The economy is already planned, the task is for that planning to be based on democratic & ecosocialist values not profit.

Economic planning is a daunting topic. The collapse of socialism as a powerful global movement largely killed the dream of a planned and democratic economy as part of the public imagination. This old idea did not die though. The pandemonium of climate change now looms above all economic and political discussion, a new spectre haunting the fantastical realities of liberal democracy in the 21st century. Totally unprepared to deal with the hard realities of ecological destruction, the negotiating process begins - a barter with Nature. We agree to unenforceable international accords, we subsidise and adjust until the numbers point in the general direction of progress, but definitive action seems to evade international leaders. Why? Surely somewhere in the collective economic power of these multi-trillion dollar economies there is a way to force the hand of smaller economic agents towards the goals established by their own governments.

There is a reason this does not happen: all economies are planned - we just happen to live in an economy planned almost exclusively around profit. Every economic decision taken in the modern economy, from bloated defence budgets to investment in industrial automation, all occurs due to the chaotic economic plan fought out between capitalists in the mythical free market. The market is free because it plays within the rules as planned. Maximising production and minimising competition are just components of a broader goal: generation of profit. Restrictions on the economy through regulations, external sanctions, even climate change, do not change the rules by which our economy is planned, they only change the strategies which allow for profit to be made. Our method of planning has produced a grossly distorted economic landscape. The incentives of the market economy are so disconnected from the fundamental forces of production that drive it that it is unable to plan for a structural shock like the one promised by climate change.

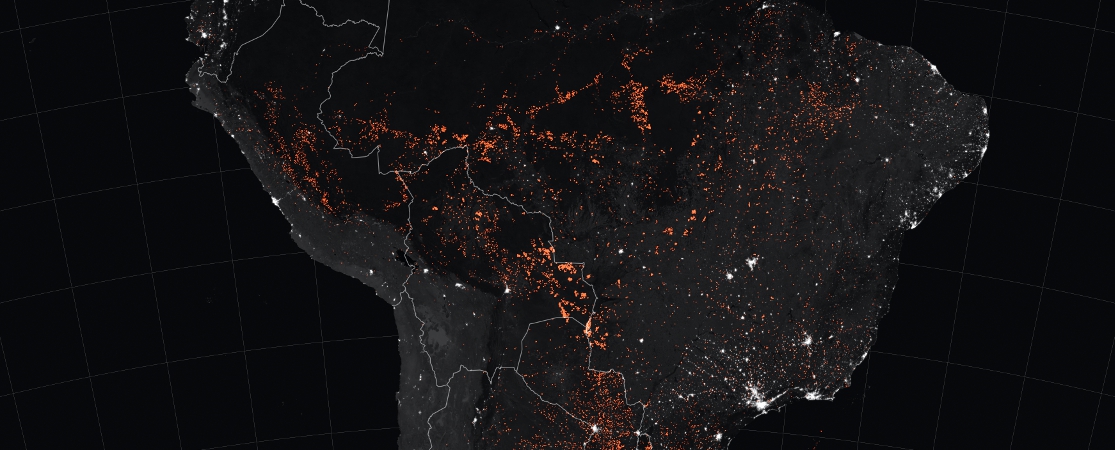

The central failing of economies planned to generate profit is in their total lack of accountability with overarching uncontrolled power unrestrained by representative forces. No democratic body, from the state to local citizens’ councils are given a voice in the room. The sole legal requirement, what publicly held economic agents are required to do, is to ensure that profit is produced. All other voices are externalities to be managed. This drive towards profitability can create competing goals for firms, putting them under pressure from the government or their investors to change their behavior, but this form of control has significant limitations. This “pressure” rarely takes the form of action, and almost never has actual consequences that impact the functioning of the company or its profitable status taken to be the sole form in which human production can be organised. Even in non-traditionally funded corporations, such as those in the tech industry, the flow of capital is only changed by how long investors are willing to wait for profit. The multitude of nudges and even rewards offered by regulators to encourage changes of behaviour has, under neoliberal conceptions of the inviolable market, given a wide berth to companies to externalise regulation as an operational cost. The form of economic planning incorporates this and will, from time to time, make changes, but there is little reason to believe that hard limits to what profit can and cannot correct for can be introduced through regulatory methods. Climate change is a perfect example of an area where plans-for-profit come undone. The wholesale destruction caused by climate change dissects the chains of supply and infrastructure not only in the brief shocks of more powerful disasters, but also in the slow creep of trends that delay planting seasons, lower yields and make scarce the essentials of life in large regions. Planning for profit would dictate abandoning, not deepening, investments in affected areas.

Research indicates we have passed important thresholds that have made it very difficult to change course from a worst case scenario for climate change. Some radical right-wing theorists believe that the market, realising the terrible mistake it has made, will correct itself and attempt to undo the damage of climate change. This is particularly dangerous, especially when we look back on a century of capitalism’s response to crisis: internationally, imperialist scrambles for resources, and domestically, fascist internal control of the engines of profit. Through violence, capital will attempt to undo the symptoms of climate change, as they affect the already powerful and well-to-do, rather than accept the impossibility of the massive levels of overproduction. Profitability, which drives virtually all industrial and agricultural factors related to climate change, is clearly at fault, but even those on the right with less ideological commitment believe it can be corrected through similar market incentives.

