EDITION: CLASS.

Understanding monetary policy requires grasping the peculiar transnational class position of some of capital's key organic intellectuals: central bankers.

When markets took against Liz Truss’s ‘fiscal event’ in the autumn of 2022, both her Chancellor, Kwasi Kwarteng, and the Governor of the Bank of England, Andrew Bailey, were at the IMF’s annual conference in Washington, DC. Kwarteng pulled out of the event early as yields on government bonds shot upwards into crisis territory. The Truss government had announced large tax cuts in an already inflationary environment. The great and good of enlightened global capitalism – from IMF chief Kristalina Georgieva to US Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen – made their displeasure with the Truss ‘mini-budget’ clear. In response to the financial market turmoil, Bailey had already announced the Bank would temporarily start buying government bonds, with the idea that this would raise their price and force down yields. Those same yields were undermining the pension system, which was ailing due to an apparently innocuous hedge against low returns on their holdings of government bonds. The problem was that now, yields on government debt had spiked and the pension funds were being forced to sell off assets – particularly government bonds – in order to meet margin calls by the asset managers who oversee these normally mundane hedges. The Bank had no choice but to bring down government bond yields in order to save the pension system. But, unlike previous rounds of bond buying to support the economy as a whole, this one came with a strict two-week lifespan. The Bank’s decision to end its bond buying scheme led to accusations that they had created a cliff edge which effectively forced Truss out of office.

We can only speculate as to whether the bond buying programme was expressly designed to force Truss into a climbdown. Bailey has argued that the Bank had to put an expiration date on the scheme in order to save its own credibility. Few would believe in the Bank’s ability to impose discipline on the markets in future if it continued to lower bond yields indefinitely. Following the Truss debacle, the Bank’s interest rate rises only accelerated. Amid a widespread crusade to restore the Britain’s – and the Bank’s – credibility, Kwarteng’s orthodox replacement Jeremy Hunt argued there was ‘no alternative’ to further interest rate rises. The Bank made restoring slack to the Britain’s ‘very tight’ labour market – essentially, increasing unemployment – central to this crusade. Economists like Isabella Weber and unions like Unite made it clear that attempts by some companies to maintain their profit margins in response to supply shocks had driven inflation, not workers’ wage rises. However, officials at the Bank claimed that the only way to restore ‘stability’ was to prevents workers from pursuing ‘unsustainable’ further wage rises. At the same time, rising interest rates contributed to the housing crisis by forcing up rents and mortgages. It is clear, then, that inflation is a distributional struggle, which central bankers – themselves bearers of particular transnational class relations – must attempt to manage. In seeking to resolve that struggle and restore its ‘credibility’, the Bank has resorted to a form of controlled detonation.

Following the financial crisis of 2007-8, central bankers like former Bank Governor Mark Carney called on his fellow elites to help build a more ‘inclusive capitalism’. This would imbue major decisions makers – financial investors, professional and academic economists, advisers and strategists, regulators and politicians – with a ‘sense of the systemic’ consequences of their actions. This was an attempt by a group of transnational intellectuals to re-build the ‘social capital’ of ailing ‘market economies’. They set their sights not only on making elites more ethical, but on restoring the faith of the mass public in capitalism and its leading institutions. These central bankers and their fellow intellectuals wanted to restore social stability. Now, they are imposing socially destructive interest rate rises – perhaps even in excess of what their mandates require – in order to curtail what they view as destabilising distributional conflicts. These rate rises may bring about a form of stability, but it will be -as the old financiers’ saying goes – the stability of the graveyard. Inclusive capitalism – including public investment, efforts to tackle climate change and a more functional international monetary order – will all just have to wait until inflation returns to target.

