EDITION: Bad New Times.

Socialist transfeminist proposals offer a challenge to the ever-increasing backlash against trans people.

Entering the new decade, the left in Labour has faced a situation determined by significant, perhaps terminal events: not only the General Election defeat of 2019 but the election of Keir Starmer as Labour leader. Recent months have also seen the leaking of a report which revealed senior Labour officials attempting (successfully) to undermine and sabotage their own party, including abhorrent cases of racism and sexism towards Labour MPs. In response, Starmer appoints Paul Ovenden, one of those named in the report, as deputy director of communications. Alongside these defeats, there is, of course, the current global pandemic. It is clear that there is an urgent need to re-think and re-assess our strategies and theoretical outputs in the coming years, this reassessment is especially vital with regards to trans liberation.

In Britain already, the situation is characterised by an ever-increasing backlash against trans lives, following years and years of unprecedented media hostility towards trans people from both left and right-wing outlets. This has led to an 81% rise in reported hate crimes against trans people in 2018/19. The global pandemic has made gender-affirming healthcare even more precarious. Waiting lists for a first appointment were already up to 166 weeks and now Gender Identity Clinics (GICs) are advising GPs (in what could easily be considered medical malpractice) that temporary reductions or stoppages in hormone prescriptions are nothing to worry about. Trans people face a spectrum ranging from ignorance to outright hostility, and in the face of this the left in Britain has a responsibility to uphold and listen to trans voices, as well as provide a solidarity that goes beyond mere recognition to more direct, concrete forms of action. We are living in turbulent, unprecedented times, and for those of us working towards a socialist, transfeminist future, solidarity is more important than ever in this new decade. For the left, this future requires an understanding of solidarity as not just mere sloganeering, but as the hard, unglamorous work of effectively combating and eliminating transphobia and transmisogyny within our movements. Sadly, in the years since I wrote about the numerous cases of such behaviours on the British left and in trade union movements, attitudes and responses have remained mostly the same and, at certain points, have become even more hostile.

Looking back, looking now. What is to be done with trans people?

Two years ago, when writing about the numerous cases of transphobia and transmisogyny in the British left and in trade union spaces, I hoped that these would be tendencies that would reduce over time, that the British left would listen and understand that fighting against working class trans voices would do nothing but hinder efforts to develop anything better than an already stagnant and near non-existent left-wing response to the interlocking crisises in contemportary Britain. Instead, transphobic attitudes, from the subtle to the explicit, have been allowed to continue openly with very little in the way of disciplinary procedures or a genuine desire to crack down on transphobia and transmisogyny. This problem is endemic, whether in the Labour Party, anti-fascist organising, far-left groups or parties, trade unions or left media.

Just before the 2019 election, it was revealed that the ‘culture war’ on trans rights was a core Tory tactic to try and influence voters in working class areas. Despite this gruesome tactic being made clear, most of the organised left failed to directly confront this and other transphobic attitudes. Consequently, the transphobic themes of the Tory culture war remain unchallenged, with predictable consequences both electorally and for trans people’s lives. This includes (during Pride month) the scrapping of any plans to reform the Gender Recognition Act, despite public consultations showcasing 70% of respondents supporting reform. Essentially, a timid electoralism involving appeasing ‘The Working Class’, identified with Leave voting and a range of regressive attitudes, gave space for and to revitalised (and very middle class) Labour right saboteurs and an attendant political culture with very little to say about the realities of working class people, trans or otherwise. This cowardice and ineptitude is further evident in Starmer’s ambivalent attitudes towards the GRA and trans rights.

Persistent transphobia and transmisogyny extends beyond the Labour Party, an incident in 2019 with the anti-fascist football group, FLAF (Football Lads and Lasses Against Fascism) and their main Twitter account, involved an admin (in now deleted tweets) encouraging a dog-pile on Devon Rape Crisis, for simply specifying in advertising volunteers that they were looking for self-identifying women. Upsetting as this case is, at the very least this incident did produce a significant and necessary call of solidarity online from anti-fascist groups all over Britain against transphobia. Rogue admin or not, all it can take is one person in any left-wing or anti-fascist space, to make a group seem dangerous and alienating for working class trans people . In a more recent case within trade unions, LGBT+ representatives in the National Education Union (NEU) have been overruled to allow known transphobe Debbie Hayton to run for LGBT+ officer in the TUC. Again, all it takes is one person with hostile, transphobic views to make things dangerous and unsafe for trans people.

