EDITION: 5th Birthday.

The grown-ups are back in the room: it's time to put all those silly hopes and dreams away.

Centrism is the non-fascist suppression of politics. In The Apprentice’s Sorcerer, Ishay Landa notes that, in the early 20th century, when democracy threatened private property, many liberals threw their lot in with fascism “in order to salvage the vessel of capitalism.”1 But while fascism can be an ally of economic liberalism, it is, as Landa points out, “a bullying, patronising one”2. To contemporary defenders of the rights and disciplines of property against the effects of the popular masses, centrism offers a far more convenient means of suppressing politics than fascism’s hyperpoliticisation against politics – and fascism has a bad reputation nowadays.

To that end, we now find an array of hacks, from across the ‘sensible’ spectrum of opinion, in celebratory mode. The grown-ups are back in charge, they write, jubiliantly. “After a bizarre period of politics, it does look as if a grown-up is back in the building”. The image of “the grown-ups” repeats endlessly. Adorno once wrote that “[Marcel] Proust… did not go along with the renunciation of responsiveness, nor with the false maturity of resignation. He kept faith with the childhood potential for unimpaired experience and, with all the reflectiveness and awareness of an adult, perceived the world in as undeformed a manner as the day it was created”.3 Proust saw endless possibility, with the vision of one whose world has not yet been limited. Centrism—putting the grown ups back in charge—is that enforced false maturity of resignation.