Today, politics is increasingly divided between two camps. ‘Stabilisers’ like central bankers want to pattern social behaviour in ways that encourage certain kinds of rationality and order. Self-styled ‘disrupters’ like Truss and the Brexiters want to ‘dis-embed’ markets and let the ‘natural’ justice of competition do its work. The left has been marginalised – often, no doubt, deliberately – in the midst of this discussion. Yet the stabilisers are poor defenders of stability. Their politics is rooted in a peculiar transnational class position. That class position has developed within a loosely integrated architecture of global governance. These are Gramsci’s ‘organic intellectuals’ of global capitalism.1 Neither the principal owners of capital, nor fitting neatly into the middle or working classes, these organic intellectuals are responsible for rule-setting and norm-making across institutions. They are supposed to make the anarchic short termism of capital somehow ‘coherent’. Sometimes, they work within the state. At others, they work in regulatory institutions. At others still, they take that expertise into the private sector. At all times, they are a product of capital’s need for intellectual work that can help it navigate a complex and high-risk environment. Take former Bank Governor Mark Carney. Educated at Harvard and Oxford, Carney was a Goldman Sachs economist for over a decade. Migrating into the public sector in the 2000s, he became Governor at the Bank of Canada in 2008. George Osborne lured the ‘superstar’ central banker to Britain in 2013 to become Bank of England Governor (2013-2020). At the same time, he chaired the Financial Stability Board (FSB) (2011-2018), which was set up by the G7 to monitor the global financial system in the wake of the 2007-8 crash. After stepping down from the Bank, he became UN Special Envoy on Climate Change and Finance and a Vice-Chair at Brookfield Asset Management. Or take the membership of the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee (which meets to set official interest rates). Across the CVs for all members (available at the Bank’s website), major multinationals, financial firms and business associations feature prominently (Goldman Sachs, the Confederation of British Industry (CBI), BP, Shell, NatWest, J.P.Morgan, Credit Suisse, and so on). In most cases, MPC members have predominantly been employed as chief or senior economist. International official institutions (the IMF, the World Bank) also feature prominently alongside experience at either the Bank or the Treasury. This is in numeric terms a small group, which nonetheless wields very large influence through the ways in which it organises ideas about how society should work and implements rules and standards for governing capitalist economies.

While this transnational intellectual strata has emerged as an increasingly autonomous political actor in recent years, its pursuit of an inclusive capitalism has remained subordinated to the right’s belief in the virtues of ‘sound money’ and the benefits that should fall due to ‘prudent savers’. From 2016 on, the Tory government, its backbenchers and the right-wing press began to harangue the Bank for the negative effects of loose monetary policy on savers. Those who had prudently set aside cash in the good times now stood to lose out as interest rates were cut to zero. Moreover, the Bank was seen as an ‘elitist’, unelected and technocratic institution. Carney was pilloried by the Daily Mail for his ‘jet-setting’ lifestyle, links to Goldman Sachs and apparent Remain sympathies. An alarming opposition between the ‘common sense’ right which supported ‘real’ people and meddling technocrats was created. Debtors were being coddled while savers – usually older voters who had paid off their housing debts – were being ignored by loose monetary policy. In Theresa May’s words, ‘those with mortgages have found their debts cheaper… those with savings have found themselves poorer.’ This has applied pressure on central banks to raise interest rates further and faster once inflation began to rise due to supply shocks in 2021. As has been widely noted, this had little to do with excessive money creation by the Bank and more to do with easily disrupted global supply chains. The left, then, needs to formulate a positive alternative narrative about monetary policy that can act as a counterweight.

