EDITION: CLASS.

On the 50th anniversary of the National Conference of Trade Unionists Against Racism, its wide-ranging deliberations need to be recognised.

The late 1960s and early 1970s witnessed a series of “immigrant strikes” in Britain, confronting racist wage hierarchies as well as such indignities as segregated workplace toilets. These disputes were concentrated in the metal-bashing factories of Birmingham and textiles mills of Lancashire and the East Midlands, where conservative craft cultures encouraged exclusionary practices among white trade unionists. In these industries, poorly-paid Indian and Pakistani workers had been recruited in large numbers for “unskilled” roles, in contrast to the government policy of “dispersing” West Indian workers in smaller crews within especially the transport and services sectors – where they nevertheless took collective action against racism, most famously during the Bristol Bus Boycott.1

While immigrant strikes challenging racial discrimination in the face of trade union hostility have rightly “entered the labour movements’ chamber of horrors”, they also catalysed new anti-racist alliances.2 Defying the racial division of labour which separated Asian and Afro-Caribbean workers at the point of production, activists from Britain’s former colonies began uniting under a Black political umbrella, based on shared experiences of racism as well as anti-imperialist ideas of “Third World” solidarity. The formidable Indian Workers Association (Marxist-Leninist)3, which liaised with Malcolm X in Birmingham in 1965, brought ideas of Black political power into the industrial sphere.

Anti-racist strikes further gave rise to local solidarity networks, typically taking the form of “motley” coalitions of white communists and Trotskyists, Black and Asian militants, student radicals, and sympathetic elements in the broad trade union left. As Sheila Rowbotham reminds us, in Britain the protest spirit of the new left was not, as is so often assumed, absolutely cut off from the labour movement.4 The heady politics of the sixties, when social revolution was in the air, made its mark on industrial conflict and indeed prompted a rethinking of the composition of the working class.

A watershed episode was the strike at Mansfield Hosiery Mills in Loughborough, a market town between Nottingham and Leicester, in 1972 – a year when militant action by miners, builders, and dockers shook the Conservative government of Edward Heath. The dispute’s highlighting of enduring trade union racism cast a dampener over what had been a “glorious summer” of class struggle in Britain. From November to December, Indian and Pakistani workers at Mansfield Hosiery walked out over their relegation to the lowest-paid roles. Discrimination in the workplace was compounded by press-fuelled racism against Gujarati Asian refugees from Uganda, a number of whom settled in the East Midlands. In the absence of solidarity from their white co-workers, the 400-odd Mansfield strikers were forced to take independent action for their rights and dignity, and a common slogan they used was “We will not go back like dogs”. Challenging oppressive stereotypes of passivity, Asian women played a leading role, occupying the offices of the hosiery and knitwear workers’ union – which eventually succumbed to pressure and made the strike official.

Whereas in the West Midlands the Indian Workers Association (IWA) was able to utilise its links with the Communist Party and leverage Broad Left influence through the Birmingham Trades Council, in the East Midlands a new grassroots coalition emerged. Nottingham was the original headquarters of Tariq Ali’s International Marxist Group (IMG), which had kickstarted the Vietnam Solidarity Campaign. Together with leftist university students, individual trade unionists, and members of the IWA and Pakistani Friends League, the IMG collected funds and formed a strike Solidarity Committee in alliance with the local Black People’s Freedom Movement, led by the late Bennie Bunsee – an enigmatic South African Maoist of Indian descent, who acted as advisor to the strikers.

