Though a relatively forgotten figure today, renewed hostilities between Labour's left and right make the story of Reg Prentice's bitter divorce from the party newly relevant.

Pious references to the Labour Party being a 'broad church' which has always incorporated many different strands of thought fail to take account of a crucial fact, namely that the 'broad church' of Labour only functioned effectively in the past because one side – the Right and Centre – determined the nature of the services that were to be held, and excluded or threatened with exclusion any clergy too deviant in its dissent.

Ralph Miliband, ‘Socialist Advance in Britain’ 1

Among the ranks of Labour’s extensive rogues’ gallery, some names in particular remain deeply and painfully etched into the party’s collective folk memory. Ramsay MacDonald, Oswald Mosley, the Gang of Four: all of these continue to inspire varying degrees of odium among Labour partisans to this day.

One such rogue, infamous in his day but whose memory has since largely receded into the mists of time, is Reg Prentice. In 1977, having been deselected by his local constituency Labour party after a protracted and gruelling media row, Prentice took the decision to defect from the Labour Party to the Conservatives, with Thatcherism in the ascendant and the decrepitude of the post-war social-democratic consensus apparent for just about all to see.

Prentice’s defection was a major headline-grabber at the time, not just because of his status as a veteran Labour frontbencher but also because of what it reflected: namely, the deepening divisions within and mounting strains on the party’s ‘broad church’. With the pressures of Britain’s economic, political and social crisis bearing down on Labour, no longer could its radical socialists and its mild social reformers both shelter under the same roof in quite the same way as they had when the going was relatively easy.

In his biography of Prentice,2 Geoff Horn notes that he “remains the most high-profile political defector between the two main British political parties in the post-war period”. Though a relatively forgotten figure today, the renewed hostilities between left and right in the Labour Party means that Prentice’s story (along with Horn’s study of it) is again newly relevant.

The Crisis in Revisionism

To understand how the Prentice saga came to pass, we have to go back a further two decades. Hugh Gaitskell’s rise to the Labour leadership in 1955 marked a major sea-change for the party. Gaitskell, of whom Prentice (who would enter Parliament two years later) was a loyal supporter, was riding the crest of a wave: that of social-democratic revisionism, a political tendency which was at this time gaining markedly in strength. With a heritage in the Labour Party dating back to the 1930s and, before that, in the ‘new liberalism’ of the early 20th century,3 Gaitskellite revisionism soon set about calling into question the very fundamentals of Labourism as an ideology (its urtext in this regard being Anthony Crosland’s The Future of Socialism) and also as a political culture.

The relative intellectual torpor both of traditional moderate Labourism and also Bevanism during these years further fuelled the rise both of Gaitskellism and also of the first New Left, which emerged partly in response to Bevanism’s stagnation.4 This New Left would, for a time, engage in a curious but critical exchange with the revisionist social democrats. While there was some common ground between the first New Left and the Gaitskellites in their shared scepticism of traditional Labourism and their desire to rethink socialism in changed conditions, the New Left (and in this it was soon vindicated) could not share the revisionists’ faith in the ‘mixed economy’, nor could it agree that this represented the sort of fundamental social change which revisionist intellectuals like Crosland had claimed for it.5

Though Gaitskell himself died in 1963, it was Gaitskellite doctrine that continued to serve as the intellectual and strategic basis of Harold Wilson’s government from 1964-70.6 That basis was soon to be found badly wanting in robustness. Wilson’s election to the leadership had initially been welcomed by many on the Labour left (Wilson having been a former Bevanite), but they were to be bitterly disappointed: as one Labour MP later put it, this turned out to be the period in which “the grass came away from the roots”.7 The trouble for the revisionists was that they were the ones who were forced to bear the brunt of the frustration about Wilson’s failures in office, and they would prove unable to marshal any convincing defence of the government’s record as its critics in the party grew more vociferous.