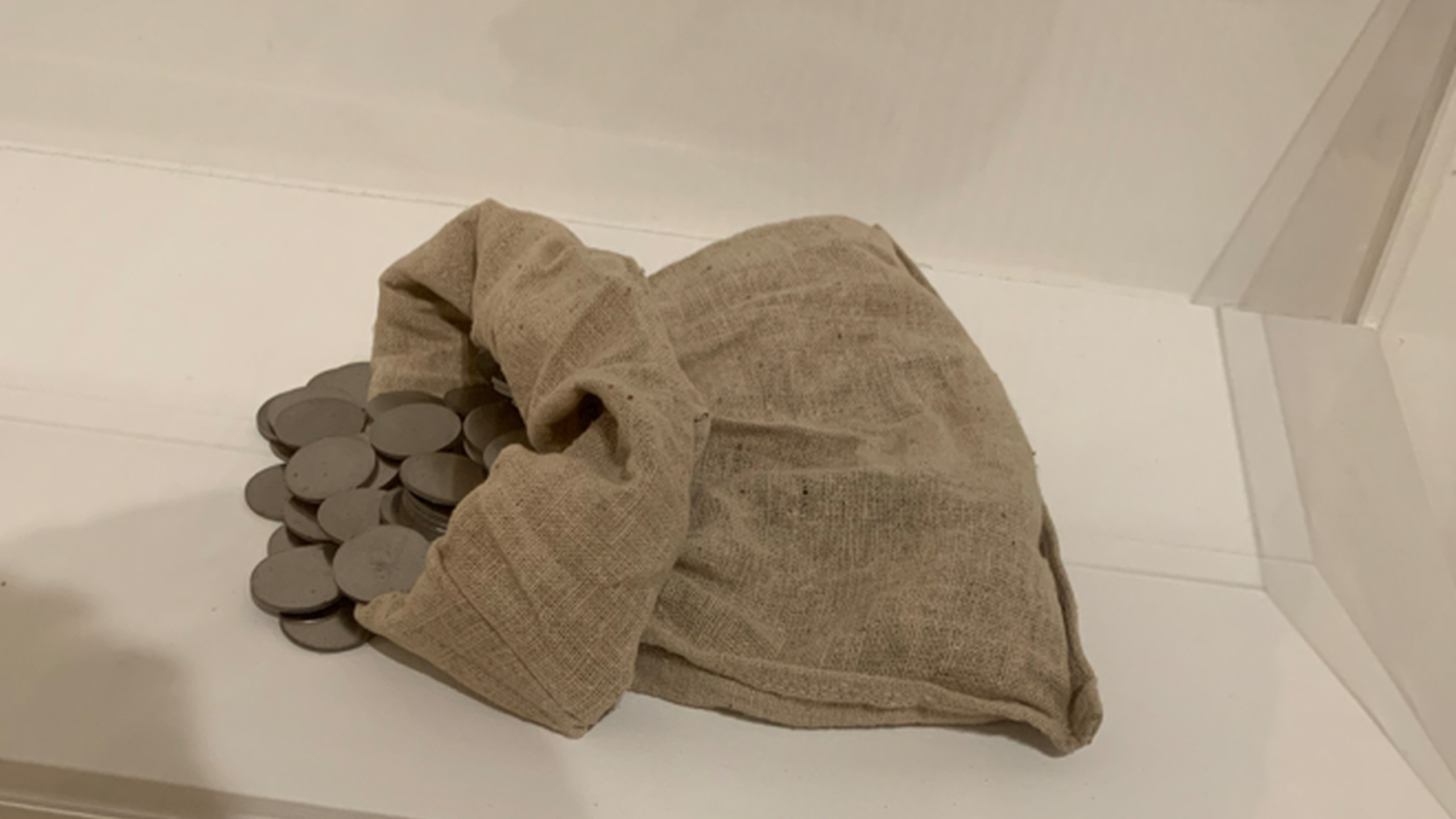

Photo credit: The Author

‘A Rat Became the Unit of Currency’

In Zbigniew Herbert’s 1982 poem Report from the Besieged City, the narrator acts as ‘chronicler’ – ‘I don’t know for whom’ – of events in the dying days of a long and hostile siege. Under the pressure of external assault, the city has seemingly collapsed into a state of exhausted absurdity. As the store houses empty, a rat is declared the unit of currency. The poet shoulders the heavy burden of seeing through the chaos to record only the facts of the situation:

I avoid any commentary I keep a tight hold on my emotions I write about the facts only they it seems are appreciated in foreign markets

This could be the motto of an independent central banker in the age of the breakdown of neoliberal order. The Bank of England has in recent years come to occupy this position of chronicler of the dysfunctions and absurdities of a monetary order that it perceives as similarly under siege. Its publications amount to an epic chronicle of interconnected risks – climate change, Covid-19, Brexit, deglobalisation and market fragmentation, productivity and wage stagnation, emerging market financial fragility – delivered in dispassionate technical prose. Herbert’s narrator wonders whether his words will be heard by ‘our/friends beyond the sea’, but concludes ‘those struck by misfortune are always alone.’ We can only imagine how Andrew Bailey felt among the elite in Washington as he reaffirmed his commitment to cutting the government’s lifeline, but he at least did seem to have allies overseas.