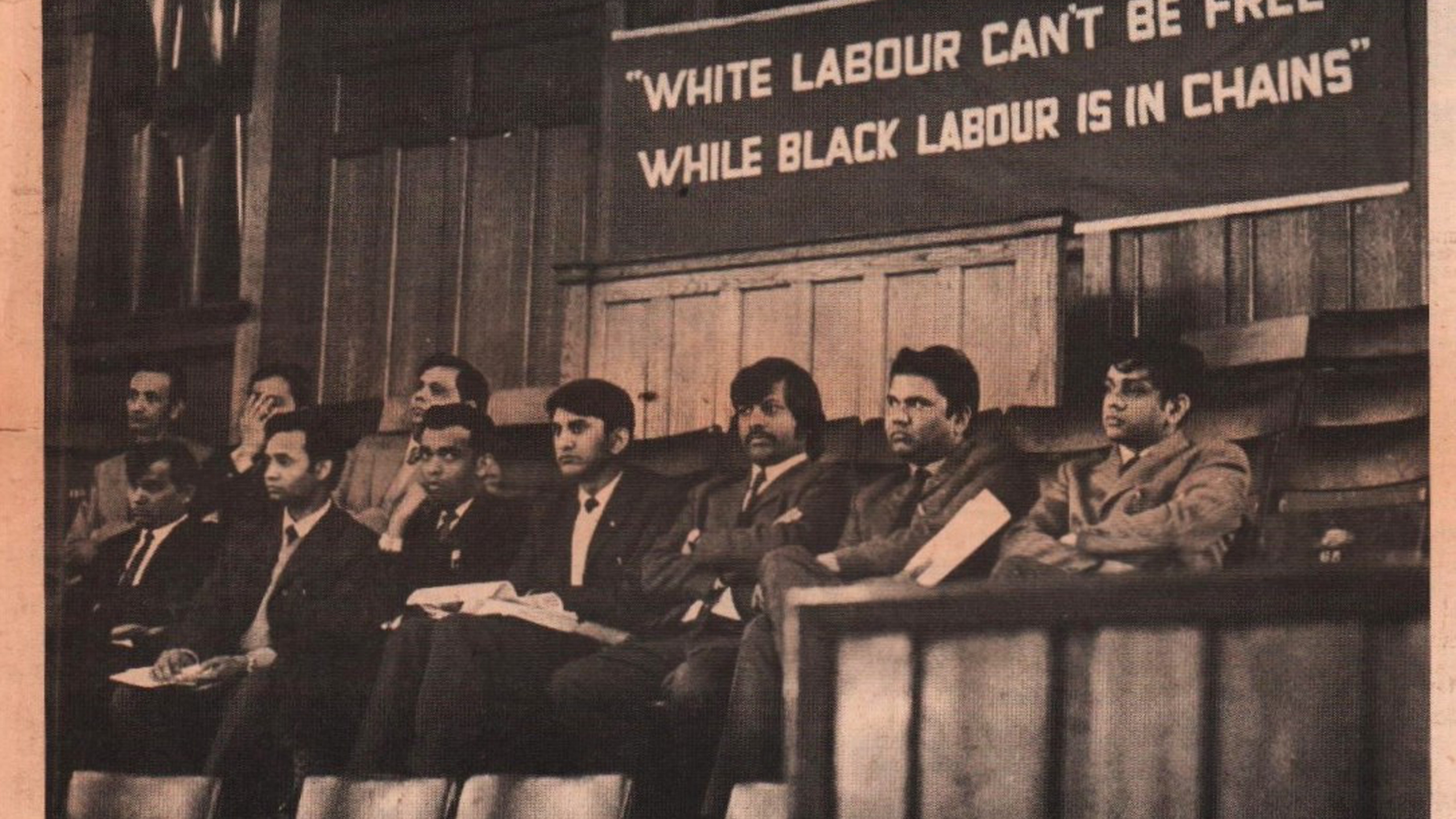

The Loughborough dispute would have wider implications for the labour movement, when the Mansfield Strike Committee called a National Conference of Trade Unionists Against Racism that was held in Digbeth Civic Hall, Birmingham on Saturday 2 June 1973. Chaired by Bunsee, it was attended by an impressive 350 people including delegates from 26 trade unions and 11 trades councils. This was despite objections from the Trades Union Congress which had received alarmist reports from district officials referring to subversive “agents of Black Power”, “Young Communists”, and “Trotsky Cell[s]”. Photos from the day show a diverse group of old and young, men and women, Black, white, and Asian attendees. A large banner placed behind the speaker’s podium was emblazoned with Karl Marx’s dictum, that “WHITE LABOUR CAN’T BE FREE WHILE BLACK LABOUR IS IN CHAINS”. There has been virtually no commemoration of this significant event and its wide-ranging deliberations, aside from a brief mention in Sivanandan’s iconic account of Asian and African-Caribbean struggle in Britain, From Resistance to Rebellion. On the 50-year anniversary of the conference, it’s time this oversight is rectified.

The importance of conferences for political consciousness raising has been underscored in the context of the postwar Women’s Liberation Movement, but less attention has been given to how trade unionists were collectively addressing new political questions. Earlier in 1970 a symposium on “The Trade Union Movement and Discrimination” had been held at the Ruskin working-class education college in Oxford, with lectures by university deans, academics, and union higher-ups – quite a contrast to the decidedly grassroots gathering in Birmingham. This article, based on an interview with a participant along with workshop papers archived in the Modern Records Centre at the University of Warwick, looks at how the Birmingham forum involved sophisticated – and contentious – debates on Black self-organisation which reverberated across the trade union movement. Attendees grappled with questions of anti-imperialist solidarity and strategic alliances in a national climate of encroaching state authoritarianism and far-right mobilisation.

Race, Class, and Black Autonomy

