Rescuing the memory of past working-class struggles, like Telford’s ‘Cinderloo’, can kindle political commitment for the present and future.

We study the past not in order to find out what really happened there... but to find out what it takes to face a future we should like to inherit rather than one that we have been forced to endure.

Hayden White

Peterloo, you probably know about. But Cinderloo … what’s that?

You won’t have heard of Cinderloo because it’s just one of capital’s tiny wars: an overlooked battle between miners and their bosses that exposes industrial capitalism’s underside; merely one of the grubby chains leading to our smooth, seamless world of one-click ordering and contactless credit cards, a baby step to a “world market society”.

Yet down in the cracks and seams of global capitalism lie working-class voices that demand a hearing. Just as detectives gather evidence and witness statements to re-imagine a crime, so these voices might help us regain the empathy missing from histories written on capital’s upper deck, and provide the fresh perspectives lacking in a time of soundbite politics, fake news, and the pseudo-outrage of faraway media and political elites.

The problem is not only the rescue of forgotten voices―just as historian E.P. Thompson famously sought to rescue “the poor stockinger, the Luddite cropper, the ‘obsolete’ hand-loom weaver”. The problem lies in creating the social space where such voices can be represented, received, and responded to. What is required are less the tools of the historian than the scythe of the populist, the ear of the musician, and the tenacity of the organiser to connect past struggles to today’s problems. Because with zero-hours contracts, the gig economy, and the monopoly power of giant corporations driving down wages, it’s clear that millions of us, in the words of working-class historian Studs Terkel, endure “jobs that are too small for our spirits”. Likewise, a hollow time of food banks and austerity pushes us toward stories that speak of resistance, and ring true.

This is the story of a rescue, its reception, and the response: the making of a situation, and a case, called Cinderloo.

In 1815 the Napoleonic Wars end – the conflicts by which the English, Welsh, and Scots first identify themselves as ‘Britons’ – and the British economy slumps. The first of the Corn Laws, passed in the same year, drives up the price of bread and other foodstuffs—with the resulting destitution in the north of England leading to public unrest and the Peterloo massacre of 16th August 1819.

With falling demand for iron, and with competition from newer works in the Black Country and South Wales, ironmasters in the East Shropshire coalfield, in illegal combination, decide to force a wage reduction on workers in early 1821. When the wage reduction is announced in late January, workers call a strike. On the 1st February, with colliers on strike at the pits, ironworkers in the north of the coalfield bring production to a dead stop. Having seen off an attempt to cut wages the previous year, workers in the coalfield are in a militant mood and, backed by their community, ready for a fight.

February 2018. A cold, windy night in Dawley, just one of the former industrial villages which make up today’s Telford New Town. A poster, a few words on Facebook, a couple of phone calls, and thirty-five people arrive at the first meeting at the Elephant and Castle pub.

Glancing around the pub there are all sorts: local historians, geologists, trade unionists, librarians, workers, retired workers, carers and cared for. A few artists, musicians and poets too. Political views diverge, but we’re all here for Cinderloo, a forgotten event in local working-class history from nearly 200 years ago. Social theorists might call Cinderloo a “boundary object”, something around which groups of people can associate without having to agree; a project where everyone can take a piece and find a place; a spark and a starting point.