Prentice, who served first as education secretary and then as minister for public works during Wilson’s first spell in government, had started out as a fairly middle-of-the-road revisionist, but the deepening crisis radicalised him to the right, leading him to ask fundamental questions about the direction of his party and the nature of the alliances on which it was founded.8 As the 1970s wore on and with the Labour left making real advances, Prentice became increasingly uneasy at the political shifts which were taking hold in the labour movement – with the New Left establishing a firm foothold within the party and growing militancy among the trade unions, which as shadow employment spokesman Prentice came to see as a genuine threat to the rule of law9 – and took it upon himself to inspire the Labour right into launching a sustained counter-offensive.

But the revisionists, by this time, were in no fit state to mount one. As Horn points out, another problem facing the revisionist right (and Prentice, in his efforts to rally it) was that after years of dominating the commanding heights of the Labour Party and setting its policy agenda, it had become somewhat flabby and complacent, both intellectually and organisationally.10 Not only had the revisionists allowed the strength of their factional machine to deteriorate, but they could also offer no convincing rebuttal to the criticism they had received, lacking as they did any explanation for why the first Wilson government had fallen so far short of the expectations loaded upon its shoulders. As a consequence, the Labour left’s intellectual critique and its policy prescriptions continued to gain in credibility and purchase among the party’s activists.

Radhika Desai highlights a more fundamental shortcoming which the revisionists had failed to address.11 Though they had set themselves the goal of supplanting orthodox Labourism with a new social-democratic doctrine better adjusted to the conditions of the post-war, welfare-state era, the Gaitskellites “hardly played any significant mobilising or pedagogic role in the labour movement”, nor did they devote much energy to building up organised rank-and-file support. They were thus reliant on the right-wing trade-union machine to buttress their control over the party, a dependence which, while it sustained them at Labour’s helm, effectively “stalled and denatured the revisionist doctrine as the price of their continued leadership”. This ideological impasse was demonstrated by the Gaitskellites’ failed attempt to replace Sidney Webb’s Clause IV in 1959, which was seen off not by a Bevanite fightback but instead by “a groundswell of Labourist sentimentality”.12

When the trade unions started to shift leftwards from the late 1960s, the revisionists were marooned high and dry as they no longer had a solid bulwark against the challenge being mounted against them from the left. Their intellectual brio having deserted them at around the same time, they were – to compound matters further – soon to find themselves left ideologically adrift by a crisis of capitalism which none of them saw coming or knew how to address, their previous assumptions of benign prosperity and a steady, serene ascent to social justice discredited. This would set a good number of them on a trajectory that would lead them out of the Labour Party altogether, though it would take some longer to reach this conclusion than others.

The Broad Church Breaks Up

Never one to be taken in by the mythology surrounding Labour’s ‘broad church’, Ralph Miliband recognised that its left and right wings stuck together in the same party (by and large) more due to realpolitik than anything else. Well aware of how first-past-the-post erects such sizeable barriers to entry for new parties, and of how it tends to punish splits, the divergent tendencies contained within the Labour Party – whose disagreements were always far more than the mere narcissism of small differences, however arcane they might often have appeared to outsiders – were condemned to a seemingly inexorable jockeying for position against one another. Talk of a ‘broad church’, in this context, never amounted to much more than an unconvincing attempt at post-hoc rationalisation.

Miliband singled out the role of those “prominent ex-members of the Labour Party” who have taken it upon themselves to launch vociferous attacks on it once it is perceived to have exceeded certain boundaries of legitimacy; “the burden of the message remains constant: the left is a menace”. The eagerness with which many Labour or ex-Labour politicians have volunteered themselves for this role has proven “very useful to the forces of conservatism” over the years. Not only that, but this enthusiasm among the Labour right for using its easy media access to do as much damage as possible to people who are (nominally) on its own side has rarely been reciprocated by dissident Conservatives, as ruthless as these might sometimes be in dispatching their own leaders:

There are very few instances of the same service being rendered to the forces of change by Conservative or ex-Conservative ministers and other leading Conservative figures. Such people rarely denounce Conservatism, or their former friends and colleagues, or Conservative activists, or the Conservative Party, with anything like the virulence and bitterness of their Labour counterparts.13

