The Death of Stalin; very much a red flag to a bull.

The Death of Stalin; very much a red flag to a bull. Trainspotters of the Left will have noted that few of their favourite papers/websites/blogs with the word Socialist in the title have allowed Armando Iannucci’s latest offering to pass them by unremarked. Iannucci himself has built a deserved reputation for being a masterful satirist. The Thick of It, Veep, and In the Loop are pitch perfect take-downs of their subjects, beautifully absurd dissections of a world well known to us, but forever just out of reach. The Thick of It, in particular, arguably sets the template for unpicking the vapidity of Blairism in a way that I think has been key to its subsequent demise. When Iannucci turns his attention to ‘one of your boys’, it’s quite natural to want to sit up and listen.

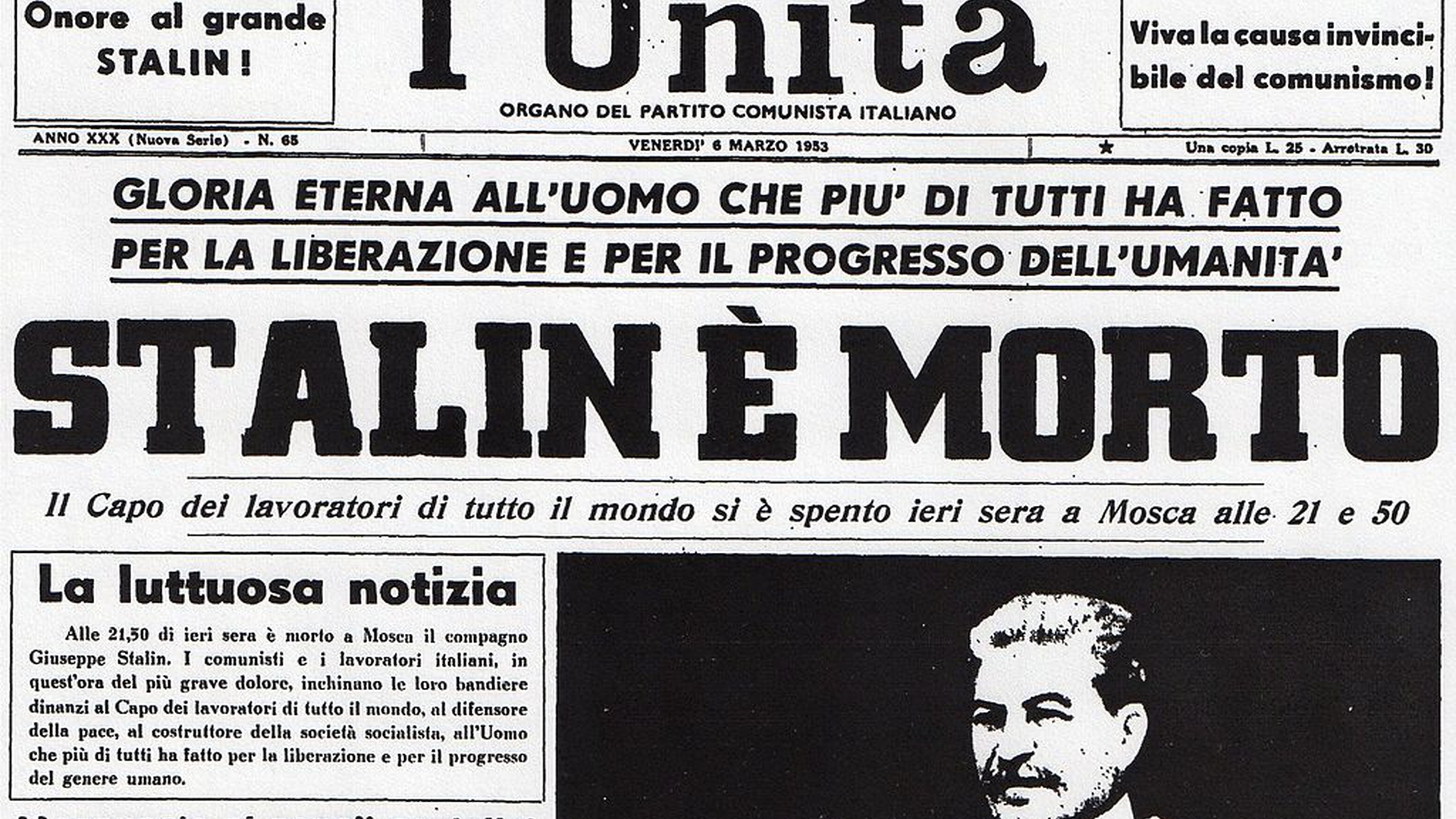

Of course, is Stalin one of ‘our boys’? It actually doesn’t matter all that much whether you answer that in the positive or the negative, or precisely how you feel about the assertion. The legacy of Stalin remains, in public discourse at least, a legacy of a monolithic ‘Left’ and, for the time being that shows little sign of abating. I suspect that this is how Iannucci feels about the subject (even if he might not recognise the terms), and that consideration very much colours the cultural undergirding of this film. To simplify, The Death of Stalin is no accident. The subject and the timing are precise: chosen as the old spectre of socialism haunts the world once more, the strong man leader is very much back in style, and, conveniently, we’re about to pass the 100th anniversary of the Russian revolution. Iannucci no doubt thinks himself very smart to have hit all these markers at once.

Of all those points, the one that should preoccupy socialists is of course the first. The film is probably most rewarding for us when read through the prism of what it has to say on the balance of politics in the here and now, vis-a-vis the histories and legacies of the left and the USSR. Would this film have been made were it not for all the current excitement about ‘KGB’ subterfuge in Europe and the US, the ‘new Soviet empire’, and ‘Putin did 9/11’? I think not, and it’s an important consideration. Likewise, I can’t see a release coinciding with the centenary of the Russian Revolution as anything less than an attempt to conflate that moment with the broad history and meaning of everything that followed. Russian history from 1917-present is, after all, a single event in the minds of our chattering classes.