Industrial development, however, is inflexible and often relatively fixed geographically. The development of one kind of infrastructure, say where electricity is generated and how it is distributed, necessitates a particular course be followed for future infrastructural developments. We are very far down the line in how we produce, and in what manner we distribute, energy - changing course entirely would be unbelievably expensive, as it would require development of infrastructure from the ground up. We do not have a subsidy that can push in that direction. We also have less 15 years to do this.

Democratic Planning and Degrowth

There is a general reticence to discuss socially planned economies among the democratic left, largely due to the negative associations of Soviet-type planning. Our current economic plan, “how to squeeze profit from everyone and everything,” is insufficient to address the exigent, existential threat posed by climate in the 21st century. Economic planning intervenes in the cycles of consumption, development, and production and if we are serious about ending ecological damage can kill growth. Both putting more people to work more intensely usually wastes more, currently unpaid for, ecological resources as does making people work for longer. This is very unpopular with industries trained to instinctively seek both profit and growth, and potentially difficult to sell to consumers. If we do not accept the need for both planning and degrowth, however, it will not matter how we sell this, because we will probably be dead.

Economic planning is therefore possible. However, it is not enough to simply plan the economy. We cannot rearrange deck chairs on a sinking ship. We must actively lessen the burden on infrastructures of production and distribution to cut back investment and production where capitalist excess has bloated. This is called “degrowth,” and is sometimes invoked in rebuttal to economic planning, as an argument against centralised planning, rejecting the spectre of 20th century Soviet planning. This sometimes manifests itself as a “red-green split” politically, where the goals of socialist governance come to be at odds with ecological concerns. However, degrowth necessitates economic planning in order to function at the scale proposed by the majority of its proponents, especially given the global character of the present economic system.

We see half-hearted gestures towards this kind of policy in the mindless, moralistic efforts of liberal-democratic powers today. Bans on single-use straws and plastic bags treat these products as a vector, suggesting that reducing particular avenues of waste and overproduction will solve a broader problem. The development of throwaway culture in the 20th century created these intentionally wasteful products, but banning them in a patchwork does not meaningfully address the broad issue of over-production of plastics in consumer goods in a vast number of industries and products.

Degrowth is a way of addressing the present day crisis of overproduction, in the same way that early Soviet industrial policies were a way of addressing a crisis of underproduction. Both crises claimed lives and both required massive and decisive intervention to prevent. For the Soviets, their crisis was answered in part by the GOELRO plan, the precursor to the five-year plans, which defined their answer explicitly: Communism is Soviet government plus the electrification of the whole country. Today, we do not need to manage the carcass of Imperial Russia, but have a dysfunctional economy of our own. We overproduce consumer goods, we waste billions of tonnes of food, we subsidise unsustainable agriculture, keeping a bloated old system on life support far beyond what the Soviets were capable of sustaining. Our “green revolution” has lead to the breakdown of natural systems that cycle nitrogen, phosphorus, and carbon, creating the potential for uncontrolled collapse of many natural systems. In the “The Critique of the Gotha Programme”, Marx observes that:

Labor is not the source of all wealth. Nature is just as much the source of use values (and it is surely of such that material wealth consists!) as labor, which itself is only the manifestation of a force of nature, human labor power. the above phrase is to be found in all children’s primers and is correct insofar as it is implied that labor is performed with the appurtenant subjects and instruments.

We live in a rare era, ecologically speaking. The infrastructure that undergirds all societies, and indeed our species itself, developed in an interglacial period of relative climatic stability. The transition we are forcing threatens the source of material wealth. The profit motive encourages risky decision making and extension of the supply chains and productive centres that have enabled the highly and narrowly focused efficiency of various players in the modern market. But that risky decision making is not operating on its own. Who decides where risk is allocated? Who receives the burden of those risks? These are questions asked and answered by the property-owning class, not by the working class. They allocate risk to places they do not live in and places they consider of less importance. The mechanisms for allocating this risk take many forms. Globally, it is imperialism and colonialism - putting jobs and waste in far-away places to prevent disturbances like labor unrest at home. Domestically, it is redlining, deindustrialisation, and regional control of resources - pipelines running through reservations, waste dumped in poor communities. In sum, the consequences of allowing property-owners to plan the allocation of risk is the primary cause of climate change. Without powerful business interests funding three decades of propaganda against climate science, without corporate control over foreign policy to maintain a stable flow of Empire’s most necessary fuel, climate change could, perhaps, have been solved slowly, gradually, with small concessions of daily comforts to keep atmospheric carbon at a minimum. Instead, the bourgeoise and its allies have planned our future for us, and it is grim.

