EDITION: CLASS.

The enduring optimism of late 60s music contrasts starkly with the cynicism of the early 2020s—but the political parallels are striking.

We’re short on what Raymond Williams called “resources of hope”1 right now, as our dystopia merely anticipates new management. This is where music’s affective archive can come to our aid, its hauntology of history offering not just escapism but inspiration. The period evoked in this extract is an interstice between the 60s and 70s, and in a negative – and familiar – framing, represents the defiant last days of a counterculture facing its inevitable demise. Yet in my book’s framing, this period produced a tougher form of resistance after peace and love’s reason had met only reaction – culminating in Chicago in 1968 – with Black Panther and Vietnam War protest tactics inspiring the women’s liberation, gay liberation and industrial militancy that would characterise the ornery 70s. And, as always, you can hear it in the music.

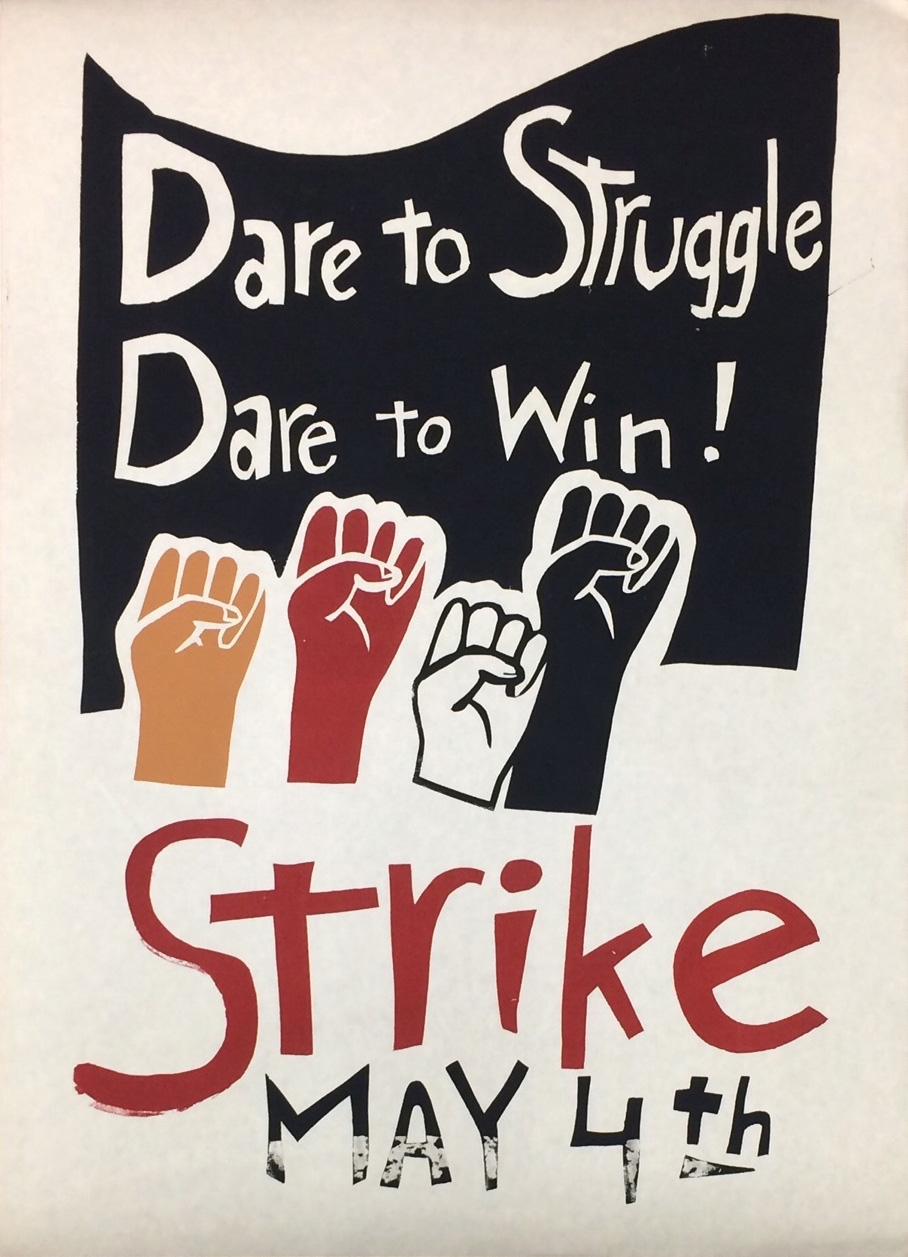

If the enduring – but calcifying – optimism of late-1960s music contrasts starkly with the cynicism of the early 2020s, the political parallels are salient: the defeat of a radical alternative followed by right-wing restoration and racist resurgence; a reasserted authoritarianism underpinned by endless imperialist war. But also: unstoppable, massed anti-war protests, embedded anti-imperialist encampments on university campuses. Now as then, marchers and demonstrators have been met with violent repression and cynical slander – called anti-Semitic, violent, naïve or performative – with centrists having long retro-fitted their own cynicism to the 60s, the integrity of such collective, solidaristic action must be discredited. Yet just as the Weather Underground held its ‘days of rage’ in October 1969, these are our days of rage, unencumbered by illusion or party allegiance, located in the streets, the campuses and the unions, and, with the late-60s’ example as inspiration, creating a platform and template for future mobilisation.

“Forces of Chaos and Anarchy”: Revolution and Restoration at the End of the 1960s (1968-71)

While the counterculture had been countered by autumn 1968, it hadn’t been crushed: while the Fordist order had reasserted control, it had been seen to flounder. Despite the conventional ‘death of the 60s’ narrative, the period from late 1968 to mid-1971 contains a striking number of countercultural highs: the 1968 Olympics’ Black Power salutes, the Woodstock festival, the trial of the Chicago Seven, the feminist disruption of 1970’s Miss World and the glory of ghetto soul. Sheila Rowbotham recalls that, “caught in that maelstrom of international rebellion, it felt as if we