The province of Northern Ireland has been continually raised as a spectre during the election campaign and is now once more on the forefront of the political agenda.

The province of Northern Ireland has been continually raised as a spectre during the election campaign and is now once more on the forefront of the political agenda. Not because its government hasn’t functioned since February, not because of its high levels of poverty, high rates of unemployment and low living standards, with some of the most deprived neighbourhoods in the UK, but because some of the MPs categorised within the “Northern Ireland” 18 parliamentary seats will be propping up the Conservative government.

Despite the fact that these 18 seats are depicted in statistics as a sideshow, grouped together rather than by party name, this is far from the first time that parliamentarians sent from Northern Ireland to Westminster have played a fundamental role in the machinations of government. In 1979, the SDLP’s Gerry Fitt refused to support the then Prime Minister James Callaghan’s vote of confidence because of the repeated allegations of brutality in the Royal Ulster Constbulary’s interrogation centre at Castlereagh – Callaghan lost the vote by one and the subsequent general election to Margaret Thatcher. In 2008, Gordon Brown and Harriet Harman made a deal with the DUP for their support for a counter-terrorism measure to increase detention without charge from 28 days to 42 days – which subsequently failed to get through the Lords – by backtracking on plans to extend the 1967 Abortion Act to Northern Ireland. Women who live in those six counties, who nevertheless pay into the NHS, do not have access to abortion and face prosecution and imprisonment if they seek it under legislation dating from 1861, and if they choose to travel to Britain, are required to pay for NHS abortions.