Opening the Birmingham conference, the erudite Bunsee outlined the many obstacles the Mansfield Hosiery strikers had to overcome in their isolated battle against workplace racism. An address from the most prominent speaker of the day, the assistant general secretary of the Amalgamated Engineering Workers Union (AUEW) Ernie Roberts, noted that the Trades Union Congress’s leg-dragging on anti-racism “is unfortunately a reflection of our movement. The TUC has a job to do and it is not doing it. It can only be made to do it as a result of pressure from below.”5

The meeting was remarkable for facilitating dialogue between trade unionists, the radical left, and Britain’s militant Black Power movement – which was taking an increasing interest in class struggle. Indicatively, the London-based British Black Panthers, who led high profile campaigns against police violence and harassment, rebranded as the Black Workers Movement in 1973 and offered their support to the Mansfield strikers. Farrukh Dhondy, later of the Race Today Collective, had introduced fellow Panthers to E. P. Thompson’s The Making of the English Working Class in order to educate members about the history of the native labour tradition and “who [they] were talking to.”6 In Birmingham, the Black Workers Movement presented their ideas for bridging the anti-racist and industrial struggles to the attendant trade unionists:

- Mobilising the strength of the whole black class in the community and in the factory.

- Seeking to talk directly to the white workers and demanding they support our struggles (as we give ours) in their own class interest. But refusing to concede to racist hostility if they refuse.

- Internationalising our struggle wherever possible.7

The conference explored questions of how racism impacted on class consciousness, and the role of immigrant organisation outside of the existing trade union machinery. Though “Black” self-organisation was promoted by the Birmingham-based Indian Workers Association, it also encouraged its members to join established union structures. For local communist and Transport & General Workers Union (T&GWU) official Don Higgs, the IWA had demonstrated in practice “that there were no contradictions” in this dual strategy. The autonomous Mansfield strikers’ committee likewise endeavoured to participate in the broader movement, and insisted they were part of “one brotherhood [sic] in the struggle for the improvement in their working conditions”. Despite this, many on the left expressed concern that Black Power amounted to “racial separatism” that divided the working class. A particularly hostile response came from the orthodox Trotskyist Socialist Labour League8, who decried the “Stalinists” and “revisionists” who they claimed had organised a “profoundly anti-working class one-day debate” in Birmingham.

