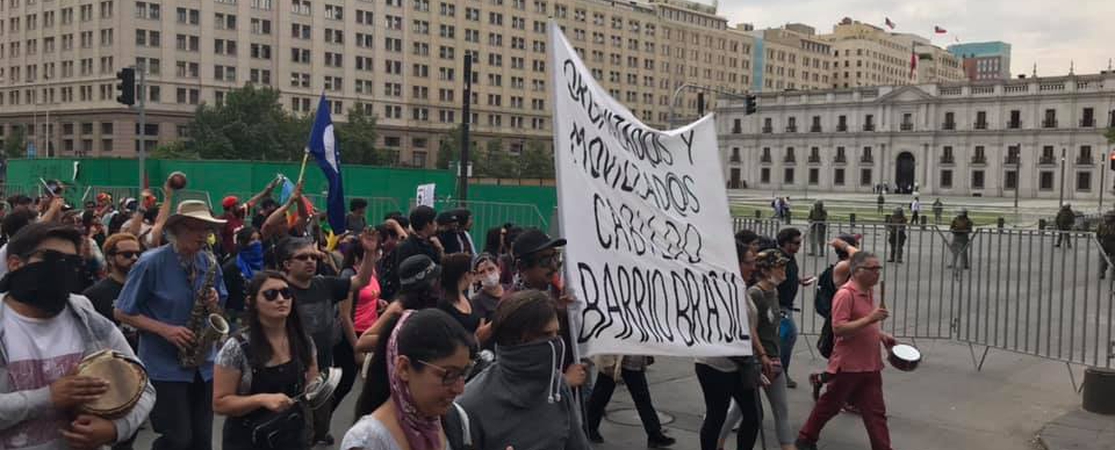

Thousands of neighbourhood assemblies have broken out across Chile, an account of how one functions in Barrio Brasil, Santiago, the development of capacities for self-management and its limits.

This article, an in-depth look at the Chilean uprising through the lens of a single neighbourhood, forms the second of a two part report. The first, a large-scale overview of the present rebellion, can be found here.

It’s 8:30 on a Monday night and a small group is gathering in the battered remnants of a 19th century mansion in Santiago’s part-alternative, part-proletarian Barrio Brasil. They’ve met here once a week for almost two months now, ever since October 24th. As Chile’s popular uprising has raged ever onward, thousands of such neighbourhood assemblies have broken out across the country - from the capital Santiago to Patagonia in the south and the Atacama Desert in the north. At least 15,000 people in a minimum of 142 areas have taken regular part.

Today’s meeting is a “zonal” one. Unable to organise in a detailed manner effectively on a barrio-wide scale due to the sheer size of the general assemblies, a decision was made early on to break the barrio down into four parts. Using the Plaza Brasil, at the neighbourhood’s heart, as their reference point, they stretch out to form a Northeast, Northwest, Southeast, and Southwest quadrant. Ours is the northwestern.

Like the totality of the barrio, our section is a mixture of newer high-rises and older once-mansions. Built in the 1880’s to house Santiago’s growing merchant class, the Barrio Brasil saw its economic fortunes start fall as the 20th century reached its median point. Unable to keep up with the costs of repair, the area’s new proletarian residents watched helplessly as these grand old homes fell into disrepair, a trend which continued until roughly the 1990’s. Around this time a young contingent of artistically inclined lefties joined the older residents, injecting the colour into the community for which it is now famous. Murals cover building after building.

Manuel, an experienced organiser with roots in the anti-dictatorship movement of the 1970’s and 80’s, informs us that Brasil has always had a leftist root. Communist Party posters remain a common sight at older cafes. However, as the area, like many inner urban neighbourhoods throughout the world, has moved towards a more transient population over the past two decades, some of this has faded. While sympathies certainly still lay with the left, many residents have found themselves disorganised. That is, until the recent outbreak of political upheaval.

Our northwest meeting tonight draws about ten people – small but not bad for ¼ of an area which measures under a mile in length by about a half mile wide in total. Overall the zone’s whatsapp group includes 80 individuals with attendance varying from week to week.