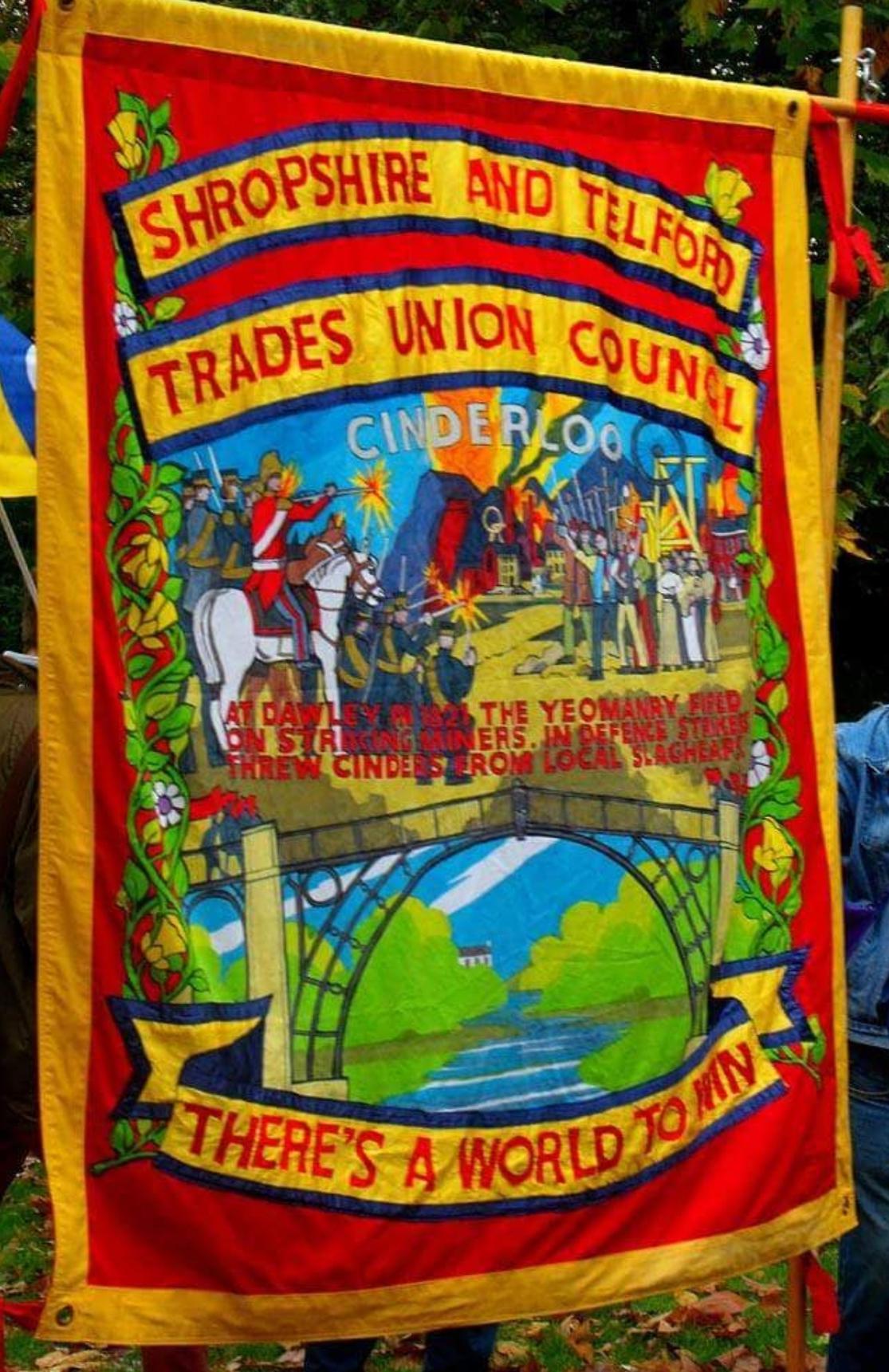

It’s certainly sparked people’s imagination. Tim’s produced a logo, Jill has her camera—anyone mind being filmed? Joy’s traced a death certificate. Ted’s written a ballad. Marcus is doing the Facebook group. Jason’s written a song. Gemma has the local trade union banner. Three retired miners from the Granville pit, the last working local mine closed in 1979, raise funds for a memorial to miners killed working in Telford. “Dig deep for the miners!”

What else? We need a constitution. Pete’s got one. We need a website, Andrew can do that. Oh, better have a bank account in case anyone wants to give us money. Meeting is over in an hour. The next two hours we spend talking, making new friends, collaborating and plotting. Oh I forgot. John, the pub landlord, has put on a Cinderloo Palin ale. Going down a treat.

