Here to Stay, Here to Fight is an important archive of Black British History which will be welcome and relevant today and in the years ahead.

Perhaps the group least surprised by the recent omissions from the British Academy of Film and Television Arts Awards nominations were Black artists themselves, who long have felt the difficulty of expressing a free and unalloyed artistic voice in the hegemonized space that is British culture. The dilution of Black artistic expression – the turning of patois into acceptable, consumable product for the white mass consumerist art-marketplace – is a blunting of the blade of minority expression, and what is smoothed becomes ornamental, occidental, and incidental.

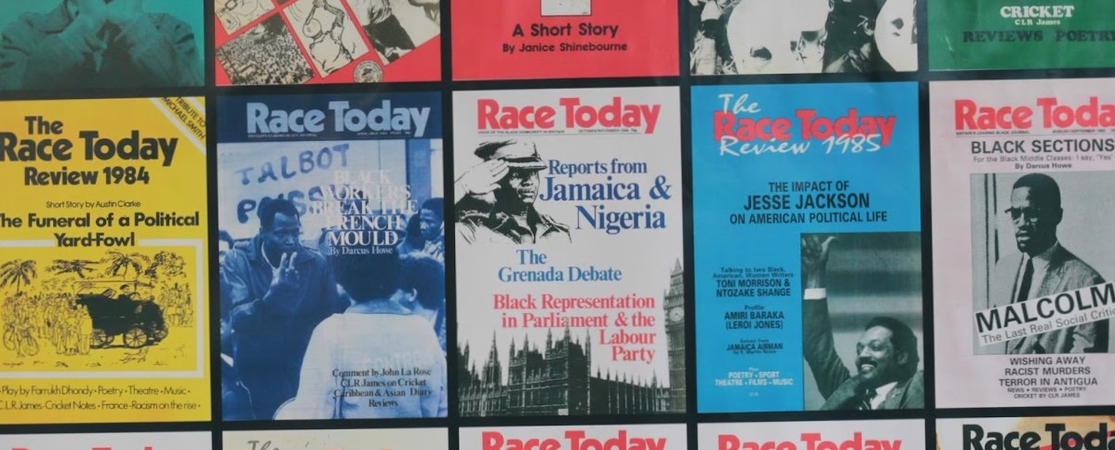

The stunting of Black and Asian artistic expression in the early 1980s is one of the many rich threads that runs through the anthology Here to Stay, Here to Fight, which catalogues articles, interviews, reviews, rally speeches and poetry from 140 issues of Race Today between 1974 - 1988. It is a dense and valuable account of modern Britain, but a flavour of which can be provided here.

Race Today was initially a monthly publication of the Institute of Race Relations (IRR), but it became autonomous under the editorship of Darcus Howe. Howe set about amplifying events on the ground and recording history as it was being made, under the banner of the Race Today Collective (RTC). As Here to Stay documents, the contributors were not trained political reporters, they were grassroots, anti-colonial, anti-imperialist activists, with shared experiences of racism. Through the RTC they sought to expose racial inequality throughout British society through their proactive campaigning and investigative journalism; and in the process they found connections with struggles in other parts of the world through their writings.

Here to Stay has eight sections covering: Race Today and British politics; Black youth; issues of sex, race and class; Asian communities; broader Black political movements; Black culture; third world liberation movements; and the legacy of Black and Asian struggles over two decades from the 1960s. Each section of the book is introduced by a different writer who was closely involved with the RTC, including Linton Kwesi Johnson, Leila Hassan and Farrukh Dhondy. It also includes contributions by the groundbreaking author of The Black Jacobins, historian C.L.R. James, who discusses Ntozake Shange, the author of For Coloured Girls (1982), and Walter Rodney, an important intellectual and political figure of his generation whose ideas continue to resonate. The arrangement of the book means you can pick it up and start at any section. For example, it ends with ‘Body Count,’ a standalone poem that could have been written for the Black Lives Matter Movement but was actually written for the 13 young black people killed in January 1981 in a house fire during a sixteenth birthday party in New Cross, South East London.

