EDITION: CLASS.

Coercion and control are the tactics of abusers, and coercing and controlling the working class is the job of the police. Abolition is class struggle!

Thinking about the origins of policing and prison systems often conjures up images of rampant crime sprees and untameable social disorder on the streets of Victorian England. These fit within a story that conceptualises the police as primarily a response to the harm experienced by ordinary people in society. Even within abolitionist circles, there is sometimes tacit acceptance of the idea that the police came out of the state’s proposed solution – albeit a failed one – to harm and violence. We push back against this narrative, as the idea of policing institutions as a response to harm and violence between ordinary people is a powerful ideological fiction. Policing, in the first instance, is a response to the organised, collective power of the working class. It is only thereafter naturalised as a response to individualised harm, as part of legitimising the existence and function of police in society.

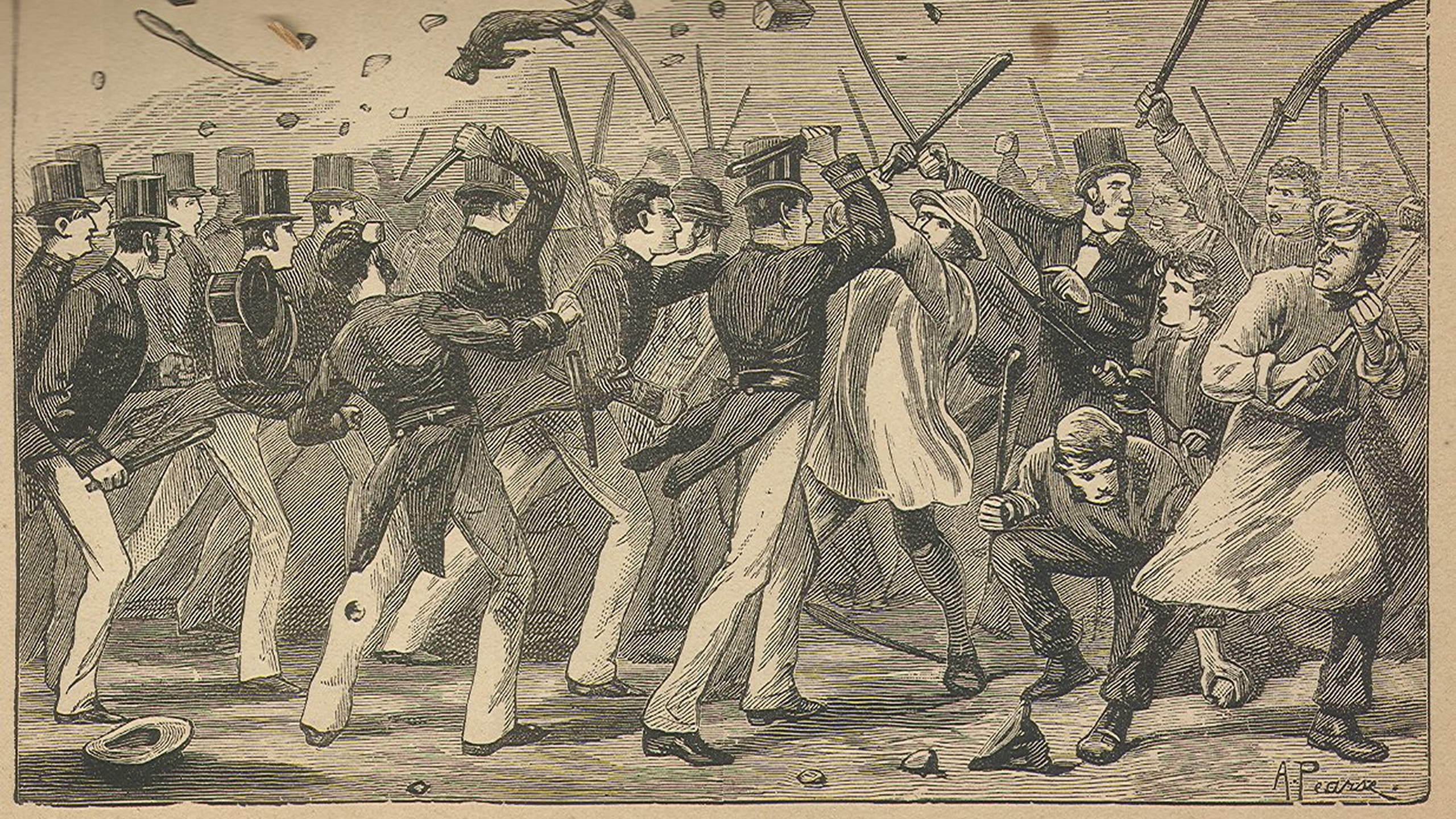

The rise of industrial capitalism brought exploited classes of people together, in workplaces and cities, like never before in history. The enclosure of land that people had lived and survived on forced them into wage labour in the smoky factories of expanding cities, to churn out huge profits for a developing bourgeoisie. And this, as Chris Harman argues, ‘provided [workers] with possibilities of resistance greater than those open to any previous exploited class – and it was resistance that could encourage the growth of ideas opposed to existing society in its entirety.’1 The 1800s was a time of intense class and anticolonial struggle. Mass demonstrations, direct action and strikes came in wave after relentless wave as the exploited classes struggled for parliamentary representation, better working and living conditions and an end to slavery. The cavalry, empowered to use lethal force, was still used to manage working class revolt and enforce public order. This was to have disastrous consequences in the 1819 Peterloo Massacre, when the cavalry charged into a crowd of 60,000 demonstrators, killing 15 of them. Far from subduing the protesters, the murders made their spirit more unwavering and ferocious: lethal force was clearly not a reliable weapon against working class resistance.2

In 1824, the government repealed legislation that banned strikes and picketing in the hopes this would quell the latest wave of workplace resistance and direct action. But it had the opposite effect, spurring on a fresh wave of strike action. The tools the state had been relying on to protect itself and capital were faltering. Revolution was in the air and as fear and anxiety bled through all sections of the ruling class, Robert Peel was finally successful in convincing the political establishment of the need for a domestic, state-funded police force. Having practised, developed and refined policing strategies in the Irish colonies, these tactics of coercion and control ‘boomeranged’ back to the mainland: Peel’s Metropolitan Police Service was founded in 1829. From