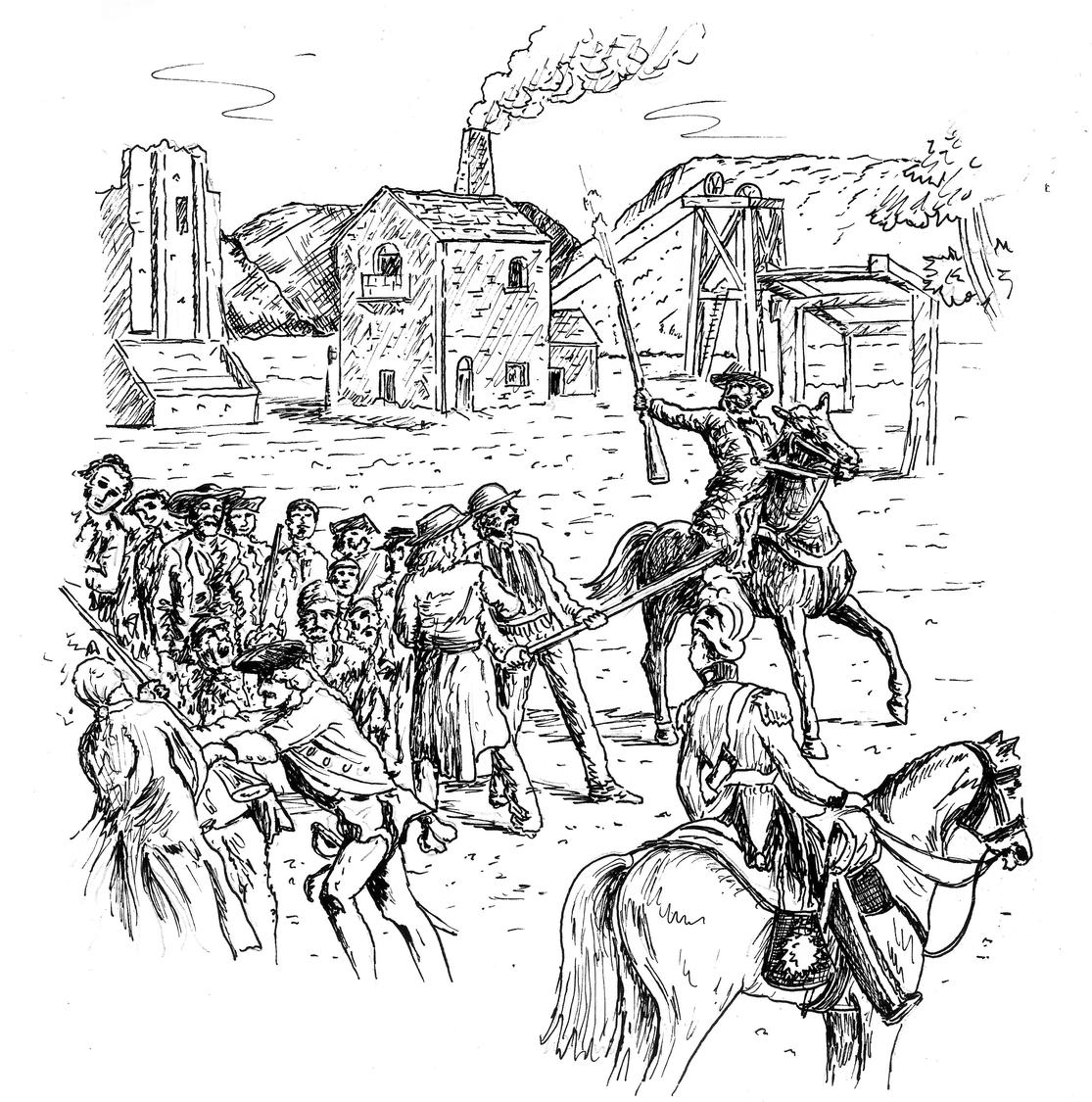

On February 2nd 1821 workers march to the southern part of the coalfield to close it down. Around 400 of them stop production at several local ironworks by shutting down the furnaces, before heading to Coalbrookdale, the centre of iron-making in the region.

