Universal basic services will not address all the flaws of universal basic income. It's the bare minimum, and we should aim higher.

Over the last few years, excitement about the idea of ‘universal basic income’ (UBI) has reached a fever pitch. UBI – an unconditional payment from the state to all or the majority of a country’s citizens – is touted as the solution to all of modern capitalism’s problems. With the prospect of mass unemployment resulting from rapid improvements in labour-saving and labour-replacing technologies on the horizon, a universal payment of some kind has been proposed by everyone from libertarians to communists, and many in between. UBI has become that rare cross-ideological idea, capturing the imagination of those on the right who acknowledge the economic challenges ahead as well as those on the left who support a fairer distribution of income.

Predictably, the response from some quarters has been to praise the idea but lament that it is unaffordable and therefore unworkable. Some recent analysis of the likely cost of even a minimal UBI in modern Britain has found that it would cost almost £150bn extra per year. Even the complete dismantling of the welfare state, which some libertarians would argue for, would not be enough to pay for a full UBI.

In response to this issue, a number of other proposals have been put forward. Negative taxation would involve a similar principle, but the payment would be part of the income tax system, with the result that only those below a certain income threshold would receive any money. Others have argued that the current system of Universal Credit — broken and poverty-inducing as it is — represents an opportunity to provide genuinely universal and non-means-tested benefits to a significant portion of the population.

Another proposed alternative to UBI comes from the UCL Institute for Global Prosperity, which recently released a report outlining a fiscally-neutral proposal for ‘Universal Basic Services’ (UBS). This would involve the extension of the ‘NHS principle’ to cover housing, food, transport, and IT to counter the threat posed by automation. UCL argues that this would ‘raise the floor’ of basic services all citizens can expect and ensure that these services are free at the point of use. The proposal is framed as an ‘affordable alternative’ to UBI.

Transformative or affirmative?

Many on the left are sceptical about UBI. This is not because they don’t believe people should be paid enough to survive regardless of whether they can find productive employment. The main criticism of UBI from the left is that it would not be as transformative as some proselytisers suggest: although UBI tackles the consumption side, key questions around ownership of the means of production are left unaddressed. Whether or not it’s ‘affordable’ should be a secondary consideration; without fundamental structural reforms to our economic system, UBI will only be a sticking plaster papering over the cracks.

Many of the left’s challenges to UBI can also be applied to UBS. The primary advantage of UBS over UBI is its push for decommodification: by providing high-quality public services that are free at the point of use, UBS would shelter citizens from the vagaries of the market whereas UBI would leave them more exposed. On the other hand, that’s hardly enough. It’s hard to argue against the aim of universal basic services – clearly, public services that allow people to survive with a certain level of dignity are a good thing – but the first thing that comes to mind when you read the report is, ‘Shouldn’t we be doing this anyway?’

The ‘affordability’ trap

What’s more, because they attempt to solve the red herring of ‘affordability’, the proposals for UBS turn out to be quite objectionable. Taking a closer look at the details reveals that these services are far from universal. To benefit from the maximum value of the scheme, a household would need to qualify for the housing element, and only 1.5 million households would be eligible. For the vast majority of other recipients, the RSA finds that the proposals would provide a mere £39 per week of extra value. For those who don’t live in a city, and therefore don’t stand to benefit from the transport investments, this falls to just £18 per week.

These meagre proposals undoubtedly result from the warped insistence on ‘fiscal neutrality’. The idea that current levels of public spending are desirable, after a decade of some of the deepest cuts ever witnessed in a modern state, is ludicrous. We should not shy away from increasing public spending to finance an initiative that is both an investment in human capital and a massive macroeconomic intervention that would boost private spending power. What’s more, the concept of ‘affordability’ is very elastic for an established sovereign state in control of its own monetary policy.

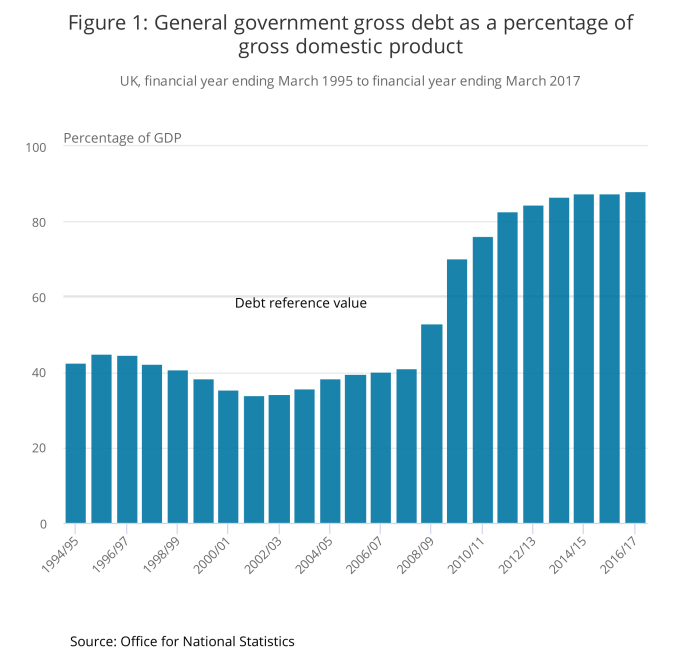

Emphasising fiscal neutrality plays into the hands of those who insisted on implementing austerity in the first place. Austerity was never about ‘paying down the public debt’. This debt resulted from the decision to bail out the banks after the financial crisis, not the profligacy of an overly generous democratic state. And in any case, it is impossible to reduce levels of public debt through spending cuts without substantial investments in the long-term productive potential of the economy. This is why, ten years after the crash, the UK’s public debt is still rising.

Have we really given over so much intellectual ground to the last decade’s failed austerity narrative that we now need to put forward a rebranded argument for basic, life-sustaining, worker-supporting public services?

Were it not for the ideological retrenchment that has taken place over the last thirty years, any sensible economist or politician would have argued that basic provisions for health, housing, food, and transport were not only moral imperatives, but economic necessities in a society that relies on human capital as its primary factor of production. People who can’t eat, or sleep, or access healthcare can’t work in the places that neoliberals suggest create so much of our economic value.

And this is what we are starting to see after a decade of austerity. Employment is the highest it has ever been, but wages have stagnated, and private debt levels are approaching pre-crisis levels. As a result, child poverty is at its highest level since 2010 and one in every 200 people in the UK is now homeless. Moreover, the basic goods and services we would require to alleviate these problems – from our NHS, to children’s services, to social housing – have been eviscerated. What we are left with is not only a broken society, but a broken economy too.

Beyond UBS

Clearly, growing our economy will require massive increases in investment in our public services. But any worthwhile implementation would have to be more substantial than what was proposed in UCL’s report. The provision of public services is a basic requirement for any modern economy. Rebranding these fundamental services as a gimmicky ‘nice to have’ like UBS risks ceding more ground to those who eviscerated our public services in the first place.

What we need now is not a technocratic, fiscally neutral argument for ‘universal basic services’. Instead, we need to expose the moral and logical vacuum at the heart of the austerity narrative, and tackle the underlying issues that have created such huge disparities of wealth in the first place. To truly make the UK’s economy fit for the 21st century, wealth must be socialised, models of ownership radically rethought, and power redistributed away from capital and towards labour.