I’ll resist the urge to wax lyrical as to historical accuracy specifically. Iannucci insists it’s more-or-less accurate and thoroughly researched; New Socialist frequenter Owen Hatherley begs to differ. I’m certainly not confident enough of my own knowledge to come down firmly on either side (though I think it’s pretty clear who would be the more trustworthy source). I don’t think it’s that important if we’re taking the film as a piece of entertainment rather than historical record. The issues here, as best I can tell, are with framing and nuance; omission and focus, rather than whole-cloth fabrication masquerading as fact. When we’re discussing a film that wrings every drop of humour from a dead man’s piss, I don’t think it matters too much.

Other concessions to the prejudices of the present are less forgivable. The strong tinge of Russophobia grates. Every character is a sycophant (Molotov) or a cynic (Khrushchev), or else a peasant carrying jars of pickled eggs and baskets of turnips. The latter is played straight and without a hint of irony, most notably in the opening scene where the manager of a concert hall frantically tries to fill out the acoustics of the room with passing peasants. “I doubt any of these people have even heard of Mozart” he grumbles as they fill their seats. Is that the manager talking or Iannucci? Being the Twitter-bound creature I am, it immediately called to mind the outrageously racist Louise Mensch outburst from last year- “there are no Leonard Cohens in Russia, they have no rock n’ roll, no fun, no Hallelujah, & they are poor in everything, including spirit”. No Leonard Cohens (and I’m fairly sure that’s not true), but plenty of Dostoyevskys, Rachmaninoffs, Lissitzkys. They only invented two entire visual languages underpinning modern cinema and the graphic arts. No biggie. The artless Slav is a trope that refuses to die, and it’s on fine form here. It’s ugly.

In a similar vein, the film’s relationship to the working class – who, historically speaking, are nominally the stars of the show – is also fraught with difficulty. The casting of Paul Whitehouse, an actor who made his mark as a smart working-class voice in comedy, as Mikoyan, left me feeling more than a little conflicted. He’s joined by Adrian Mcloughlin, giving Stalin a hint of Brick Top; Steve Buscemi, doing a nasally Khrushchev with a New York twang; and Jason Isaacs whose Zhukov appears to hail from God’s own Yorkshire. The choice to have actors mostly deliver their lines in Anglophonic accents – rather than affect cod Roos-ian – is welcome, but it foregrounds the class dynamic to an English-speaking audience in a way that may have not otherwise been quite so apparent. It’s not the only film to use this technique: Enemy at the Gates has Bob Hoskins play Khrushchev as a right ‘ard geezer in order to establish clear class lines between the grubby prole Soviets and the duelling-scarred Nazi aristocrats. However, where Enemy at the Gates benefited from the fact that it was making the comparison somewhat flattering (sorry, Telegraph columnists, Nazis still look like go-to bad guys), here there is more than a hint of “this is what happens when you leave the plebs in charge”.

