The rise of the Liberal Democrats has been a thorn in Labour's side. However, without an economic vision replacing Labour seems like a distant prospect and misses a fundamental difference between the two parties.

The Liberal Democrats at present are riding high in optimism. The mess created by Brexit has seen their support bounce and this popularity has continued despite Labour’s shift to supporting a 2nd referendum. In a hypothetical election held today they could double their vote share with Chuka Ummuna optimistically saying they could win 200 seats. Going even further, Jo Swinson says she is preparing herself to be Prime Minister.

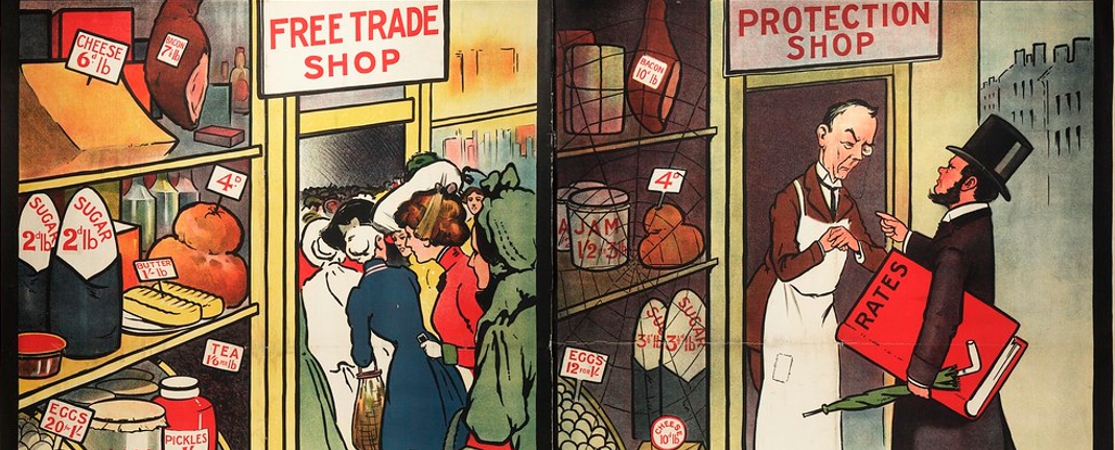

However, if the Liberal Democrats wish to win the necessary votes to enter government they are going to need an economic vision that can attract vast swathes of working-class support. Their current set of domestic policies underestimates the damage done by austerity and the policies need to improve the lives of millions of Brits living on the breadline. The millions living paycheck to paycheck can’t abandon Labour for a neo-liberal party with little to offer them other than their Brexit position.

In fact, if Boris Johnson were to pass his deal before the 31st October what would the Liberal Democrats appeal be? Either way if they want to complete their revival they will need a new economic vision.

The center left status of the Liberal Democrats in the long 90s focused on challenging authoritarian tendencies of New Labour. Economically their challenge was limited though, and they faced the same failures when faced with the economic crisis in 2008 leading to the ruinous coalition. However, with Brexit now the central issue of UK politics they found a calling representing a significant section of liberals economic, political, and social views.

Ideologically, the liberal democrats advocate change but don’t position themselves as radical. In their 2017 manifesto their economic policy calls for an economy that “works for you”. Yet it does little to work towards that by fixing the problems of austerity that the Liberals supported. While it has policies that match, and occasional surpass Labour, it has no clear vision for restructuring the economy.

They appeared embarrassingly unwilling to challenge the damage they caused while in government. On investment, they pledge additional spending on health and social care to good levels, but not to the level pledged by Labour and with no promise to fix the damage of coalition underfunding. Their education spending is drastically lower than Labour’s despite reform being a major focus of their spending plan. They continued to support Universal Credit to. Offering to end sanctions but not end the cause of dramatic increase in foodbank usage and tenancy evictions they helped create. Finally, these watered-down Labour spending proposals are made worse by their extremely regressive funding plan. They make no attempt to reverse income taxes for the richest, but instead, advocate a higher 1% tax for all to pay for additional funding requirements.

The Lib Dems proposals on tax are explicitly regressive in particular, not only will taxing working class families hurt their living standards but it will also dampen economic growth. In comparison Labour’s policy leaves the poorest with money in their pockets to spend while taxing those who on average save a great deal more and using this to invest in our public services.

They do have some policies that surpass Labour. For example reversing the reduced rate of capital gains tax that has allowed the rich to pay a much-reduced tax rate compared to those who earn via work. The low capital gains tax also creates a large loophole for exploitation. Their housing policy is also ambitious, committing to building 300k houses a year and levying up to 200% council tax on empty 2nd homes. This level of housebuilding is greater than Labour’s commitment though there is no mention of affordability’ in the Lib Dems promises.

Though in individual areas the Liberals can challenge Labour, Labour have more than headline figures to show their progressive credentials. Their radical policies offer to rebalance power in the economy. In housing the promise is not just new units but direct challenges to mechanisms which allow and support landlord power over tenants. This moves from tinkering with the market to offering real opportunities for changing how ownership works. The Liberal Democrats lack this, and no matter how large their changes they still are restricted to changing market supply and demand.

We see similar differences on Zero Hour contracts. Labour wish to scrap the practice as it is deemed exploitative. The Liberal Democrats wish establish a formal right to request a fixed contract and regulate irregular worker wages. As if companies have no power to adapt to technical changes and will freely let go of exploitative work practices that greatly enhance their profits.

Lastly, Labour’s vision includes policies that redefine the power balance in our economy as a whole. This is boosted by policies such as inclusive ownership funds, which will expand workers control accross all large firms. In contrast the Liberals reduce the structural problems of British capitalism to individual problems each needing just a technical fix. In all comparisons of Labour and the Liberals this problem is consistent, but radicalism is not an automatic path to election victory even if it is needed. The Liberals have no economic vision, but this may be enough to win substantial votes from Labour who question the feasibility of Labour’s economic vision and do not see direct benefits to themselves.

Voters who see Labour as too radical but can’t endorse the Tories may be attracted, especially if liberals up their spending more in response to recent Tory promises. But if they are serious about entering government they will need to appeal to those who care more about meeting their rent than Brexit. To do so they will need a more coherent and broader center-left economic vision, but should they develop one Labour’s answer should be more radicalism not less. Labour should think more about how they present their policies rather than the nature of them.