Not even the most optimistic Irish Marxist could have predicted that they would be seeing Che stare out from the top corner of an envelope, his face on a newly minted government stamp.

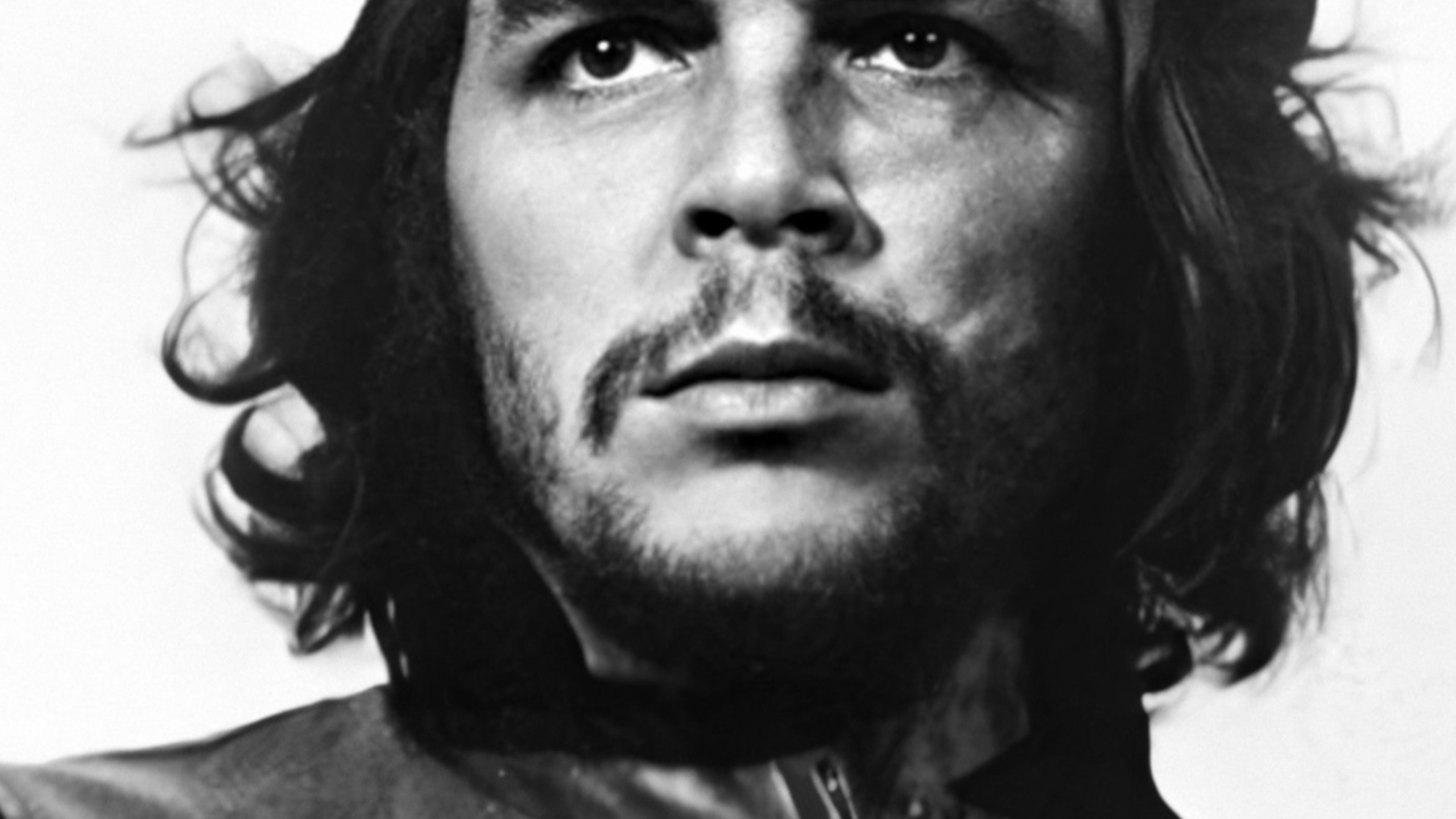

The black beady eyes looking over your left shoulder as you face into them, the black beret effortlessly lounging on the top of his head, the left cheek dimming into the shadow of his long black hair; we all know it, it is the icon’s icon. Jim Fitzpatrick’s stylised drawing of Che Guevara is ubiquitous, an emblem of leftism that adorns everything from posters on college apartment walls, to Diego Maradona’s arm, to a t-shirt worn by Lindsay Lohan in Confessions of a Teenage Drama Queen. It is, to quote The Sunday Times – hardly a bastion of pro-Marxist sentiment – an “image [that] has continued to hold the imagination of generation after generation”, but not even the most optimistic Irish Marxist could have predicted that they would be seeing Che stare over their shoulder from the top corner of an envelope, his face on a newly minted government stamp to mark the fiftieth anniversary of his death.

It is too late to preface the Irish right-wing’s collective meltdown amidst gurgles of “murderer” and the like, but it must be said that it makes perfect sense for Ireland, under any government, to honour Che Guevara. The Cuban struggle that birthed the legend of Che is a near-mirror image of the Irish struggle for independence; both were small island nations dictated by the whims of imperial neighbours that fought for independence through guerrilla warfare. While the original portrait photo of Che was done by the photographer Alberto Korda in Havana at a memorial service for the victims of the La Coubre explosion, it is the famous stylised adaptation done by the Irish artist Jim Fitzpatrick in 1968, in response to Guevara’s death in ’67, that takes its place on the stamp. Then, there is the oft-cited Irish ancestor in Guevara’s bloodline.

