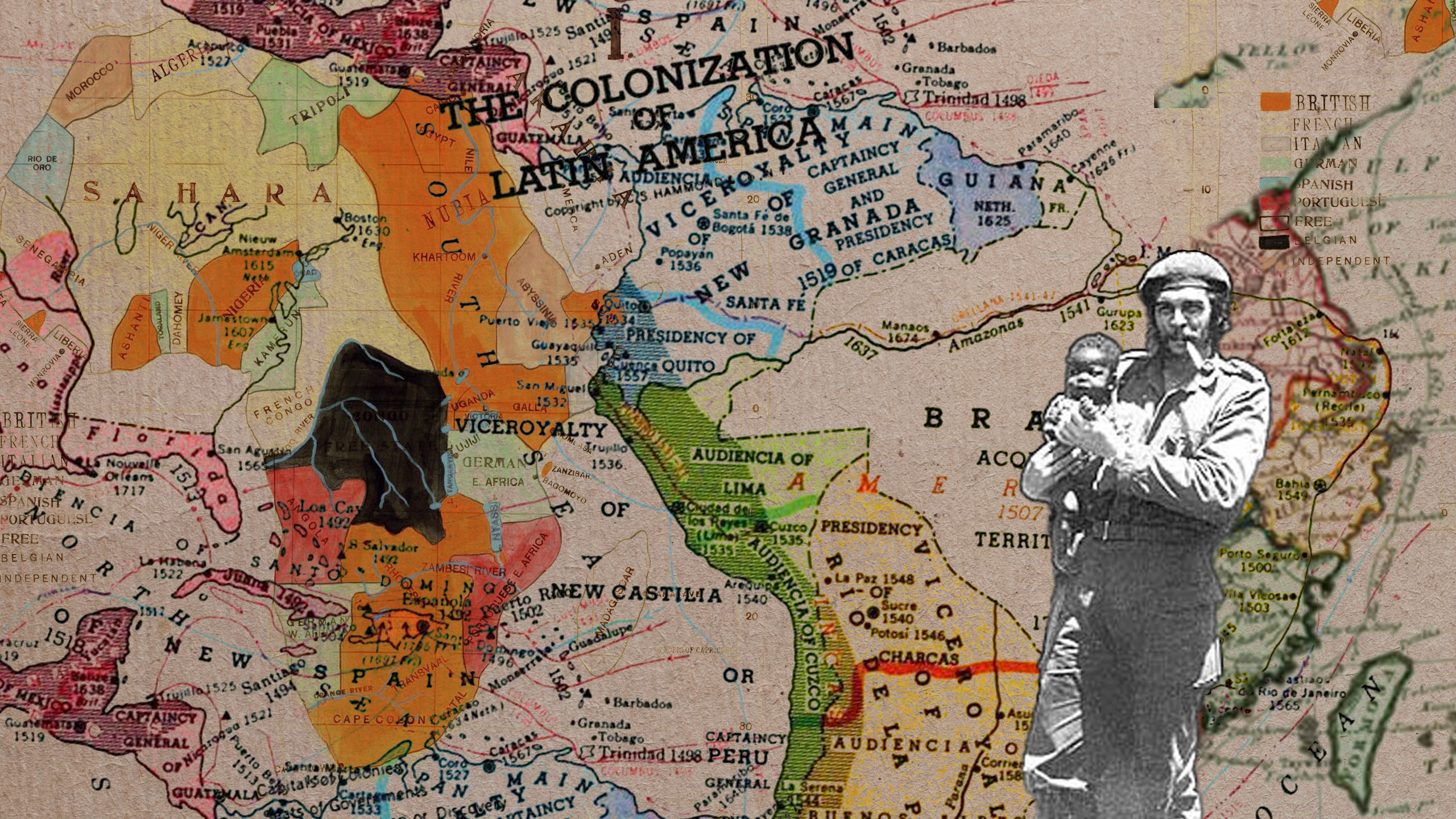

EDITION: 5th Birthday.

On the fifty-fifth anniversary his death, we're reading the young Guevara’s ‘The US Working-Class: Friend or Enemy?

With an upcoming edition Class, New Socialist will explore an often contested topic within socialist circles. Debates are regularly held on the nature of class, what it is to be working-class, whether the ‘Marxist’ conception of class as one’s relation to production still applies, and how class can be understood in the 21st century, with a globalised economy and increasing automation. How can such phenomena be explained by imperialism and locations of production? This article seeks to preview, in a way, one of the themes that may be discussed in the edition, around the role of the working-class in the imperial core and anti-imperialism.

