Radical music, like radical politics, can energise and mobilise us towards collective liberation—but physical and conceptual borders are threatening this potential.

With music’s mass commercialisation—siphoned through the haze of online algorithms, ephemeral online marketing and hyper-corporate live music events—it’s easy to forget its potential as an alternative form of language. A catalyst for bringing people together. A space where people can share analogies. A binding agent for bodies to build collective strength; the groundwork for resistance. We must never forget this potential, and we must stop borders from restricting and repressing it.

In Amiri Baraka’s ‘Blues People’, he tracks the everyday “functionality” of West African music culture. Using voices, polyrhythmic drumming and varied instrumentation, music was a source of communication; courting and challenge between bodies; an activity for workers as they carried out daily tasks; ritual connection in and between communities. In Europe, outside the authoritative milieu of courts, there were farmer songs, sea-shanties, mountain songs, tales of struggle and the power of people coming together. One of the most radical and giddy tales, ‘The Cutty Wren’ (considered by many as one of the first English folk songs) locates itself around the time of the Peasant’ Revolt (1381), a struggle associated with the introduction of an excessive and repressive poll tax. The song tells the tale of a mercenary police force (the Cutty Wren), whom the peasants fought, killed, and eventually ate for dinner.

The past can teach us a lot about the human and interconnective potential of music, but this is something that still occurs today. In my adopted hometown of Turnpike Lane, London, music is everywhere. If I open my window, I can hear my neighbours meeting up for joints, beer, and pizza, toasting over homemade beats. Two minutes up the road from my flat, a mosque. If you walk a down the road a little, you can hear their collective prayers mix with high-energy folk jigs from the speakers of a Greek bakery. Outside, locals hang out and sip their espressos. As cars swing by blasting bass out of their modified soundsystems, kids walk down the street sharing grime and drill raps. The dizzying swirl of sounds brings me to life. As I write this and look out to the gigantic new-build complex erected beside Hornsey train station, I hope that the magic never ends.

To emphasise the importance and potential of music, it is worthwhile considering Sara Ahmed’s description of communities as bodies.1 Like communities, bodies are ecosystems collated by an infinitely complex set of inner subjectivities—skin, blood and bone. They have nervous systems that rely on nurture, connection, and understanding. In this metaphor, music holds the potential to be a binding agent between organs. It can be the pump to make blood flow —the surge to make bodies come to life.

I co-curate a music festival in Glasgow called Counterflows that takes this elastic definition of the body as a starting point. Over four days, we bring to life a temporal space where radical and vital voices from around the world can disseminate, coalesce and find potential common ground. There’s no headline acts and (hopefully) as few hierarchies as possible; people of different ages, genders, race and physical abilities can join in the fun. This year we hosted Brazilian Baile-funk queen MC Carol, one of the leading voices from the favela community, spitting urgent spite against racism, misogyny, and Brazil’s ever-increasing structural oppressions. There was broken projected yodelling; Guarapo—a new form of dance music from Baranquilla, on Colombia’s Caribbean coast; transatlantic free-jazz collaborations; music played by a community initiative youth brass band; cross-art-form projects; film screenings, and more. If the festival is itself a body and the artists are its inner organs, then the topography of it is a map of Glasgow. The festival moves from one community space to another. Audiences, artists, and festival workers share the same experiences: they hang out together; they dance together; they eat together. Counterflows is a drop in the ocean, one of many organisations encouraging an open, international and a pluralistic dialogue within the arts. But the potential to nurture a shared space where, as artists and audiences, we can feel deeply connected and deeply alive—where people and their lives are more than mere commodities—feels more important than ever.

