The support of most Labour leadership candidates for trans rights is welcome. But arguments over 'sex' and 'gender' miss the sheer complexity and bureaucracy of current laws on gender recognition.

This piece was originally commissioned for another British left publication. The finished piece was accepted before being cancelled at the last minute, without a clear explanation. The British left has been notable for its resistance to the politics of trans liberation. Anti-trans voices are prone to declaring themselves ‘silenced’, so it is my hope to give their claims the scrutiny they deserve here.

In light of recent controversies around gender, each of the Labour Party leadership candidates have been quizzed on their position concerning trans rights. While fielding a Q&A on well known transphobia hub Mumsnet, frontrunner Keir Starmer affirmed that “trans rights are human rights”, stressed the need to update the Gender Recognition Act, and made qualified calls for a “respectful dialogue” (certainly an optimistic hope). After qualifying that she “understood arguments on all sides of the debate”, left-wing candidate Rebecca Long-Bailey recently affirmed to the BBC’s Laura Kuenssberg her support for self-identification as the legal basis for gender transition. She also expressed empathy that the existing process of gender transition was “very, very difficult”. Candidate for Deputy Leader Dawn Butler has argued that trans women should under no circumstances be jailed in male prisons. Even the shortlived leadership campaign of Jess Phillips featured a sympathetic interview between the candidate and a trans journalist. The much-criticised Labour politician remarked: “no trans person I have ever met said that they didn’t want me to use the term ‘breastfeeding’, or to talk about my periods.”

In other words, for the most part Labour leader contenders are largely in agreement over supporting reforms to improve the lives of British trans people. Only the hapless Clive Lewis sounded a more sceptical note. Lewis responded brusquely to an email from a constituent that the topic did not seem relevant in Norwich (in fact home to both a wide selection of trans-support groups, and one of the country’s highest profile transphobes). Lewis also enclosed a rambling correspondence from an unnamed ‘friend’, effectively farming out his ‘PC gone mad’ bigotry to an unspecified third party. Thankfully, the Shadow Minister for Sustainable Economics dropped out of the race shortly after.

At the time of writing, all the contenders for Leader and Deputy Leader besides Keir Starmer and Richard Burgon have signed the pledges proposed by the Labour Campaign for Trans Rights (although Lisa Nandy has since said that its call for the expulsion of transphobes ‘gave her pause’).

The most controversial positioning during the leadership race has come not from a contender, but from former Prime Minister Tony Blair. Blair predictably opined that the topic was a sideshow compared to issues such as ‘immigration control’ (which, presumably, he still believes should be a key priority for the Party). On the left of the party, a wideranging ‘letter to the movement’ from the recently unseated Laura Pidcock included (nestled, bizarrely, between comments on Palestine and nuclear weaponry), the following line: ‘The women’s movement needs the space to talk about sex and gender, without fear of being ‘no platformed’. We reserve that measure for fascists.’ This remark was widely interpreted as a dogwhistle, signalling her scepticism concerning the struggle for trans rights. Tellingly, right-wing weekly rag The Spectator was quick to move in socialist Pidcock’s defence. But why did this seemingly innocuous point cause such a stir?

At first glance, the Labour Party’s 2019 manifesto appeared to be unflinching in its support for trans people, writing that it not only supported the controversial reforms to the Gender Recognition Act (2004), but saw these as insufficient:

Labour is committed to reforming the Gender Recognition Act 2004 to introduce self-declaration for transgender people, but we are not complacent about the culture shift required to make LGBT+ inclusivity a reality. (p.68-69)

But a few pages earlier, there was a proposal which raised alarm amongst trans activists. On page 66, in a section headed Women, Labour assured the electorate they would:

Ensure that the single-sex-based exemptions contained in the Equality Act 2010 are understood and fully enforced in service provision.

Certainly, fostering a clear understanding of relevant legislation around protected characteristics is a valid concern for the Labour Party. But understanding the current meaning of the ‘sex’ as a legal term has become more difficult than ever, as the Equality Act has received intense scrutiny on these grounds.