Countering such ideas, Bunsee’s Black People’s Freedom Movement criticised attitudes “which oppose the formation of autonomous Black organisations and which instead view the struggles of Black peoples in a mechanical way – i.e. that it is all part of a common class struggle and therefore black peoples must join either one of the white organisations.” While all workers are exploited, the lived experience of class was not the same, and racist attitudes and oppression needed to be tackled before a genuine unity could be spoken of. Bunsee’s position was supported by his comrades in the International Marxist Group, which had a “head start” on these questions through the Fourth International’s engagement with the Black struggle in America. A workshop paper presented by IMG member Julian Atkinson argued that notions of the anti-racist “splitter” or Black “racist” stood reality on its head:

They assume that the working class is at present united. In fact, the working class is disunited and it is only the conscious efforts of socialists that can overcome the contradictions inside the working class … it is a split when groups of White workers accept this as natural or even desirable.

Another neo-Trotskyist grouping, the International Socialists (forerunner of the Socialist Workers Party), similarly agreed with Bunsee that “black workers could win if they were determined enough and that outside support from socialists was vital because of the lack of help from trade unions.” The stance dove-tailed with the International Socialists’ perspective on building socialism from below, which ascribed special importance to unofficial “wildcat strikes” circumventing the union bureaucracy – although the group’s insistence that Black and Asian workers should join its own rank-and-file networks was not always well received.

Predictably, the conference was not without controversy. Roger Tanner, another IMG member who was also on the Mansfield Solidarity Committee, remembers “there was a lot of questioning on both sides”. In the opposing position, the general secretary of the foundry workers’ union (formerly AUFW), Bill Simpson, presented a paper that warned: “The danger in this situation would be that a militant, coloured organisation, however right and justified they may be, would inevitably invoke a backlash of racial reaction from some sections of the white population in this country.” To prevent such a backlash, Black and white workers needed to unite to make the workplace and the union “truly and peacefully multi-racial.” While expressing a commitment to anti-racism, Simpson neglected the recent history in the metal foundries, where the exclusionary practices of the craft-based AUFW – dominated by “skilled” white workers – was only overcome through a decade of autonomous organising by the Indian and Pakistani shop floor movement.

Trade union exclusion was frequently justified with Eurocentric assumptions about Black and Asian workers’ immaturity, as with the Socialist Labour League’s suggestion that “groups of immigrant workers without traditions of class or trade union organisation fall into the trap of blaming white workers”. Leading IWA members in fact had a lengthy experience of socialist organising in the countries of their birth, and brought with them traditions of class militancy which were rather alien to postwar Britain! Despite enduring scepticism from certain quarters, there was, nevertheless, “quite a deal of support” by the day’s end for the idea of Black caucuses within unions – a demand which gained momentum over the following decade.

Divisions also materialised within the Black Power camp. A London-based Maoist grouping, the Black Unity and Freedom Party, was giving out flyers entitled “Black People Don’t Allow Yourself to be Fooled by the So-Called Left in This Country”. It contained a warning on the pernicious nature of the “white left”, and argued that “[i]f they are really concerned let them work at a grass roots level talking to their own workers, not holding conferences and meetings where certain officials mouth certain things”. This intervention drew a response from the Black Workers Action Committee (BWAC), co-formed by Mansfield strike leader Jayant Naik who was a Gujarati engineer from Tanzania. Reporting on the conference, the BWAC Newsletter conceded that “up to recently most white left-wing organisations in Britain opposed the formation of black organisations. Black Power was interpreted by them as meaning black racialism.” Nonetheless, BWAC argued that without allying with “responsible sections” of the white left “we will isolate ourselves … [a]nd it is only in struggle that the revolutionary left will develop. We have to strengthen our own ideas, unite firmly under a single revolutionary banner and force the white left in an anti-imperialist direction also in support of our peoples in Africa, Asia, and Latin America.”