Reg Prentice, as his isolation from the rank and file of his party grew, was not lacking in either virulence or bitterness towards them. Back in opposition after 1970, first as Labour’s shadow employment spokesman and then as shadow education secretary, Prentice angered many in the party with his outspoken refusal to support labour movement cause célèbres of the period. One such instance was that of the Shrewsbury Two, a pair of trade unionists imprisoned for ‘conspiracy to intimidate’ while picketing during a construction industry dispute in 1972.14 Forming as their trials did part of a wider government offensive against militant trade unionism, Prentice’s unwillingness to back the Shrewsbury pickets infuriated trade unionists and many party members alike. Prentice, who believed that legislation passed by Parliament was totally sacrosanct regardless of the intent behind it or its effects in practice, also attacked the Pentonville Five for flouting Ted Heath’s Industrial Relations Act (scorning the notion that they were “latter-day Tolpuddle martyrs”).15

The Labour right at this period was growing more and more nervous about Marxist influence, real and imagined, in the party and the trade unions.16 Michael Foot and Tony Benn were among those who accepted Marxism as a legitimate strand of Labour opinion, but the right tended to see it either as a sectarian imposition or as Soviet-inspired subversion (despite the numerous and quite eclectic assortment of Marxist and Marxisant views on the socialist left of the 1970s). Unable to accept that there was a genuine groundswell of socialist opinion amid mounting dissatisfaction at the inadequacies of the post-war compact, many viewed the rise of the left with great trepidation. But a return to the command-and-control bureaucratic machine which had prevailed in the Labour Party of the 1950s proved unfeasible, not least because the party leadership could do nothing (even if the will were there) about the shift to the left inside the unions.

Prentice also crossed swords with Benn (then starting to emerge as leader of the Labour left, steadily superseding Foot) over industrial policy, opposing the proposal contained in Labour’s Programme 1973 to nationalise 25 leading industrial monopolies.17 Harold Wilson likewise had no intention of ever implementing the policy, which had been approved by the left-moving National Executive Committee, and made it clear that the shadow cabinet would exercise its veto if it were pushed into doing so. While, in the event, the vagaries of the conference compositing process killed off the 25 monopolies policy by yoking it to an unpalatable proposal from Militant to nationalise 250 firms, Wilson had also refused entreaties from Prentice and Shirley Williams to publicly disown it. Its defeat at conference left behind a lingering, sulphurous aftertaste and made it abundantly clear to party activists the disdain in which their views and concerns were held by many Labour frontbenchers and MPs – Prentice prominent among them.

The upheaval that had gripped the labour movement had caused Prentice to consider whether or not the different strands of the Labour coalition were fundamentally compatible any longer. He was far from the only one to have similar doubts. Gaitskellite MP Dick Taverne, deselected by his constituency party in Lincoln, had quit the party and retained the seat in a subsequent by-election in 1973. Horn also recounts that Roy Jenkins, an ally of Prentice, had expected Labour to lose the general election of February 1974, and intended to launch a challenge for the party leadership once that outcome transpired.18 But it didn’t, and Jenkins’ well-laid plans were reduced to rubble; he reluctantly returned to his former role of Home Secretary, where previously he had been one of the most enduring success stories of an otherwise frustrating six years for the first Wilson government.

Jenkins’ divorce from Labour proved agonising and took almost a decade to play out: he had been approached by Taverne in 1973, for example, “to use the Lincoln campaign as the catalyst for launching a new social democratic party”. Jenkins was personally hesitant about wading into the conflict that would inevitably follow and declined the opportunity, nor did he want to go down in Labour history as “a latter-day Ramsay MacDonald”. Prentice’s persistent disputes with the trade unions and with Wilson caused Jenkins to step in and warn the latter that if Prentice were sacked from the cabinet, he would follow. But Prentice was becoming increasingly convinced that Labour was predicated upon “an untenable coalition of incompatible political forces” and, though dismayed by the lack of dynamism displayed by his fellow right-wingers, still aspired to form a centrist, cross-party national government.

