What was Militant, and why does it still upset certain people so much?

When the hapless, perma-briefing ‘former Shadow Chancellor’ Chris Leslie faced an unsurprising vote of no-confidence from the members of his Nottingham constituency, it was inevitable he would use the ‘M’ word. He’d seen it all before – Momentum were the ‘Militant of the digital age’. Praise of the ‘Militant-led’ Liverpool Council of the 1980s by Dawn Butler, and the alleged re-admission to the Labour Party of its leader, the talk radio host and property developer Derek Hatton (who left Militant thirty years ago) caused the usual media handwringing, with various figures of the sensible centre-left sharing Neil Kinnock’s 1985 conference speech aimed at Militant’s ‘impossible promises’, a pivotal moment where the fightback against a now bafflingly resurgent ‘hard left’ began. The broadcaster Michael Crick has resumed his 1980s role as Militant hunter, even revealing that Labour’s General Secretary, Jennie Formby, had briefly been a member of the clandestine organisation. The loudest journalistic voice of the Labour left, Owen Jones, comes from a Militant family, something seldom lost on his many enemies. A quick Google of ‘Corbyn Militant’ can find you the current Labour leader opposing the purge of that organisation from Labour in the 1980s. What does it all mean? What was Militant, and why does it upset these people so?

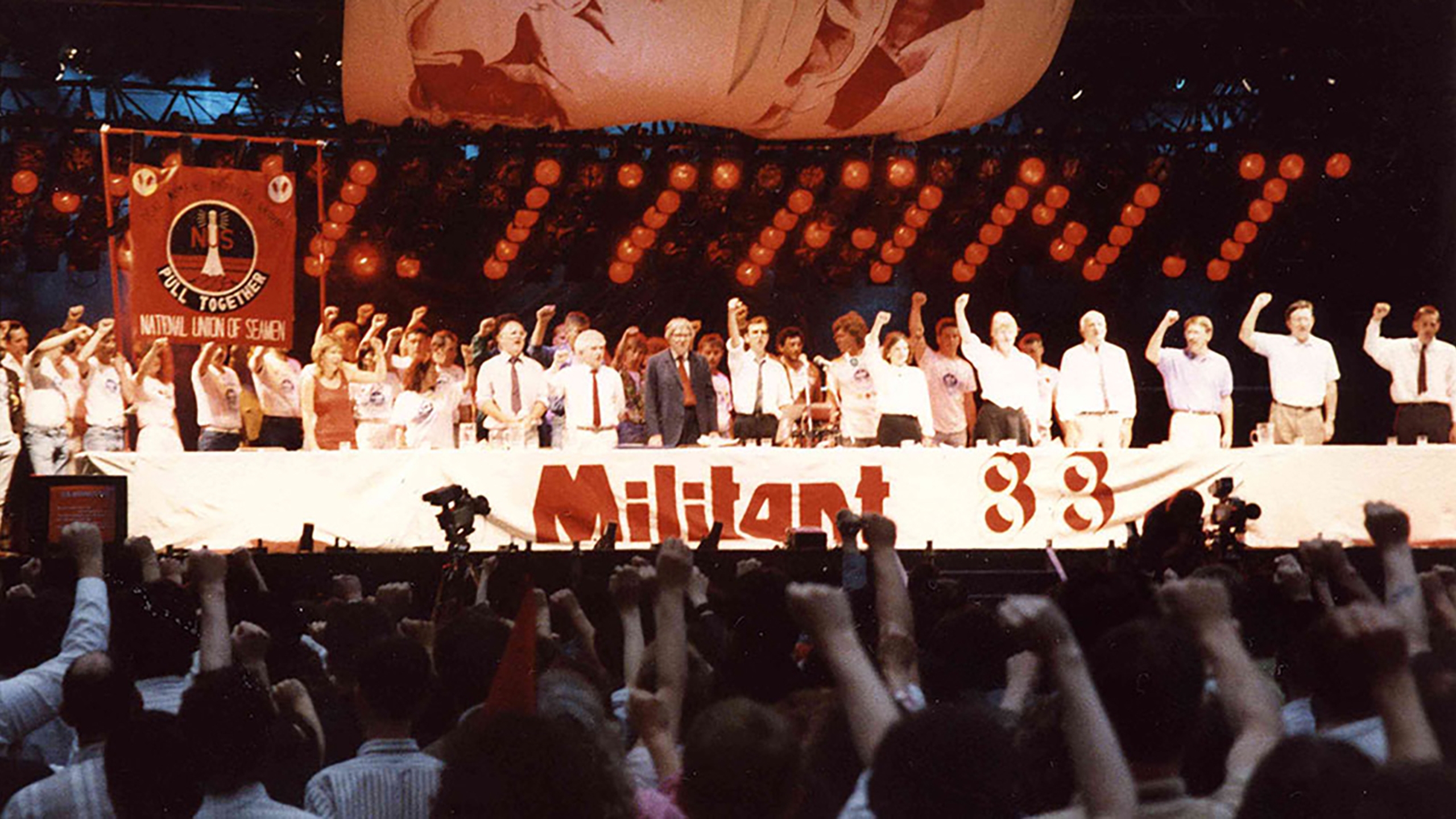

Neil Kinnock once made a distinction between what he called the ‘legitimate left’ in Labour – the traditions associated with names like Maxton, Bevan and Benn, radical social democrats from within the mainstream Labour movement – and the ‘illegitimate left’ that came from without, from the Marxist organisations that, uniquely for a European socialist party, had never been part of the mainstream – the Communist Party and the 57 varieties of Trotskyists. Militant represents the time that the ‘illegitimate’ became most influential on the thinking and actions of the ‘legitimate’ British Labour movement. There’s no doubt at all that Militant came to Labour from without, although a member in the 1980s was bound by Leninist discipline to deny this. ‘Militant’ was the Revolutionary Socialist League (RSL), one of several splits from the briefly unified Trotskyist Revolutionary Communist Party. The RSL had decided to follow French Trotskyists into the mainstream party of the left, a process called ‘entryism’. Led by the Russian-Jewish