades on my road/in my area, but it’s been quite frustrating overall.

I know that other groups have had admins who have been both more proactive and clearer about the political nature of mutual aid, removing people from chats who have said they’re going to call cops etc and I feel I would have got a lot more out of that.

On the plus side, I do know a lot more people in our community now as we only moved here a month or so before this all started, and I do see that as a basis for more local organising especially if the branch and constituency Labour Party start to move rightwards.

Man, Greater London

The Croydon Mutual Aid group was assembled in mid-March by local organisers – a few of them had small businesses. Almost immediately, it became incorporated into the network of charities called Croydon Voluntary Action and then to the Croydon Council – so it had largely stopped being a ‘mutual aid’ group, and became an expansion of the charity networks and a space where the council became directly involved. Within a month, they asked for details of the volunteers – name, address, whether they had a DBS, etc, so that they could be on some registry. By that point, I stopped being involved, partially because I didn’t have a DBS on hand. I don’t think that members of the group had a very firm understanding of mutual aid as they kept signposting people to the councillors. But I guess expecting people to spontaneously come to that understanding, while also observing how readily the council got involved is, to be honest, quite an ask. Whatever understanding of work relations that people have gained since the crisis, has been very limited in my opinion. I don’t think that there’s been the space for people to communicate these issues or think about them too much.

Man, South-East England

Mutual aid groups helping communities cope with the Covid crisis have been all the more inspiring for having been organised in the wake of 40 years of state-imposed competition. Unfortunately, that hasn’t meant that the logics of that hegemonic ideology have been absent from the practice of mutual aid.

In one of my own mutual aid groups, a small, unelected vanguard of professionals and aspiring technocrats put themselves in charge, despite the presence in these organisations of many people with much greater experience and understanding of the theory and practice of mutual aid. These self-appointed “directors” then began collating data and introducing statistics-based competition – actually existing neoliberalism – in the belief that this would persuade people to do more good. It didn’t occur to them that this would also create a lot of failure. Grimly resisting any sort of democratic oversight, they were finally persuaded to acquiesce to at least some level of accountability in the form of a survey agreed with and sent out to group members, and a series of conference calls about the future of the group (people who are active in trade unions that represent education workers may recognise the use of surveys as an effective tool when dealing with recalcitrant senior management teams). The general consensus was that the group should continue along the lines of principles broadly in line with those of mutual aid in its original, intended sense.

There have also been a number of instances of group members wanting to involve the police in certain issues (a police employee was specifically asked to join the group) and generally professionalise the group. Sometimes – for example when linked to concerns around safeguarding – this has been borne of genuine (if misguided) concern, even if it has also spoken to a certain pessimism and misanthropy. At other times, it has been borne out of outright racism, for example when a member boasted of having informed the police about a traveller group that had recently settled nearby (the member was later persuaded to apologise by left-leaning members). This kind of authoritarianism – particularly in the interests of private property – arguably resonates with both of the dominant ideological post-war programmes (social democracy and neoliberalism) and potentially with the next one – that of post-democratic Keynesianism.

Subtle attempts have been made to establish further, less formal hierarchies. Good ideas from less prominent participants have been ignored or disdained, then later repurposed by influential cliques. At one point, my partner suggested starting a clothes bank. She was immediately inundated with passive-aggressive replies from older women, telling her that “it is not the place of this group to debate this sort of thing”. This kind of interaction between women brings to mind Kimberlé Crenshaw’s theory of ‘the stack’, in which women, trapped in a metaphorical basement thanks to the oppression of patriarchy, end up pushing one another down in their attempts to climb out through the trapdoor.

What this all seems to speak to is an internalised notion of the “good Samaritan” recognisable in Margaret Thatcher’s understanding of and purported enthusiasm for charity, through which the privileged are able to discern and police who is deserving of aid and who isn’t.

Those most likely to exhibit behaviours associated with neoliberalism have most typically been those who have backgrounds in professions linked to finance capital, those who hold managerial roles that involve disciplining public sector workers, or those public sector workers who are used to being disciplined by the aforementioned class and have internalised its practices.

Those who seem the least susceptible to these attitudes and mores tend to be millennials. A feature of the whole Covid moment has been the flow of aid from young to old and the greater willingness of the young to make sacrifices in the interests of social solidarity. I wonder if an explanation for this might be that boomers who are still working may have spent the entire neoliberal epoch in the labour market. It is therefore reasonable to speculate that they may have internalised its logic more than any other group. Those of us born during the neoliberal era have spent significant chunks of that time in full time education, where we have most likely been insulated, at least partially, from its excesses.

It is important to add, here, that the experience of mutual aid has ultimately been a positive one that has inspired hope. It has certainly underlined my conviction that the desire to be cooperative, to be collaborative, to be sociable are common to most people. But the ways in which we have been conditioned to think and behave have, it seems, had a deep and pernicious influence on how we actualise these desires.

Man, Greater London

I was involved in the Croydon mutual aid group from close to the beginning of the pandemic, and had a pretty positive experience overall – at a time when things felt very uncertain, and after a long time involved in the slow and patient (and boring) work of being within the Labour Party, it felt good to be doing something with tangible consequences. Perhaps some of this enthusiasm was misplaced, but it did feel like we were directly involved in shaping our surroundings – the questions which we encountered were the sorts of questions you would have expected to encounter in trying to fill the vacuum of the state, and that was exciting.

Many of the people involved in founding the group were Labour Party members, but that generally seemed incidental – it was wonderful to be able to do political work (and it definitely was political!) with people without factional considerations becoming prominent. Rather than attempting to take over the mutual aid groups, I think most of the Labour members involved put their party membership to one side – but still brought across skills which were gained there. I remember commenting that Labour members were well-prepared for mutual aid because we’re used to being in so many WhatsApp groups! One difference though: mutual aiders took to Slack much quicker and more keenly than anyone in the Labour Party ever did. For my part, involved in mapping the mutual aid groups in the borough, I was also able to bring across something more ‘material’ – the ward boundaries which we used as a layer on Google Maps were taken from a Labour canvassing rounds map.

This experience has caused me to reflect on how I approach the Labour Party – sometimes it’s less about what we can achieve within the party, or what we can use the party for, and more about the sorts of skills and resources which we can break out of it. On the other hand, it’s also caused me to reflect more on some of the limitations in operating within the party – whereas Labour members involved in mutual aid were quite creative and energetic in their response to the crisis, as soon as we stepped back into the (virtual) CLP meeting, it felt like members there were more focused on the sorts of requests which could be made of politicians. Mutual aid shows us that isn’t all we have to limit ourselves to.