Clear, distinct disciplinary procedures are needed in any serious institution and denying the scope of transphobia and transmisogyny in British left-wing culture means these calls for solidarity end up having less of an impact. Just less than a year ago, youth organising officers in the Young Communist League (YCL) were threatening women (myself included) for challenging transphobic members and the group’s association with both the Morning Star (one of the worst culprits in the trans ‘moral panic’ ) and their associated party, the CPB (whose members include Mary Davis, who advocates explicitly transmisogynist motions for the party ). Yet now in 2020, there is a persistent denial of these attitudes, with the YCL even claiming to stand for trans liberation without any transparency on whether transphobic members have been disciplined or expelled (hint: they haven’t). Deleted posts from YCL show that their support for trans liberation is false, with the Scottish branch praising transmisogynists at Edinburgh Pride in now deleted posts.

These evasive tactics from certain left-wing and anti-fascist groups showcase an awareness that explicit transphobia and transmisogyny are indeed despicable, unacceptable attitudes. There is a growing awareness that such open attitudes can no longer be tolerated. However, many in the British left promote a faux sense of solidarity coupled with and often underpinned by active denial (deleting posts with no explanation) of their own continuous cases of transphobia, for recruitment purposes and essentially to make these (youth) groups ‘look good.’ I should stress that I don’t want this piece to be a repeat of what I wrote in 2018. However, we have to highlight the reality that there has been next to no improvement from the British left, including far-left and anti-fascist spaces and publications, on combatting transphobic, transmisogynist attitudes, alongside the further systemic issues of gendered violence.

Despite the numerous mobilisations for gay and lesbian rights in the previous decades, from tens of thousands in Manchester against Section 28 to lesbians abseiling Parliament, the acknowledgement of how radical this was at the time and therefore the appropriate legacies in Britain are more or less gone in the public memory. As Juliet Jacques says, transphobia is everywhere in Britain now, a ‘respectable bigotry.’ The celebrated workers histories and legacies of lesbian and gay solidarity have not been reproduced for trans people, even in these pressing times. If anything, ‘trans liberation’ has become a trivialising matter, if it’s not outright bigotry that we face, it’s mocking the ‘trans question’ as frivolous and not part of a strategy for ‘genuine’ working class organising. Then, when this transphobia affects recruitment (especially for the aforementioned groups), we get a post or two supporting trans people, all the while the openly transphobic senior members are never disciplined. The incredibly middle class nature of transphobia, from senior trade union members to university lecturers was evident back in 2018, and the basis within the ‘labour movement,’ for transphobia still appears to be most substantial in the most middle class unions: among teachers, lecturers and other relatively senior public sector workers.

There are then contradictions in questions around class and the affirmation of trans rights, and these contradictions effectively silence trans working class people within the dominant mainstream, including the dominant mainstream of the left. On the one hand, transphobia as a ‘respectable bigotry’, its labour movement basis in the most middle-class unions and the moral panic generated significantly by newspapers like the Times or Guardian. On the other, the persistence of a nostalgic white machismo and wider set of stereotypes about working class people, that posits ‘The Working Class’ with a capital W as lumpen, monolithic and regressive. Despite the existence of trans working class people, the concerns of trans people are held to be out of touch with ‘The Working Class’. As long as these conceptions, which are strongly institutionalised, and the tactics grounded in them go unchallenged, the British left will continue to be at a standstill. However, despite everything, it is through these conditions that trans people themselves have produced the necessary theoretical contributions that we as socialists must consider.

Transfeminist proposals for the future.

Out of the hellscape of such normalised and rampant transphobia and transmisogyny, the burden falls on ourselves as trans people to effectively organise ourselves and develop new theoretical approaches and practice that can build the socialist, transfeminist future that we desire. We have had no choice but to make our own theoretical contributions and analyses in these current situations.