They get part-way there. The yeoman cavalry and special constables are on their trail so they turn north again. The crowd has swelled to over 3000, with women and children joining them. They reach Old Park, site of the Botfield ironworks – Thomas Botfield being one of the ironmasters behind the wage reduction – and a large group climb the heaps of waste slag and cinder there, the cinder hills. Two ringleaders are arrested. The people on the cinder hills rain down stones on the magistrates, constables, and cavalry gathered below. A collier, Thomas Palin, leads a charge to rescue the two arrested men. The crowd pull the men away…

Next meeting: October 17th 2018. The evening that Mike Leigh’s Peterloo premieres in Manchester. Ted’s poem echoes in the background as photos flash up on the wall showing a Cinderloo campaign that’s angered and engaged people in equal measure; showing a recent walk to where the fight between the authorities and miners took place, a walk cut short by a security guard confronting the thirty-five-strong greying local ‘mob’.

We also see a GPS map of the original site, an offer from The Battlefields Trust to research the area, and photos of school kids learning about Cinderloo and its place in local history. Martin shows the film he’s made, with a song narrated by Malcom in his Dawley accent, and charcoal drawings from Mike. The meeting erupts in applause. Concepta points out there needs to be more women. Martin says “Right, get people to record something on their phones, send them to me and I’ll draw it.” Job done.

Pete mentions the recent Uber strike and how things haven’t changed 200 years on: piece-work, zero hour contracts, and no trade unions. Gemma suggests we all march behind the TUC Cinderloo banner at the upcoming local protest against NHS cuts. All those in favour? Agreed.

A lottery bid is submitted to support work with schools. Two parish councils have donated £1300 and the Annual General Meeting will be in February with music, poetry and an art exhibition.

Panic erupts. The yeomanry open fire on the workers killing eighteen-year-old collier William Bird. Another collier, Thomas Gittins, later dies from his wounds. Many others are also wounded, as is Thomas Palin, who is shot in the arm. After visiting a local doctor he is arrested.

An inquest is held into the deaths, returning a verdict of justifiable homicide. There are arrests and then a trial. Samuel Hayward is sentenced to death, but later reprieved. Seven other colliers get nine months in jail on a charge of riot. Thomas Palin is tried for felonious riot, convicted, and hung by the neck on 7th April 1821 in the yard of Shrewsbury prison. Someone from the watching crowd shouts out “Farewell, Tom!” His body thrashes in the spring air for several soundless minutes, before being cut down and handed to friends.

Home Secretary Lord Sidmouth writes to the Lord Lieutenant of Shropshire praising “the patience with which the yeoman cavalry bore the insults of the rioters”. The miners’ wages are reduced. A community smashed to its core turns inwards, embracing various Methodist sects to salve its wounds.

Every town has its Cinderloo. A case of wrongful imprisonment, the breaking of a strike, the combination of rich against poor, a community hurled into poverty. In his 1972 essay ‘A Special Case’, E.P. Thompson invites us to think through such events when he writes:

It is never safe to assume that any of our history is altogether dead. It is more often lying there, as a form of stored cultural energy.1

Thompson reminds us that there are no special cases. Cinderloo, Peterloo, and the thousands of capital’s tiny wars—from the matchgirl strikes to McDonald’s walkouts—are just the “stored cultural energy” that history ignores; the raw material of change; the precious ore waiting to be discovered, mined, and brought to the surface. Capital’s tiny wars continue to take place in the dark, as they always have; but many also lie waiting to be gathered, kindled, and ignited by an enthusiastic and spirited few.

-

E. P. Thompson, Writing By Candlelight (1980) ↩