Prior to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the obituaries for Boris Johnson’s premiership were already being written. An increasingly confident Labour opposition had a striking lead in the polls. Johnson’s ‘interventionist’ brand of populism seemed to be failing to tackle a cost of living crisis brought on by post-pandemic supply shocks and a dramatic hike in energy prices. This in combination with the series of ‘partygate’ scandals looked like it might not only bring down Johnson, but tarnish the reputation of the entire Conservative Party. Yet, within a few short weeks, the Labour lead had started to narrow as the Tories regained lost ground.

It is often argued that the Tories’ increased support among ‘Northern working class’ voters in 2019 hinged on a perception of Johnson as being committed to ‘fairness’, to ‘levelling up’, and to better-funded public services - something that is supposedly anathema to mainstream “small state” Tories. Some have even claimed that the social and economic necessities of the pandemic are forcing a break with neoliberalism, citing the fact that UK government spending rose to 52 percent of GDP in 2020-21, and that Johnson has raised taxes on the working-age population in an attempt to fund the NHS and social care. But Johnsonism is by no means anti-neoliberal, and, even if he were deposed, the Tories would remain in a position of strength. Rishi Sunak’s Spring Statement – which failed to act on the cost of living crisis – is further evidence of the Tories’ unwillingness – or inability – to break fully with the old consensus.

The real glue keeping the Tories’ electoral coalition together is not big spending pledges, but the promise of protection offered by Johnson to his voter base – in particular, the implicit promise to protect housing wealth. Arguably, this unified bloc of homeowners – along with the absence of a meaningful political alternative – is what keeps both the Tories and the UK’s faltering neoliberal model on the road. The one thing that could seriously undermine the unity of this coalition is failure on the question of living costs—especially if these pressures reach far enough up the income ladder to hit older, often retired, outright homeowners.

The Conservative Base: Safe as Houses?

The Conservative Party’s electoral dominance is founded on middle-class homeownership. Ever since Conservative MP Noel Skelton coined the phrase in the 1920s, the fostering of a ‘property-owning democracy’ has been the means by which the Tories secured mass middle-class support. In the 1980s, Margaret Thatcher’s privatisation of social housing spread homeownership to new layers of the working class, and helped to create a new generation of ‘responsible’, conservative homeowners in the process. Homeownership has been identified with conservative views on the welfare state, while poorly performing regional housing markets are associated with increased support for populism in both Britain and France. Perhaps more than ever, Tory electoral fortunes are wedded to the performance of the housing market (which has recently entered a post-Covid boom).

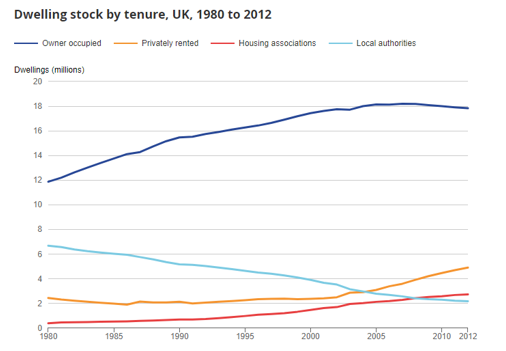

Although the emphasis on homeownership is not new, the political economy of housing as a financial asset has assumed new weight in the neoliberal era. As Colin Crouch has argued, the use of government fiscal policy to stimulate the economy was gradually replaced in the neoliberal era by policies that increased wealth through rising house and other asset values (so-called ‘privatised Keynesianism’). This highlights the way that the neoliberal project reformed and redefined class identities through the political economy of housing assets. The Conservatives have been most electorally successful under neoliberalism when they have effectively seized on structural processes to engender more conservative class attitudes among the wider population. But the strains of socio-economic under-performance since the 2008 crash – the political manifestations of which are most obvious in ‘populist’ revolts like Brexit – have forced the Tories to subtly adjust their pitch. Since the housing market downturn after the financial crisis, government lending (in the form of Help to Buy and other measures) has once again sought to directly stimulate house prices and thus increase household wealth. Yet housing has become an increasingly unstable basis for the legitimacy of UK democracy. Rates of owner occupancy have levelled off as younger generations have been locked out of ownership by rising prices, and the private rental sector has grown as public housing has been sold off. The Tories don’t need to promise much to the latter groups in order to preserve their electoral coalition. Rather, they need to make persuasive enough promises of protection to older homeowners in the face of obvious and difficult-to-resolve socioeconomic under-performance.