were being carried to the edge of the known world”.2 Yet we hear rather more about this period’s countercultural lows, what Simon Reynolds and Joy Press call “the tenor of desolation and fatalism [in] the aftermath of the 60s”:3 the Manson murders; the violence at the 1969 Altamont festival; a Black Panther declaring women’s role in the revolution “prone”; the deaths of Hendrix, Morrison and Joplin – and the breakup of the Beatles. Once the standard-bearers of 60s optimism, the Beatles’ valedictory statement was a defeatist dirge, a recommendation in such “times of trouble” to simply ‘Let it Be’ (Highest Chart Position: 2; US 1). Todd Gitlin recalls that “the riptide of the Revolution went out with the same force it had surged in… activists cooled, beaten and disappointed in the measure they were once hopeful”.4

These contradictory impulses reveal this period’s polarities after the relative cohesion and stability of the high 60s. 1968 was the apex of Fordism, the peak of post-war incomes and the apotheosis of Western economic growth.5 It was also when Fordism began to falter, real wages became a warzone and growth began to shrink. The Fordist consensus was increasingly contested not just in its actions – by the counterculture in the bloodiest period of the Vietnam War; by renewed working-class militancy – but in its essence: by capital cutting costs to compete globally; by a resurgent anti-Fordist conservatism. Hall recites the right-wing refrains of this restoration as “law and order, the need for social discipline and authority in the face of a conspiracy by the enemies of the state, the onset of social anarchy, the ‘enemy within’, the dilution of stock by alien black elements”.6 Conservatives were alarmed by Black Panther militarism and countercultural militancy – and particularly by their potential to combine,7 with Panther Huey Newton declaring, “only by eliminating capitalism and substituting it [with] socialism will… all black people achieve freedom”.8

Yet the right positioning itself as the representative of “property, family, religion, order” is, Marx argues, always a populist ruse to discredit anyone to their left as “the enemies of society”. As such, murderous hippie cultist Charles Manson was the right’s best nightmare. The ruse worked: Richard Nixon and Edward Heath’s election victories in 1968 and 1970 effected a conservative restoration by interpellating a ‘silent majority’ in opposition to what Nixon called the “coastal elites”, conflating metropolitan liberal culture and counterculture. Soon Nixon would wage a ‘war on drugs’, whose symbolic priority-shift from his predecessor’s ‘war on poverty’ pitted respectable straight society against a supposedly anarchic alternative society.