Workers Against Imperialism and Fascism

This stress on anti-imperialism was another key theme of the conference, and left-wing internationalism had been galvanised in the late 1960s by opposition to Harold Wilson’s odious foreign policy in Vietnam, South Africa, and Ireland.

While imperialism might appear remote from the concerns of trade unionists, for immigrant workers from the former Empire issues of political coercion and economic exploitation in their countries of birth were an intimate concern. More than this, imperialism had made its mark within British society, sustaining poisonous ideas of white superiority and bolstering class-collaborationism. Bunsee’s closing remarks at the conference noted the strength of the anti-imperialist viewpoint that “the struggles of Black peoples in Britain is part of the struggles of the peoples of Africa, Asia and Latin America, and that imperialism is the cause of racialism. It was pointed out that the working classes in Britain had more in common with these struggles than it had with its own ruling class.”

Opposition to this focus on imperialism came once again from the Socialist Labour League, which had kept aloof from the Vietnam Solidarity Campaign. For the SLL, acknowledging the international dimensions of exploitation amounted to claiming that socialism at home was “hopeless” because “British imperialism had trained workers to despise coloured [sic] people.” On the contrary, the anti-imperialist position stressed the need for class unity in a period of capitalist crisis, whilst also recognising that colonialism had left its deep imprint on many British workers – reflected in the broad support for Powellism – and that this reality needed to be confronted. As the Association of Communist Workers emphasised, “racial discrimination cannot be completely eradicated while the system that gave rise to it still flourishes; it is therefore in the interests of the working class, both black and white, to fight against imperialism.”

These questions surrounding the causes of racism within the labour movement at a time of economic downturn were given immediacy by the resurgence of far-right activity, including fire-bombings of Black residences and community centres. Another conference speaker was the future founder of anti-fascist magazine Searchlight Maurice Ludmer, a Jewish trade unionist in USDAW and veteran campaigner against the segregationist “colour bar” in Birmingham. During the Mansfield strike, an article titled “Put Britain First” by a National Front member was published in the Hosiery and Knitwear Workers Union bulletin, and Ludmer noted that the NF “has made no secret of its determination to win over and influence sections of the working class”. The government’s inaction underlined “the crucial importance of the working class creating its own bulwark against fascism and against racialism.”

Street-level racism fed upon encroaching state authoritarianism, and another Jewish socialist in attendance, Steve Cohen, penned a paper highlighting the government’s convergent attacks on immigrant communities and organised labour, in the context of Heath’s Industrial Relations Act which sought to legally shackle workers’ shop floor organisation. Discussing the rightward drift in Britain, Cohen warned that the labour movement ignored anti-Black police oppression at its own peril. He pointed out that the ruling class’s ability “to systematically pick off black militants who are on the fringes of the labour movement” with little resistance had given them the confidence “to hit the centre of that movement in the shape of, for instance, the Shrewsbury pickets” (a reference to workers arrested during the builders’ strike in 1972, including Ricky Tomlinson). The international dimension of fascism was further highlighted by Álvaro de Miranda of the T&GWU’s Portuguese workers’ branch in London, representing migrant service workers from Southern Europe, who drew attention to Britain’s ties with the Salazar dictatorship – a final bastion of direct colonialism in Southern Africa.

Many of the same themes were taken up at subsequent Conference of Trade Unionists to Combat Racism in London – this time an initiative of the Communist Party, which historian Evan Smith shows was “shocked out of complacency by the events at Mansfield”.9 A leading role was played by National Union of Teachers member Winston Pinder, a Lenin cap-wearing Barbadian who had organised alongside Claudia Jones in the Black response to the Notting Hill riots. On 22 July, delegates from a total of 41 branches across 15 trade unions assembled at NUFTO Hall in Holborn (the old headquarters of the furniture makers’ union), and the Birmingham conference’s steering group was also invited. It was noted optimistically that several Trades Councils had already set up sub-committees against racism. However, a speaker from the umbrella Black Workers Co-ordinating Committee cautioned against complacency and reminded delegates that, in light of growing fascist agitation, the “slogan of ‘Black and White Workers Unite’ was meaningless where there was visual and practical evidence to the contrary.”