This idea enjoyed strong support from The Times, which in the winter of 1973-4 mounted a campaign calling for a national government consisting of centrist Tory and right-wing Labour figures, and citing opinion polling which appeared to indicate strong public support.19 While Wilson and Heath distanced themselves from the proposal (Heath would later come to support it), it led to renewed discussions about the possibility of coalition government in forcing a broader political realignment. Leading Labour revisionist John Mackintosh concluded after discussions on the matter that “a new centre party led by Jenkins was the preferred choice of senior establishment figures”; this hypothesised centre party was already being talked about as a future bulwark in “depriving a more left-wing Labour Party of power”. Dick Taverne was among those who took to the pages of The Times “to press the case for a realignment of the centre-left” during this period.

Tendencies towards cross-party centrist collaboration were strengthened by the Common Market referendum campaign of 1975. Harold Wilson suspended collective cabinet responsibility for the duration, allowing Jenkins to line up alongside the likes of Heath and Jeremy Thorpe in full view of the public; an experience all concerned appear to have found quite congenial. As Desai notes, the referendum campaign thereby exacerbated the centrists’ “disaffection with the current division of the parties” and “in providing a foretaste of possibilities, sowed the seeds of future rupture”.20

For the ardently pro-European revisionist Labour right, Desai adds, the referendum campaign also underlined just how vast was the chasm separating them from the bulk of their own party, whose activists very largely opposed Britain’s presence in the Common Market. Though Prentice had originally shared Gaitskell’s Euroscepticism, which had for a period put some distance between him and his revisionist colleagues, he had come around to supporting Common Market membership by the time of the referendum – albeit anticipating that a victory for the pro-Marketeers would trigger a split in the Labour Party and drive them into a coalition government with Heath.21 However, Prentice’s potential coalition colleagues on either side of the Commons divide continued to dither and vacillate. Key Jenkins supporters including Shirley Williams and Bill Rodgers, who hadn’t yet given up hope that their man might win the leadership, sought instead to maintain a semblance of unity in the Labour Party while working to foster a renaissance of the revisionist right within it.22

The rise of Margaret Thatcher to the Tory leadership, meanwhile, meant that the would-be coalitionists were deprived of a more companionable Conservative leader in Ted Heath. Yet Tory centrists preferred to wait and see where Thatcher was taking them, instead of mounting an offensive against her leadership and political philosophy,23 an offensive for which they would have been ill-equipped anyway. When it came to the crunch, the ideological differences between Tory ‘wets’ and ‘dries’ were not of the same magnitude as those dividing left and right in the Labour Party. Once momentum had swung properly behind Thatcherism, the Tory ‘wets’ (who were, like their revisionist counterparts in Labour, rendered intellectually inert by the crisis) meekly acquiesced to it with little more than some ineffectual carping along the way, and slowly but surely were all but extinguished as a distinct political tendency.

Despairing of the lethargy of his allies, Prentice stepped up his efforts to highlight the untenability of Labour left and right’s continuing cohabitation, in a last-ditch effort to prompt the breakaway he felt was necessary to prevent a future left-led Labour Party from forming a government, and to shore up the stability of parliamentary democracy itself.