It’s a diverse group tonight, as most. A younger woman with short, dyed hair is the coordinator for this meeting (the coordinator roles are rotated every 2 weeks). Other than her there is a trade union militant, a couple of experienced neighbourhood organisers, a thirty-year-old with an interest in sociology, an older couple, and a few others, including a middle-aged woman entirely new to leftist organising. This is her first event other than a communal once (evening snack) earlier this week. Demographically, they include all the area’s constituencies – young, old, artistic, proletarian.

The discussion covers two primary topics. The first relates to the structural rules of the overall assembly. As the debate over April’s constitutional referendum grows along with the movement, more traditional political groupings are increasingly taking an interest in neighbourhood-level organising. Most notable among these has been Unidad Social (Social Unity), a broad coalition of leftist political organisations and trade unions. Many of these constituent groups, especially the unions, in turn have formal links with one of the three main left-wing parties or coalitions in Chile: the center-left New Majority (lead by the Socialist Party), the harder-left Broad Front, and the Communist Party.

Unidad Social has recently released a draft document detailing their demands for the structure in which the constitutional talks should take place, pushing local assemblies to endorse it. There is a feeling among some in Brasil that this goes against the explicitly pluralist, horizontal principles of the assembly. Perhaps more importantly, there is a perception that Unidad Social is uninterested in actually taking part in the organising work itself, interested instead primarily in using it to benefit one of their respective parties.

This is not a universal position, it should be noted. While the political class is highly unpopular, the exact nature of that unpopularity differs from party to party and from person to person. Manuel later points out to us the relative popularity of specific Communist Party office holders, particularly local ones with backgrounds in grassroots movements. However, this tension between base and center, the local and the national is an increasingly marked part of the movement as it closes in on its two month anniversary.

This anniversary is what the second half of our discussions entails. There is a widespread belief that now is a good time for reflection on what has worked and what has not. Members discuss how links with other areas have developed. They discuss each of the different ‘commissions,’ working-groups in our own parlance: Communications, Education, Environment, Culture, Health, Human Rights, and Abastecimientos (“provisions” roughly). They rate them on the Chilean 1-7 educational grading system. Most do very well.

It should be noted that there are also additional, autonomous groups, informally linked to the assembly which have grown up alongside but distinct from it. Particularly noteworthy among these is the Feminist Assembly. Formally launched as a woman and non-binary only space this week, its first meeting drew 14 people, again from diverse backgrounds both demographic and political, from those proclaiming that the “revolution will be feminist or won’t occur” to those admitting their “ignorance” about feminism altogether.

In these groups, particularly the commissions, we witness something of both the difficulty and beauty of a self-organised uprising. There are really three different overlapping but distinct strands to the Assembly’s work. The first is concerned with political organising. The goal here is to draw people in in order to subsequently mobilise them as part of the broader rebellion. The second is education – in which we would place the Feminist Assembly for example. The belief is that an understanding of society, its ills, and possible solutions is something of an end in and of itself, radicalising on a general level and thus creating the conditions for further action. Lastly there is autogestión, a popular term in Latin American leftist politics loosely translating to “self-management” but far wider in scope. Here the goal is to create the possibility of social reproduction on a communal, egalitarian basis. In this sense, it takes a more ‘concrete’ approach than the purely educational portion, focusing on generating alternative, horizontally structured, local institutions focused on meeting material needs.

Two examples to illustrate this last goal as it is in some ways the most immediately ambitious. The first is a recent ‘day of health.’ Alongside the weekly Saturday assemblies in the late afternoon, each weekend features a series of workshops on a specific theme. Last weekend’s was health, with a focus on giving community members the specific skills necessary to help identify and treat common illnesses (primary healthcare in Chile is often very expensive) as well as tear-gas related symptoms (a common problem at the demonstrations). Free HIV testing was also offered along with a number of other workshops.

In addition, there was a fundraiser. The goal was to help raise money for a new, free-at-the-point-of-access, self-organised, community pharmacy. According to rumour, it is going to take physical form in the husk of the old commercial pharmacy near the Plaza Brasil – this, like many such pharmacies, was smashed and looted during the initial uprising and has since been abandoned.

There is also a growing consumer cooperative attempting to self-organise the world of food. Having made direct links with small farmers in the countryside, it allows neighbourhood residents to collectively purchase whatever they need directly from the producer at a fraction of the prices found at supermarkets. Where possible, they buy organic, free-range and with a low carbon footprint. This is rapidly proving one of the assembly’s most popular initiatives, the first food distribution including over eighty household.