Jefferson Airplane’s claim that “we are forces of chaos and anarchy” on winter 1968’s ‘We Can Be Together’ (Volunteers, US 13) satirises such conservative attitudes: “We are obscene, lawless, hideous, dangerous, dirty, violent.” The rump counterculture’s increasingly revolutionary outlook was caught by Lindsey Anderson’s If (1968) and Thunderclap Newman’s stunning 1969 ‘Something in the Air’ (1). Lest anyone imagine “the revolution’s here” is metaphorical, the song spells out how it’ll be achieved: “Hand out the arms and ammo/We’re going to blast our way through here”. This paralleled the attitude of the Panthers, Yippies and Weather Underground – who, declaring war on the American government, bombed the Capitol Building in 1971 – and Britain’s Angry Brigade. Yet given the crackdown exemplified by 1968’s events in Chicago, the counterculture’s calcification was clearly a response to the increasingly authoritarian countermeasures of the state. As Marx remarked, “To defend oneself with a stick when attacked with a sword” is, to the establishment, chaos and anarchy. Mainstream media presented popular protest as civil disorder, and the ‘new journalism’ did the same, with added pretension. Tom Wolfe conflated revolution with counter-revolution in his ‘Me Decade’ essay, while Joan Didion claimed the counterculture to be “devoid of any logic save that of the dreamwork”, and that hippie “disorder was its own point”.9 This has become a consensus on the late 60s: Reynolds invokes “the sixties sagging into decadence”;10 Michael Bracewell laments “the significant role of violence in an epoch too frequently misrepresented by the truism ‘Love and Peace’”.11 Yet there’s no distinction in these accounts between what was done by or done to the counterculture. Indeed, Jeremi Suri uses “violence” only to describe the actions of protestors, never those of the state, while also calling the hippies’ favourite philosopher, Herbert Marcuse an “international advertiser for romantic ideas of liberation through sex and violence”.

The state may be struck from the historical record, but it struck contemporary skulls and ribcages with tangible force. California Governor Ronald Reagan declared, “If it takes a blood bath, let’s get it over with – no more appeasement”, and crushed the hippie occupation of Berkeley’s People’s Park in May 1969 (one dead) and the Isla Vista ‘riot’ in January 1970 (one dead), while an FBI raid on the Black Panthers’ HQ resulted in the “justifiable homicide” of Fred Hampton. Then the death toll stepped up. Nixon sent the National Guard against war protesters at Kent State University in May 1970 (four dead), at Jackson State days later (two dead), while police attacked the fall 1971 Attica prison protest (43 dead). Less bloodily, but equally bloody mindedly, the state also deployed black ops (the FBI’s COINTELPRO exposed in 1971) and the judiciary (the British state vs. Oz magazine; the US state vs. war protestors) to counter the counterculture, and used the legislature to tame trade unions, with Wilson’s 1969 ‘In Place of Strife’ only withdrawn under pressure. Capturing this authoritarian atmosphere, R. Dean Taylor’s 1970 ‘Indiana Wants Me’ (2; US 5) fearfully observes: “Out there the law’s a comin’… Red lights are flashin’ around me,” as bullets fly. Which were the forces of chaos and anarchy?

Tony Judt regards the counterculture as bringing this counter-revolution upon itself: “the narcissism of student movements, New Left ideologues and the popular culture of the 60s generation invited a conservative backlash”.12 Nina Simone’s 1968 ‘Backlash Blues’ (’Nuff Said, 11) captures this reaction as a specifically “white backlash”. Segregationist Alabama governor George Wallace and British Conservative Enoch Powell played on fears of the racial ‘other’ among sections of the working class that hadn’t benefited from Fordist mobility, and on the paranoia of the petit bourgeoisie who had, shifting the direction of political discourse in the wake of 1968’s Civil Rights (US) and Race Relations (Britain) Acts. Carl Freedman argues that Nixon’s ‘law and order’ campaign motif “was the dominant code phrase… for hatred and fear of blacks”,13 and with the issue also underlying Heath’s 1970 campaign (and 1971 Immigration Act), race served as a repository for a broader ressentiment about the 60s’ upending of hierarchies and habits of mind.