There were two key parts missing from the festival this year though, and both were lost at the hands of the UK Border Agency. The Ghana Footsteps—a new project exploring volta rhythms, involving musicians from Taafi in Ghana in collaboration with local DIY musicians from Glasgow—and Mohammad Reza Mortazavi—a percussionist who radically expands the language of the Iranian toumbak —were both unable to enter the UK. The former was due to a straight-up visa rejection; the latter due to a week-long delay in his ‘fast track’ visa rejection—long enough to make him miss two flights to the festival, stuck, with no passport, at the Iranian embassy in Berlin. These decisions left artists and audiences devastated. We (the organisers) were devastated too, but also deeply embarrassed for getting people’s hopes up and wasting so much of their time. The decisions cast a bleak shadow over the festival proceedings. Many cried during the Ghana Footsteps film. Thanks must go to Arash Moradi and Michael LaCour, the artists who generously stepped in at the last minute to deliver brilliant replacement performances.

Visa rejections and delays are nothing new in the UK. Last year, the Guardian published a piece on how the UKBA’s decisions are affecting the UK music economy and ecosystems. The piece highlights the shared collective disappointment and infuriation at the UK Border Agency’s application process, communication process, and decisions. One of the most shocking accounts came from Ben Makkes, manager for legendary Ghanian highlife artist Ebo Taylor, who was refused entry despite having previously entered the UK to perform countless times during his 60 year career. “In the end,” Makkes said, “we lost €20,000 (£17,000) in flights and fees, and I don’t think we’ll come back to the UK because of that.” I have lost count of the number of artists I’ve worked with who have said the exact same thing to me. And the doubt and anxiety is rising even beyond artists whose nationalities mean that they cannot enter the UK without a visa. With the uncertainty surrounding Brexit and the looming potential of closed borders, many European-based artists have started expressing concern over future UK performances.

If one needs a visa to enter the UK, the application processes are costly, rigorous, and often confusing. The Tier 5—Creative and Sporting Visa application makes several intrusive and exclusionary demands, including enquiries into artist bank balances. Musicians are required to provide bank statements covering 90 days, to show they have had at least £945 in savings continuously for the entire period. This isn’t just a racist and classist demand. In Ghana, where many people do not have bank accounts, this instantly renders the application process near impossible. On top of this, many artists in Ghana do not carry photo-ID or have registered home addresses, meaning the amount of pre-visa application work can take months. It is worth noting that there is no remuneration or insurance system for a failed or delayed visa application. We were extremely luckily that the British Council, who were funding the Ghana Footsteps performance, permitted us to reallocate that funding. This allowed Ghana to make a short film that was screened at the festival, and offer a series of drum workshops in Taafi. If we hadn’t been that fortunate, all the work and costs involved outside of paying for the visa applications—gathering paperwork, project administration, preparing music, rehearsing, travelling to and from embassies— would have been lost to the ether.

Once visa applications are submitted, there is no way of speeding up the process, or checking on its the progress beyond the categories “yet to be processed”, “in process”, “failed”, or “accepted”. If you contact UKBA, the call will cost £1.37 per minute on top of standard network charges, with waiting times often lasting hours. Email enquiries cost £5.48. The process recalls a similar system introduced in prisons in Jersey and Guernsey, where families have to pay £10 to use an encrypted video call service if they wish to contact their incarcerated loved ones. Othered, colonised bodies are capitalised upon by the colonial state: the same state that incarcerates or rejects them.

The effect of these visa failures is more than a missed opportunity for paid work and new audiences for artists. It’s also more than the loss of the obvious cultural and economic benefits for the UK. Last year, Counterflows hosted the debut UK appearance by Bamba Pana & Makaveli (Sounds of Sisso) from Uganda—a two-piece who are part of a revolutionary new sound from the Singeli region. Together, they make raw, fast, and polyrhythmic dance music, influenced by the likes of Zanzibar Tarab music and South African afro-house. After their soaring performance at Counterflows, they hung out for a few days in Glasgow and collaborated with some local musicians. Their label manager Ario (who co-runs Nyege Tapes) kindly invited some of the Glasgow musicians (Laurie and Richard from The Modern Institute) out to Uganda to continue the musical dialogue at their artist residency programme and community studios. They were also invited to play at the label’s Nyege Nyege Festival, an inclusive international festival that has been heralded for its support of both radical new African music and local LBGTQ+ communities. Other UK-based musicians joined in the dialogue too, including London-based afro-futurist artist Nkisi and experimental dance artist Rian Treanor, who worked on a project with Acholi fiddle player Ocen James. Bamba Pana & Makaveli have since been back to the UK a few times, sharing their music with new audiences, and opening the dialogue even further. Despite the infinitely complex colonial and historical ties between Uganda and the UK, and the inevitability of the music entering into a profoundly unequal international economy, the seeds for a positive internationalist solidarity can be sown. When artists are granted access to move between countries, we can use these seeds to grow a new set of roots. A new strength to hold us together.