Previously under-represented in historical accounts are important sections on the prominent role played by visible minority women in diverse issues such as homelessness and squatting, and in schooling. The central chapter – and for me the fulcrum of the book – is the one on what is termed ‘(in)Justice,’ which deals with repeated police brutality, and issues of non-representation within the judicial system (a bleak picture whereby the violent and corrupt handling of Black persons at the hands of arresting police officialdom is a prelude to unjust treatment once in the criminal system). In a world of strategic ‘stop and search,’ a criminal record for any non-passivity – and all it entailed - could be easily obtained, if you were Black or Asian.

Throughout, Here to Stay shines a light on the audaciousness of the RTC, recounting their ‘fearless activism’. As is attested, they were not just militant and radical, but also pioneers who brought about broad-spectrum change around Black and Asian representation in all sectors of British life: political, culture, education, and employment. Their passion for social justice was contagious at the time as it successfully percolated down to Black and Asian youth in other parts of England who recognised in their writing the unequal treatment and/or constant experiences of racial injustices that they were experiencing and who were motivated - emboldened - to challenge the structures that oppressed them.

Enoch Powell’s ‘Rivers of Blood’ speech in 1968 left an indelible mark, casting a rhetorical stain that persists today. In Here to Stay we are reminded by Darcus Howe that “the political focus of the entire nation has been trained so mercilessly and murderously on black, that is the moment in which we live… Every single government to the present has been able to mobilize white workers on the basis of the little petty privileges that they get over Black people and stuck there – a system of colonial exploit”.

Here to Stay documents equally important moments in recent British history. Taking one example from many that could be highlighted, the book sheds light on how the 1981 Brixton Riots unfolded, detailing that the revolt against the police did not happen in isolation, or over one incident. In 1971 Joshua Francis was attacked by four policemen. Prior to this, in 1967 Brother Campbell was dragged from a Brixton bus and beaten in daylight. In November 1969 three brothers and a sister were beaten up by police at a protest. Racist attacks were not limited to one community: in 1976, a 17 year old Sikh called Gurdip Singh Jaggar was fatally stabbed on the streets of Southall; and in 1978, a Muslim called Altab Ali was killed by a white gang on the streets of the East End. The recounting goes on. The RTC ended a few years before the brutal murder of Stephen Lawrence, a watershed in modern British racial politics.

As someone who has recently written about Black Chartism, I was struck by Howe’s description of the Brixton Riots, as an “uprising [that] stands heads and shoulders above all that had gone before… Not since the insurrection of the 1830s – the Chartist movement – has English society experienced such extensive revolt. Of equal importance is the fact that the uprising represents a massive leap from the late 1960s and early 1970s when young Blacks combined under the Black Power banner to combat police violence and corruption inside the black community”.

New immigrants enjoying the benefits of upward mobility can too easily forget the giants on whose shoulders they stand. In the past it has saddened me to hear some new migrants belittle the lack of progress of Black and Asian people in professional or senior roles. There is ignorance of the experiences, struggles and history of people who came as immigrants into the hostile environment of white Britain the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s. The perception that ‘the good immigrant’ did not challenge racial inequalities and were readily accepted by the white community receives in Here to Stay a welcome correction. “Here to Stay, Here to Fight” is itself a slogan from the period, and it not only challenges any perception of meek acquiescence, it tells of the courageous confrontations and resilience of Black and Asian people who were not accepting or voiceless bystanders.

The RTC’s focus was on all discriminated ethnic communities. Thus Here to Stay highlights, for example, the historical importance of the Bradford Twelve. These were Asians who were charged with conspiracy to make petrol bombs. Serving as a catalyst for a more radical approach, pockets of London South Asian youth organised themselves as an antiracist self-defence movement. It is in the differentiation of Black British history from its better-known American counterpart that Here to Stay is most valuable. But even though the history of African-Americans was different from Britain, the Black Panther model was influential, and took root across Britain, including in areas outside the metropolis such as Cardiff. This is perhaps one of the reasons why the term ‘politically Black’ came into common usage. The congregating of Black and Asian youth under a united banner did not go unnoticed by the authorities, as there was an increase in counter-intelligence activity targeted against British Blacks and Asians, as well as the Irish in Britain.

