Keir Starmer's leadership bid gestures towards generosity whilst manipulating our emotions & appealing to our unconscious biases. We should refuse this dishonesty.

Keir Starmer sent me an email.

Picture it. It’s 2024 - the day of the next general election. You’ve just finished your final door knocking round and you pile into the committee room. The exit poll flashes up on the TV and we’ve just elected the first Labour Government in twenty years. No more broken Tory promises, no more Boris Johnson, no more divisive Conservative government.

I couldn’t do as I was told. Like, perhaps, many of us, I struggle to imagine my life in a year’s time, let alone four or five. Where will I be living? What will I be doing? Will I still be alive? It’s hard to predict. Instead, my mind flashed back: back to that moment on the night of the 2019 election when, exhausted, hungry, my clothes soaked, I walked through the door and saw the exit polls. We threw everything at it, and it wasn’t enough, or the timing was wrong, or people chose cruelty. The world seemed slippery somehow, and distant—no longer able to hold me. The talking heads on television cackled and smacked their lips in glee, savouring the moment of their very impartial victory. Savouring the moment of our defeat: we the lowly, who only wanted to live, to know what it might mean to truly live. Despite myself, despite all of my commitments, that moment felt like an extinguishing.

When I read what Starmer (or his “team”) had written, my mind flashed back to that moment. Not forward to the rosy future that he conjures—but back to that moment of loss, of disappointment, of hopelessness and helplessness. And that is precisely what those words were intended to do. For what Starmer is selling is not a set of policies, or a path to mutual empowerment and collective liberation. The few policies he’s offered would make life actively worse for many, as David Wearing has repeatedly observed. There’s no suggestion of the kind of deep transformation of the social order that is necessary for us all to flourish.

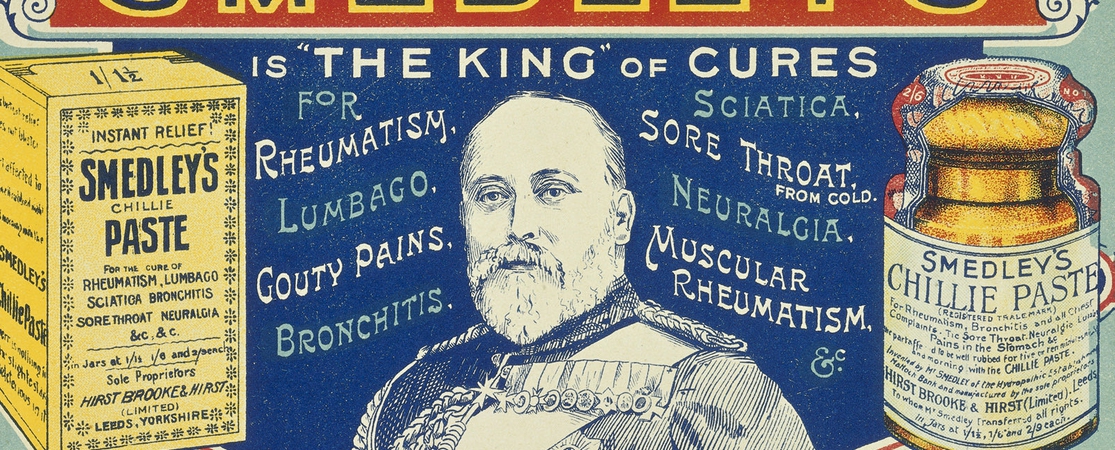

No: what Starmer is selling is a false promise, a quackish cure-all. Dr Starmer’s Patented Electability Elixir. What he’s selling is the promise that what happened in December will never happen again. Appealing directly to our broken hearts, he offers us the end of pain, the end of risk—and, ultimately, the end of politics. If Starmer offers hope, it is the hope of the headmaster—kindly, but authoritarian—who says, “well, next time you will behave yourself, won’t you? And then you won’t need to be punished.” The affect is paternal: let the adults take care of this. His promises thus conceal a disciplinary intent: you can have peace, unity, power (of a sort)—but first, you have to put down those silly principles and be sensible.