Herbert’s line about a rat becoming the unit of currency also forms the epigraph of Don Delillo’s 2003 novel Cosmopolis. In the novel, the quote is used as a slogan by a riotous group of terrorists, whose only motivations appear to be to cause chaos and murder members of the global elite. At the time they attack the billionaire protagonist’s armoured car, they have already murdered the head of the IMF. The slogan – ‘A rat became the unit of currency’ – is graffitied on the sides of Wall Street buildings. Unsurprisingly, their actions tank the dollar and cause almost inestimable losses for the world’s rich. We are not quite in that world yet. But there is a peculiar analogy. Extinction Rebellion have targeted the Bank of England in recent years, gathering at its doors and hurling red paint at its walls. In the view of this rather more sedate crowd, the Bank of England was responsible for continued financing of global polluters. On the other side of the Bank of England’s massive walls and its layers of metal detectors and security gates, there is a strange calm. From the hushed atrium you can see into the central courtyard, where Governor Bailey is known to take calls in the summer months. The Bank makes its own honey from the bees that nest in the trees there.

Like the impassive billionaire in his armoured limousine in Delillo’s novel, the Bank seems to survey the chaos as if through a layer of virtually impenetrable armour. What these officials see outside is an increasingly destructive and turbulent world. Carney, for example, was fond of the following form of words: ‘Of course, markets only clear in textbooks. In reality, people are irrational, economies are imperfect, nature itself is unknowable.’ The same, or close to it, appears in speeches of 2015, 2018 and 2019, each one delivered to relatively ‘elite’ economic or financial audiences (the ‘Harvard Club of the UK’, the Economic Club of New York, and the ECB). Economists have long known that markets can be ‘irrationally exuberant’. But there is an interesting slippage in Carney’s telling: not only markets, but people are irrational. Looking out at the world from behind their reinforced windscreens, the people of Davos – private sector economists and CEOs, asset managers and their strategists, global regulators and their supervisory staff – might perhaps see this ‘irrational’ and ‘populist’ public as a risk in itself. Freed from the strictures of office, Carney, in his 2021 departure-lounge-manifesto Value(s): Building a Better World for All, discusses at length how crises of democracy, climate and health are the product of the irrational tendency to let the market dominate all aspects of social life. What he defines as participatory and transformational global leadership – building popular consent while mobilising private finance for the public good – can help to prevent these various crises from consuming the social order. What Carney wants to avoid is a world where a rat has become the unit of currency – that is, where what is valuable about the institutions of ‘market society’ is dissolved and chaos takes over from order.