Nowhere Left to Go

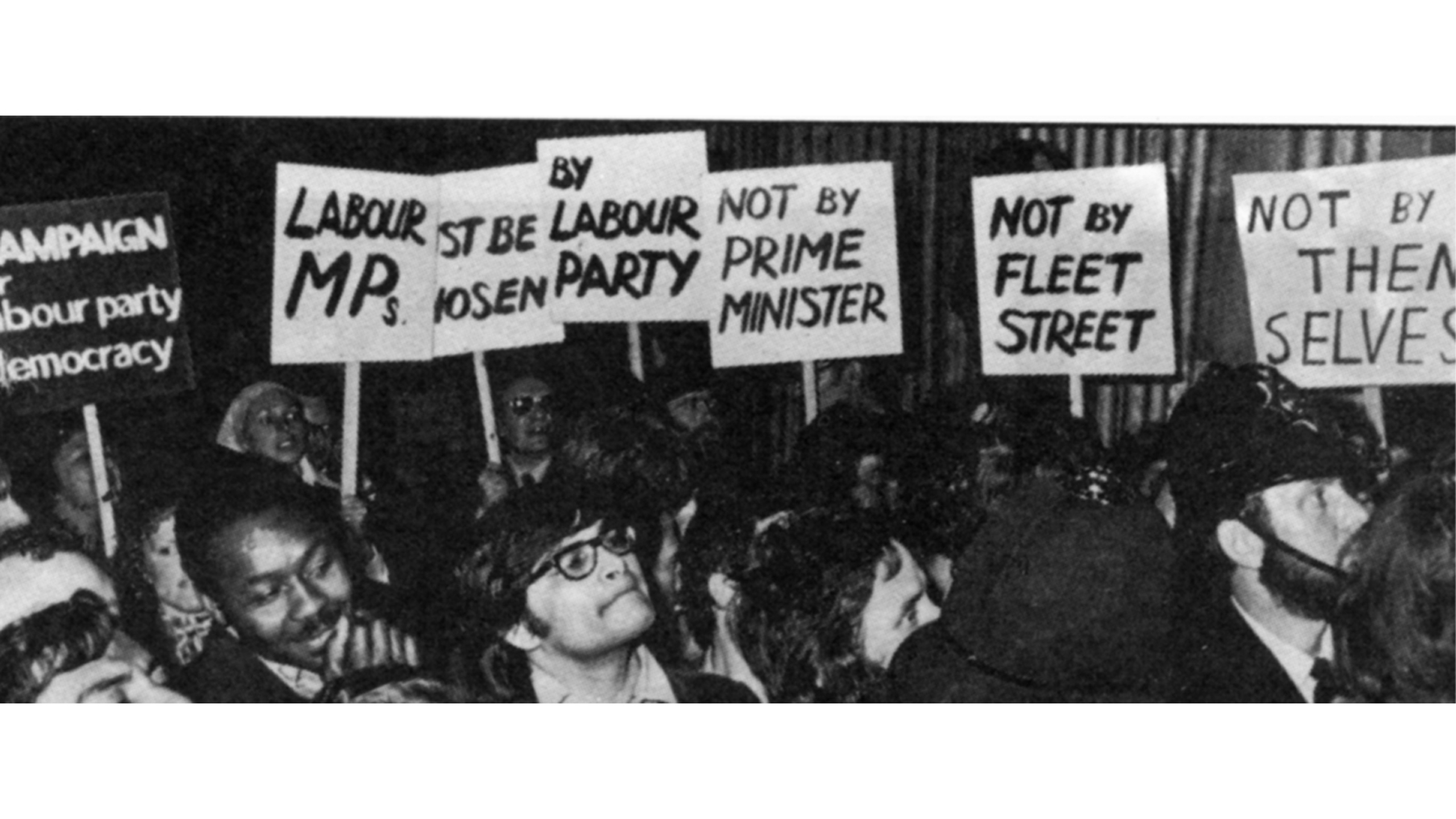

Frustrated activists in Prentice’s CLP, Newham North East, took matters into their own hands. Some local members having sought Prentice’s removal as Labour candidate since 1973, favourable changes in the political composition of the local party ultimately enabled them to pass a motion at its General Committee in July 1975 calling on him to retire at the subsequent general election.24 Prentice, in keeping with his self-appointed role as tribune of the persecuted Labour right, had no intention of allowing himself to go quietly: instead, he opted to turn his deselection into a media circus. His aim in doing so was to highlight the unsustainability of Labour’s ‘broad church’ while painting the left as intolerant, at the same time elevating himself into a martyr of moderation.

The role of Militant in Prentice’s deselection was hyped up in some subsequent accounts (not least by Prentice himself), but its actual presence in the constituency party was a modest one.25 Rather than being a sectarian plot as some on the Labour right preferred to believe, the leftward movement in Newham North East CLP was, as Horn puts it, “representative of the national trend in similarly safe, but semi-moribund Labour seats”. Nevertheless, Prentice and his supporters in the press were keen to portray constituency activists as foaming extremists, with lurid details of one local left-wing member’s personal life paraded across the front page of the Daily Mail in an effort to discredit him.26

While the press and politicians continued to cast around for conspiracies, the influx of New Left activists at this time was changing constituency Labour parties across Britain – many of which were badly hollowed out by the late 1960s – beyond recognition, while the ‘old guard’ of more traditionalist party members was ageing and becoming less active. Horn observes that these members were thus less equipped to assemble any rearguard action in defence of threatened right-wing MPs like Prentice, who were also deprived of the backing they had once enjoyed from a phalanx of right-wing trade unions and the interventionist National Executive of yesteryear, always keen to prevent deselection rows.