But, even if this was likely to work on its own terms (of which more later), why should we? The call to be sensible, to be realistic, is at its heart a call for us to resign ourselves to the state of things. Gaston Bachelard once observed, commenting on Nietzsche, that “there is always a little naïveté in the will to power.” The futurity of this hope, he said, is

to dream of power beyond actual power. Without this dreamt horizon, the will to power would be powerless.1

Similarly, Derrida has noted the crucial role of impossibility for any radical project. “If the structure of the field,” he says (the field in this case is politics):

makes an invention possible… then this invention is not an invention. Precisely because it’s possible. It merely develops and unfolds a possibility, a potentiality that is already present.. For there to be an invention… the invention must appear impossible. What was not possible becomes possible. In other words, the only invention possible is the invention of the impossible.2

That is to say, the very notion of possibility requires that we imagine what is impossible, and aim for it. To think beyond actually-existing power, to think towards that dream-horizon where things might happen, things might change. If the structure of politics makes our demands, our hopes, our lives impossible, the answer is not—can never be—to amend those hopes, to shrink ourselves down into a size and shape that the present system can accommodate. That Starmer knows how to inhabit this structure, that he is at ease in this system that was made for people just like him, may seem a comfort to those of us who feel beaten-down and desolate over what happened in December. Imagine, an experienced hand at the tiller, guiding us expertly through the storm. But this promised panacea, this elixir, is poisonous. To smoothly and uncritically inhabit a system is to perpetuate it; and it is the system that’s at fault, the system that must be challenged.

We will need to do this whatever happens: as I’ve written elsewhere, Parliamentary politics must be reckoned with, but “should never be the limit of our politics, never the sole ground which is being contested.” There is no perfect candidate—and nor should there be. It’s notable, however, that where Rebecca Long-Bailey has named and rejected the “London-centric gentleman’s club” configuration of political power, Starmer has merely promised to wield that power in our favour, “forensically”. The word forensic is derived from the Latin fōrensis, meaning ‘of the forum’; i.e. of, or taking place in, the public sphere. But the current government have demonstrated that they couldn’t care less for the public sphere (and besides, they own or are mates with most of it anyway). A public holding-to-account only works when both parties agree that the public matters: when there is some threat of shame or loss, and where the balance of power is in the favour of the person demanding accountability. In this instance—unlike in court—the party Starmer intends to cross-examine holds all the cards. The party also, demonstrably, has no shame, and there is no presiding judge to whom one might appeal. What good will his “forensic” questions do?

This isn’t the only area where actually-existing Starmer falls short of Long-Bailey. Where Starmer pledges to “put the Green New Deal at the heart of everything we do”, Long-Bailey is calling for a full-scale Green Industrial Revolution—one of the last manifesto’s flagship policies, and one of its most radical, which Long-Bailey devised herself, in careful collaboration with trade unions and climate activists. Where Starmer panders to an increasingly vocal minority of transphobic bigots by refusing to sign the pledges offered by the Labour Campaign for Trans Rights, Long-Bailey supports self-ID and the rights of trans women to access crucial services. Where Starmer makes vague noises about pluralism whilst being backed by a coalition of weirdo right-wing Blairo-revanchists and the dregs of Brownism (Progress’s Jenny Chapman and Labour First’s Matt Pound are both involved in his campaign), Long-Bailey unashamedly calls herself a socialist.3

Moreover, for all his trumpeting of the word, Starmer is demonstrably not the ‘forensic’ candidate. His promotional materials offer little in the way of substance: he appeals to our emotions, our broken hearts, our unconscious biases: how we imagine ‘competence’ should look. He wilfully deploys certain affective strategies in order to conceal the apparent fact that he has nothing to say. And while I truly believe that our emotions are political, are sites of struggle—that, in many ways, we need to be far less forensic and far more engaged in affective work (what Larne Abse Gogarty and Hannah Proctor have called “revolutionary tenderness”)—this is not the way to go about it. This is work that needs to be done honestly and transparently, and with the most careful attention to ethics. Otherwise, it’s just advertising; just more manipulation. More false promises.