Following the 2019 election, the Labour Campaign for Trans Rights was established as a group, with a published manifesto and coverage in Labour-related publications. One pledge in particular, caught the attention of transphobic Labour members, pledge 10 “supports the expulsion from the Labour Party of those who express bigoted, transphobic views.” Whilst this is a sensible pledge – and one that represents nothing more than a demand that the Labour Party Rulebook, be enforced, even this most moderate of proposals from trans voices in left-wing spaces resulted in a hashtag on social media of numerous ‘Labour’ members showing their disgust at the demand that bigotry should not be tolerated in their own party. Torr Robinson’s accompanying piece in Tribune discusses the goals of trans liberation and the strategies needed to achieve this goal. Robinson is right to point out that trans liberation “require[s] structures and organisations that we can utilise to empower us and carry the fight beyond individuals and even through generations.” This suggestion is further expanded, with Robinson arguing that the mobilising and organising capacities for this can and should be formed mostly through the Labour Party, “Labour has the social depth and organisational scale to both build alliances amongst oppressed people and challenge the powerful.”

Despite acknowledging that Labour has a history of “manag[ing] away marginalised groups when inconvenient,” Robinson’s proposals for trans liberation now feel like they come from a period when we could invest more hope in Labour, before the election of Starmer — (the leadership candidate who refused to sign up to the pledges) — as leader, before what that choice revealed about the membership, before the revelations of the leaked report and before the leadership’s unwillingness to address the institutionalised racism and wider discrimination discolosed. December 12th and what has happened subsequently may well suggest the necessity for a turning of focus away from Labour.

In challenging Labour-centric base building elsewhere, Carson Rainham’s essay in The Lever proposes a base building that understands the need to move beyond Labour and towards a genuine proletarian, class conscious culture that strives for socialism. In critiquing Marcus Barnett’s own piece on base building (also in Tribune), Rainham agrees with Barnett on the necessity of a red base building movement in Britain, but argues that a project like that proposed by Barnett that romanticises previous Labour-centric working class institutions, fails to consider the much needed work that socialists must undertake:

It is incorrect to believe that people will become convinced Labour Party socialists when you turn up at the door a decade too late to set up a pub, gym or men’s choir with socialist characteristics. It belittles the struggle for socialism, a class struggle, to one between the ways in which people relate to one another instead of how they relate to the means of production. Giving people more to do in the community might mitigate social unrest and alienation but it does not improve their labour relations or help the class to achieve political power. And from experience, more pubs (socialist or otherwise) does not equal more opportunities for a movement to grow.

Socialist, transfeminist approaches can and must be a part of a new red base building project in Britain, one that feels more crucial than ever right now, one that ignores the ahistorical conception of ‘The Working Class’ fuelled by (white) nostalgia and recognises the true, direct needs of workers and oppressed people. However, with a non-existent presence in public life, those building socialist institutions must analyse and work alongside workers and oppressed peoples to consider the base building that is necessary for us to build and develop a new class consciousness, as seen (and acknowledged by Rainham) by (generally trans-inclusive) organising in what can be described as the tendency of New Social Strikers and Grassroots Unionists/Infrastructuralists that compose the fragmented state of the British radical left and trade union movements.

All of this considered, it is evident that promoting the necessity of Labour to socialist mobilisations in general and socialist transfeminist ones in particular can already feel dated, even in the short space of time between the launch of the Labour Campaign for Trans Rights and today. However, despite the apparent bleakness of the landscape, there have been significant theoretical innovations in Marxist transfeminist theoretical work.

Harry Josephine Giles’s recent piece on ‘Wages for Transition’ has, from the title alone, a clear influence from the works from Wages for Housework and the autonomist feminism of Silvia Federici and Mariarosa Dalla Costa (all of whom are acknowledged by Giles). Giles’s approach focuses on the works developed by these groups and authors, as well as drawing on Amy Cohn’s “Wages for Advocacy”, which considered the unpaid labour in trans advocacy work. Giles then extends the arguments for wages for housework and wages for advocacy by arguing that gender and transition itself is a form of unwaged work and that Cohn’s focus on the unpaid labour in trans advocacy work should be broadened to showcase the entire process of transition, from the workplace to interactions with GICs, from taking hormones to watching and learning videos on gender expression and presentation as forms of gender production that are unpaid labour.

Our care work is unpaid. Our medical expertise is unpaid. Our gender production is unpaid. Our advocacy is unpaid. Our training is unpaid. Our support work is unpaid. Our teaching is unpaid. Our writing is unpaid. We are in poverty. And so now, at the very point at which our genders are beginning to be renaturalised by liberal capitalism, as the state offers a pittance of funding to our healthcare needs, we demand not merely free healthcare, not merely a place at work, not merely a reparation settlement: we demand wages for transition.