South African Ted Grant, born Isaac Blank, and with an inner circle dominated by working class Liverpudlians, the small group joined Labour en bloc in the early 1960s and built quietly and steadily until by the end of the 1970s it controlled the Labour Party Young Socialists, so effectively having the pick of young activists. A few years later it had three MPs, Dave Nellist, Terry Fields and Pat Wall, and led Liverpool City Council; Crick estimates it to have been, in membership, the fourth largest party in Britain in the ’80s. Yet officially, it didn’t exist – these were just people who supported the line of the Militant newspaper. When Michael Foot moved to purge the RSL in 1982, he expelled the paper’s editorial board.

But what did Militant actually do? Here, memories all hinge on an apparently appalling stewardship of Liverpool City Council between 1983 and 1987, setting ‘illegal budgets’ which culminated in taxis whizzing round the city handing out redundancy notices to council workers. The truth is less dramatic. Liverpool was one of many councils that were ‘rate-capped’ in the 1980s by Margaret Thatcher’s government because their spending to alleviate the profound poverty her policies were causing went beyond what that government was willing to allow them. These councils included the Greater London Council and various London boroughs, Sheffield, Basildon, Leicester, Swindon, the Metropolitan Councils of South Yorkshire and Merseyside, and even Tory Portsmouth. Most of these were dominated not by the ‘illegitimate’ left, but by the ‘legitimate’ forces around Tony Benn, and the New Left influenced currents around Ken Livingstone. It’s notable that the legitimate/illegitimate distinction was rejected, and at first, a united front was presented. Yet when Thatcher refused to budge, two councils – Liverpool and non-Militant Lambeth – refused to set a legal budget; the ‘taxis’ that went round handing out ‘redundancy notices’ were the result, although the redundancy notices were false, as council workers and Neil Kinnock were made fully aware, and nobody was sacked. Nonetheless, as a result of the illegal budget 47 Labour councillors were fined and formally barred from office in 1987. Not that legality did the other councils any favours. The GLC, and all the other Metropolitan Councils across the country were literally abolished, and it took most inner cities well over a decade to recover from the ravages of Thatcherism’s initial offensive.