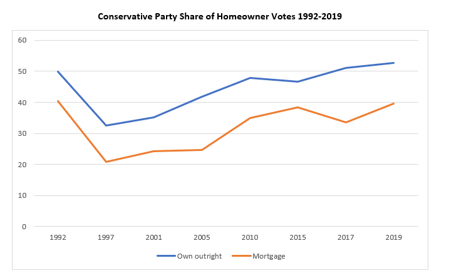

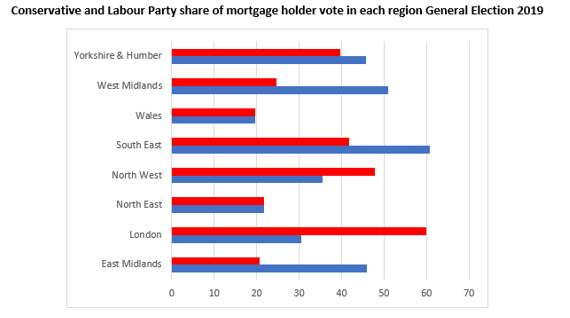

The often unstated, but nevertheless overriding importance of home ownership to the Tories is visible in the polling data. Data from the British Election Study shows that Johnson’s 2019 success did not wholly consist in reaching new areas of the Leave-voting, Northern working class, but in uniting homeowners across regions. Calculating votes among the two homeowning demographics – outright owners and mortgage holders – shows Tory support returning to levels last seen in 1992.

Data Categories Cross-Sectional Data - The British Election Study

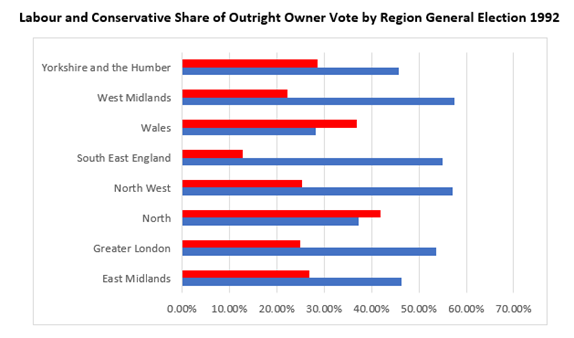

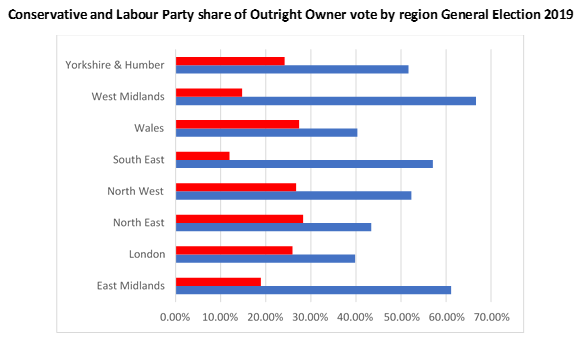

What has changed since 1992 (the last election at which the Tories won a large outright majority) is the regional spread of this vote. Calculating party support among outright owners across select regions shows the extent of these geographic shifts.

Data Categories Cross-Sectional Data - The British Election Study

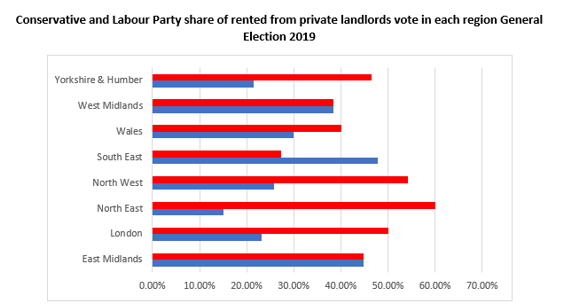

The Tory grip on mortgage holders is much less pronounced. Even in 2019, Labour won significant support amongst this group. Perhaps predictably, Labour beat the Tories amongst renters.