The Equality Act’s sex-specific exemption provisions were originally best known for formally enshrining the continued legality of gentlemen’s clubs. In an unlikely twist, they have now come to be focused on very closely, owing to one of the nastier episodes in the history of the womens’ movement. Originally intended to protect the interests of Peter Stringfellow and the gents of St. James’s, today sex-specific exemptions have been mobilised in insurgent efforts by those minded to push trans people out of public life. In recent years, transgender people have come under continual criticism by a vocal minority tendency of the feminist movement. Self-described ‘gender critical’ feminists are in many cases concerned with vanishingly few other issues. Their social media feeds brim with commentary on the latest developments in what they call ‘trans ideology’, and their public events focus on very little else.

This tendency appears to be peculiarly localised within the UK, contrasting with feminist movements elsewhere across Europe and North America (including Ireland). Transphobic feminists are notable for framing themselves as constantly being ‘silenced’ by the establishment, despite having unparalleled access to both opinion and news reporting pieces in papers such as the Guardian, Times, New Statesman, Spectator, and Daily Telegraph, as well as the Scottish paper the National and television programmes such as Newsnight. This distinctively British flavour of transphobic feminist generally argues that sex is an immutable and fixed characteristic, identifiable at birth. (Intersex people are, confusingly, declared to be ‘really’ male or female, with transphobic feminists here echoing earlier medical terms such as ‘pseudo-hermaphrodite’). From this view, trans people’s gender identity appears as an irrelevance next to the letter of the Equality Act. While genders may change with history, the argument goes, sex is a natural fact and beyond discussion.

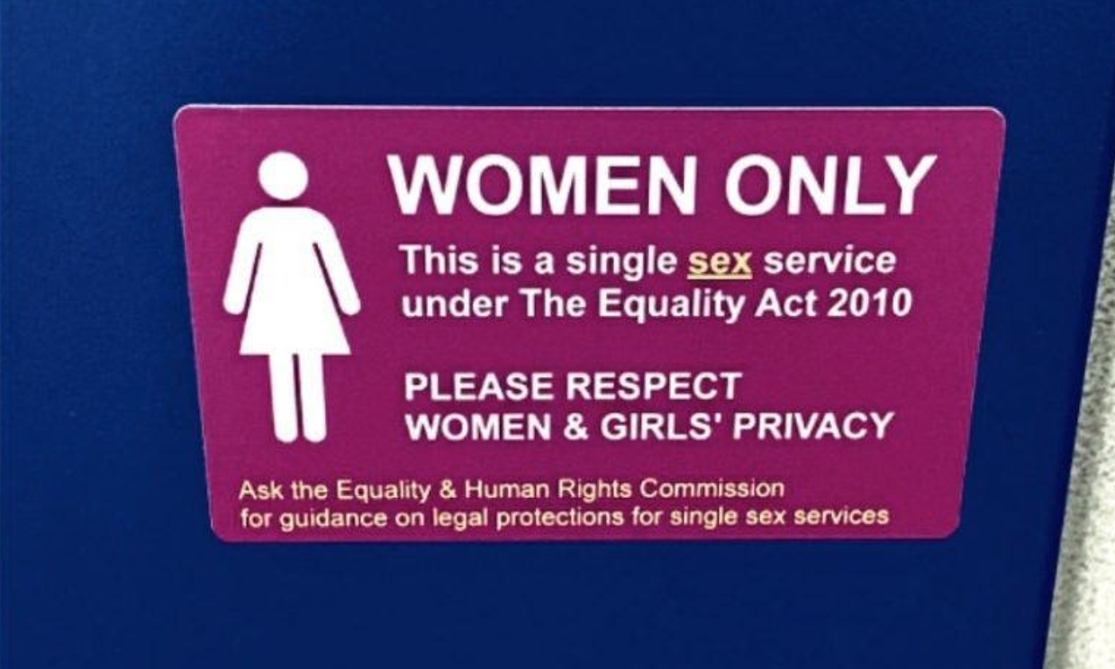

This attempt to distinguish between sex and gender is exemplified in these stickers, which transphobic activists have distributed in public toilets and train facilities:

A sticker reading “WOMEN ONLY. This is a single sex service under The Equality Act 2010.”