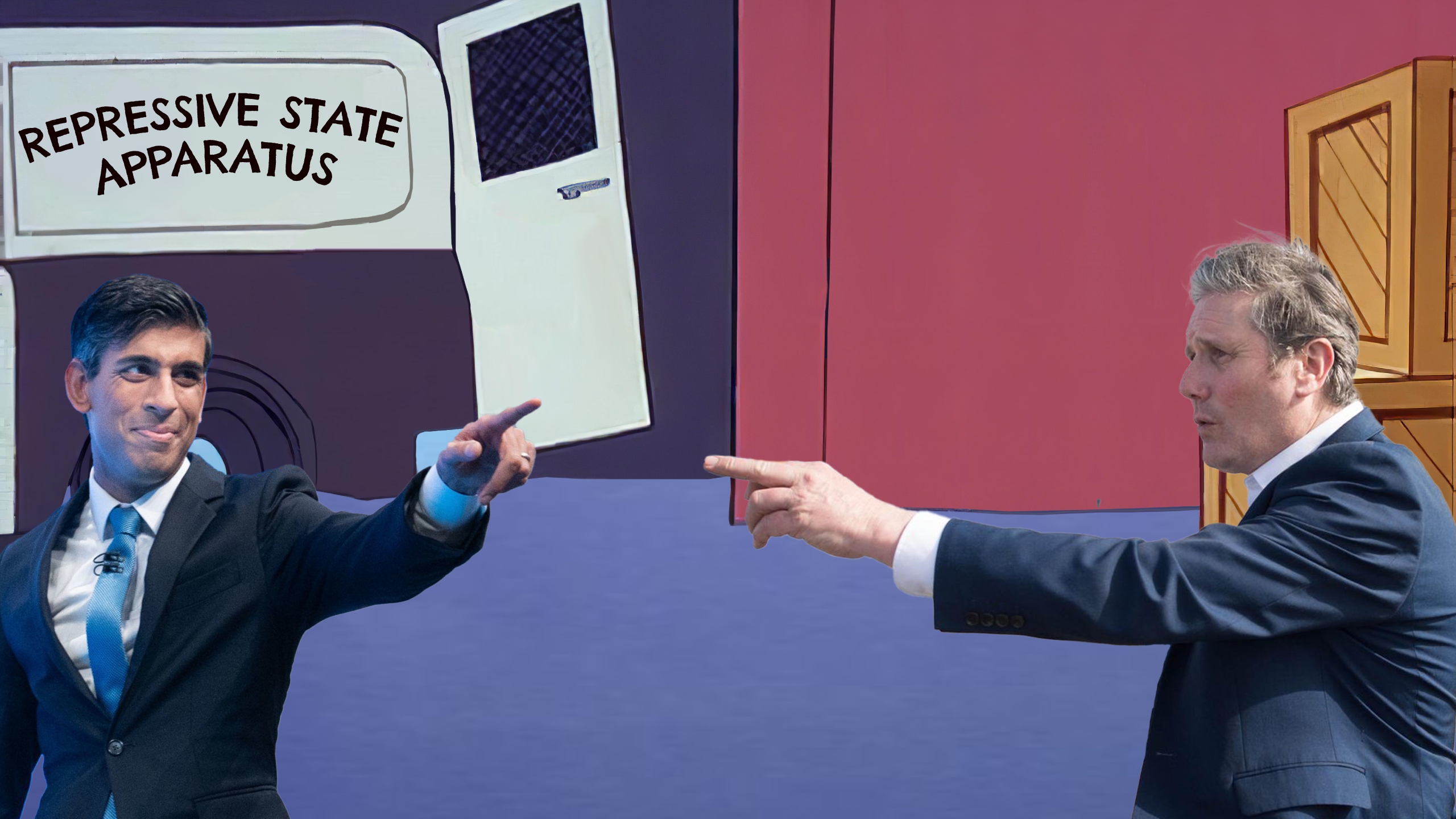

“The grown ups,” plural. Centrism is not primarily an electoral strategy, but a logic above that. (Best not to risk elections really mattering: that might lead to “a bizarre period of politics”.) In its ideal form, centrism is a pair. Not Sunak, not Starmer, but Sunak-Starmer. To paraphrase Julius Nyerere’s quip about the USA, the centrist vision of Britain is a one-party state where, with typical British politeness, they have two of them. The ideal of smooth transitions of power, from one to another, with minimal disruption. This tells us something about the limits of calls from the left calls a General Election. Whilst the centrist dyad persists, calling for a legitimate transfer of power tends to legitimate its logic: the non-antagonistic contradictions, the suppression of politics, all wrapped up in the transfer of power between two responsible, consenting adults.

Corbyn, and the endlessly infantilised movement, refused the false maturity of resignation. We refused to give up on our desire. We maintained at least some sense that things could be different, some sense of the possibility of a world “as undeformed as the day it was created”. The story of Corbynism was an epic of the hope that we might make our own history. The last great – and, significantly, the last funny — moment of the Corbyn epic was the ominous caution that, in a world where free broadband could exist, “everything is horribly, brutally possible”. Indeed, that—along with the consequent refusal of the reified object “the economy” or “the markets” as the basis for politics-as-management—was our real disruptive threat. Centrism, then, is disavowal.

And Starmer? As josie sparrow put it, during his leadership campaign:

If Starmer offers hope, it is the hope of the headmaster—kindly, but authoritarian—who says, “well, next time you will behave yourself, won’t you? And then you won’t need to be punished.” The affect is paternal: let the adults take care of this. His promises thus conceal a disciplinary intent: you can have peace, unity, power (of a sort)—but first, you have to put down those silly principles and be sensible.

That disciplinary attitude has had a disorganising effect on the left: we see people giving up on desire (whether through supporting Starmer, or giving up on the hope for change on the national, and even the international level). This could only happen in and through the Labour Party: it could not be imposed by the Tories. Starmidor is enforced disavowal. Centrism then is also pedagogical (like all politics), it teaches us to give up on our desire.

But Starmer is not the only grown-up (and Corbyn, therefore, not the only child). Neither Johnson nor Truss were grown-ups. One could posit this as a merely a question of “vibes” —but ‘vibes’ aren’t trivial, they suggest something more important. ‘Vibes’ are not mere semblance. I’ve argued before that Johnson’s “fuck business” outburst was the key to understanding ‘Johnsonism’. It was also, again, very funny (and had Johnson returned as Prime Minister this week, that would also have been funny). Johnsonism, as I wrote back then, “represents a particular way by which the popular classes can have non-revolutionary effects on the state… [it] is a rather desperate strategy whereby the hegemony of certain, quite surprising, fractions of capital over others… is determined by the ability of these fractions to command the support of electorally decisive fractions of the popular classes.”

Broadly summarised, Johnsonism represented a desperate response by capital, in general, to the threat of Corbynism; and it was the Brexity fractions of capital in the driving seat because their priorities could attract enough popular class votes to win an election, they thereby represented the general interest of capital even if the economic effects of their hegemony were non-ideal. With the threat of Corbyn (or any left electoral challenge) gone, that need to secure broad popular support becomes less important to capital. This means that the internal hegemonic relationships can shift, and that Johnson — seen both as a personal liability (not a fascist, but certainly a bully), and as someone offering certain qualifiedly disruptive policies, particularly around regional spending commitments — can be abandoned.