Data Categories Cross-Sectional Data - The British Election Study

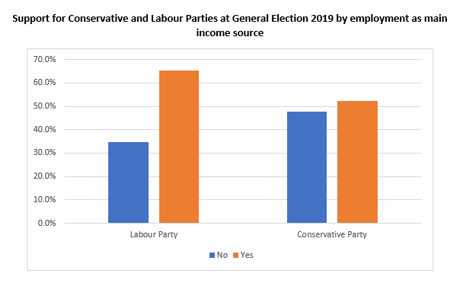

There is no automatic relationship between holding a mortgage and becoming a Tory voter. Mortgage holders benefit from low interest rates, while steady inflation combined with increasing wages erodes the real value of their debt. In this sense, mortgage holders can be distinguished from older, often retired outright owners. Claims that we live in an asset economy in which most households adjust their behaviour to conform with the imperatives of financial markets should be tempered with the understanding that mortgage payments are made from wages. Income from work still predominates in both the Labour and Conservative vote. Nevertheless, a large chunk of Tory support does come from older voters who own their homes outright and do not primarily live off the value of their labour.

Data Categories Cross-Sectional Data - The British Election Study

Many have been quick to identify shifting voter allegiances with a long-term change in ‘values’; that is, a move towards social conservatism and authoritarianism among former Labour voters in non-metropolitan areas. Coupled to this is the idea that ‘traditional’ (i.e., white) working class voters have abandoned Labour because of its perceived cosmopolitanism and focus on middle class graduates. Setting aside the Brexit effect of 2019, Labour previously won over poorer voters in 2017, and continues to do well among most groups of working age. The Tory Party did cohere all classes across the Leave bloc in 2019 – including, by any conventional measure, working class voters. There are plenty of valid criticisms of the ‘social grade’ measure of class (the famous ABC1 C2DE class schema) through which election data tends to be interpreted, but even if we look directly at the relationship between voting and income, Labour in 2019 also lost among most low-income voter groups.

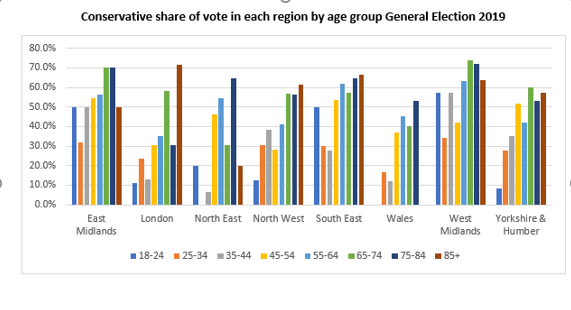

Class is a multifaceted concept for which many necessary conditions, but no sufficient set of conditions, can be abstractly identified. Class subject-positions depend not only on socio-demographic factors (one’s position in a stratified labour market; one’s relation to the means of production; one’s level of workplace and domestic autonomy; one’s racialised and gendered social identity), but also on factors involving time and place (periphery/centre relations; relations of uneven and combined development) and their combination with ideological factors (the culture and experience of time and place as it is expressed through public discourse). For example, it is sometimes argued that older voters tend to be more conservative. Naturally, it is not age per se that abstractly determines this effect, but the ways in which a range of factors – including so-called life-cycle effects (entry into the housing market; accrual of pensions and other savings) – reorient class identities and political perspectives over time. Moreover, where these established sociological life-cycle effects break down, the expected shifts in politics can similarly fray – as is often anecdotally reported among ageing Millennials today.

Absent the Brexit effect, many poorer Leave voters may well return to Labour, especially given their exposure to a weak economy. This is not to dismiss the ‘values’ divide, but to recognise that the salience of that divide was increased by Brexit, which cut across experiences of time and place in complex ways. Whether the homeowner effect can be similarly offset is less clear. Unlike poorer, younger Leave voters, older outright homeowners are shielded from some of the effects of an economic downturn through ring-fenced pensions. It is the convergence of homeowners across regions within the Tory Party fold that arguably makes the Conservatives today so dominant across England. Outside of England (and indeed within England’s larger cities), electoral politics appears more open—perhaps due in part to the aforementioned cultural and ideological, as well as complex time-and-space, effects on identities. We cannot assume, then, that the Brexit effect will continue to unite voters across classes at the next election. Rather, in 2019, the Tories re-cemented a version of their classic, older homeowning voter bloc across regions. The latter may prove more enduring than any increased working-class Tory vote.