While popular culture reflected this resentment in reactionary, working-class Alf Garnett (Till Death Do Us Part) and his American analogue Archie Bunker (All in the Family), this tendency also testified to something progressive: the cultural power of the working class, underwritten by political power. West Virginian miners shut down the state in 1969,14 a wildcat postal strike caused Nixon to call in the National Guard in 1970, while in 1971 dockworkers on Britain’s Clyde staged a counterculture-inspired ‘work-in’ which forced the government to reverse planned closures. This class power was audible in music: Glen Campbell’s jazzy country songs infiltrated AM radio with accounts of ordinary working men, like his 1968 ‘Wichita Lineman’ (7; US 3), who’s proud of working for “the county”, or the soldier in 1969’s subtly anti-war ‘Galveston’ (14; US 4). Nicky Thomas’s 1970 reggae hit, ‘Love of the Common People’ (7) posits pride against poverty when there’s “a dream to cling to”. Lennon donated to the dockworkers, while his late-1970 ‘Working Class Hero’ raged, “You’re still fucking peasants as far as I can see” (Plastic Ono Band, 8; US 6). McCartney’s first post-Beatles single, 1971’s ‘Another Day’ (2; US 5), was derided by critics – and Lennon – for the one thing that made it notable: the depiction of a female office-worker’s everyday life. Everything, for Jethro Tull’s “common working man”, is ‘Up to Me’ (Aqualung, 4: US 7). Even Benny Hill’s 1971 novelty ‘Ernie (The Fastest Milkman in the West)’ (1) depicts ordinary working people as mythic heroes embroiled in an eternal struggle.15

For all this era’s reactionary cultural currents and the restoration’s authoritarian actions, therefore, radical right-wing ideas couldn’t gain political or popular traction at this point. While Heath experimented with Powellite laissez-faire economics – with letting it be – he abandoned the approach amidst rising unemployment and public resistance and returned to interventionist Fordism. Even Nixon asserted “we’re all Keynesians now,” and for all his right-wing rhetoric, largely pursued socially liberal policies. Moreover, while we often hear about the level of public support for Powell’s racist 1968 ‘Rivers of Blood’ speech, it’s less remarked that mixed-race Britons the Equals scored a huge hit with ‘Baby Come Back’ (1) the very same year, while their 1970 ‘Black Skin, Blue Eyed Boys’ (9) could confidently declare, “The world will be half-breed”.

For all the corporate consolidation occurring in this period, countercultural concepts still held sufficient sway to be co-opted rather than coldcocked, from 1969’s psychedelic bubblegum – Tommy Roe’s ‘Dizzy’ (1; US 1); the Archies’ ‘Sugar Sugar’ (1; US 1) – to Men’s Wear magazine’s “cool conservative” look,16 to Coke’s 1971 hilltop hippies’ television advert. This was the period of the corporations’ ‘house hippie’, and if the cynicism could be transparent – “If you won’t listen to your parents, the Man or the Establishment… why should you listen to us?”17 – the creative space this created for countercultural production benefited both musicians and fans. Despite the Bunkers and Garnetts, television was a progressive redoubt: with American networks ditching game shows, laugh-track comedy and small-town dramas, the trippy, multicultural Sesame Street (1969–) was emblematic of the era, while Britain’s Play for Today (1970–84) represented popular modernism at its most progressive. The ‘New Hollywood’ combined countercultural attitudes – Catch 22 (1970), Zabriskie Point (1970) – and psychedelic techniques – 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968). The film whose huge commercial success sparked this cinematic golden age, Easy Rider (1969), captured the period’s polarities: enduring countercultural utopianism violently countered by reactionary forces.