These rebellious local authorities were the mythic domain of the ‘loony left’, targeted with a relentless campaign of ignorance and bigotry by the tabloid press and the Labour right for their focus on fighting sexism, racism and homophobia as much as for their efforts to counterbalance Thatcher’s attack on workers rights and the welfare state. The shift in values since has made the 80s GLC something of a cult for Corbynite intellectuals, showing a plausible intersectional path for a radical social democracy. That doesn’t apply with Liverpool, and not just because they were officially revolutionaries rather than social democrats. Generally disinterested in anything non-economic, something they shared with Old Labour and Trotskyisms past, Liverpool Council fought on what would no doubt today be called ‘doorstep’ issues – largely, housing and unemployment.

That’s unsurprising, given that Liverpool was in deep crisis at the time. The ‘Militant-led’ (in reality, most of the 47 councillors were not members1) council was focused on job creation and training, and a massive building programme, ranging from leisure centres to youth clubs to parks, and the demolition of huge swathes of 20th century council housing, replaced with popular new single-family houses. In fact, when it came to anything more experimental or modern, Militant were extremely dismissive. Their greatest scandal aside from the ‘taxis’ was the appointment of a Militant member from London, Sam Bond, as the council’s Race Relations Officer (like Kinnock, Militant opposed the movement at the time for Black Sections), something which infuriated previously sympathetic community organisations in Toxteth. Similarly, the thousands of houses they built were straight-up rented from the council local authority housing, with GLC-style solutions like Housing Associations and Co-Ops, such as the ‘Eldonian Village’ near the docks, considered a distraction from the main goal of sorting out the city’s appallingly dilapidated mass housing.

Probably, things could have been done differently, with less confrontation. With hindsight, many of the tenements and high-rises Liverpool Council demolished could have been renovated rather than condemned, as the example of London or Glasgow at the same time makes clear, and that could have saved the council a lot of money. Much of what they did build was suburbs in the inner city, making the anti-urban panic of the 80s into something permanent. But it bears repeating that the ‘illegal budget’ had nothing much to do with the comically hard-line policies that Militant favoured at a national level, where at conferences and party meetings a Scouse (or faux-Scouse) voice would demand, hand chopping the air, ‘an enabling act to immediately nationalise the top two hundred monopolies without compensation’. In Liverpool, Militant policy was based on trying to save the city from collapse, and many of its policies, especially in housing, were actually continued by subsequent Liverpool councils, though without the increase in politicisation that came with their propagandistic, mass-mobilisation approach to local government.

Somebody once called Militant after it was thrown out of the Party ‘Labourism in exile’, and you can see that in the way that it refused any politics other than those of the purest bread and butter, with any other change postponed to an ‘after the revolution’ – revolutionary rhetoric and reformist practice. Give the people what they want, and damn the government; even their slogan, ‘better to break the law than to break the poor’, was consciously borrowed from the ‘legitimate’ Rates Rebellion of Poplar Council in the 1920s, led by future Labour leader George Lansbury - as if the mask ate the face. It is possible that some in Militant’s leadership, sorry editorial board, considered this all just brinkmanship to ‘intensify the contradictions’ in British capitalism, but most Liverpool councillors evidently did not. So we have to ask the question again: what it was about Militant that so terrifies the media and the centrists of 2018, if it was just doing what left-leaning Labour councils had always done?

One answer is in what it did next. While being expelled en masse from Labour, Militant moved on to organising against the Poll Tax, the outrageously iniquitous flat tax ‘community charge’, imposed in Thatcher’s third term. The mass non-payment campaign – at one point, with estimates of 14 million non-payers – was devised by Militant, and the Anti Poll-Tax Unions that orchestrated the campaign were a Militant front. This huge and now mostly forgotten act of civil disobedience, helped of course by the Poll Tax Riots of 1990, was more important in Thatcher’s overthrow by a panicked Tory cabinet than anything else. By the end of the 1980s, Militant could say, with only a hint of hubris, that they had brought down Margaret Thatcher. No other organisation left of Labour can claim anything like this, and the MI5 files on Militant members must accordingly be voluminous.