Prentice’s parliamentary private secretary, Neville Sandelson (later to defect to the Social Democratic Party) sought instead to drum up support for Prentice within the Parliamentary Labour Party.27 Along with ally Michael Ward, Sandelson drafted a letter which was to be sent to Prentice’s CLP imploring it to reconsider the course of action upon which it had embarked, citing pluralism and Prentice’s track record of public service in his defence. In total, 181 Labour MPs put their names to the letter; Hilary Wainwright has contrasted this show of solidarity with the PLP’s disinterest in the earlier deselection of left-winger Eddie Milne, who fell foul of the Tyneside Labour machine and was dropped as Labour candidate for Blyth after challenging the corruption of T. Dan Smith, and all to near-total silence from his parliamentary colleagues.28

But the support garnered by Sandelson and Ward’s letter prompted other right-wing MPs to join the fray in defence of Prentice, among them actor-turned-MP Andrew Faulds, who issued dire and appropriately theatrical proclamations about the advances within the party of far-left infiltrationists. Harold Wilson, though unimpressed with some of Prentice’s tactics and with little love lost between both of them, eventually threw his own weight behind his minister, even to the point of threatening to personally intervene and overturn the deselection if it went ahead.29

Nevertheless, Prentice was defeated at the all-important constituency meeting of July 1975, and as it turned out, Wilson’s warm words of reassurance weren’t worth the hot air that carried them. Prentice came out swinging after losing the vote, talking publicly about his plans to appeal to the NEC and appealing to ‘moderate’ Labour supporters to join the constituency party in order to ensure that it was “more representative” of local opinion.30 However, in private, events in Newham North East CLP had confirmed him in his view “that a social democratic breakaway party was both necessary and inevitable”. He would thereafter redouble his efforts to draw attention to the fundamental incompatibility of Labour left and right, in the hope that more of his colleagues on the latter wing of the party would draw the appropriate conclusions and follow him out of it.

Prentice pondered his next move. He mulled the possibility of calling a by-election and running as an independent against the official Labour candidate, and privately explored options for getting other parties to stand aside so as to ensure a one-on-one contest (which were quickly scotched by Conservative Central Office). Elsewhere, Horn notes, Roy Jenkins and his key allies still remained reluctant to force the issue of a split, anticipating that an impending economic crisis would serve in effect as deus ex machina in splitting the major parties and bringing about the realignment they were hankering after.31

In 1976, with the International Monetary Fund winging its way to Britain, Harold Macmillan intervened to express his own support for a cross-party coalition government (conscious of the delicate nature of Labour sensibilities in this area, he was careful to stipulate 1940 as his preferred precedent rather than 1931).32 Sections of the Tory parliamentary party expressed support publicly and privately for the idea and revisionist Labour MPs including David Marquand and John Mackintosh were suspected of being sympathetic, but both Callaghan and Thatcher were unreceptive. The Labour left was especially hostile to the idea, its suspicion being that the different sections of the political centre were banding together in one last effort to prop one another up like drunks staggering down the street at closing time, and in so doing shut the socialist left out of government, perhaps for good. Nor was the Thatcherite Tory right, which saw its own opportunity to radically change Britain glittering before it, any more enthusiastic about coalition. Both Labour left and Tory right, then, were in agreement insofar as they saw coalition as “yesterday’s idea preached by yesterday’s men”.33

That same year, Wilson resigned, and Jenkins contested the ensuing Labour leadership election with no serious expectation of winning, even though some of his supporters thought they might be able to unify the right and centre around them to beat Michael Foot in the final run-off.34 However, the PLP instead rallied behind the more amiable James Callaghan. Jenkins could only muster 56 votes in the first ballot; stung by his rejection, he departed for Brussels to serve as President of the European Commission in January 1977. Prentice was retained as minister for overseas development, but his most important ally in the cabinet was gone. Despite Callaghan’s display of confidence in the threatened Prentice by keeping him in his post, and the indication it represented that the right “was more clearly in charge of the Labour Government than it had been under Wilson”, Prentice proceeded with his abrasive and confrontational approach, believing that the Labour coalition was still unsustainable whatever sticking plasters were applied.