its very inception, the Met has used coercive (but largely non-lethal) powers to control the organised collective potential of the working and exploited classes. This hasn’t stopped being a core part of their function today: from Black radical activism in the 1970s and ’80s, to the miners’ strike,, and environmental activism, as well as the Stephen Lawrence justice campaign, police have worked to criminalise, destabilise and repress movements for social change, in a bid to protect and maintain the state and status quo.

The tools available to the police for the daily work of enforcing the law equips them with coercive powers. These powers allow them to exercise immense control over ordinary people: arrest, stop and search, detainment, raids, restraint, physical force, strip-search, dispersal, surveillance. It’s in this way that the tools of policing differ from those of other emergency services: while the fire services, for example, centre preserving and protecting life, policing exerts coercive power over it. Yet while policing powers differ drastically from other emergency services, they are remarkably similar to the coercive and controlling tactics employed by domestic abusers. Where perpetrators search phones, police search pockets. Where perpetrators use their hands and feet, police use batons and tasers. Where perpetrators prevent their partners from leaving the house, police arrest, cuff and detain. Where perpetrators track their victims using mobile devices, police put people on tag. Even the narratives used to justify police power mirror those of abusers: ‘We do it for your own good’; ‘You make us do it’; ‘We do it because we care, even if it hurts you.’

Detective Chief Constable Maggie Blyth believes, and we agree, that the power afforded to police to control others means ‘there will be some attracted into working in policing, because of the powers that it offers them, the powers to exert and coerce other people, particularly vulnerable individuals.’ PC Frank Pulley, DS Derek Ridgewell, PC Joshua Savage, PC Wayne Couzens – these are the names of police officers now well known for enjoying the thrill of wielding coercive and controlling power over vulnerable people. But in each case, these officers were ‘aided and abetted’ by colleagues who not only enabled, but in many cases, actively facilitated their violence. Wayne Couzens, who killed Sarah Everard, was known by colleagues as ‘The Rapist’. Several colleagues were caught sharing racist and misogynistic messages with him. Colleagues knew he exploited women, after a sex worker turned up to his station demanding he pay money he owed her. In all cases, his colleagues did nothing. Relevant to this is the fact that policing is a permanent institution that employs permanent staff as part of a permanent state structure. This means it has a strong interest in protecting its own existence. It is also made up of employees who, since the 1918 Metropolitan Police strikes which shook the ruling class, have had their loyalty bought by successive dramatic wage hikes.3 These facts create a push factor towards self-preservation and internal camaraderie, and a pull factor away from accountability.