Part of the reason Counterflows exists is to challenge experimental music’s predominately white, US/Euro-centric, and institutional history. To bring its inert hierarchies and dogmas to trial. To kick-start an expanded and inclusive dialogue concerning what radical new music is. Where does this music come from? How does it come into being? How does it flourish? There are manifold definitions of experimental music (and its close semantic partner “avant-garde music”), but the term usually refers to the pushing of stylistic and genre definition. This includes a variety of techniques, including the likes of indeterminacy (where parts of a musical work are left open to chance or the spontanous choice of a particularly interpreter), musique concrète (where recorded sounds are used as raw material and often modified by the application of tape manipulation and audio effects), and free improvisation (where musicians create improvised music beyond apparent logic or pre-prescribed inclination).

While experimental music’s legacy has expanded and evolved over the decades, it risks, through its own inertia, becoming rigid and uniform. Let’s consider briefly Pierre Schaefrer’s radical proposition for a reduced listening, an ideology at the heart of musique concrète. Partially a result of the introduction of tape recorders—and with it the ability to listen closer than ever before—Schaeffer famously said that all sound could be considered music. This is in itself a radical, internationalist, and almost utopian proposition. One that could emancipate all forms of music from vague genre tropes or geographical barriers. So why, then, has contemporary musique concrète become a largely academic, Euro-centric and elitist enunciation? Or, to put it bluntly, a bunch of (mainly) dudes with gigantic, expensive synths?

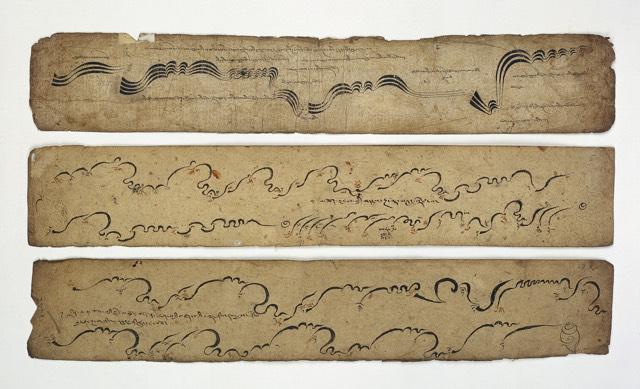

If Western experimental music ideology has emancipated itself, deconstructed itself, and “experimented” on itself, then it has only done so from within itself, and its own history. A history steeped in and predicated on the classical 12 tone harmonic scale. For all the objective “truths” and “potentials” that this music claims to offer by performatively departing from this structure, one is left with an awkward question: what about music and cultures that didn’t lean on the Western 12 tone scale in the first place? What, for example, about the stunning 19th Tibetan music scores, which closely resemble the sort of graphic notation associated with the likes of Cage, Cardew, Feldman, and Stockhausen? What about African artists who invented their own instruments and notational musical systems? What is an inherently more “experimental music”: one that emancipates itself from its own historical forms and yet continues to riff off them? Or one that creates, entirely, its own language, its own system of being?

In the history of experimental music’s sibling “minimal music” (or, as Jennifer Lucy Allen calls it, “menimalism”), why are Hindustani classical music and South Indian Carnatic music deserving of little more than a footnote? Why was a radical artist like the gay black musician Julius Eastman largely ignored and marginalised until decades after his untimely death, homeless and alone? (Check out Eastman’s Femenine here.) But Western experimental music has always taken this patrician attitude: extracting labour and “inspiration” from othered bodies whilst doing nothing to challenge (and often actively upholding) the violent, imperialist processes of global white supremacy.