With both the Labour left and Tory right simultaneously in the ascendant, however, the prospects of actually assembling a cross-party centrist coalition that could command a majority in the House of Commons were minimal.35 The Lib-Lab pact which sustained the Labour government in office during 1977-78 was not, as Prentice had originally hoped, a precursor to a new age of more consensual and less tribal politics, but was instead an arrangement forged “out of political expediency rather than principle”. Continued appeals for a centrist national unity government to ride to the rescue appeared more and more as a desperate effort by an obsolete political establishment to shore up a consensus that had visibly reached the end of the road. Even if such an administration had somehow been lashed together, given the absence of any dynamic new thinking from within it on how to resolve the crisis, it is unlikely that it would have governed dramatically differently from how Callaghan’s Labour did.

Prentice, with some reluctance, started to face up to the reality that the two-party duopoly in Britain was not likely to be dislodged any time soon. But the Labour right was itself starting to speak a similar language to the Thatcherites. Callaghan’s 1976 speech to Labour conference laid out the impeccably neoliberal logic underpinning his government’s austerian turn, with the IMF breathing down its neck. Horn suggests, reasonably enough, that it is quite likely that a Callaghan government, had one been returned at an early general election in the autumn of 1978 (as was widely anticipated at the time), would have taken a “neo-revisionist” direction, embarking on “limited privatisation” and tax cuts.36

The problem that would have confronted Callaghan, however, was that neither the party nor the trade unions, both already approaching the end of their tether with the government’s social contract, would have sat quietly by while he did so. Callaghan would therefore have been faced with the unappealing task of steadily rolling back the gains of post-war Labourism and inevitably tearing the labour movement apart in the process, the whole thing unravelling perhaps even more spectacularly in government than it eventually did in opposition. Resolving the crisis on the terms of British capital (with which Callaghan was not prepared to tangle) required a drastic diminution in trade union power, which only a government unabashedly of the New Right could deliver.

For Prentice, however, the die was already cast. His efforts to force a realignment had failed to pick up any real momentum, and his potential allies on either side of the Commons sat on their hands. Recognising the continuing stranglehold of Labour and the Tories on British political life, and the fact that only either one of those parties could realistically ever lead a government, Prentice was not interested in joining the Liberals either – instead favouring a “straightforward choice” between the major parties.37 By now, Prentice’s disaffection was not just with the left but with the whole post-war social-democratic compact, which was evidently exhausted. Though stopping short of a wholehearted conversion to the monetarist and neoliberal doctrine which was rapidly becoming hegemonic in the Tory Party, Prentice found that in many areas (foreign and defence policy, support for the Common Market, the reining in of trade union rights, and so on) he had relatively little to disagree with.

His defection, when it came, left his right-wing supporters in the PLP red-faced.38 Horn observes that the Labour left indulged in no small amount of schadenfreude following Prentice’s departure, with a Tribune editorial demanding apologies from those who had backed Prentice and in doing so dragged the party through the mud. The right had little to say in response, embarrassed as it was at having defended someone who had officially confirmed himself as a turncoat (and who had been assumed to be a turncoat-in-waiting by the left for a number of years). But Prentice had been distant from the bulk of the Labour right for some time, having alienated them with his confrontational tactics and apparent predilection for showmanship. Prentice, for his part, was dispirited by what he saw as the right’s failure to fight the Labour left with the same energy it was itself being fought.