I was born in Argentina; it is not a secret to anybody. I am Cuban and I am also Argentinian […] I feel as patriotic of Latin America, of any country in Latin America, as anybody else and, whenever necessary, I would be willing to give my life for the liberation of any of the countries of Latin America, without asking anything of anybody, without demanding anything, without exploiting anybody.1

Not only did Ernesto ‘Che’ Guevara live by these words, he went even further. A year after giving this speech, he was fighting in Congo, willing to give his life this time for the liberation of an African country. Two years later – fifty-five years ago this month – Guevara was back in Latin America, where he actually gave his life in fighting for the liberation of Bolivia. Reflecting on this unshakeable commitment to acting as he thought, Tirso Saenz, Guevara’s Vice-Minister in the Ministry of Industries, recalls: ‘I personally heard Che several times saying: “I will not die as a bureaucrat. I will die fighting on a mountain.”’2

Guevara’s decision to fight in Congo came from his personal commitment to internationalism and leading by example, his recognition of the strategic battle between capitalism and socialism that was unfolding after the brutal murder of Patrice Lumumba, and his understanding of the transnational nature of imperialism. His numerous leading roles in Cuba’s socialist transition, alongside rigorous self-study and acute intellectual development, were part of a far wider ambition of international liberation.

Years before he set foot on Cuban soil, in fact, a young Guevara had written a text considering the strategies and obstacles for Latin American liberation – and, interestingly, the position of the US working class in this struggle. Written around April 1954, ‘The US Working-Class: Friend or Enemy?’3 is a short and relatively unknown text. The reader should bear in mind that this was written correspondence sent to his family before leaving for Mexico, and it appears never to have been intended for publication. It should not be read as a polished, final article, but a fascinating insight into a young Guevara’s political thought. To mark the fifty-fifth anniversary of Che’s death, I have translated the text, and written this brief consideration of some of its themes.

Guevara wrote extensively on class, imperialism, and Marxism, and by 1967 had developed a profound analysis of Marxist political economy.4 This piece cannot begin to analyse this intellectual development, nor explore the many interventions of Guevara in these debates. Instead, I hope to expose readers to new material from Che, as well as to provoke debate on some of his (perhaps controversial) assertions around the working class, which may still apply today.

‘The US Working Class…’ was written shortly before Guevara – before he became Che – witnessed the fall of Jacobo Árbenz’ revolutionary government in Guatemala in a US-backed coup d’etat. Guevara’s earlier writing (see, for example his famous travel notes, Motorcycle Diaries5) tell the story of a young man who becomes increasingly more aware of the reality of exploitation in his continent, and the human cost of that exploitation. By 1954, the year he turned 26, Guevara’s analysis reflected his increasing certainty that the principal obstacle to liberation of Latin America, and indeed the entire ‘underdeveloped’ world, was US imperialism. This is the context in which he sat down to write ‘The US Working Class…’.

Guevara begins the text by analysing some of the key differences between the countries in which the capitalist mode of production prevailed. He first describes the features of ‘colonial countries’ – nearly all the countries of America, Asia, and Africa – ‘in which the landowning class, allied with foreign capital, monopolises the life of the community and keeps the nation in the state of backwardness necessary for its profits.’There are also, he observes, several countries in which ‘capitalism has not transcended its own borders’, followed by those ‘colonial-imperialist or pre-imperialist’ countries, which, ‘in combination with the paternal capitalists that subjugate it, struggle for immediate markets’ (e.g. Argentina, Brazil, Egypt, India). Then we have the countries ‘whose imperialist expansion stopped after the last war’ (e.g. Netherlands, Italy, France, Britain). But only one nation, in Guevara’s eyes, could occupy the final category of ‘imperialist country in full expansion’: the United States. It was this last nation, this last category, that most interested him:

One wonders why, in the United States, a fully industrialised country with all of the characteristics of capitalist empires, are the contradictions which place capital and labour in conflict not felt?

To answer this question, Guevara analyses the ‘special conditions’ of the US, where he describes how the working class in the US, that is, workers in the imperial core, benefited from economic imperialism and plunder of the underdeveloped world:

Except for black people, segregated and seeds of the first serious rebellion, the other workers (those who have work, naturally) can enjoy enormous salaries compared to those commonly given by capitalist companies, because the difference between what is normally required by the needs of the surplus value and the current pay is more than compensated by groups of workers from two great communities of nations: the Asians and the Latin Americans.

We should note that, for Guevara, segregation tended to exclude black workers from the benefits of imperialism and its integrative effects, although he does not expand on this point in the text.

Drawing a connection between capital flows into the Global South and the corresponding privileges they allow the working class in the imperial core, Guevara asserts that US imperialist expansion was the basis for class compromise with US borders. The victory, in 1949, of the Chinese Revolution removed a major site of imperial extraction, which put this class compromise at risk by potentially forcing imperialist capital to impose reduced standards of living on the working class within the US:

[…] sources of raw material whose labour was extremely cheap are slowly being left out of the radius of action of the imperialist capitalists. But the capitalists are not yet going to suffer the defeat in their own flesh and they transfer it entirely onto the shoulders of the worker. […] Workers in the north also feel the impact in the form of layoffs and lower real wages.

This connection between a revolution in one country – which, for Guevara, axiomatically involved said country’s control of its own labour and natural resources – and the drop in living standards for the working class in the imperial core is a crucial one. Over a decade later, after his experiences at the heart of Cuba’s socialist transition, Guevara would call for “two, three, many Vietnams,” “throughout the world” exploited by US imperialism. But here, at the age of 25, before any of that, we find him already acknowledging that any anti-imperialist liberation struggle must necessarily be international, and rightly predicting that, with the Chinese markets closing, the US would turn even more violently to America and Africa.