In his essential text A Power Stronger Than Itself: The Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians2, George Lewis recalls an unrecorded session that took place in 1965 at the Harper Theatre in Hyde Park, Chicago. Organised by the ‘Contemporary Music Society’, the session featured [Joseph Jarman—composer, poet and member of the legendary Art Ensemble of Chicago, who would become one of the most important figures in the black radical tradition—in collaboration with a group of university students and composer-performer John Cage. Lewis later interviewed Jarman about this collaboration, and the contrast between Jarman’s account (“[Cage] just said… ‘Do as you feel.’And… I just started playing, and moved all over”)3 and Cage’s own account of the collaboration is illustrative. Lewis writes:

Cage framed himself as something of a teacher for a group of unnamed “black musicians”. Moreover, despite his professed lack of interest in improvisation (reiterated later in the interview), Cage somehow managed to find ways to critique the musicians’ performance practice – at their request. “And I said to them that one of the troubles was that when they got loud. And they said, ‘How could we change that? They were willing to change”. While one could well imagine that the AACM musicians were open to learning from Cage, the notion that these musicians would have learned about space and silence from him is at variance with the recorded evidence of AACM improvisations from the period. Moreover, as Cage scholar Rebecca Y. Kim has noted in an unpublished paper, the program notes for the Cage-Jarman event employed “a language of historical synchronicity, identifying two parallel movements in new music”—hardly an attitude that one might attribute to a mentor-student relationship… The Down Beat review, which had no particular criticism of Cage’s work per se, criticised Jarman and his musicians for their supposed failure to respond to Cage’s sound.4

Cage was one of the leading figures in experimental music, and one of its key ideologues. That both he and the contemporary media chose to both strip Jarman of his agency and critique his group in such an ignorant, self-aggrandising manner serves to accentuate the elitist, racist histories of experimental music, and its lack of engagement with other ground-breaking marginal musics. In Cage’s famous Experimental Music—presented as a statement/lecture to the Music Teachers Association in Chicago in 1957—he suggests that experimental music should not be “an attempt to bring order out of chaos nor to suggest improvements in creation, but simply a way of waking up to the very life we’re living”. Considering this anti-purist call to arms—a cry for greater human understanding through experimental music—why is his philosophy not followed through in practice? Moreover, when we consider that much of Cage’s philosophy and musical output is based upon readings of Indian and Zen Buddhist philosophy (and that other white experimental musicians extract similar inspiration from other Majority World cultures), surely the inclusion of non-white, non-Western voices would represent the smallest form of symbolic remuneration? It’s the least they could do. And given the advent of the internet—and with it more shared knowledge than ever before of marginalised bodies, cultures and musics—all of us in the larger music community must use this information to dissect and challenge these histories. There’s really no excuse.

But all this discussion about what is or isn’t ‘experimental music’ (and whether the term matters in the first place) risks overlooking the fact that artists collectively build their own traditions. They form their own styles, their own genres, and their own ways of being. They don’t need Western institutions to crystallise their music, justify it, or make it their ontological property. Some musical cultures prefer to remain untouched. Some want to meet and share and co-create—but as equals and as agents, not as objects, or property, or curiosities. The frustration lies in realising that, despite how vital, how radical and how world-shaking these voices are, their histories have been largely ignored or rejected by the West’s physical and conceptual borders.

A few weeks ago, Red Bull Music Academy—an international platform for manifold underground musics, ironically funded by a CEO who would far prefer to see bodies torn apart than brought together—ceased operations. As its sizeable archive lies dormant (and with no news on who or what will guarantee its future existence), many are questioning how esoteric music communities can survive in a shallow economy. The conversation is vital, especially given the increasing lack of support of the arts under austerity. But beyond RBMA’s high-sheen corporate window shopping—where marginalised bodies and their stories are served up to help sell chemical-laden slurp—we must never forget the radical potential of music. Similar to the ways in which grassroots politics can energise and mobilise rejected bodies towards liberation, music can build communities, sow the seeds for collective strength, and build resistance. It is an international, polymorphous, and polyamorous phenomenon. It is a power that we must treasure, and one that we must let flourish without divisions, hierarchies or borders.