Ireland’s relationship with Che

Guevara’s father once said that “the first thing to note is that in my son’s veins flowed the blood of Irish rebels,” and this quote is often recycled among the Irish left, but few realise how accurate it is; Che was the great-great-great-great grandson of Patrick Lynch, who followed a family trend of immigration that began when his family lost important battles: first against the forces of Oliver Cromwell, and then against those of William of Orange. To call the Lynch blood the “blood of Irish rebels” seems somehow disingenuous; yes, they fought to repel foreign invaders, but they did so and had the means to do so because they were one of Galway’s fourteen ruling tribes who dominated western Ireland’s biggest city from the 13th to the 19th century. Lynch’s childhood in Lydican Castle, and the fact that his mother was a Blake – another of the fourteen tribes – meant that his upbringing was far removed from Che’s, whose parents, despite claims from others of aristocratic living, had neither power nor money according to his brother Juan Martín. The fight of the rebels in his bloodline was not Che’s; they fought to maintain localised feudalism, he fought so that the people would be, as he said, masters of their own destiny.

One of the most recognisable aspects of Irish identity is our desperation to acknowledge and honour members of the diaspora, no matter how distant. Add in the fact that the country is sworn to neutrality in matters of international relations, it makes sense that governments and people would do so across the political divide. We do it for Kennedy, we do it for Reagan, we even sent official condolences to Germany upon the death of Hitler; of course we can honour Che Guevara.

The stamp’s first printing run sold out within a week and it was always going to. He may be fifty years dead, but Che Guevara still inspires in a way that few figures, dead or alive, can. His appeal was summarised in the title of the original photograph: Guerrillero Heroico. His all-too-brutal death, executed by the Bolivian Army and the CIA without due process, his corpse photographed and displayed like a stuck pig – or Mantegna’s Christ, if you’re John Berger – only solidified his legend. He was a guerrillero who died heroically, fighting for the freedom of Bolivia, after a similar, but ultimately unsuccessful attempt in Congo. A myth while he still lived, a romantic martyr-in-training who predicted his own death, Guevara was someone who, as Berger put it, “recognised what was intolerable for man and acted accordingly.”

That members of the broader mainstream left in Ireland, from Sinn Féin leader Gerry Adams to socialist Teachta Dála (member of parliament) Paul Murphy, would treat this a boon is no surprise; just as it is no surprise to see people such as Senator Neale Richmond apoplectic on national news. Yet Richmond is a high-ranking member and spokesman for EU affairs of the ruling party, Fine Gael, the very same party who would have had to sign off on An Post, the publicly owned postal service, releasing the stamp. Jim Fitzpatrick himself said that it was “spectacularly interesting” that the centre-right Fine Gael, opposite in every way to the Marxism-Leninism that Guevara died fighting for, would choose to honour the revolutionary.

Countercultural Commodification

The adaptation of countercultural and radical figures and movements is of course nothing new for regular capitalist business and companies. Fitzpatrick’s image is one of the most appropriated of all time - due in part to the artist’s refusal to copyright it until 2011, repulsed by the “crass commercial” use it had been subjected to - but to see a government doing it seems all the more cynical. Fine Gael have form for this kind of thing; see last year’s centenary celebrations of the Easter Rising, when stamps bearing the face of the Scots-Irish Marxist James Connolly were sold alongside the likenesses of his fellow signatories of Poblacht na hÉireann – the declaration of the Irish republic.

To commodify something for the purpose of selling it is to claim ownership of it, and centre-right governments commodifying the iconography of the left is their attempt to adopt a revolutionary and idealistic image without adopting the politics. They know that it is only through what Ben Ehrenreich called “the shedding of Che’s radicalism and ideological rigour”that it becomes possible to market him on a government product. It is a more subtle move, but still along the lines of Hillary Clinton’s recent comments about the world being at its best when it functions between centre-left and centre-right, ergo in the direct centre, where ideology dies. Fine Gael’s stamps are telling us that Connolly and Guevara may have been onto something, but they just needed a 12.5% corporation tax to really steady the ship. The stamps scream at us that we are still in Fukuyama’s End of History and Fisher’s Capitalist Realism simultaneously. “Ideology is dead” is screamed from the top corner of your envelope; we are all one glob of a market base now.

As Clinton’s quotes show, this is not a strictly Irish phenomenon; lately we have had Theresa May’s galling attempt to depoliticise Frida Kahlo by wearing a bracelet featuring the Mexican Marxist’s face, and earlier this year we had Emmanuel Macron singing the praises of the French Republic, all the while mourning the death of the King.

Nobody will begrudge Jim Fitzpatrick for profiting from the use of his image. Artists, like all of us, must survive under capitalism, and their lives are often precarious at best, especially under Fine Gael. Fitzpatrick has made the picture available for free download, for personal use, and his resolve seems pure, as does the joy with which leftists have celebrated the success of the stamp. Fitzpatrick’s eloquent defence of Guevara against what he called “black propaganda” on the same broadcast that featured Neale Richmond calling Che a “barbaric murderer” was an extraordinary and refreshing sight to see broadcast by RTÉ, Ireland’s state broadcaster.

It makes perfect thematic sense that the stamp would be released in the same week that Fine Gael outlined their budget for 2018. We only saw Che in government through television screens, and Connolly was executed before he ever got the chance, but we can say with the utmost certainty that neither would have tackled a housing crisis with a measly thirty-one new public housing units, nor would they have planned to ban public worker strikes. The stamps, May’s bracelet and Macron’s imaginary republic longing for a King all expose the contradictory and hollow nature of centre-right government; they can sell you the pictures, but they would never give you the people depicted.