Prentice’s post-defection career, consisting of a spell as a junior minister and eight years as MP for his new constituency of Daventry, was a fairly undistinguished one. Nor was he tempted to join the Social Democratic Party when it finally broke away from Labour in 1981, whatever lingering sympathies he may have had for the endeavour. But at the confidence vote in the Callaghan government in March 1979, Prentice’s defection had already proved to be just enough to tip the scales in Thatcher’s favour – and the Labour government famously fell on the strength of just a single vote.39 Once Thatcher was securely installed in 10 Downing Street, however, Prentice had more or less outlasted his usefulness to the Tory Party already. It was the trade union right that thereafter found itself tasked with organising the counter-revolution against the Bennite left, a task which would occupy it for much of the following decade.40

Desai’s verdict that the breakaway of the SDP “marked the historic end”41 of revisionism in the Labour Party would be proved premature by the New Labour experience of the following years, and an underestimate of the strength of the roots revisionism had put down. Yet that revisionist heritage today is in a parlous, borderline moribund state. The rapid and embarrassing collapse of Change UK can only serve as a stern cautionary tale to any right-wing Labour MPs still longing for more genteel new pastures. But to give him his due, and though its crisis was ultimately deferred as the right gradually regained control of Labour, Reg Prentice’s conviction that the ‘broad church’ was built on flimsy foundations looks today like an astute one.

Whatever the next few years have in store, Labour will remain a diverse coalition of socialists and social reformers of different stripes. But it is possible for political coalitions to be diverse to the point of incoherence. The deepest ambiguities of the ‘broad church’ remain unresolved and their clarification – one way or the other – threatens to be a disorderly and damaging process, though now possibly an unavoidable one. With the media once again full of speculation about deselections and national governments, and with the Labour right and Liberal Democrats openly bonding over their shared antipathy to Jeremy Corbyn, it is a reality that today stares the Corbynite Labour left in the face, however much it tries to avoid its gaze.

-

Ralph Miliband, Class Power and State Power, Verso 1983, p300-301. ↩

-

Geoff Horn, Crossing the Floor: Reg Prentice and the Crisis of British Social Democracy, Manchester University Press 2016. ↩

-

Radhika Desai, Intellectuals and Socialism: ‘Social Democrats’ and the Labour Party, Lawrence & Wishart 1994, p49-54. The full text is available courtesy of its author here. ↩

-

David Howell, British Social Democracy: A Study in Development and Decay, Croom Helm 1976, p203. ↩

-

Patrick Diamond, The Crosland Legacy: The Future of British Social Democracy, Policy Press 2016, p180. ↩

-

Desai 1994, p66-7. ↩

-

Quoted in Lewis Minkin, The Labour Party Conference, Manchester University Press 1980, p290. ↩

-

Horn 2016, p8. ↩

-

Horn 2016, p30-31. ↩

-

Horn 2016, p57. ↩

-

Desai 1994, p105-6. ↩

-

Desai 1994, p106-7. ↩

-

Ralph Miliband, Capitalist Democracy in Britain, Oxford University Press 1982, p78-9. ↩

-

Horn 2016, p80-2. ↩

-

Horn 2016, p35-8. ↩

-

Horn 2016, p53-6. ↩

-

Horn 2016, p44-5. ↩

-

Horn 2016, p75-6. ↩

-

Horn 2016, p61-2. ↩

-

Desai 1994, p166-7. ↩

-

Horn 2016, p90-1. ↩

-

Horn 2016, p131-2. ↩

-

Horn 2016, p181. ↩

-

Horn 2016, p96-7. ↩

-

Horn 2016, p101-2. ↩

-

Horn 2016, p114. ↩

-

Horn 2016, p112-13. ↩

-

Hilary Wainwright, Labour: A Tale of Two Parties, Hogarth Press 1987, p26. ↩

-

Horn 2016, p114-15. ↩

-

Horn 2016, p122-3. ↩

-

Horn 2016, p126-7. ↩

-

Horn 2016, p159-61. ↩

-

Horn 2016, p180. ↩

-

Horn 2016, p149-50. ↩

-

Horn 2016, p179-80. ↩

-

Horn 2016, p7. ↩

-

Horn 2016, p185-7. ↩

-

Horn 2016, p198-200. ↩

-

Horn 2016, p210-11. ↩

-

See Dianne Hayter, Fightback! Labour’s Traditional Right in the 1970s and 1980s, Manchester University Press 2005. ↩

-

Desai 1994, p65. ↩