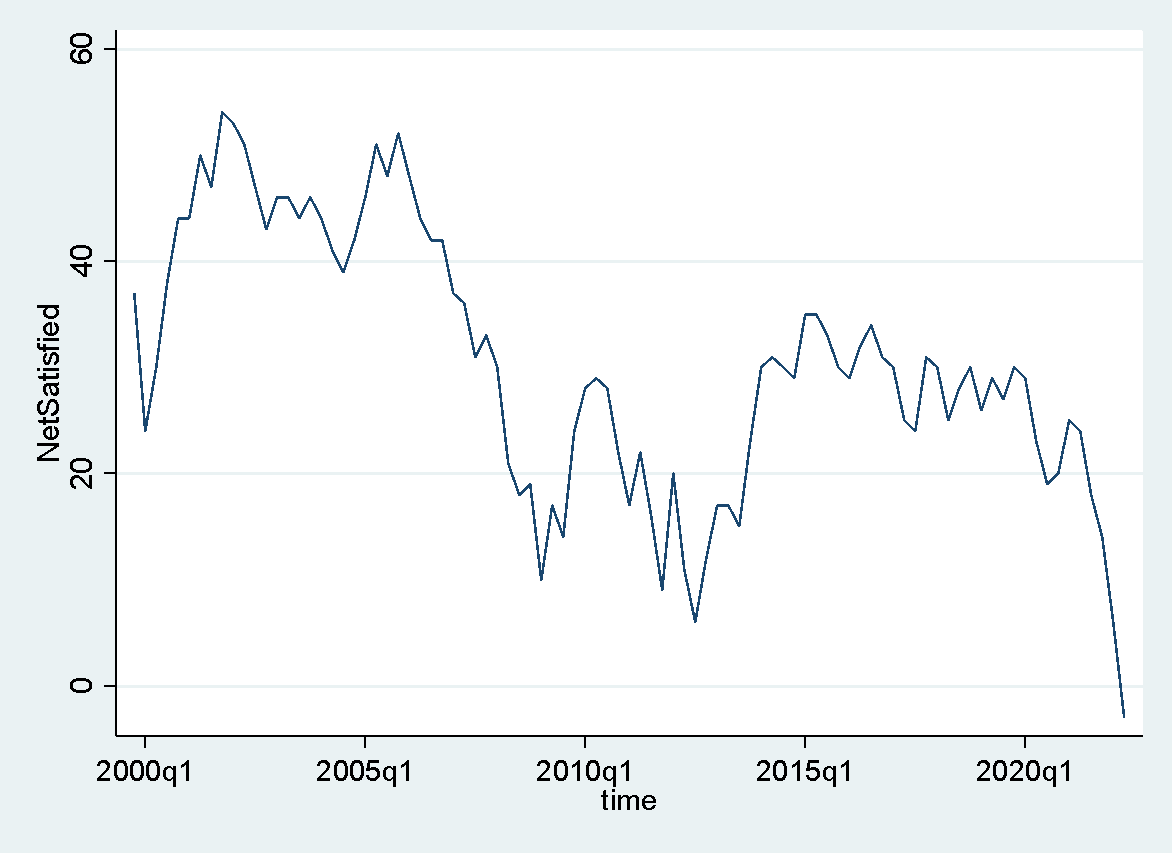

There is a clear awareness among central bankers and other regulators and technocrats that capitalism today is suffering from popular legitimacy problems. The Bank is well aware of the loss of its own public standing, and of the leading institutions of contemporary capitalism more broadly, since the crash of 2007-08. Former Bank Chief Economist Andrew Haldane addressed the Occupy Movement in the wake of the global financial crisis. He claimed that the protestors were right to point out that rising inequality had gone hand-in-hand with rising levels of household debt. Haldane went on to launch communicative initiatives designed to stem this system-wide loss of legitimacy (what he called the ‘twin deficits’ of falling public trust in and understanding of the institutions of the market economy). The Bank now runs educational initiatives to increase public understanding of the economy, essentially attempting to re-format the public as good consumers and investors. Yet, despite Haldane’s efforts and his recent protestations, when inflation returned in 2021, central banks and the world’s enlightened regulatory elite imposed unprecedented, globally coordinated rate rises on their respective publics. As Adam Tooze lamented in the pages of the Financial Times, ‘How long is it since we were calling for a new social contract [and] supporting democracy against lopsided capitalism?’ Central banks are of course mandated to pursue low inflation. But rate rises take twelve to eighteen months to bleed through to the economy. Raising interest rates by five percentage points from rock-bottom lows in the space of less than a year suggests that concerns about inclusion and stability have been shunted aside. Conservative forces have long been mobilising pressure on the Bank – via the press and Treasury Committee hearings – to stop ‘printing money’ and reward ‘prudent savers’ with higher interest rates. A long-held suspicion that the Bank was propping up the government by purchasing public debt on secondary markets also fed the belief that there was an establishment stitch-up going on: regulators and technocrats around the world were colluding against the free market. These political arguments point to the sharp divides that exist between different social groups over the appropriate forms and functions of money.

Detail. Photo credit: The Author.