Data Categories Cross-Sectional Data - The British Election Study

The composition of their 2019 coalition means that the Tories may not be under permanent pressure to increase state spending. Although a move towards a more equal society would be popular among all age groups, it is among the younger, working-age population that redistribution has become significantly more popular. Young, poorer Leave voters who went Tory in 2019 might desert them over this, but it is far from clear that the Conservatives would suffer decisively from the loss of this support as long as they maintain the regional spread of older homeowners. According to the 2020 Social Attitudes Survey, the working-age population increasingly favours redistribution to address social inequality, whereas older voters’ views haven’t changed significantly. The ability of Johnson to hold his 2019 electoral coalition together, then, may not depend on his ability to permanently boost state spending on public services. The vast majority of Tory voters continue to favour policies that benefit the older, wealthier, and asset-rich, while their ‘values’ continue to emphasise protection from outside threats, the importance of public order, and the maintenance of a disciplinarian state. The Tories remain by far the most effective electoral vehicle for these policies.

Keeping the Show on the Road

Beyond electoral expedience, there are other reasons the Tories have not permanently shifted away from neoliberalism and towards greater state interventionism. Analysis of socio-demographic factors can only take us so far in explaining this. Many of the economic tenets of Conservatism – and neoliberalism more generally – have long been unpopular, even if neoliberalism’s model of an entrepreneurial self has been accepted as an unfortunate fact of life; a hegemony depending, as Ralph Miliband put it, “not so much on consent as resignation”.1 In reality, political actors respond to popular pressures within tight constraints. Rishi Sunak’s lack of decisive action on the cost of living crisis is just the most recent case of the Tories failing to become the ‘party of big government’ in the wake of the pandemic. What characterises government policy to a great degree is a state project through which the deep purpose of government activity is presented and justified to the public: the provision of security from external threats and economic instability alike; the optimisation of the performance of key national assets (both public and private); the maintenance of domestic law and order. This state project must manage, within quite specific bounds, a regime of accumulation; that is, a particular configuration of social production and reproduction.

These may sound like complex concepts, but they can be readily understood if we return to the issue of housing. If the popular acceptance of neoliberalism was based on the promise of increasing middle-class wealth through privatised, financialised housing assets, successive governments have gone to great lengths since the financial crisis to protect and shore up that wealth. The list of policies is both long and familiar: low interest rates, central bank asset purchases (Quantitative Easing), support for buy-to-let mortgages, Help to Buy ISAs, and so on. Even prior to the onset of the pandemic, significant fiscal and monetary support for homeowners had already become a prevalent fact of life in post-crisis Britain. This was accompanied by commitment to a dominant service sector – particularly financial services – as a model of employment growth. Financialised and privatised social reproduction – for example, the creation of privatised housing assets – has, for those able to attain homeownership, offset the effects of an insecure jobs market. Externally, the increasingly forlorn hope is that a pivot to the simultaneous imperialism and Atlanticism of free trade will provide a boost to the City and a ripple effect across the jobs market. The power of the state to intervene to support rentier sectors through outsourcing, privatisation, and subsidy is readily mobilised. Thus, post-crisis change to the British state project has responded to pressures from within the neoliberal accumulation regime itself, as well as responding to some degree of ‘popular’ pressure (witness, for example, the ‘populist’ discontent with ‘elites’ that appears to have driven some part of the vote for Brexit).