There’s no doubt that defending and extending a socialist position will be hard. (We call it “the struggle” for a reason!) It will require levels of engagement, commitment, and collective resilience that a more conformist route will not. There will be no easy victories; but the point is that the struggle itself is worth it, the commitment is worth it—to fight for transformation, as Tom Gann has said, transforms us, too. What’s the point in winning just to win? What’s the point in winning just to feel, for a change, our boot on their necks? If the kind of power we imagine and struggle towards does not move us beyond the actually-existing configuration of power, what sort of movement can we claim to be?

There will be no easy victories under Starmer, either. The thing is that the only way to really capitulate to bullies is to agree to do their dirty work for them. You can beg and beg your mum for expensive trainers, and then discover you picked the ‘wrong’ kind. Or you can adopt all the ‘right’ opinions, but then there’ll be some other reason to single you out for ridicule. The only way to make them stop is to join them in hurting somebody else—and even then, it’s not a guarantee. We see this dynamic playing out at so many levels of our society right now—take, as an example, the way trans people or migrants are posited as ultimate enemies, the intention being to create what Tom Gann has called “a cross-class coalition of whiteness” [and/or cis-ness]—and we cannot forensically reason our way out of it. If anybody thinks that a socialist politic would be more possible if only we adopted the bland, professional stylings of the centre-right, they’re sorely mistaken. There are a whole set of forces and interests, their roots centuries-deep, who would do anything to cling to their stolen land, wealth, and power. There are a whole set of forces in and around the Parliamentary Labour Party who will not countenance another five years of being led by the left of the PLP, let alone the membership. Some of them are involved in Starmer’s campaign. Moreover, these forces have access to a media apparatus that, as we have seen, will take great pleasure in vituperating even the mildest of left-wing proposals. There’s no appeasing them: with the logic of the bully, you will either join them, or they will beat you. Keir Starmer cannot and will not protect us from this. We have to protect ourselves, protect one another, and use all means at our disposal to fight for our lives.

So when I read Starmer’s email—when, as intended, I am manipulated into reliving that night in mid-December when things seemed to go dark—I think about all this. I think about the precious lives lost to austerity, police violence, war. I think about the people I met when canvassing, who over and again would say, “we’re doing this for Jeremy. He gives us hope.” I think about my aching limbs, my numbed and soaking feet, and the feeling as the exit poll came in that it was all for nothing. And then I feel proud. We campaigned hard for a manifesto we truly believed in. We were lights in the darkness for one another. We dreamt that impossible horizon, and we built bonds of love and commitment that will carry us there, if we’ll let them. And we deserve all of that again, and more. Would I be proud to campaign for a Keir Starmer manifesto? I don’t know, but it’s difficult to imagine. Perhaps the real question is this: would Keir Starmer and his right-wing backers be proud to stand alongside us on the picket line, outside the detention centre, at the airport blockade? Would they walk with us, or at least clear our way, towards that (im)possible revolutionary horizon? Or, as I suspect, is their vaunted miracle cure in fact something bitter and deadly—a punishment for our disobedient transgressions?

-

Gaston Bachelard. 1942. L’eau et les rêves: Essai sur l’imagination de la matière. Paris: Librairie José Corti. p.241. (My translation.) ↩

-

Jacques Derrida. (2003)2007. ‘A Certain Impossible Possibility of Saying the Event’. In Critical Inquiry 33:441-61. pp.450-1. ↩

-

Unless otherwise linked, all my information about the candidates’ policies is drawn from their respective manifestos: Starmer; Long-Bailey. ↩