This makes what happened next all the more sad. Essentially forced out of Labour, most of Militant’s members, inspired by the electoral success of one of its members, the jailed anti-Poll Tax activist Tommy Sheridan, voted to constitute themselves as a Party, first called Militant Labour, then the Socialist Party (a tiny group around Ted Grant stayed in Labour under the name Socialist Appeal, despite the fact most of its leaders had already been expelled). Although the resulting organisation would make some efforts to move on from the workerism that had marked it in the ’80s – one of its first front organisations was a Campaign Against Domestic Violence - outside Scotland, that’s really where the story ends. Socialist Party of England and Wales leader Peter Taaffe has just published an immense volume about the first ten years of the ‘SPEW’, with a second volume still to come, a monument of bizarre self-importance given the negligible influence the organisation has had. Of course there was no easy way to be a socialist in the 1990s and 2000s, but the fact is that the Socialist Party’s involvement in the Lindsey oil refinery strike of 2009 is about the only time it was noticed outside the far left. Scotland, thanks to the Scottish Parliament’s Proportional Representation, was for a long time a different story, and the Scottish Socialist Party was an important force until eventually capsized by a tawdry sex scandal around Sheridan’s enthusiasm for swinging and fake tanning booths. Its demise leaves a still unfilled gap in the Scottish radical left.

And in terms of ‘entry’ into Corbynism itself, Militant itself – its paper, The Socialist, now had under its masthead ‘formerly Militant’, to reflect the renewed interest in the organisation – has been cautious. The Socialist, £2 ‘solidarity price’, with its constantly renewed headlines of STOP THE CUTS and KICK OUT THE TORIES seems superfluous if you can get the Skwawkbox for free. Yet the two Trotskyist groups that did try entryism into Momentum – the Alliance for Workers Liberty and the Anti-Capitalist Initiative - both became influential in it very quick, before being purged by the leadership around Jon Lansman (their apparent belief that they deserved to lead the new organisation after a few months of packing meetings contrasted rather sharply with the Revolutionary Socialist League’s more patient, Le Carre-like mobilisation). Instead, the Socialist Party has tried to publicly affiliate to Labour, seemingly expecting to be welcomed back in a blaze of glory, while at the same time standing candidates against Labour in their Trade Union and Socialist Coalition with the Rail Maritime and Transport Union, and opposing the RMT’s re-affiliation to Labour. Needless to say, their ‘application’ was rejected by Jennie Formby, ex-member or not. The obvious solution for the SP of doing what the RSL did in the 1960s, officially dissolving itself while maintaining a network around their newspaper, would amount to admitting they were wrong in rejecting Labour in the 1990s. But then who wasn’t?

Really, the fear of Militant is about something quite different. It isn’t about the noisy but tiny remnants of British Trotskyism, and it’s not about nationalising the top 200 monopolies, or illegal budgets, or council house building in Liverpool, or even about the Poll Tax. It’s about that distinction that Kinnock made between the left that mainstream politics in Britain finds acceptable – working patiently within the Mother of Parliaments, frequently content with heroic defeat – and that which it finds unacceptable, that is equally comfortable with civil disobedience and distrust of our venerable institutions. Patently, Momentum is not much like Militant – it isn’t a secretive, clandestine organisation, and it emerged precisely from within the ‘legitimate’ left around the veteran Bennites. But most Momentum members would surely reject being told what which parts of the left are legitimate and which are not, and would consider direct action as being as ‘legitimate’ as waiting for the next Labour government. That’s why the spectre of Militant hangs over it.

-

On this, see by far the most serious book on the period, Diane Frost and Peter North’s Militant Liverpool: A City on the Edge (Liverpool University Press, 2013). ↩