Money, Interrupted

In 1996, the artist Cornelia Parker paid a visit to the Royal Mint in Pontyclun, Wales, where she managed to persuade the authorities to give her some unfinished coins. The ‘metal disks’ were, she says, retrieved from the process ‘just before they were struck.’ The result is a ‘faceless’ blank, collected and positioned by Parker in a parody of the real thing. In the exhibition piece, Embryo Money (1996), the embryonic coins spill from a hessian moneybag, like a detail from a carefully posed Elizabethan portrait: still-life and still-born. In viewing the piece, we are asked to reflect on the way in which these faceless artefacts assume the social power of money only once they are minted. As Parker notes, the half-coins become ‘a currency interrupted before it had value, before it had accrued power.’ Money today does not consist principally of coins, but is rather a hierarchy of promises to pay with central bank money at its apex. Far from minting or printing money, the Bank of England’s role is to convert financial sector assets into central bank liabilities (Walter Bagehot’s dictum that these should be good assets and that the Bank should impose a high discount has proved optional). But Parker’s metaphor can be extended: an interruption in the ability to smoothly convert one financial claim into another – and ultimately into a final form of settlement – potentially risks the money-ness of the entire sector. Financial claims are reduced to the status of Parker’s blanks when they cannot be converted into other claims further up the hierarchy of finance. Working in the tradition of Bagehot, the economist Perry Mehrling argues that in modern market-based financial systems, financial institutions (banks and non-banks) finance long-term (capital market) lending with short-term (money market) borrowing. Because of this maturity mismatch, they may need to raise cash by selling or borrowing against assets in order to meet present payment obligations. This is how they meet payments on their liabilities (short term borrowing), which finance their assets (long-term lending). But if everyone sells the same kind of asset at once in search of cash, they may not find a buyer. Once the financial sector’s own dealer systems have broken down, the central bank must step in. In Marxist terms, this function of the central bank can be thought of as maintaining the viability of monetary exchange in a system of decentralised production and consumption.

However, this role as guarantor of the ability to pay sits uncomfortably alongside, and sometimes comes into conflict with, more recent conceptions of the role of central banks. Such discretion over the power to produce money-ness in the wider financial system jars with central bankers’ conception of themselves as a technical, equilibrating force in modern economies. Over the course of the 1980s and 1990s, central banks’ power to set interest rates on short-term borrowing was established as the primary tool of macroeconomic demand stabilisation. In a policy regime that the economist Benjamin Braun calls central bank planning, carefully calibrated signals were sent to markets in order to target inflation in the medium term: a little loosening here would stimulate economic activity; a little tightening there would slow the economy down. The econometric models that became widely used at central banks in the 1990s (the famous three equation New Keynesian model) assumed that economic actors operated according to shared laws of rationality, while money figured only in the form of ‘nominal rigidities’ or ‘sticky prices’ (that is, lagged adjustment of prices to changing supply and demand conditions). These rigidities were what gave monetary policy its short-term effect: by loosening interest rates now, real economic activity would rise towards its long-run potential. Above that long-run potential, further increases in activity would become inflationary. But if all went perfectly, market actors would anticipate a forthcoming rate rise and activity would slow down. Thus, volatility of interest rate changes, output growth, and inflation would all be reduced. Central banks were modelled as making short-run trade-offs between output and inflation (so-called Taylor style rules). Because central bankers were by nature conservative and reputation (rather than election) obsessed, they – not elected politicians – could be trusted to manage the ‘political business cycle’. Very high interest rates would only be necessary when policymakers forgot that monetary policy was ‘neutral’ in the long run – i.e. they kept rates too low for too long and allowed social inflation expectations to rise. Indeed, Carney defended the Bank from accusations that it was meddling in politics by reminding people that ‘long-run monetary neutrality’ meant that by definition the central bank could not affect the ‘real’ productive capacity of the economy. This was a subtle way of suggesting that the major decisions about the underlying structure of the economy were up to politicians, not the Bank. However, this invocation of monetary neutrality – which meant that in the long run, monetary policy only produced inflation – reinforced the conservative pressure that the Bank was simply ‘printing money’.

The dilemma for central bankers today is that, as they raise interest rates after a long period of record lows, vast quantities of assets currently held by the financial sector (for example, government bonds issued with low, fixed returns) are being heavily devalued. As the yields on these assets rise (and their prices fall), the balance sheets of the institutions that hold these assets look increasingly risky. Throughout the 2010s, the view of the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) – the important hub of monetary research which is co-owned by central banks – was that, by lowering interest rates, central banks were stimulating financial risk appetites as a means to increase ‘real’ economic activity. As it turned out, it was not low interest rates that led to financial instability, but the effect of raising them in the face of high inflation. This partly explains the run on Silicon Valley Bank in March as well as the pension fund crisis of last autumn. The dilemma becomes acute when central banks launch ad hoc bond buying operations to stabilise certain sectors, while raising interest rates which curb demand and potentially raise unemployment. This can politicise the statements of central bankers, as Andrew Bailey found when he suggested that workers should not seek large pay rises in 2022. Tight monetary policy is profoundly socially and economically destructive, not only for renters and workers, but for many asset owners and financiers. There is a long-standing conservative economic belief, however, that such treatment is necessary to purge the economy of excess. This monetary moralism dovetails with the widespread belief that ‘prudent savers’ lost out in the era of low interest rates and should now get their belated returns. The view that central banks kept interest rates too low for too long in the wake of the Covid-19 crisis risks becoming a dangerous orthodoxy. In the wake of powerful social conservative pressures for a restoration of ‘sound money’, central banks’ vision of ‘inclusive capitalism’ has been swept aside.