Our voices on our own productions of gender and the labours we produce elsewhere in the life-giving processes under capitalism can all be considered as forms of social reproduction. To reproduce not only ourselves, but also others in our own spaces and communities, from support groups to chosen families, Giles’s approach here considers all this the work of gender production, a decolonial, disabled and neurodivergent demand that is “Wages for Transition.”

Another major piece of work takes the form of a journal. The launch of Invert Journal has been significant in providing various approaches to, as they describe themselves as, “a journal of contemporary Marxist thought focused on the abolition of gender and the liberation of feminised subjects.” This emphasis on gender abolition and a Marxism of the feminised, primarily from a UK context, provides a significant case study into the new and emerging transfeminist ideas that are being produced here. In the editorial for the journal, themes of gender abolition are considered with the contextual awareness that terms and ideas such as “gender abolition” have

largely become the conceptual terrain of the transphobic right wing of feminism. Here, the critique of gender—however foreshortened—put forward in the radical feminist movement of the 1970s, has devolved into its opposite: the affirmation of gender through the affirmation of its concrete and naturalised pole—the category of sex.

In reality, the editorial rightly points out that these positions “equate to little more than the abolition of trans people.” Invert Journal’s proposal on gender abolition therefore suggests:

By contrast, we conceive of gender as a social form comprising both abstract processes and concrete manifestations, thought through the categories of gender and sex respectively. Following Endnotes, “for us [too], sex is the naturalisation of gender’s dual projection upon bodies, aggregating biological differences into discrete naturalised semblances.” As such, we understand any project which aims at the abolition of gender without also bringing the category of sex into its movement of negation, as constituting a foreshortened critique of gender, doomed to not only failure but reactionary corruption.

It is important therefore that future proposals to abolish gender require a criticism and awareness that even the (biological) category of sex itself is within the sphere of social construction alongside gender and, in this case, sex provides a justification for the naturalisation of gender. Socialist, transfeminist ideas in Invert Journal are noticeable in the examinations of a Marxism of the feminised:

Feminisation is a process, but not a fluid one, as the radical queer approach to gender-ing or queer-ing has often thought. It has definite results that can be traced; it refers to a moving fixedness, changing according to historical conditions, limited always by the vicissitudes of capital. Understood as a process of immiseration, feminisation can therefore be treated as an expansive category, “defined by but not confined to the category of ‘women’”. Our demand, then, is not one which isolates a core of individuals we wish to see liberated, but liberates society from the process of feminisation.

Transfeminist approaches to Marxism are refreshing to see, especially from a UK perspective, where years of hostility, even on the left, in our lives has felt omnipresent. Also forthcoming (in March 2021) is Pluto Press’s anthology Transgender Marxism edited by Jules Joanne Gleeson and Elle O’Rourke, further broadening the much needed discussions on trans liberation from a Marxist perspective. These examples alone showcase both the growing need for Marxist, transfeminist proposals in Britain and elsewhere and that this need is beginning to be met and is a sign of the changing circumstances in trans liberation. However, times have changed incredibly even since the published pieces referred to here were written. Therefore, as socialists, we have to be prepared and consider the transfeminist, post-pandemic world that awaits us.

What is the future? Post-pandemic proposals for a socialist, transfeminist future

This pandemic will change everything and we cannot fully know the scopes of these changes. What are potential post-pandemic responses for a socialist, transfeminist future? After the revelations of the scopes of sabotage and undermining grassroots organising in Labour what will be possible within and outside the Party? After years and years of what seems like a never-ending moral panic for trans people what can be done? There can’t be any definitive answers to these questions. But there is still a scope of considerations and proposals that will be addressed here. If there is anything that we can do, it is recognise and challenge an emergent trans liberalism that has shaped a significant amount of trans activism in Britain and elsewhere in the imperial core.