Just as the political settlement broke apart after 1968, so did popular music fragment and fracture. Nik Cohn calls this period’s music “a return to sanity, to responsibility”,18 but this is simply a pop variant on Suri’s claim that “citizens… longed to return to something they identified as ‘normal’ in a world undergoing dizzying change” – an acceptance of conservative concerns as consensus. Such critical bubblegum occludes the contestation that now defined pop and politics. David Crosby’s ‘Almost Cut My Hair’ - with CSNY - places his desire to let his “freak flag fly” in direct relation to state surveillance, as it “increases my paranoia” (Déjà Vu, 5; US 1). Mungo Jerry’s skiffly 1970 ‘In the Summertime’ (1; US 3) confronts this conflict amicably, assuring conservatives, “We’re no threat, people, we’re not dirty, we’re not mean”, voicing the solidaristic countercultural credo, “We love everybody”, while adding, defiantly, “but we do as we please”.

“Count Me Out/In”: The Counterculture, Radicalism and Revolution

The late 60s were the street fighting years, the period of Mao Tse Tung and Che Guevara posters on bedsit walls, the play-power of ‘radical chic’ and the firepower of the Black Panthers. Revolution was in the air and on the airwaves, but its meaning – and merit – were contested throughout the period’s popular music. The Beatles’ aggressive autumn 1968 ‘Revolution’ (B-side, ‘Hey Jude’, 1; US 1) responds to the new radicalism with liberal alarm – “when you talk about destruction/Don’t you know that you can count me out!” However, on the gentler version of the song on late-1968’s White Album (1; US 1), Lennon sings, “count me out… in”, with Ian MacDonald making much of recording dates proving that “out” postdates “in”.19 Yet in 1971 Lennon would release ‘Power to the People’ (7; US 11), dressed in full Maoist regalia,20 in which he revised his previous caution: “Say you want a revolution?/We better get on right away”.

The Airplane confronted this political polarity on the grandiose title track to 1968’s Crown of Creation (US 6): “In loyalty to their kind/They cannot tolerate our minds./In loyalty to our kind/We cannot tolerate their obstruction”, their communal singing strident but stunningly harmonised – the adversarial as universal love. By 1969’s Volunteers (US 13), they were declaring, “Gotta revolution/Got to revolution” on the title track, while ‘We Can Be Together’ deployed a Panther slogan – “Up against the wall motherfuckers” – as the Panthers’ Bobby Seale was gagged and chained to a chair in the concurrent Chicago Eight trial. The lyric is as close to Marxist analysis as popular music gets: “All your private property is/Target for your enemy/And your enemy is we”. The Doors’ summer 1968 ‘Five to One’ (Waiting for the Sun, 16; US 1) also articulates this face-off between counterculture and establishment, with Jim Morrison drawling with lascivious threat, “They got the guns/Well, but we got the numbers/Gonna win, yeah/We’re takin’ over”. Counting themselves out of this radical turn, Jethro Tull’s 1969 prog-pop delight ‘Living in the Past’ (3; US 11) tuts, “Now there’s revolution/But they don’t know what they’re fighting”.

The Rolling Stones managed to capture both this revolutionary conjuncture and the counter-revolution simultaneously. With its Indianate instrumentation, 1968’s ‘Street Fighting Man’ is a last gasp of psychedelic exotica amidst the authentocrat rootsiness of Beggars Banquet (3; US 5). The song’s assertion that “the time is right for palace revolution” is a counting-in that pulls against the Hobbesian pessimism of the album’s ‘Sympathy for the Devil’, where the darkness of ‘human nature’ – “‘Who killed the Kennedys?’… It was you and me” – is underlined by a frantic samba beat and banshee wails. Despite this lyrical conservatism, musically this was sheer radicalism, a swaggering demonstration of what the once-derided form of rock’n’roll could do. The apocalyptically haunting ‘Gimme Shelter’ on 1969’s Let It Bleed (1; US 3), therefore, draws energy from these contradictions. While again making no distinction between the violence of the state and its opponents, the track’s focus on the female principle, with backing-vocalist Merry Clayton taking the spotlight from 2:43, lends the song a visionary radicalism. With Clayton’s voice disappearing with the force of her screaming, “Rape, murder, it’s just a shot away” (2:57–3:01), Jagger emits a startled ‘Wooh!’ (at 3:02), at which point his final chorus switches to “Love, sister, it’s just a kiss away”, the countercultural feminine catalysing an assertion of Eros against Thanatos.