It’s for these reasons we go further than DCC Blyth, as it’s not simply the case that policing attracts coercive and controlling people. The very foundation of policing is coercing and controlling the working class; policing culture is built on the legitimacy of exerting power over others and all officers act on the belief there are some whose status in society means they are deserving of it. Policing doesn’t just attract, but creates coercive and controlling people, leaving its mark not only on the world but also on the officers who participate in it. When custody sergeant Kurtis Howard ordered the strip-search of Koshka Duff after she was arrested for handing a teenager a know- your-rights bust card, female officers jeered and laughed as they perpetrated state-sanctioned sexual assault against her. Those women may not have entered the police force with the attitudes and behaviours of abusers, but they sure will come out of it with them.

And it’s here we see that although Sarah Everard was not herself working class, her murder emerges out of the dynamics of coercion and control that underpin the maintenance of a class society, and the violent disciplining of working class people. And it’s also here that Sarah’s and Mark Duggan’s murders converge: as police violence against Black people and police violence against women both come out of the violence needed to maintain the status quo exactly as it is – and this violence will always punch downwards along lines of gender, race, ability, sexuality and class. It’s this historical analysis that grounds us in a politics of solidarity, a marked divergence from the politics of competition that has consumed many social justice movements today.

The domestic and sexual violence sectors have done important work over the years to spotlight the central role coercive and controlling behaviour plays in patterns of interpersonal violence. But the women’s sector has viewed coercion and control through the largely individual lens of violence between a man and a woman. The transition from grassroots women’s refuges to a complete reliance on state funding – which puts limits on how organisations can campaign – has made a systemic critique of wider political, economic and social dynamics impossible. Close partnership working with police and prisons in the women’s sector has obstructed a structural critique of these very same institutions, and how they reproduce coercion and control at every level of society: in the home and on the streets. As the running and funding of women’s services becomes increasingly tied in with the running and funding of police services, the critique that policing itself is coercion and control, that police are the perpetrators, seems a distant relic of the grassroots feminist organising that created refuges in a time long gone by.

This is why abolition of state policing does not mean replacing it by building up community policing. There have been new, grassroots, youth and Black-led community initiatives like Forever Family that sprung up after the 2020 BLM protests. These groups, recognising the fact that policing is inherently violent and that police don’t keep us safe, seek to address community safety by offering practical alternatives such as community-led patrols. As a result of their grit and determination, groups like Forever Family have a lot of traction in working class Black communities. But we would go further, arguing the issue is not the type of policing but the practice of policing itself. In this, we find more seeds for a revolutionary approach to abolition. On the one hand abolitionists need to address, as Sarah Lamble argues, ‘the conditions in which people feel that police are the only or best option for responding to harm in their lives’.4 Given these conditions, the pragmatic work of collectives like Cradle Community who are building responses to harm outside of violent institutions is vital. They are developing transformative, empathetic, community responses to harm, that encourage us to not just act beyond policing but think beyond policing. The work of groups like these provide a glimpse of our collective capacity to build an abolitionist future. But alongside this abolition must also be underpinned by an anti-capitalist, class analysis and practice. One that seeks to leverage class power in order to abolish the underlying conditions that give rise to a society that requires the control of the masses – the working and under classes – by the few in the ruling elite. This is the revolution in the abolition.

This is Thesis Five of Abolition Revolution, which is published by Pluto Press. New Socialist £3 and above subscribers can get 35% off Abolition Revolution and any other books from our comrades at Pluto.

-

Chris Harman. 2008. A People’s History Of The World. London: Verso. p. 323. ↩

-

Audrey Farrell. 1995. Crime, Class and Corruption: The Politics of the Police. London: Bookmarks. ↩

-

Owen Jones. 2014. The Establishment: And How They Get Away With It. London: Penguin. ↩

-

Sarah Lamble. 2021. ‘Practicing everyday abolition’, in Edited by Koshka Duff. Abolishing The Police. London: Dog Section Press. p. 148. ↩