A sticker reading “WOMEN ONLY. This is a single sex service under The Equality Act 2010.”By this reading, to be a ‘human adult female’ can only mean to be cisgender. Unfortunately for this interpretation, a tidy division between sex and gender is rarely (if ever) to be found in English or Scottish common law.

For instance, at birth infants are legally required to be registered by their parents as either male or female. In England, this is required within 42 days of birth, and in Scotland within just 21 days. This timeframe offers no scope for children themselves to be involved in the assignment of their sex. This requirement is most concerning for parents with intersex infants, who are often born with ambiguous genitals. The British intersex activists I spoke with while researching this aspect of the Gender Recognition Act reforms told me that this legal requirement was often used by doctors as one pretext to push for cosmetic surgeries on intersex children. This legal requirement has no exemptions, and relatively high stakes: in the case of parents proving to be mistaken, there is no clear means of a reversal. While reportedly issuing a ‘correction’ for intersex infants and children has been possible on an ad hoc basis, there appears to be no established formal procedure. Once a child’s sex is marked, their future is set in various ways. For example, attending a boys’ or girls’ school is only legally permitted for those with a matching male/female birth certificate (that is, for these institutions, sex and gender are for all practical purposes interchangeable.)

As can be seen from these examples, the British state as it currently operates is quite demanding: it insists upon registering the sex of infants, without regard for whether this is reliably possible in the earliest months of life (if at all). In this way, ‘sex’ as a legal category is not just a run-of-the-mill fact, but also a matter on which parents are tacitly coerced into picking from one of two options. The state makes our sex its business from birth.

As is well known, by later on in childhood and throughout our lives, many are left unhappy with our officially designated sex. How to rectify this situation is a complicated question. Changing one’s formal sex marker is possible for transgender and intersex people through various channels, each with their own mandates and procedures. For the sake of simplicity I will leave out the National Health Service, which provides sex-affirming medications for those experiencing gender dysphoria, and focus on the question of more basic sex registration.

Updating the sex found on one’s passport is a pressing concern for British trans people living, working, or even just holidaying abroad. Even travelling safely through states with hostile policing attitudes towards trans people is not assured to those with apparently incongruous documents. These concerns usually become increasingly pressing for those trans people who’ve opted for Hormone Replacement Therapy. There are also several intersex variations which only make themselves fully apparent at puberty, or after treatments we deem unnecessary are discontinued. Changing the sex marked on a British passport requires documentation from one’s employer or local government, an assessment by a psychological professional (written or officially translated into English) affirming that the change is likely to be permanent, a deed poll indicating a change of name, and proof of that name being in current use. Those wishing to transition while living abroad are effectively left in a bureaucratic catch-22: without an accepting workplace, they are often unable to update their local government registrations, for lack of the relevant passport.

Notably the passport uses only the terms male or female (M or F on the document itself); the gender-specific terms man or woman do not appear. As with the division of boys’/girls’ schools, the division of sex and gender does not arise in terms of access to any relevant organisations. Despite a recent legal challenge by a non-binary activist, no option for marking one’s passport sex as an X rather than an M or F is currently provided by the British state. (Eight countries previously colonised by Britain offer these markers: Australia, Malta, New Zealand, Pakistan, India, Ireland, Canada and Nepal, as well as Denmark and Germany). The more elaborate process of pursuing a Gender Recognition Certificate allows trans people to achieve a thoroughgoing re-registration of their sex with the state. (It’s also possible to reissue one’s own birth certificate, with a corrected sex marker). A process usually requiring hiring a lawyer, and overseen by a deliberating body of purported experts (almost exclusively cisgender), acquiring a GRC is a uniquely daunting bureaucratic feat.

As Elaine O’Neill wrote last year in her assessment of the Labour Party’s manifesto stance on trans rights, the 2004 Gender Recognition Act was credited with:

finally giving a legal pathway for gender recognition, albeit in a draconian and unworkable fashion involving a shadowy Gender Recognition Panel, none of whom you got to meet, deciding whether you should be allowed to have your gender legally changed, and even then only with a large bundle of evidence, whereby you effectively had to fit into the traditional transitioning transsexual box to have a chance.