At a recent retrospective, Cornelia Parker’s blank coins were exhibited alongside her most famous piece, Cold Dark Matter: An Exploded View (1991). The piece consists of the remains of a shed, which – with the assistance of the British army – Parker had subjected to a controlled detonation. The fragments of the shed are hung in suspended animation in a re-creation of their form milliseconds after the detonation. While the interrupted process of monetary production withdraws the coins from the politics of time, this piece seems to suspend the destructive effect of time itself. If interest rates are in part an expression of the politics of time, rapid increases in the policy rate amount to both an acceleration of these combustible politics and their sudden arrest – an interruption of rising social conflict through a controlled detonation. Quite how controlled this detonation is – what unintended consequences and perverse dislocations arise from it – remains to be seen. Writing about the present is a bit like walking into the room where Parker’s piece is displayed. Although we can clearly see the explosion’s path outwards, we do not quite know where the pieces will fall. Rather than pursue their vision of ‘inclusive capitalism’ in difficult times, central banks have opted to restore order through the controlled detonation of interest rate rises. Loose monetary policy was used to maintain asset prices and access to cheap credit, driving up the accumulation of debt vulnerabilities in the process. Tight monetary policy is now being used to re-impose discipline on social groups attempting to maintain their income levels and avoid debt default. The politics of monetary order today show that central banks are a potentially explosive and disruptive political force in their own right. Whether things could have been different is hard to say. There is widespread conservative political and social pressure for curbing inflation and restoring returns on savings, which might circumscribe any central bankers’ room for manoeuvre. How things will land is yet to be decided.

Mission-Oriented Central Banking?

Despite the left’s exclusion from the political debate in Britain, it is worth thinking about how central bank policy might be approached by the left in future. There is little chance of a challenge to economic orthodoxy arising within official British politics today, but there are other places in the world and there will be other times when the left is closer to power. One powerful reform might be to re-order central banks’ mandates such that their responsibility to target inflation is secondary to coordination with the government around the re-development and reform of the economy. One way to provide democratic legitimacy for such an arrangement would be for these goals to be reviewed at the beginning of each parliament and in consultation with trade unions and other social groups. Of course, this would greatly increase the politicisation of monetary policy making. It would potentially accentuate the ‘political business cycle,’ the destabilising effects of which inspired the early advocates of central bank independence. But it would make the development goals of society clear in a way that has hardly been detrimental to, say, climate policy in the era of net zero targets and annual COP meetings. A clearly stated plan of this kind would help leftist governments go against the grain of neoliberal policy, while – given the political economy constraints on the unfettered exercise of state discretion – not jettisoning entirely the credibility provided by an independent inflation targetter.

Under these arrangements, the central bank would still be required to keep inflation low and stable, but would need to consider the government’s aims more overtly in doing so. In Britain’s case, the terms of the Bank’s existing mandate would be inverted: the Bank would need to consider how to keep inflation low ‘subject to’ the needs of the government’s strategic plan for the re-development of society and economy. Given the popularity of ‘mission-oriented’ state intervention today, such a plan could even be styled as a new form of ‘mission-oriented central banking’ in which all the tools in the Bank’s arsenal – its lending and asset purchase programmes as well as its powers over financial regulation – could be mobilised to help steer the economy in a more socially just direction.

