Salford Community Theatre's latest production, 'The Salford Docker', points the way to new and more engaging forms of socialist political education.

Political education on the left has always been hit and miss for me. Often it struggles to reach the right people with the right messages. It usually comes in a stale format which inspires nobody to think twice about how to change the way society is structured. It lacks innovation and ambition and it underestimates the skills within our own ranks and the appetite of those we want to involve.

In January I auditioned for a part in Salford Community Theatre’s production, The Salford Docker. I had seen their incredible debut performance three years earlier, an adaptation of Walter Greenwood’s Love On The Dole, and was jealous of the camaraderie the cast had developed. Camaraderie seems too weak a word to use for people I would now consider family. I had no idea how much my ideas about the world, about socialism, about my comrades and about myself would change during the next six months.

The outreach work done by SCT and the huge effort to recruit a cast of local non-actors, almost all of whom are not involved in organised political groups at all, was ambitious but necessary to tell the story of The Salford Docker.

The plot was especially significant to the local cast given how big an effect the destruction of the docking industry is continuing to have. The local area of Ordsall being pulled apart to accommodate shiny buildings and high rise flats in a new expensive postcode close to Media City is obviously brutal to anyone from the area. Learning about your own history or that of your family is important and valuable, and just because it’s yours doesn’t mean it isn’t important to the wider political landscape.

We learnt about the fights trade unions went through to prevent mass redundancies due to mechanisation; how the unions weren’t against technological advancement if it meant more time off for workers as opposed to unemployment. We learnt about the zero-hour contracts of the 1950s, where men had to scramble in a pen every morning to get picked to work by a foreman. We learnt about how the replacement of slums with adequate housing juxtaposed with the dented pride of working-class women who had done their best to make those slums a home.

This inevitably spurred on conversations within the cast about the work or housing issues we face today, discussions which grew in confidence over time as our understanding, and our eagerness to change the injustices our communities still face, developed.

The strongest messages the audience took from the play, and the strongest feelings the cast took away from the process of making it, were those we want to see emulated in a socialist society: solidarity, community and collective struggle. The play ends with an argument between parents; a mother who encourages her son to leave Ordsall and go to university to get a better life than they did, and a father who, through striking on the docks, learns that solidarity means not leaving anyone behind - including your family and the working class community you came from.

Throughout the making of the play, these ideals were constantly drilled into us by the directors, Steph Green and Sarah Weston. We were responsible for each other, for everyone. If anything went wrong, we would quickly get over it and work together to make it better again. We were kind and empathetic and we made sure that everyone was at their best and getting better all the time. We worked collectively, always, and we understood that solidarity means not leaving anyone behind.

Under neoliberalism, isolation is forced onto us from all angles. At work, where the Tories are destroying unions and everyone is on a different contract to stop you being able to fight for better conditions together; at home, where our houses are being replaced with high-rise flats with no chance of sitting out front and chatting with your neighbours; in our communities, where pubs and community centres are being replaced with luxury gated communities to keep the poor out. Collective responsibility through taxes for vital institutions like the NHS is quickly but quietly being dismantled to encourage individualisation which only helps the rich.

We are constantly encouraged to blame other sections of our own society for the deliberate failings of the few at the top, hardly ever stopping to think about how powerful the working-class is as a collective.

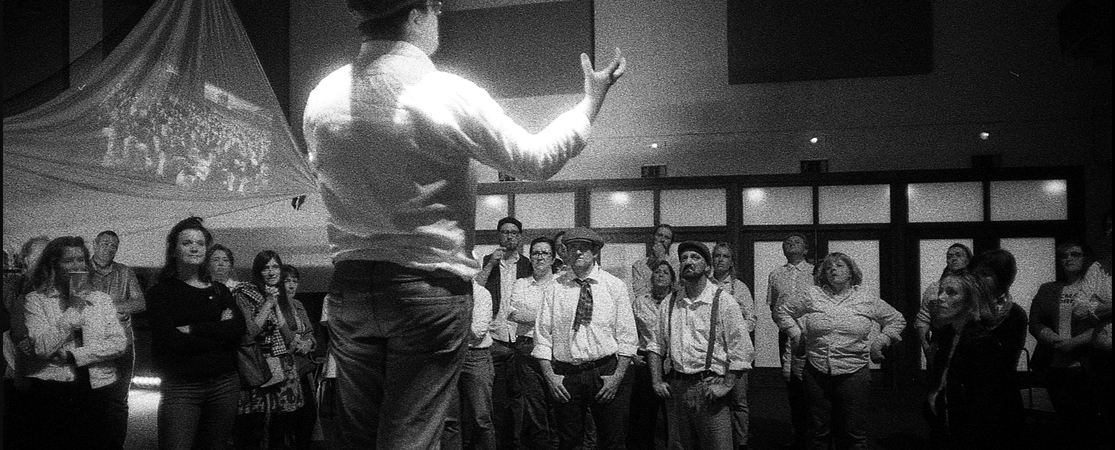

The left goes some way already to combat the increasing isolation we face, but falls short when it comes to creating our own sustainable communities as others are torn down around us. Salford Community Theatre has done this, incredibly successfully, unrelenting and uncompromising in its political message as it follows in the footsteps of communist Ewan MacColl, whose songs were woven into some of the sadder scenes of the play. A local cast of 25, who were all working normal jobs alongside, created the most special project I’ve ever been involved in, with nearly 500 tickets sold over a week.

Consciously applying socialist ideals in a practical way, trusting people to make the commitment of 6 months of work on top of full-time jobs or caring responsibilities, boasts ambition that the majority of the left couldn’t contemplate - including me, until we closed our final show. The genius of this project, of Sarah Weston, Steph Green and Salford Community Theatre must now be cause for the wider left, and especially those elements whose political consciousness extends only to the M25, to sit up and take careful notice.