Here to Stay also sets an array of challenges, asking, and answering: what happened to the political leadership which ought to have come from within the ranks of young Blacks and Asians? The book highlights the collapse of the Black Panther movement in Britain, advancing a powerful thesis that to ensure that another powerful organisation like Black Panther Party did not emerge in its place, the State financed a proliferation of ‘community’ projects. New community leadership roles designed to be filled in-house – to serve as a cohort of gatekeepers, by persons who “sought social elevation by way of government grants” and accolades, and whose key role was to keep everything in check for the status quo.

Here to Stay provides context for cultural change. Notting Hill Carnival is today world-renowned as a multicultural street festival celebrating Caribbean heritage, arts and culture, but in its early days it was more broadly feared as a demonstration of the Black community’s power and social capital, and this made many White people nervous. The book shares accounts from Notting Hill organisers who saw many threats by the police to remove it.

Leila Hassan’s contribution shows how Race Today remained faithful to its founding statement ‘From Victim to Protagonist’. It recorded lived experiences and provided a platform particularly for working class Black and Asian women in confronting discrimination through leading campaigns, in housing, education, in employment, and against police oppression. It took an intersectional approach, identifying how racism, sexism and class overlapped long before the term was coined. It shows what state power looks like from perspective of working Black women - especially within the NHS - and how these workers were the first to bring strike action to hospitals in Britain. It is for the reader to reflect on the centrality of Black and Asian British immigrants to the story of the jewel in the crown of post-War British social policy, the National Health Service.

Other noteworthy examples of Black and Asian female activism highlighted in the book include the Mansfield Hosiery Mill strike in Loughborough in 1972; the Imperial Typewriters factory strike in Leicester in 1974; and the two-year industrial dispute at Grunwick Film Processing Laboratories, in Willesden, against discriminatory practices in 1976. The book also shows that immigrant workers were not just fighting management, but also the trade unions, which often refused to support them, and in a number of cases actively opposed collective action taken by immigrants.

Noting its pan-England accounts, my only critique of the book is its emphasis in a British context on England, lacking examples from Wales for example, where there was also a Black Panther movement. There is, too, an absence of Black and Asian LGBT and disabled people. This might reflect the times being written about, or perhaps there will be a follow-up?

Regardless, the impact of the RTC recorded in Here to Stay cannot be underestimated. They were instrumental in the strategic, self-organisation of the new communities of Britain and tapped into the consciousness of Black and Asian Britons like nothing before. Immigrant experiences and their historical accounts could easily have been ‘whitewashed’ from history (suffering the fate of the generation before, of Black and Asian people in the World Wars): something tells me the RTC knew this, hence the reason they became recorders of their own His/Her-Stories, to preserve these for future generations. Here to Stay, Here to Fight pays tribute to the youth who took to the streets, the generations of Black and Asian men and women who fought for equal rights to employment, education and housing, and the victims of racism and their bereaved families that took to the courts and challenged structural and institutional racism of that time (and today). It is to be wondered that, despite this rich narrative of Black and Asian people mobilising in Britain, we too often look instead at injustices in other parts of the world that resonate with us, for example, people will know about the Montgomery Bus Boycott in Alabama, but not about the Bristol Bus Boycott.

Here to Stay, Here to Fight is an important archive of Black British History, welcome and relevant today. Much of what is unfolding around us in Britain can be traced to the recent past: the Grenfell Tower Fire; the Windrush Scandal; anti-Muslim sentiment; the Black Lives Matter movement; the police shooting of Mark Duggan; an increasingly hostile environment. Academic, but approachable, this book is a beacon for anyone interested in race in Britain. It is also a gift to young and old radicals to ignite or reignite that fire which characterised the Race Today Collective, especially in what may be bleak years ahead.

Here to Stay, Here to Fight: A Race Today Anthology is edited by Paul Field, Robin Bunce, Leila Hassan, Margaret Peacock and published by Pluto Press