Trans liberalism encompasses various forms of activism that as such can have real, well-meaning goals of improving and transforming trans lives, but much like previous activism surrounding marriage equality, is ultimately underpinned by sticking to the essential terms of the status quo. Trans liberalism is the palatable voice, occasionally filtered through with some left-leaning mottos and language. Trans liberalism can still be well-meaning, but it’s important to recognise how it tends to focus on reducing our struggles into either gender recognition reform or ‘reduced waiting lists.’ This current pandemic is pushing our health services to the limit due to a decade of austerity, underfunding, underpayment and with it the consequent shortage of NHS workers. In the context of a likely harsh austerity response in the wake of the crisis, it is likely that trans healthcare, already woefully inadequate, will suffer even more. A trans liberal response may well end up in a defensive posture, trying merely to defend this inadequate status quo (166 week waiting lists), or at best in a continued call for shorter waiting lists. Post-pandemic responses, however, have to recognise that passive notions of ‘shorter’ waiting lists are no longer sufficient, NO waiting lists and an informed consent model should be the norm even in trans liberal spaces.

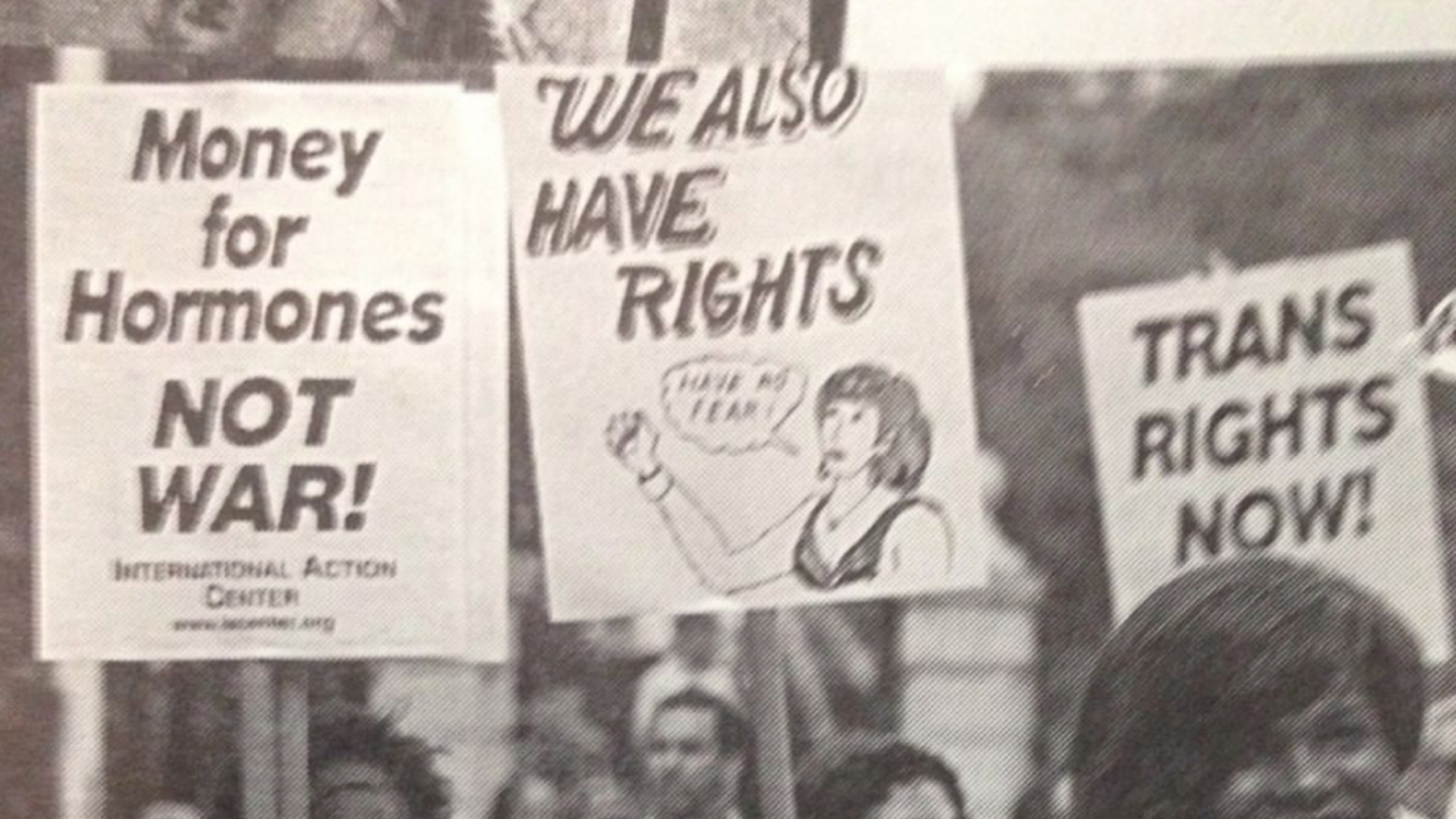

Trans liberalism does not only represent a set of broadly technocratic, conformist political responses, its aesthetics and slogans have become a focus point for me personally. Aesthetics and sloganeering in trans liberal events and protests carry the consequences of potentially trivialising trans narratives, diluting and undermining the real and dangerous situations that we are witnessing now and most certainly will continue to face in the future. Moreover, these aesthetics go hand in hand with the reinforcement of the abysmal and effectively useless “defiant whimsy” that is British protest culture. Trans liberation will never happen under the status quo, but gendered divisions of labour and the life-making processes that are the driving force of capitalism can rely on trans liberalism. Trans liberalism ends up ensuring that, at best, mild reforms for our lives happen (usually legal instead of material and urgent, such as in employment, housing and healthcare) and, at worst, the situations only continues to get worse, as so-called ‘leaders’ on trans rights, continue to ask us to do another petition or gaming stream for pro-police, cis-led groups whose support for us is all but conditional.

Trans_Liberalism.jpg

In JJ Gleeson’s piece in Invert Journal, Gleeson uses a key example of trans liberal sloganeering, the phrase “trans women are women, trans men are men.” Gleeson posits that this motto with the consideration that trans liberal activism’s end goal of state recognition “will always be fraught, and provided unreliably.” Because of this, this popular motto in trans liberal spaces carries “a double edge”:

With ignorance about trans lives so pervasive and widespread, it can be tempting to provide a straightforward line around which a serious number of people can be expected to rally.