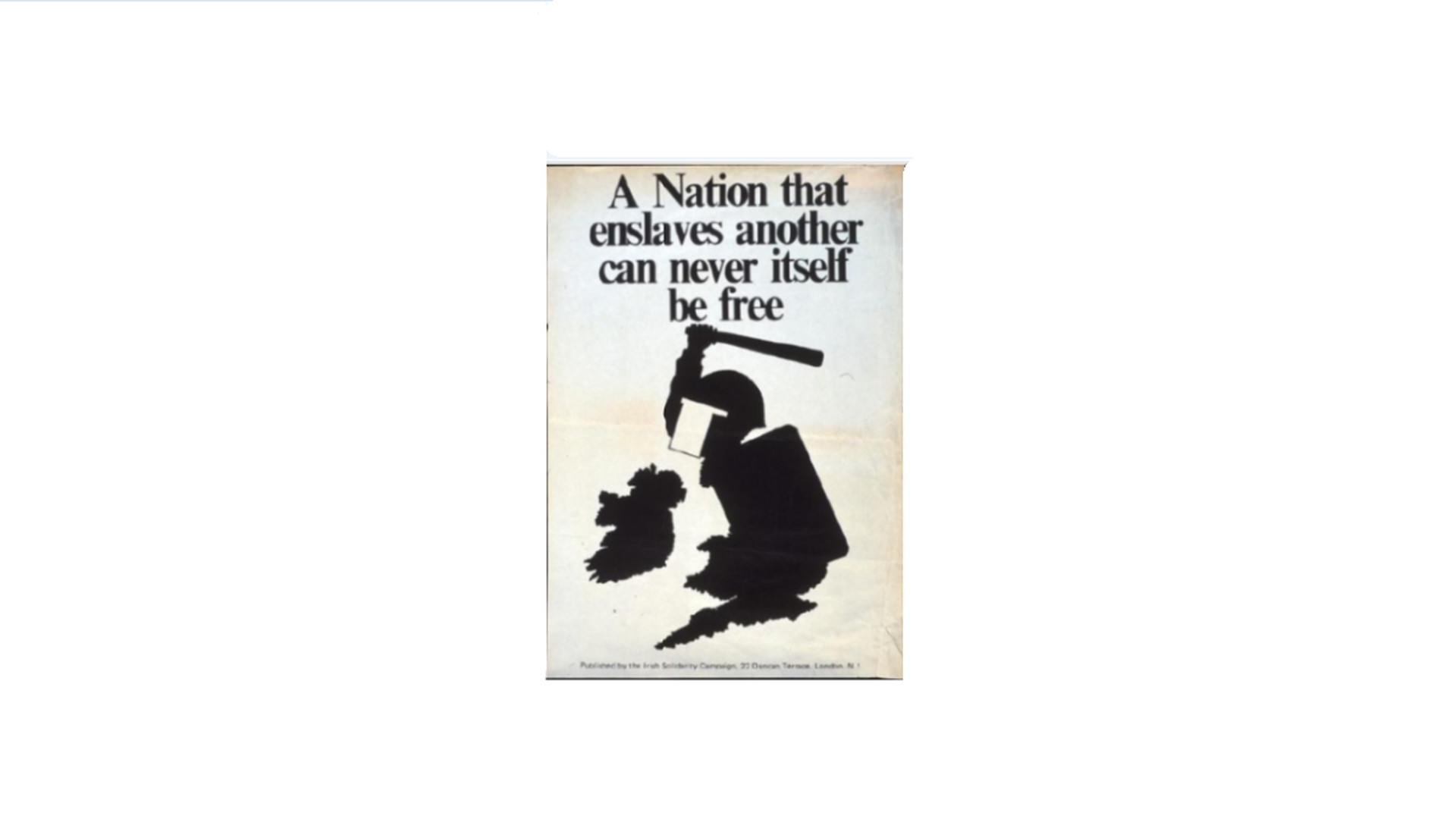

What is striking about the potential for the DUP to be propping up the flailing Tory government is that is encapsulates the utter constitutional mess of the post-conflict settlement in Northern Ireland. More significantly, it demonstrates how the continued British occupation of Ireland is a hindrance to socialism across these islands. As the maxim goes, a nation that oppresses another can never itself be free.

Whilst the Good Friday Agreement lends credence to the neutrality of the British state in its relationship to the quasi-autonomous governing parties in Northern Ireland, the dominance of the Conservative Party undermines this in its relationship with Ulster unionists. Its full name after all is the Conservative and Unionist Party, and in the past it has stood under a joint ticket with the Ulster Unionist Party. Subsequent British governments oversaw, to a greater or lesser extent, a military policy in Northern Ireland which strengthened links between security forces and loyalist paramilitaries. Loyalist paramilitary groups like the Ulster Defence Association (UDA) and Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) were used by the British in their dirty war against both armed republicanism and broader pro-republican civil society groups, with a high proportion of state and loyalist casualties being civilians (54% and 87% respectively). Undeniably, the political wing of loyalism gained a massive strategic and propaganda coup when the British military refused to break the Ulster Workers’ Council strike of 1974, killing off the more mainstream reformist Ulster unionism and its attempts at power-sharing under the Sunningdale Agreement. Clearly, British state forces had existential reasoning for its relationships with loyalist paramilitaries, but the Conservative Party found its ideological partner in some of the more extreme elements of Ulster loyalism – Vanguard Unionist leader and former Minister for Home Affairs William Craig visited the Conservative Party’s infamous Monday Club in 1972 to declare that he was prepared to ‘shoot to kill’ in defence of Ulster. The following year, just 8 months before loyalist bombs in Dublin and Monaghan caused the bloodiest day of the Troubles, Craig repeated this affirmation of extra-judicial murder along with a call for ‘direct action against business people and holiday-makers from the Republic’.

Notwithstanding the British state and the Conservative Party’s longstanding attachment to the cause of Ulster unionism and some of its shadier branches of virulent and violent loyalism, the current juncture should be understood as a reformulation of this political tinderbox, thanks to the intersecting constitutional crossroads that have come to a head after years of stultification, obstructing the potential for Anglo-Irish relations to be resolved once and for all. An informal governing arrangement between the Tories and the DUP will help to embolden the DUP’s voice at a time when the power-sharing arrangements in Northern Ireland are under a great deal of strain. Attempting to placate the DUP with financial bungs as a form of confidence and supply will further embed unionist rule at the expense of nationalists as the former present themselves as the gatekeepers of investment and governance in the region. After the collapse of Sunningdale in 1974, the unionists were able to hold the threat of an Independent Ulster arrangement, inspired by Ian Smith’s Unilateral Declaration of Independence in Rhodesia over the British government, who responded with continued industrial investment at a time when it was disappearing across Britain; indeed, two months after the strike the Harland and Wolff shipyards were nationalised at a time when government subsidy to shipyards in Britain was being cut.

The inertia of Northern Ireland’s state mechanisms are nothing new, although the current situation is symptomatic of much longer-term causes, not least those outlined by the likes of Nairn and Anderson that the British state is an anachronism (an ‘indefensible and unadaptable relic, not a modern state-form’) that survives having failed to fully deal with issues of state and sovereignty that led elsewhere to the birth of the modern nation states.1 In line with the so-called revisionist historians of the British Empire, I’d also include the continued failure to fully account for British imperialism and to deal with decolonisation, which has arguably not been concluded let alone confronted in the national psyche. The more medium-term causes include demographic and generational shifts that have contributed to the ascendency of Sinn Féin, namely the growth of the Catholic population and the increasing disassociation of new members of Sinn Féin with republican paramilitaries. In February the Stormont executive broke down and the subsequent assembly elections resulted in a loss of a majority for unionists for the first time since the inception of the state in 1922. Talks to come up with a power-sharing arrangement for the executive stalled and failed, and the governance of the province is still in limbo, with the dark cloud of direct rule hanging over it. There were a number of reasons for the breakdown of the government and subsequent stalemate, including Arlene Foster’s responsibility for the Renewable Heat Incentive scandal and failure to accept the blame, the refusal of the DUP to honour the rights of the Catholic minority through an Irish Language Act, and one of the most concerning aspects which was the lack of provisions given to the legacy mechanisms provided for in the Good Friday Agreement.