Of course, in advocating such monetary reforms, there is a risk of embracing the fantasy that the material conditions of life can be transformed by legal diktat. Critiques of proposals for monetary reform that do not tackle the social relations of production have a long history, dating back to Marx’s critiques of Proudhon. Yet just as Marxists recognise that the state is a terrain of struggle and not simply an ‘instrument’ of the ruling classes, the power to determine how monetary exchange is reproduced needs to be recognised as a site of contestation. As Stefan Eich has shown in his book The Currency of Politics, the core contribution of Marx towards a theory of money was to show how money cannot simply be reformed by state dictat because it is fundamentally a creature of capitalist exchange relations. Isabella Weber similarly argues that money for Marx is fundamentally (if not exclusively) the form in which social value is realised in capitalism and thus plays an essential role in capital accumulation. This gestures towards a point of crucial political importance: the state’s power over money-ness is not complete (since money is the product of capitalist exchange relations not the state), but is certainly decisive in a crisis when a lender or market maker of last resort – that is, the central bank – is necessary to keep payments flowing.

Central bankers themselves are — as I argued above — increasingly politically active. Their transnational intellectualism has led them to propose forms of ‘inclusive capitalism’ that would make elites more ‘ethical’, but also equip the public at large with a greater sense of economic ‘rationality’. As we have seen, however, these efforts have proved inadequate tools to contest the push – on the right, but also within the institutions of global governance – for a return to ‘sound money’ and rapid interest rate rises. This raises an important question about the extent to which such ‘organic intellectuals’ and the tools they have built for their own purposes could ever be relied upon to deliver on a proposal of the kind suggested above. The question of whether the Bank would have been forced to intervene in sovereign debt markets in defence of a Corbyn government – and for how long it would have chosen to do so – will remain hypothetical. No left-wing government in the world has yet managed to engineer a break with the macroeconomic arrangements of the 1990s, when central banks were overwhelmingly made independent. A new generation of leftist leaders in Latin America is now grappling with that global legacy. How leftist governments tackle central bank independence – and their close relationships with the leading institutions of global capitalism – will no doubt be significant in determining their fate. Could Carney’s ‘sense of the systemic’ have worked as an alternative to ‘sound money’ orthodoxy? It is unlikely. When defending the Bank’s loose monetary policy, Carney argued that monetary policy was ‘neutral’ in the long run. This implied that rates would need to move higher as inflation returned, but at the same time implied that low interest rates would ultimately cause inflation to return. Central banks have ended up in a trap partly of their own making: they are now widely held to be partly to blame for the current high levels of inflation, which some see as a product of the stimulus that followed the Covid-19 pandemic rather than a product of supply chain disruptions. Technocratic defence seems to count for little in the face of an orthodox onslaught that favours unemployment and recession in order to tame inflation. As argued above, we should not mistake a preference for systematisation, rationality and stability for something more democratic and socially just than it really is. The stability of inclusive capitalism rapidly became the stability of controlled detonation.

Rather than wonder what central bankers could have done differently in recent years, it might be more productive to think about what the left should say it wants from monetary policy. The Corbyn leadership of the Labour Party often avoided the issue of the monetary policy framework. It appears the Party opted to supplement the Bank’s existing mandate with additional subclauses (similar to the green mandate eventually adopted under the Tories). However, the continued primacy of price stability means that when inflation rises the Bank’s central priority continues to be to tighten markets (at the same time as raising government borrowing costs), which undermines whatever other, secondary mandates it has adopted. Displacing the primacy of price stability might facilitate the coordination between different state institutions that is necessary to fund the green transition. A ‘green industrial revolution’ of the type once proposed by the Corbyn opposition would require a facilitative interest rate environment that was capable of ‘looking through’ conjunctural bursts of monetary and financial market instability. This is at the heart of the idea of ‘mission-oriented’ central banking. Such a rearrangement would potentially institutionalise a left alternative to the prevailing right-wing pressure for ‘sound money’. Skirmishes today between leftist governments and their independent central banks lead to little in the way of meaningful reform. A combination of legal changes, clearly articulated political priorities and mass public pressure could help to force central banks to support governments in these missions. The left should, then, build an effective counterweight to both the conservative politics of ‘sound money’ and the inadequacies of technocratic ‘inclusive capitalism’ that is currently wreaking havoc for so many around the world.

-

Antonio Gramsci. [1929-35]. 1971. Selections from the Prison Notebooks. London: Lawrence and Wishart. pp. 6, 16. ↩