As at the Birmingham meeting, tensions were registered around issues of Black political power and self-organisation. Bernard Dix, a leading militant in the National Union of Public Employees, referred to hostile letters in Tribune attacking the London-based Trade Unionists to Combat Racism and “claiming that such an organisation would drive workers into Powellite camps.” Dix pointed out how such claims ignored existing roots of division, and how “this country’s imperialist and colonial history has left many white workers believing that black and immigrant workers are second class”. He called for unions to roll out remedial political education. At the close of the meeting – which ended early to enable attendees to join an anti-deportation protest in Southall – a plan of action was drawn up, including to organise for the repeal of racist immigration laws, and to “make it known to the trade union movement the true history of Asia, Africa and the Caribbeans and South Americas”. Pinder concluded the conference on a fighting note of anti-racist class unity:

Now the talking is over and it is time for action. We have a programme which can arm us for action. Black and White both need each other, for if it is the Black workers in the morning, it will be the White workers at noon.

Lessons: Difference and Solidarity

So, what was the legacy of these landmark meetings where trade unionists discussed anti-racist strategy and debated Black Power? Roger Tanner concedes that the conferences did not fully live up to their own ambitious objectives. The International Socialists complained that “the [Birmingham] conference failed to make clear exactly how socialists were to fight racialism in the working class. It could do no more than issue calls for action—it could not organise.” Though a National Committee of Trade Unionists Against Racism was formed which included Bunsee, Naik, Mike Cooley (Maoist architect of the antimilitarist Lucas Aerospace Plan) and representatives from both the Communist Party and IMG, it soon fizzled out, as evidenced in the paltry attendance at an anti-fascist summit it called the following year. The inability to sustain itself as a movement reflected ideological differences on the left, as well as among the various Black socialist formations. It should also be noted that women were largely unrepresented at the conference, although there were pledges “to fight against the growing exploitation of Indian women in industry”.

There particularly remained a hesitancy by the Communist Party leadership and more orthodox Trotskyist groups to acknowledge the legitimacy of Black autonomy, which caused tensions during the subsequent Imperial Typewriters dispute in Leicester – where a youthful Asian striking workforce took collective action independently from the local Transport & General Workers Union under the right-wing grip of George Bromley. Nevertheless, various socialists, communists, and Black and Asian radicals still co-operated in the broad left Inter-Racial Solidarity Campaign, which forged a genuine community of resistance against fascist reaction in the city.

Above all, the conferences were catalysts for transformations in trade union attitudes. As Bunsee declared, the Birmingham forum was “the first of its kind in the history of the Labour Movement in the country”, and “a watershed in the struggle against racialism.” The political demands which were articulated reverberated into the upper echelons of the labour bureaucracy, and were brought to the annual Trades Union Congress in Blackpool. The Congress reported that the issues raised at Mansfield Hosiery were “by no means over”, and 1974 marked official TUC acknowledgement for the very first time that “trade unions should actively oppose racialism within their own ranks”. That same year, the T&GWU issued the rank-and-file pamphlet Racialism, Fascism and the Trade Unions with a foreword by general secretary Jack Jones – the face of a reinvigorated labour internationalism – and uncredited contributions from conference attendees Atkinson and Tanner arguing in favour of Black self-organisation.