Within the Tory Party and the power bloc, the effects of the popular classes and popular struggles are indeed “bizarre”. To say that Johnsonism is the effect of popular classes on the power bloc or capitalist state is not to say that this is good, or that it is what the broad popular classes and movements wanted. Between the state and the popular masses there are dislocations, and this is the basis for bizarre effects.

To help us think about this, we need what Althusser described, in his later work, as an aleatory materialism. The word aleatory describes something that is dependent upon chance. Aleatory materialism, then, is a mode of analysis that is attentive to contingency, to swerves and dislocations, to the bizarre —to whatever frustrates the construction and reproduction of the reified objects of political management (including the managerialism of a kind of determinist “Marxism”).4 During the brief premiership of Liz Truss (another non-grown up), we saw perhaps the most aleatory effect of recent politics: the cascading, chaotic encounter between the capitalist state and markets and the popular movement Don’t Pay.

Keir Milburn has argued, persuasively, that “Don’t Pay took down Kwasi Kwarteng” (and I presume he would now extend this reasoning to Truss). As Milburn argues, “while ‘“the markets” were the medium through which the political crisis unfolded, few have recognised the key role played by campaigners in the government’s downfall.” He continues:

recently uncovered documents have revealed that the threat [Don’t Pay] presented was pivotal in forcing the Truss government into an energy price guarantee costing £150 billion over the next two years. That commitment was so big it made the rest of the government’s programme impossible to deliver under current fiscal conditions…by finding the leverage through which to assert the interests of ordinary bill payers, Don’t Pay closed the available space for the Truss government’s programme and put it on a collision course with the bond markets.

All of this is fairly cut-and-dried; but we might want to sound a note of caution in treating this as unambiguously a “win”. To do so seems to deny the aleatory, chaotic aspects of the whole affair. It was a demonstration of popular power, but it was not a demonstration of popular power’s capacity to have its intended effects. Indeed, the immediate political effect was the appointment of the “grown- up” Jeremy Hunt – a kind of British Mario Draghi, formed not by a glittering career as an academic economist, Presidency of the European Central Bank (etc), but by making his fortune through the website “HotCourses” — and the strict limitation of interventions on energy bills. If anybody was calling for these outcomes, they were surely in a very small minority.

The return of the grown-ups within the Tory Party is an attempt to limit the aleatory effects of popular power. It seeks to put an end to the “bizarre period of politics”; to ‘restore’ stability. The pair Johnson-Corbyn is the anti-centrist pair: the pair that offered an election with genuine stakes; the pair of politics constituted to a significant degree by exposure to popular forces.

It is necessary to be clear at this point: this line of argument is not a formalist call for ‘left populism’ of the sorts which hold that “at least” the populist right’s grasp the essentially agonistic nature of politics is something to be imitated. These arguments are wrong, for four broad reasons. Firstly, there is no particular ‘truth’ of politics, let alone any shared truth between right populism and socialist democracy. To speak of any essence of politics is to reify, to construct an object of technical management (in this case, technical management by comms strategists), and to ignore its aleatory and radical indeterminacy. Left populism prefers to emphasise (and reify) a formal similarity over investigating concrete situations. Secondly, socialist democracy is in antagonistic contradiction with the power bloc, right populism is reconfiguration of non-antagonistic contradictions through, the often bizarre effects of popular pressure. Right populism, ultimately, manages popular pressure, albeit not always very well. Thirdly, whilst the general interest of capital (which itself is not a given, but something formed in struggle between fractions) might tend to prefer the centrist suppression of politics, it is not absolutely averse to a polarisation (or pseudo-polarisation) between the centre and the populist right. Finally, we should emphasise that centrism, in its authoritarianism, repression, and racism, is closer to right populism than either are to socialist democracy.

Indeed, to say centrism is the non-fascist suppression of politics is not to say that centrism refuses repression and racism. On Monday, Starmer called for even stricter repression of Just Stop Oil protestors. At least part of this move is to narrow the field of what and who is politically legitimate. Starmer described Just Stop Oil as “arrogant” (transgressing certain limits to one’s own capacity that everyone should modestly accept), and insisted that a Labour government would take action to slow climate change. Centrist politics again reveals itself to be restricted to the rules of the game, an orderly transfer of power. Starmer has claimed Labour’s immigration policy differs little from the Tories (a one-party state, but there are two of them).