Furthermore, Guevara correctly argues that, in the face of emerging revolutions that threatened both US hegemony and the living standards of the US working class, the US had two choices: total war against the socialist world, or abandoning Asia in order to focus completely on America and Africa, ‘sustaining, of course, small limited wars that allow it to maintain its arms industry without loss of life, as there will always be treacherous rulers ready to sacrifice their lands for the crusts thrown by the master.’ Unlike America, where the US has ‘total dominion’, he predicts – again, accurately – that Africa, where the US had only ‘small territorial patches’, would become the next site of US imperialist expansion.

As the self-appointed leader of the ‘free world’, the US must have a pretext for interference in the underdeveloped world – a pretext it finds in the threat of ‘international communism’. But this threat, Guevara insists, is useful not only for US international interests, but for maintaining class compromise and ensuring the support of the US working class for the imperialist state. Guaranteeing working class support for its imperialist expansion was of critical importance to the US ‘since the sudden loss of cheap sources of raw materials would immediately provoke the immanent conflict of the contradiction between capital and labour, and the result would be disastrous for it.’

In this context, with the working class’s standard of living dependent on imperialism, US labour unions have little motivation to challenge the general order of things, and instead serve ‘to file down the revolutionary power of the masses’. Guevara concludes that, in the fight for liberation and against the imperialist expansion of the US, the US working class will make the ‘logical’ choice to act in unison with their government as it struggles, under the banner of anti-communism, for economic control of Latin America. Guevara writes that he cannot and does not expect US workers – far away, and subject to capitalist-owned media – to be convinced that each renewed defeat of imperialism (i.e. each time an underdeveloped country asserts control of their own markets) removes yet another prop that slows ‘the process of the internal decomposition of capitalism’

In the Communist Manifesto, Marx and Engels predicted that communism would first emerge in the most developed capitalist countries. Marx later reconsidered this position to some extent, but it nonetheless made its way into certain ‘common sense’ Marxisms of the 20th century. It was, in reality, in (some of) those countries characterised by ‘backwardness’, imperialist exploitation, and non-industrialisation, where struggles against the capitalist mode of production were most pronounced. Guevara recognised this, and understood that every national revolution would be a body blow in the battle against imperialism. He also knew that each revolution would help to provoke further the deep conflict between capital and labour in the imperial core:

Let us prepare, then, to fight against the entire people of the United States, for the fruit of victory will be not only economic liberation and social equality, but also the acquisition of a new and welcome younger brother: the proletariat of that country.

This little-known text is important as a historical piece, documenting the young Guevara’s analysis of the material conditions of Latin America, the strategies of defeating US imperialist expansion, and the ways in which the superpower maintains control of markets and raw materials of the underdeveloped world.

It also tells us something about Guevara’s internationalism: that it was forged in his youth, through travelling in Latin America, witnessing extreme poverty and exploitation, and experiencing first-hand the overthrow of a democratically elected leader. His internationalism was also incredibly practical. It derived from his evolving analysis of imperialism and underdevelopment. He was convinced that to liberate his continent - indeed, to liberate all of the underdeveloped world - imperialism would have to be defeated; and that this defeat, just like the flow of capital, would necessarily be international.

It tells us, too, that Guevara, at this time, considered the US working class to be complicit in the subjugation of the underdeveloped world – that, at the very least, it was forced to be complicit, in large part because their living standards depended upon their government’s imperialist expansion.

The questions raised by this text around imperialism, and how it relates to the working class in the imperial core, are perhaps not adequately explored in our socialist movements. Anti-imperialism at home should unequivocally begin with the understanding that the working-class has benefited, and continues to benefit, from imperialism abroad.

Nearly seven decades after Guevara wrote this text, it would be fair for anti-imperialist movements in the Global South to ask: The Working Class in the Imperial Core: Friend or Enemy?

All translations are my own.

All quotations unless specified are from the article ‘The US Working Class: Friend or Enemy?’.

-

Guevara, Ernesto. Contrarréplica del Che en el XIX periodo de sesiones de la Asamblea General de Naciones Unidas. 1964. Archivo Centro de Estudios Che Guevara. 2021. ↩

-

Saenz, Tirso, quoted in Yaffe, Helen. Che Guevara: The Economics of Revolution. 2009. P.257. ↩

-

Guevara, Ernesto. “La Clase Obrera de los Estados Unidos… Amiga o Enemiga?” in Reloba, Xenia & Martínez Heredia, Fernando. Materiales de la revista Casa de la Américas de/sobre Ernesto Che Guevara. La Habana. Fondo Editorial Casa de las Américas. 2017. pp. 65-68. ↩

-

For the best analysis in English of Guevara’s intellectual development, see Yaffe, Helen. Che Guevara: The Economics of Revolution. 2009; particularly chapter 9: Critique of the Soviet Manual of Political Economy. ↩

-

Guevara, Ernesto. Motorcycle Diaries. Ocean Press, 2003. ↩