What do you want to see in the future?

“What do you want to see in the future? In the short term, medium term, and the long term?” asks our coordinator. A balding old militant wearing a loose-fitting white cotton shirt raises his hand. “In the short-term, I’d like to see us build more links with other assemblies in other territories,” he says. “In the medium-term, for these links to develop on a national basis. In the long-term, to seize power.”

The room applauds. However, in a way our comrade’s statement perfectly depicts both the grand potentials and real difficulties for this revolution. The spirit of the movement thus far has been largely anarchic – from the rioting and looting to the autonomous neighbourhood assemblies.

While it has been compared both internally and internationally to the Arab Spring or the uprising in the Ukraine, I would disagree with this characterisation. The Arab Spring was fought largely over democratic rights. In Chile, while democratisation and human rights are important threads of the argument, material demands remain central. This is not to say, as I argued in my initial piece, that these demands are economistic and they are far from narrow. Rather, they take as central the inequalities of power and life chances generated by a neo-liberal capitalist system, including these inequities’ social manifestations. Calls for “dignity” have been widespread, as have attacks on “social segregation” and classed exploitation. Moreover, their expression has been social and small-p political, often articulating themselves in opposition to the neoliberal state system introduced at the end of the Pinochet regime. In this they retain a deeply revolutionary underpinning and differ significantly both from more liberal abstractions oriented purely towards formal, democratic rights and economistic ‘solutions’ such as an increase in pensions, a freeze in the metro fare, or the raising of the minimum wage.

Instead, it may be more useful to look towards the civil strife in Argentina during 2001 and the preceding years. The context was different of course. Argentina was then in the midst of a terrible economic depression that had seen 28% of the country’s GDP wiped out. However, in its highly-politicised, de-centralised, horizontal nature, along with the central agitational role played by inequality, there are certainly similarities.

Most importantly, as in Chile now, Argentinians looked towards localised, small-scale autogestión as a simultaneously prefigurative and immediately practical alternative to capitalism. While in Argentina this most famously took the form of factory occupations rather than neighbourhood assemblies, the core principal remains the same. In fact, Chile has also seen a number of school and workplace assemblies – the only secondary school in our area is currently occupied. However, while toppling three presidents, the Argentinian movement was unable to ultimately displace the state. Instead, as Juan Carlos Monedero points out in an article in the most recent New Left Review, this revolutionary movement ended up incorporated into the traditional form of Peronism.

This diffusion of popular power into political parties embedded in clientalist models ultimately diffused the movement in Argentina. Revolutionary self-management was replaced by sectoral welfarism. Of course, the socio-historical situation in Chile is very different. Notably, it lacks the Peronist populist tradition. The Socialist Party is certainly unlikely to gain much of a benefit from the uprising here. Nor is the Broad Front after their endorsement of the government’s repressive agenda. The Communist Party may rise slightly in popularity, but it seems unlikely that another Communist Party will ever seize power anywhere in Latin America.

That said, the question of transition remains. Neighbourhood assemblies have increasingly joined their cousins in Plaza de la Dignidad in actively displacing the capitalist state, both physically and structurally. The opening of a community pharmacy will be a major victory, just as the food-cooperative has been. At the same time, the process of political debate and education both radicalises individuals and gives them faith in their ability to govern outside of capitalism.

However, the question, as we discussed at the meeting and again with Manuel in a communist cafe just off the plaza, is how to move from dissent, from riots, from neighbourhood assemblies, from free pharmacies funded, effectively, by localised, decentralised charity, into an actual revolutionary moment. 29% of Chile has protested, however that has not been enough. Following clashes on the International Day of Human Rights on Tuesday, two more protesters are in critical condition. Still, the government does not budge.

Much more remains to be written on the neighbourhood assembly model. Much more, in fact, remains to be discovered through its actual practice. The success of the food cooperative and the potential for a pharmacy is likely to spur forward additional initiatives. These cooperatives, however, cannot displace the state or capital alone. If anything, they are most important as they maintain us and educate us in radical self-organisation. However, a decisive moment is needed. When, if, and how it will come remains to be seen.

In the meantime, here in Barrio Brasil, the struggle continues.