The conventional account of the Stones’ conservatism ignores the radicalism of their late-60s experimentalism, feminisation and queerness. While 1968’s ‘Jumpin’ Jack Flash’ (1; US 3) announces the authentocrat trajectory of their subsequent career, its promo clip, with the band in lipstick and eyeliner, queers their musical conservatism. While 1970’s Performance depicts Jagger’s polymorphously perverse rock star breaking down James Fox’s gangster machismo, 1971’s ‘Brown Sugar’ (2; US 1), for all its brilliance, marries musical to masculine authentocracy to become the ‘classic’ or ‘cock-rock’ paradigm, an equal opportunities chauvinism that parcels off countercultural queerness into glam’s uncocked rock. Nevertheless, that the queer Stones have no more place in gay history than in rock history is to the detriment of both. Amidst all this, New York’s 1969 Stonewall Riot launched gay liberation, a countercultural, adversarial, indeed revolutionary movement concerned with deconstructing the social codes of sexuality, gender and the family – with inauthenticity.

As Theodor Adorno argued, “Authenticity is supposed to calm the consciousness of weakness, but it also resembles it. By it the living subject is robbed of full definition”.21 This offers a way of reading this era’s ‘classic rock’ beyond its surface chauvinism. British heavy rockers Free are a case study in protesting too much: their stripped-down sound; the daft fighting talk of 1970’s ‘Mr Big’ (Fire and Water, 2; US 17); their absurdly priapic – and absurdly great – ‘All Right Now’ (2; US 4). Yet Andy Fraser, Free’s bassist and co-writer of both tracks, later came out as queer. Likewise, as the Kinks remodelled themselves as hard rockers for American arenas, they couldn’t resist queering their pitch as they entered the big tent, gloriously hymning the trans ‘Lola’ in 1970 (2; US 9). The song concludes with a gleeful deconstruction of gender – “Girls will be boys and boys will be girls/It’s a mixed-up, muddled-up, shook-up world” – that’s designed to mess with their new audience’s meat-head minds.

The Who’s undersold queerness indexes their political ambivalence. With the blues-rock bluster of 1969’s concept album Tommy (2; US 4) aimed at American audiences, the album’s depiction of child abuse still subverts the restoration family fetish, while the fact that Townshend voices all the female parts destabilises Daltrey’s audibly bare-chested machismo. Townshend counted himself out by hitting speechifying yippie Abbie Hoffman with his guitar at Woodstock, prior to performing Tommy’s (brilliant) song of distrust in mass movements, ‘We’re Not Gonna Take It’. Townshend then counted himself in by producing Thunderclap Newman’s insurrectionary ‘Something in the Air’, and out again on summer 1971’s superb but cynical Who’s Next (1; US 4). Decrying “the new revolution”, Daltrey howls, “Meet the new boss, same as the old boss”, on the churning, chest-beating ‘Won’t Get Fooled Again’ (9; US 15), prior to purchasing a mansion and a trout farm.

With Townshend deep in Eastern mysticism, Wolfe could wishfully declare, “In the long run, historians will regard the entire New Left experience as not so much a political as a religious episode wrapped in semi-military gear and guerrilla talk”. This conflates the late-60s revolutionary spirit with the spiritualism that co-opted its energies: what Gitlin calls the “transcendence industry”.22 With this materialist spiritualism sucking in several Fleetwood Mac members, the band’s extraordinary 1970 ‘The Green Manalishi’ (10) cleverly conflates ‘Mahirishi’ and ‘greenback’. The track’s huge sound, howling guitars and Peter Green’s ghostly vocal wails are poised in a liminal space between psychedelia and heavy rock: simultaneously vulnerable and aggressive, ‘Manalishi’ represents a tantalising road not travelled for 70s rock, with Green quitting the Mac soon after.