For his part, Sunak is extremely unlikely to repeal any of the authoritarian Tory legislation, and is likely to persist with what has been proposed, including restrictions on the right to strike through the imposition of minimum service levels on railways and the underground. Suella Braverman, whose self-proclaimed “dream and obsession” is the sending of deportation flights to Rwanda, returns as Home Secretary, after a long and painful six days reflecting on her breaches of security.

The politics of the Tory cabinet (and their centrist pair, the Labour cabinet), then, are certainly authoritarian, and certainly racist—but they are not fascist. Fascism aestheticises and politicises repression, rather than aiming to make that repression part of the smooth, efficient, non-controversial running of the state. Fascism calls on the People to suppress politics, whereas centrism offers the individualised yet identical voter (a figure constituted entirely through opinion polling) a safe choice. For the centrist, there is no active People, but only a populace that must be protected from inconvenience and annoyance. Indeed, this is what they hold to be the fundamental duty of the state. Centrism differs from both fascism and authoritarian populism its lack of need —and its active refusal — to construct what Stuart Hall (writing about Thatcherism) called “an active popular consent.”

Its racism also differs from that of fascism—and, to a significant but not total extent, that of Thatcherite authoritarian populism. Centrist racism is what Jacques Rancière described as ”Cold Racism”: “primarily a logic of the state and not a popular passion… supported by a substantial part of the intellectual elite.” Of course, it matters little to somebody facing deportation whether the racism of they’re experiencing is ‘ cold’ or ‘hot’5 — but the difference in ‘vibe’ represents a difference in politicisation, and with this an attempt to normalise and obscure the violence of the border regime. If we cannot vote to remove the border regime, but only can vote for Starmer and Reeves to deport more efficiently, the question of the border’s legitimacy is entirely removed from contestation. Rancière’s formulation helps us understand how centrists can claim that they offer the only possible non-racist politics: their conception of what racism is is limited to ‘hot’ racism (ie. racism as an aberration, an uncontrolled popular passion introduced into a stable, rational political order from belo). The cold racism of the state is what they call ‘efficiency’.

Centrism, then, is a sort of democratic formalism, which bears little substantial resemblance to what we, as socialists, might consider democracy, but which nonetheless maintains all the necessary appearances. Centrism as the suppression of politics retains the formal representative institutions — but they are ever more subordinated to the disciplines of “the market”, and the strictures of what is held to be “common sense”. Its ideal form — the paired leaders — allows “choice” within the legitimating transfer of power: certain disagreements between the pair might encourage one to vote for the lesser evil, indeed sometimes a “harm reduction” that may not be the wrong thing to do,, but you are still voting for one half of an inextricable dyad. For centrism, the only legitimate site of politics is the state, and the only legitimate action the citizen can take is voting in an election. Consider the routine disparagement of Labour Party members for daring to choose a leader who was not a centrist; consider how even Tory members could not be trusted to choose the ‘correct’ Prime Minister. Ultimately, to want to engage in politics beyond choosing one of the centrist pair is to render oneself suspect, irrational, childish. What is more, given that centrist politics is constitutively boring, the pair might see themselves as selfless in sparing the people the tedious task of governing, “making tough decisions”, and so on.

The goal is “stability”. But, as Walter Benjamin wrote in 1928, “stable conditions need by no means be pleasant conditions, and even before the [First World War] there were strata for whom stabilised conditions amounted to stabilised wretchedness. To decline is no less stable, no more surprising, than to rise”6 And if one wants more than this stabilised wretchedness? One is an unruly child, who can safely be ignored. The grown-ups are back in charge, you see.

An audio version of this column, read by the author, is available for our subscribers.

-

Ishay Landa. 2010. The Apprentice’s Sorcerer: Liberal Tradition and Fascism. Leiden: Brill. p. 13. ↩

-

Landa. The Apprentice’s Sorcerer. p. 13. ↩

-

Theodor W. Adorno. [1954]. 1992. Notes to Literature, Volume 2. Columbia University Press. p. 316. ↩

-

Louis Althusser. [1982-3]. 2006. “The Underground Current of the Materialism of the Encounter” in Philosophy of the Encounter: Later Writings, 1978-87. London: Verso. ↩

-

Here one might note the absolute irrelevance of the question posed by George Monbiot around Starmer’s support for the public order bill, “does he really believe this sh*t, or is everything he does an attempt to appease the Sun and the Daily Mail, both owned by overseas oligarchs?”, when the cops are suppressing your democratic rights, who cares about Starmer’s subjective motivations. ↩

-

Walter Benjamin. [1928]. 1979. One-Way Street. London: New Left Books. p. 54. ↩