When Jeremy Corbyn refused to be coaxed into condemning IRA violence in isolation, he was merely fulfilling the principles set out in the Good Friday Agreement – one of the central tenets was in providing equal access to justice and recompense for all communities and all victims of the conflict, rather than prioritising and creating an unjust hierarchy of victimhood, a hierarchy that had dominated media and political discourse around the conflict since it flared up in 1969. There are fair accusations to make that the Good Friday Agreement did this insufficiently and imperfectly by further entrenching sectarianism, but the main thrust of it dealt with a situation which was hitherto prioritising an archetype of victimhood at the expense of others, effectively erasing the victims of state violence. The Saville Inquiry into Bloody Sunday has been one such recompense; others include the establishment of Historical Enquiries Team and police ombudsman to investigate unresolved murders. These were not entirely adequate – in 2013 the HET faced criticism from the independent police inspectorate for not investigating deaths caused by the police or military with sufficient rigour, no doubt thanks to the revolving door of retiring officers of the now-defunct RUC finding employment in the HET or Legacy Support Unit. The HET was dissolved in 2014 thanks to a 7% policing budget cut, despite the fact it had made public documents that shone light onto a number of atrocities involving British state collusion including the McGurk’s Bar bombing and the activities of the notorious Glenanne Gang, a UVF death squad who killed mainly Catholic civilians with assistance from UDR and RUC Special Patrol Group and Special Branch officers.

Progress has been sluggish, and there are many cases in which truth and justice is not forthcoming. The Dublin and Monaghan bombs – the most fatal attack during the entirety of the Troubles – is widely believed to have involved security force collusion tied to the Glenanne Gang, and yet the British government refuse to hand over key documents. This lack of recourse to justice for victims of state violence is a real grievance, and coupled with a British government that wishes to grant amnesties to British soldiers and openly attacks human rights lawyers who attempt to hold them to account, compounds the stalemate that currently incapacitates Stormont. It also adds to the state’s deniability of its role as combatant, something which the Conservative Party has seemingly put front and centre of its policy in Northern Ireland. The Good Friday Agreement is reliant on the goodwill of all participating parties, including the general populace which includes a high proportion of people suffering from trauma, family bereavement, adjusting to life after imprisonment, in some cases aborted hunger strike, and the consequences of living through conflict which affects educational attainment, employment as well as material factors like housing and financial concerns. By disregarding the fragile peace that the cessation of hostilities and political settlement that the Good Friday Agreement was supposed to bring, the zombie Tory government and their lackeys in Stormont will further marginalise many of these people, who already feel that the inadequate mechanisms which provide some degree of recompense and justice have been undermined.

It’s a good thing that the regressive social and cultural attitudes of the DUP have shocked so many British people, even if it shows how pitiful our collective political consciousness is when it comes to the six counties. But these attitudes and more profoundly the legal mechanisms that sustain them emerge from somewhere, namely the bitter religious sectarian rivalries that took hold in a country in which national identity was a key economic signifier over centuries of settler colonialism. As such, contending with these deeply offensive and harmful attitudes requires a struggle deeper than pushing a human rights agenda. Indeed it requires no less than a comprehensive unpicking of the history of British rule in Ireland and the role of partition. The state of Northern Ireland is less than 100 years old, and its inherent precarity is a major explanation both of the current constitutional situation and the chokehold of Ulster unionism/loyalism.

In these strange times of simultaneous stasis and fast-moving political events, I can’t help but think of Marx’s line that “the crisis is permanent, the government only provisional.” The current constitutional crisis in Northern Ireland and the situation in Westminster should be instructive for the left. It should bury the notion once and for all that the national question is no longer a factor and that the Good Friday Agreement has dealt with communal differences. Sectarianism and community division is worse than ever, and the Good Friday Agreement has simply papered over the cracks, coming to a halfway house agreement that reinforces the positions of the nationalist and unionist politicians and the reliance of the Catholic and Protestant people on them. Class politics and economic grievances pale into insignificance as fear of the other trumps the low standards of living and rising rates of unemployment. Women are betrayed by nationalist and unionist politicians alike as the fidelity of their voters remains reliant on the respective churches. Sinn Féin’s rejection of the 1967 Abortion Act based on its concern of British involvement in Ireland should be read as a misnomer, since they willingly voted for the Westminster government to administer welfare reforms in December 2015; clearly, they are more worried about their Catholic base deserting them for the SDLP. Meanwhile, the DUP’s continued role in Westminster politics denies us the Tory collapse and second election which could see a socialist leader swept to power. Whilst Britain continues its faux-neutral role in Ireland, true recourse to justice is stunted; women are still denied bodily autonomy; and right-wing extremists continue to prop up a government whose official policy powers in Northern Ireland are limited by devolution, denying all of us self-determination. It’s time for the left in this country to face up to the constitutional wreckage that is the United Kingdom, a concept on borrowed time, and took a bold stance on the national question in Ireland – Brits out.

-

Tom Nairn, The Break-Up of Britain: Crisis and Neo-Nationalism, London: Verso, 1981, p. 63. ↩