Wolfe’s ‘Me Generation’ polemic is as much of a mystification of the counterculture’s revolutionary impulses as the mysticism he derides. He has no explanation for phenomena like the epic title track of Traffic’s 1971 The Low Spark of High-Heeled Boys (US 7), which commends violence towards “the man in the suit [who] has just bought a new car/From the profit he’s made on your dreams”. With the imaginative potency of countercultural concepts meeting the material power of conservative reaction, it became imperative to take a side, “to speak out against the madness”, as David Crosby put it on spring 1969’s ‘Long Time Gone’ (Crosby, Stills & Nash, 25; US 6). Doing just that, Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young’s rapid-fire response to the Kent State killings, ‘Ohio’, in spring 1970 (US 14), was the countercultural elite being counted in, asserting the polarised political space between the reactionary state and a radical citizenry: “We’re finally on our own.”

We have made a playlist of all the songs discussed in this piece, from the sublime to the ridiculous. Enjoy.

This is a very lightly edited version of part of chapter four of Mixing Pop and Politics: A Marxist History of Popular Music, which is published by Repeater Books. New Socialist £5 and above subscribers can get 50% off Mixing Pop and Politics from Repeater Books.

-

The phrase “resources of hope” is the title of the 1989 Verso collection of Williams’ essays. Williams himself, as Robin Gable writes in his introduction to the volume, used the phrase “on a number of occasions”, the most notable of which is the title of the final chapter of Towards 2000, ‘Resources for a Journey of Hope’ (Chatto & Windus, 1983). ↩

-

Sheila Rowbotham. 2000. Promise of a Dream: Remembering the Sixties: London: Allen Lane, p. 196. ↩

-

Simon Reynolds and Joy Press. 1995. The Sex Revolts; Gender, Rebellion, and Rock’n’Roll. London: Serpent’s Tail, p. 167. ↩

-

Todd Gitlin. [1987] 1993. Years of Hope, Days of Rage. New York: Bantam, p. 420. ↩

-

From 1964-70, the number of Americans living below the poverty line dramatically dropped from 22.2 to 12.6%. ↩

-

Stuart Hall. 1968. ‘Hippies’, stenciled CCS pamphlet, p. 16. ↩

-

Jeremy Gilbert and Tim Lawrence. 2022. Love is the Message podcast, 20/09/2022, E11, ‘Huh! Here Comes the Funk’. Jordan Cummings points out the Grateful Dead regularly played benefits for the Panthers: ‘Forces of Chaos and Anarchy: Rock Music, the New Left and Social Movements, 1964 to 1972’, unpublished PhD thesis, p. 47. ↩

-

Quoted in Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor. 2016. From #BlackLivesMatter to Black Liberation. Chicago: Haymarket, p. 45. ↩

-

Joan Didion. [1979] 1993. The White Album. London: Flamingo, 1993, p. 19; p. 37. ↩

-

Simon Reynolds, 2005. Rip it Up and Start Again. London: Faber and Faber, p. 41. ↩

-

Michael Bracewell. 2002. The Nineties: When Surface Was Depth. London: Flamingo, p. 246. ↩

-

Tony Judt. 2011. Ill Fares the Land. London: Penguin, p. 94. ↩

-

Carl Freedman. 2010. The Age of Nixon. Alresford: Zero, p. 133. ↩

-

Jefferson Cowie. 2010. Stayin’ Alive: The 1970s and the Last Days of the Working Class. New York: New Press, p. 32. ↩

-

In terms of working-class cultural domination, see also Rod Stewart’s summer 1970 ‘Gasoline Alley’ (US 27) and the Hollies’ autumn 1970 ‘Gasoline Alley Bred’ (14). ↩

-

Thomas Frank. 1997. The Conquest of Cool. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, p. 192. ↩

-

Fred Goodman. 1997. The Mansion on the Hill: Dylan, Young, Geffen, Springsteen, and the Head-on Collision of Rock and Commerce. London: Jonathan Cape, pp. 78–9. ↩

-

Nik Cohn. [1969] 1996. Awopbopaloobopalopbamboom. London: Minerva, p. 227. ↩

-

Ian MacDonald. 1995. Revolution in the Head: The Beatles’ Records and the Sixties. London: Pimlico, p. 227. ↩

-

Bernie Sanders would deploy the song in his 2016 and 2020 presidential campaigns. ↩

-

Theodor Adorno. [1964] 2003. The Jargon of Authenticity. London and New York: Routledge, p. 100. ↩

-

Gitlin. Years of Hope, Days of Rage. p. 425; p. 424. ↩