The impressive trade union solidarity displayed in 1976-8 during the celebrated Grunwick strike led by Jayaben Desai has gone down as an iconic episode in Britain’s working-class history. However, as Azfar Shafi and Ilyas Nagdee highlight, the triumphalist narrative isolates Grunwick from a longer arc of anti-racist struggle, peppered with antagonisms, setbacks, and conflicting strategies. For instance, some Black activists criticised the Grunwick strikers’ dependency on official trade union structures, which left them especially vulnerable to the TUC sell-out.10 Sivanandan lamented how “[t]he lessons of the earlier strikes – that black workers needed to rally the community behind them and from that base force the unions to their side – had been temporarily unlearned by workers who had not had the benefit of that tradition.” Similarly, whilst Black or “BME” committees now exist in the major trade unions, the origins of the drive for self-organisation grounded in revolutionary anti-racist politics are often forgotten. Into the 1980s, the Black Caucus Movement became associated with the municipal radicalism of the Labour left-run Greater London Council, and although issues of imperialism and workers’ power remained on the agenda, over time representation increasingly became an end in itself. In the words of one pessimistic scholar, “Black” workers “became heirs to the institutional sclerosis of the British labour movement”.11 Plus ça change: progress is rarely linear, or uncomplicated.

This article has also challenged equally simplistic renderings of the postwar British labour movement as implacably conservative and aloof from the “new social movements”: a stereotyped image that has been promoted by intellectual currents, such as those identified by Sivanandan, that appear all too eager to bid “farewell to the working class”. For all its flaws, the labour movement proved to be capable of at least partially overcoming the (real) training in racism which imperialism gave to white workers. In a present context where identity is so often counterposed to class – and autonomy absolutised/derigged from perspectives on building anti-capitalist alliances – it is important to remember the reality of a period which saw “a more complex relationship with ‘difference’”; where tensions over race, class, gender, and sexuality were “discussed, debated and recognised”.12 Collectively addressing contradictions within the labour movement, not least the role of imperialism, did not further fragment the class struggle but, on the contrary, strengthened its binding “political seams”.13

-

In instances where Afro-Caribbean workers were concentrated in low-paid areas of factory work, notably in the large motor assembly plants like Ford Dagenham and Longbridge in Birmingham, similar strategies of Black self-organisation were adopted. ↩

-

John Wrench. 1986. Unequal Comrades: Trade Unions, Equal Opportunity and Racism. Centre for Research in Ethnic Relations, University of Warwick. p. 3. ↩

-

The “Marxist-Leninist” reflects the split in the Indian Workers Association, with the IWA(M-L) aligning with the Communist Party of India - Marxist Leninist and supporting the peasant uprising in Naxalbari against the Communist Party of India - Marxist, who did not. ↩

-

Sheila Rowbotham. 2001. Promise of a Dream: Remembering the Sixties. London: Penguin Books. p. xiii. ↩

-

Roberts later participated in the launching of the Anti-Nazi League. ↩

-

Anne-Marie Angelo. 2018. “‘Black Oppressed People All Over the World Are One’: The British Black Panthers’ Grassroots Internationalism, 1969-1973”. Journal of Civil and Human Rights. 4:1. p. 22. ↩

-

Ron Ramdin. 1987. The Making of the Black Working Class in Britain. Aldershot: Gower Publishing. p. 366. ↩

-

“Orthodox Trotskyism” refers to the SLL’s adherence to the original Transitional Programme of the Fourth International. For a critique of the orthodox Trotskyism of the SLL, see Duncan Hallas’s “Building the Leadership”. ↩

-

Evan Smith. 2017. British Communism and the Politics of Race. Leiden: Brill. p. 150. ↩

-

Azfar Shafi and Ilyas Nagdee. 2022. Race to the Bottom: Reclaiming Antiracism. London: Pluto Press. p. 43. ↩

-

Mark Duffield. 1988. Black Radicalism and the Politics of De-industrialisation: The Hidden History of Indian Foundry Workers. Aldershot: Gower Publishing. p. 177. ↩

-

George Stevenson. 2016. “The Women’s Movement and ‘Class Struggle’: Gender, Class Formation and Political Identity in Women’s Strikes, 1968–78”, Women’s History Review. 25:5. p. 742. ↩

-

A. Sivanandan. 1985. “RAT and the Degradation of Black Struggle”. Race & Class, 26:4. p. 1. ↩