Considering Iannucci’s rather disappointingly liberal-technocratic politics it’s hard not to see it that way (it’s easy, if you are a pleb, to forget that The Thick of It is as much an affectionate ribbing of the ruling class as it is a spittle-flecked Malcom Tucker dressing-down). Whitehouse, who does a perfectly serviceable job, seems slightly out of place amongst bigger names like Buscemi, Jeffrey Tambor (Malenkov), legends such as Michael Palin (Molotov), and thesps like Simon Russell Beale (whose Beria is wonderfully toady). Whitehouse is a figure caught in a weird twilight zone of celebrity- not quite famous enough to punch with the big guys, too famous to quietly fill out his secondary character role. That’s not to take anything away from the man, but rather to highlight that it seems to strongly indicate the casting was deliberate, as opposed to ‘who can we get to fill out that role?’ Likewise, perhaps more obviously, Jason Isaacs’ ‘Yerkshire’ brogue is clearly not a happy accident. The incongruity of Zhukov, the peasant-boy done good, with a chest full of medals and gold-trimmed general’s uniform, but who can’t quite shake the mannerisms of his no-nonsense upbringing, is funny enough, but it’s intellectually lazy in a film in which class is implicitly a thematic point. While we always want to see more working-class voices in cinema, we shouldn’t be blind to the deployment of class in less-than-classy ways.

Then there’s Palin. Why is he there? Again, nothing to complain about in the performance, but Palin, as part of Monty Python, made a fair bit of hay out of the ‘loony left’ in his day. It’s not for nothing that those famous Monty Python gags - “The People’s Front of Judea!? Fuck off! We’re the Judean People’s Front” etc. (ruined for all eternity by Centrist Dads thinking they hold the key to understanding/dismissing the Left) - weren’t delivered in the actors’ native plummy public school/Oxbridge accents. The target then (perhaps not unjustly) was the Left, and (less justly) the wider working class. The same message resonates there: “this is what happens when you leave the plebs in charge” – sectarianism, infighting, mind-numbing proceduralism. Casting Palin, here without the accent (and make of that what you will), but very much situated as the only bonafide true-believer, is a callback to his earlier work. To that end, true-belief is conflated with sycophancy and stupidity. It’s hard, as a communist, not to take some umbrage at the rather tired assumption.

That then leads us to the film’s central flaw: it’s not The Thick of It. In the razor-sharp world of high-point Stalinism power-plays, Iannucci is out of his depth. In The Thick of It, it seems reasonable to assume that Iannucci is generally familiar with his base material. We all are to some extent – we digest the trials and tribulations of that world live, as they happen. We probably don’t know the ins-and-outs, but we can construct reasonable facsimiles in our heads. The Thick of It plays with that: it fills in the blanks between policy announcements with familiar minutiae. The Offices of State are offices, replete with watercooler gossip and misplaced memos and all. That’s the joke – the cynical bunch of shits filling the halls of power are eminently relatable in their cynicism and shittiness. How would you replicate that in the 1950s Kremlin? When the stakes are that high I’m not sure you can, and I’m not sure you should.