But there is a risk in providing “a simple answer to a complex question”, especially as a defensive move in the context of battling phobias. Do we really want to boil our lives down into a form that makes them appealing to, and appreciable by, the state?’

Trans liberalism tries to offer simple answers to complex questions, well-meaning in trying to get potential allies to understand trans lives. But understanding the state of trans healthcare, through personal or collective perspectives will never be a simple answer. Transfeminist proposals are complex. Lola Olufemi’s suggestion that feminism is ‘a framework with “no coherence, or consensus,” stands true even within transfeminist discussions, between cis allies, trans liberals and even amongst fellow transfeminists. There will never be a universal experience of trans liberation. In order to move past these simple mottos based on consistent reminders that yes, our lives are ‘valid,’ Gleeson’s advice is to instead “bring the complexity of our lives back into view.” Our lives are complex and incredibly varied, trans liberal slogans such as ‘Trans Rights are Human Rights’ are an obvious truth, but only a starting point as to the full picture of our complex lives. We need jobs, housing, healthcare and an end to racialised, patriarchal capitalist oppression and the need for a post-pandemic response that is transfeminist and socialist in nature, becomes even more crucial.

Conclusion

As I’m writing this, Liz Truss, the current Minister of Women and Equalities has proposed plans to restrict gender-affirming healthcare for trans youth. Her speech uses foreboding language, of ‘checks and balances’ on trans people’s ability to live our own lives, questioning the capacity for trans youth to access their own (limited) healthcare and contains an insistence on protecting ‘single-sex’ spaces. Meanwhile, a High Court inquiry is currently underway against the only GIC for trans youth, with the potential consequences of further restricting gender-affirming healthcare. Every new draft or edit for this article has involved in some way adding another instance of transphobia. Every ‘left-wing’ transphobe is on the side of this, the side of the Tories (and every left-wing transphobe gets a sympathetic write-up in the right-wing press and a right-wing millionaire gets a sympathetic write-up in the so-called ‘left-wing’ press of the Morning Star). They are on the same side of far-right, fascism in Hungary, taking advantage of a pandemic to outlaw legal gender recognition alongside the far-right in Poland legislating the ‘family card,’ effectively making the whole country a so-called ‘LGBT-free zone’ and ‘[p]rohibiting ‘propagation of the LGBT ideology’ in the public spaces.’

“Which side are you on?” This question feels more pertinent than ever before, now more than ever and for the future, we need to be looking after each other, alongside building support networks and organisations that can and will provide the base building power necessary to fight back against the upcoming battles ahead of us.