Graph & Calculation Author’s Own

Compiled from individual survey panel data available here

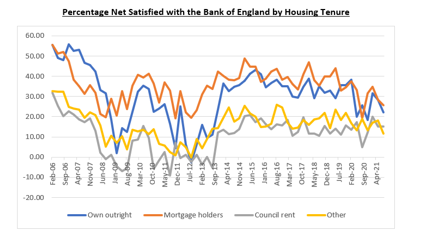

As evidenced by long-term low rates of satisfaction and trust in a range of public institutions, these efforts to shore up state project legitimacy have not been entirely successful. For example, following the financial crisis, public satisfaction with the Bank of England fell steeply, and has yet to recover. Although homeowners continue to express higher rates of satisfaction than renters, net satisfaction amongst all tenure groups has remained below 50 percent. This diffuse sense of dissatisfaction with, and alienation from, the state creates ample room for popular resentment and unrest. One of the contradictions of the last five years has been the manifestation of this discontent within the ruling party’s own camp. Time and again, Tory leaders have attempted. with limited success, to align themselves with the popular majority – the little guy, the small saver, the sensible homeowner – against various iterations of the cosmopolitan, foreign, liberal or technocratic ‘elite’. Rather than a ‘break’ with neoliberalism, this should be understood in both Wendy Brown’s and Melinda Cooper’s terms as its bastard offspring – a move towards the patriarchal authoritarianism of the nuclear family unit that was always latent in neoliberalism’s DNA. Even in its original Thatcherite iteration, neoliberalism emphasised both ‘individuals and their families’ as the alternative to social collectivism. It is thus a real modification of the state project (partially as a result of popular class effects), but nothing like the abandonment of that state project. The evidence for this is overwhelming: after ten years of profound political upheaval from the financial crisis to Covid by way of Corbyn and Brexit, very little of substance has changed in the make-up of British political economy.

A New State Project?

The idea of a state project is a relatively recent coinage. It comes from the work of Bob Jessop who, in his 2015 book The State: Past, Present & Future, lays out some foundational building blocks for a critical approach to ‘the state’ that draws on decades of theoretical work. Starting from the idea that the state is not a thing but a terrain of struggle, Jessop formulates the idea of a state project as that which ensures the minimal organisational coherence of the state. In the face of the various tensions and crisis tendencies that cut across the social formation, and the various apparatuses that make up the state system, the state project is the principle by which the institutional unity of the state is created and reproduced.2 State projects are the ‘sources’ of the state’s ‘legitimation’3 not only in that they ideologically integrate the ‘people’, but also in that they work materially and semiotically to render the state a coherent entity – a ‘whole’.

The neoliberal state project restructured class identities through the expansion of access to housing assets. But, in the fifteen years since the financial crisis, a wave of legitimation difficulties have confronted this project. Both real incomes and homeownership rates have stagnated in recent years. Chronic underinvestment in both private and public spheres has fuelled growing frustration. Particularly since the 2016 Brexit vote, the Tories have been repositioning themselves towards populism within the dominant state project, but they have not fundamentally altered that project. Their inability to shift the fundamental direction of state policy away from rentierism and the dominance of financial services is not only attributable to the interests of their super-rich donors. It is also a function of the constraints imposed on political action by the capacities of the state and the regime of accumulation it reproduces. Instead of breaking with neoliberalism, efforts have been made to shore up the support of homeowners, who are, nevertheless, ageing, shrinking in number, and harbouring resentments of their own. Sunak’s clear desire to revert to type – cutting taxes rather than raising benefits – has resulted in a bungled Spring Statement. Underlying this apparent complacency is both the Tories’ grip on older homeowners and their inability to break with the neoliberal state project.

Despite the litany of state failures and the growing resentment within their own base, Johnson was able to cohere the traditional – if regionally redistributed – Tory voting bloc in 2019. This was quite an achievement, and it means that the Tories should not be underestimated. Talk of the decline of the Tory Party is probably, once again, premature. Fantasies about a crisis which could finally split the Tories from their homeowner base should be avoided. Yet there are grounds for optimism in the medium term. Political scandals are amplified by lived experience of economic hardship. Working-class Leave voters may desert the Tories over rising energy bills, or any other politically explosive manifestation of economic under-performance. As we have seen, mortgage holders remain significantly less wedded to the Tories than outright owners. Even as some renters are transformed into (heavily indebted) mortgage holders, the right political project could see sections of the homeowning middle classes align with more traditional working class demands for a revived, inclusive welfare state and adequate redistribution.

Yet, as the alternative party of government, the Labour Party has done everything it can to rebrand itself as the more ‘sensible’ managers of the same failing state project now mishandled by the Tories. This means that a change in government would not, by itself, materially alter that state project. Furthermore, we should not bet against further adaptation by the Tories in future. Johnson is likely to fail sooner or later – that has, after all, been the one constant in his career. The failure of the Tories could follow, if their capacity for adaptation and their ability to cohere their base falters – but that is not a given, especially if they can keep homeowners relatively insulated from the emerging cost of living crisis. We should expect to see precisely this from the next Tory leader – whoever that may be. Labour has a slim, but by no means non-existent, chance of prising those voters away from the Tories. The replacement of the neoliberal state project, however, will take an effort of collective political will as yet unseen in British politics.