The problem is complicated by the fact that Iannucci is totally unsympathetic, hostile even, to this world. Little did we know at the time, but it was precisely because Iannucci viewed the petty bickering in Whitehall as the best worst system, that he was able to pick over it with a fine-tooth comb and really tease out those moments of plausible absurdity. Stalinist communism repulses Iannucci; it’s irredeemable. That’s not really a criticism of him, but it does mean his formula doesn’t work quite as well. This is most glaring in the case of Beria, who is otherwise one of the best (worst) characters in the film. Iannucci alludes early on to the allegation that Beria was/is a rapist and paedophile, serially abusing his power in the NKVD (secret police) to satisfy his abominable habits. Is that funny? Iannucci doesn’t play it for laughs, but even so it’s there, in an otherwise somewhat comically villainous character. Iannucci wants to use these little sketches to cast a moral seriousness on his Dads’ Army approach to the politburo, but it doesn’t fit. When, on the eve of Beria’s arrest, he begins to out the crimes of fellow politburo members, (‘Khrushchev signed this many death warrants, Molotov this many etc.’) the film wants you to tut along and to chide you for ever sympathising with cynical Khrushchev - ‘ah, they’re all as bad as one another’. Do you feel a pang of guilt as Beria is frogmarched unceremoniously from the impromptu trial to his execution? The film wants you to, I think; it wants you to reflect on how terrible this all is, how awful these men are. How awful these men are, who we’ve just spent two hours laughing at? The film wants to have its cake and eat it. It’s at these moments that the film can’t actually decide whether it wants to be farce or historical record; if it pips for the former, it perhaps does so only at the last minute.

In essence, Iannucci has failed to escape the gravitational pull of his orientalist ignorance. He doesn’t want to bother learning his subject; but he also wants to offer moral pronouncements upon it. It’s symptomatic of much deeper trends in the west; circling back to that undertone of Russophobia. Iannucci is doing a Mensch, albeit a much less stupid one. He never interrogates any of the complexities of the situation. Again, he shouldn’t need to – shorthand is the bread and butter of comedy – or rather he wouldn’t, had he not tried to blur the line between comedy and docudrama quite so haphazardly. You don’t need to be an expert on the history to spot wide-open gaps in the narrative being presented. Why do the thronging crowds fall into chaos as they flood Moscow for the funeral of Comrade Stalin? Are they just dupes of a personality cult? Is there something real to their adoration? The enduring popularity of the man inside Russia, problematic as it is, suggests there might be.

And why include Stalin at all? We get a tantalising glimpse of the most historically-interesting character in the film, but Iannucci doesn’t seem to want to do anything more with him than say “what a bad man” and then kill him off. You would presume that this is the go-to opinion of most audience members, so why not just start the film with him recently dead and shave a few minutes off the runtime? In respect of that, the comparison has been made between this comedy and the far greater number made about Hitler. It’s true, Hitler has been ripe for (black) comedy for a very long time, but I don’t know of one that takes itself quite so seriously? One that takes place in the bunker? If it exists, is it funny?

I’ve made it sound like I hate the film: I don’t. It’s a perfectly entertaining piece of comedy. It has a few belly-laugh moments which call back to The Thick of It‘s better moments. Khrushchev trying to swap positions with Malenkov around the departed leader’s coffin, and incorporate this pettiness into some kind of sombre ritual, is a great moment of physical comedy. Some seemed unamused by Stalin’s piss (his brain haemorrhage causing him to relieve himself as he keeled over); I thought it was perfectly funny seeing the pantomime cries of mourning politburo members interrupted by the realisation that they’d just knelt in a pool of Koba the Dread’s wazz. It was funny when he ended up being rolled – soggy crotch first – across Paul Whitehouse’s face.

The points I pulled out above are personal quibbles. I don’t think The Death of Stalin adds anything to the ongoing public debate about the legacy of actually-existing socialism, so recently reignited by a string of left-wing springs across the western world. I don’t think it even adds anything to discussions on the re-emergence of hyperreal, hypermasculine, strong-man politics (Trump, Putin etc.). I think it wants to (The Guardian‘s Peter Bradshaw seems to think it’ll give Putin’s cronies sleepless nights – sorry, but no, but it fails to do so, albeit without actually bringing the film down with it. It’s certainly for the best, all indications being that all Iannucci has to offer on the subject is regurgitated commonplace truisms and a simplistic liberal narrative well past its sell-by date. Most of the film’s observations are thirty years too late. Its yuk-yuk-yuk parodies of pedantic, formalistic Leftism (“don’t move the body until we’re quorate”) would’ve been razor-sharp when Citizen Smith, Rick from The Young Ones and The Life of Brian were relatively fresh in folks’ minds. They now arrive at our shores toothless, harmless, in no small part due to the kind of much cleverer, much more biting critiques of managerial Blairism offered by The Thick of It and its ilk. The world in which Iannucci was forged is now fading fast. It shows – good riddance, long live the new flesh – but it doesn’t mean he can’t give you the odd laugh in the meantime.