Once completed, a Gender Recognition Certificate shifts one’s formal registration from female to male, or visa versa. At present, it does not allow for non-binary identification. This also means that people with intersex variations who would like to avoid ‘M’ or ‘F’ markers altogether are unable to do so.

Once again: despite its name, the Gender Recognition Certificate does not only alter one’s gender as registered with the state. Far from accepting trans women as ‘male women’ and trans men as ‘female men’, the Gender Recognition Act (2004) is unambiguously clear on these terms being merged for all practical purposes, in the eyes of the law:

Where a full gender recognition certificate is issued to a person, the person’s gender becomes for all purposes the acquired gender (so that, if the acquired gender is the male gender, the person’s sex becomes that of a man and, if it is the female gender, the person’s sex becomes that of a woman)

The Gender Recognition Certificate (GRC) has occupied a strange place in recent years: the process is a complex, convoluted and extended one—so much so that, in light of the mooted reforms to the Gender Recognition Act, some administrators were until recently advising trans people not to bother. Now, however, Gender Recognition Certificates serve as a flashpoint for one of the most ferocious in-fights in recent feminist movement history, and seem set to remain a feature of transgender life into the foreseeable future. They also retain prominence in more recent legal rulings.

In a recent ruling against charity worker Maya Forstater’s unfair dismissal appeal, Forstater’s stated determination to disregard self-identified gender was declared to be beyond the limits of what is acceptable to civil society. Key to this ruling was Forstater’s refusal to use even legally identified genders of trans (or intersex) people. This is a stance that seems to extend well beyond opposing self-identification. In published deliberations, the presiding judge noted the following:

If a person has a Gender Recognition Certificate this would not alter [Forstater’s] position. The Claimant made it clear that her view is that the words man and woman describe a person’s sex and are immutable.

This perspective is then contrasted to both expert testimonies on intersex variations (it remains unclear what Forstarter would call us), and to relevant legislation. Clearly, the official protection offered by the GRC’s reassignment of sex remains of great importance in legal terms, and trans people can be assured at least this degree of relief concerning our ‘protected characteristic’.

This lack of legal distinction between sex and gender is not a fixed matter. It’s easily possible to imagine legal reforms that would introduce a conceptual split of the kind pushed by transphobic feminists. This could be easily introduced through new legislation, or through precedent-setting rulings. As it stands, however, the British state has made formal transition an arduous process for trans people, and insists upon assigning infants a sex in a fashion which does not always prove practically possible. But once undertaken successfully, gender transitions formally re-register one’s sex, and afford transgender people accompanying protections.

Many of the difficulties concerning transgender issues originate in the unhelpful complexity of this system, which straddles various different parts of the government (from Her Majesty’s Passport Office in Liverpool, to the dedicated committees who oversee GRCs, to the NHS Gender Identity Clinics). But transphobic feminists are attempting, in bad faith, to introduce a new dimension of confusion to these discussions. The law as it stands is a mess, but is ultimately quite clear on questions of sex. Contrasting with the likes of Forstater, the British legal system accepts that sex is mutable, albeit while insisting that any changes must be difficult to effect, and binary in nature.

It’s encouraging that the Labour leadership campaign’s frontrunners share a commitment to formally supporting trans rights, although they seem more divided on the question of how, if at all, to address the problem of transphobia within the Labour Party. Any reforms towards state registration of gender should include not only a shift towards self-identification, but also a correction of the current problems of intersex registration and the pervasive non-recognition of non-binary people. As the Labour Party’s 2019 manifesto acknowledged, no single piece of legislation will provide for the liberation of transgender and intersex people. Trans people face down commonplace indignities—from street harassment to shoddy healthcare to interpersonal abuse to the continual drumbeat of the on-going media moral panic, all of which seem likely to resist the obvious legislative fixes. But neither can we entertain a ‘debate’ which, through conceptual sleight of hand, erodes the piecemeal improvements achived through a ten year old law. Across the early 21st century, important breakthroughs were made, even if these victories are much more limited for intersex and non-binary people. Trans men are males, trans women are females, and for all its failings, the law has already come to reflect this.

‘Transgender Marxism’, an anthology of new essays on transgender experiences and class politics edited by Jules Joanne Gleeson and Elle O’Rourke, can be pre-ordered here.