Subsequently democratic planning, in the traditional sense, is preferable and can build for a consensus on degrowth and a model which can achieve it. How would we, in a planned economy, allocate these risks, while maintaining the world’s complex economy? Surely in our modern global economy, it would be more difficult to manage the diverse range of inputs and outputs needed? Democratic planning may be able to surpass market profit-seeking organisation of our productive capacities in ensuring not only uninterrupted production of essential economic goods, but more crucially, the fair distribution of risks and benefits. To assess this, we must look towards the already existing systems that help structure our global economy, find the most useful tools, the leanest, most capable solution, and discard the burdens of profit and the profiting class.

Tools for Change

The tools to achieve some form of planning are already here. Economic planners should drool over the complexity and elegance of infrastructure that allowed Wal-Mart, an infamously wretched employer whose labour practices have been regularly criticized, operate the some of the most efficient supply chains in the world – allowing the retailer to gain publicity for its incredible response to Hurricane Katrina, which offered relief aid faster than most government services could. Online retailers like Amazon operate massive international operations with extremely powerful tools to measure and track changes in demand. However, under a profit-motivated system, these tools have turned into means by which labour is further exploited and the agency of workers eroded as they are made more and more powerless.

Just as revolutionaries before us have seen the products of capitalism as tools that must be liberated for the betterment of people, we must look upon these intricate, data-driven networks of distributors and suppliers as an incredible example of the potential of labour. Unburdened by profit, freed from wage theft, it is possible to arrange, by democratic means, a world that could weather the Katrinas of the future, that could boldly confront the consequences of the foolhardy capitalist class’s gamble on carbon energy, that can build a world worth living in, even if the most disastrous predicted scenarios come to pass. The system that emerges as the product of capitalism’s breakdown will overcome its failures, but only if we can imagine beyond them.

For the time being, these potentially transformative powers lie tame, employed only in the narrow-minded pursuit of profit by corporations. The total level of control over consumers sought by these companies is extreme to a degree that makes the notion of “consumer choice” all the more dated. The wonder-work of capitalism captured in images of Khrushchev’s visit to an American grocery store, marveling at the laden shelves, is now firmly a dream of the past. Now, we are trapped by these stores, ensnared by mechanisms that were designed from the ground up to encourage us to spend excessively. Our attention, our opinions, our tastes and agency, have now all fallen prey to the same principles that built these commercial institutions. These are the tombs of capital, the final terminus of massive supply chains that have degraded and destroyed over half the world to ensure the near-constant presence of cheap consumer goods in this country, a mausoleum to our self-interest: a collection of products so numerous that we are not even equipped to take stock of them, products that we do not want, products that we do not want to choose from – our cup runneth over.

It is not enough that we cannibalise the husk of consumer capitalism for its modern efficiencies. We must combine this with an honest assessment of the benefits and failures of the past century and determine how to structure a new planned system. Reflecting on the Soviet experience and American responses to it, Seth Ackerman wrote an important analysis in Jacobin titled “The Red and the Black”. The old arguments over the benefits of economic planning, the role of the calculation problem, and comparisons between market solutions and participatory economics are continued, but Ackerman goes further, especially castigating the failures of neoclassical economics, noting that by neoclassical measures of efficiency, the Soviet economy was equivalent to or superior to the American market economy. Additionally, he notes the important and sometimes forgotten role that production of consumer goods plays in maintaining public confidence in economic planning, and the opportunity that provides the “neoliberal Right… [to measure] a society’s success by the abundance of its consumer goods.” However, his final recommendations, for a Frankenstein’s monster of economic planning at the broadest level, and tame little markets operating as efficient machines subservient to the master plan, is unsatisfactory.

A response to Ackerman’s “socialism in two steps” proposal can be found in Matthijs Krul’s article written in response, which provides a sound and forceful defense of economic planning. Krul argues that economic planning, both in the Marxist tradition, and in other forms, is a natural conclusion reached under the pressures of political and military adversary:

As soon as push comes to shove, and the liberal-democratic societies are threatened by total war, they approximate central planning in their production methods as closely as their political systems allow.

Aside from these historical and economic critiques of Ackerman’s article, one issue, which I will address here, stands out as particularly ill-considered. It’s not that Ackerman is necessarily incorrect in identifying the need for a division of the economy into separate productive spheres with varying degrees of efficiency; it’s that he does not fully conceptualise the potential of the technologies that are currently available to planners. For example, he criticizes the proposals of “participatory economics,” the prefiguration of a model of planned economies:

At the beginning of each year, everyone must write out a list of every item he or she plans to consume over the course of the year, along with the quantity of each item. In writing these lists, everyone consults a tentative list of prices for every product in the economy (keep in mind there are more than two million products in Amazon.com’s “kitchen and dining” category alone), and the total value of a person’s requests may not exceed his or her personal “budget,” which is determined by how much he or she promises to work that year.

Later, he comments that this “comes off instead as a precise demonstration of why economic calculation in the absence of markets or state planning would be […] impossible to imagine working in a way that most people could live with in practice,” adding that it violates the core Marxist principles of “from each need, to each ability” by imposing budgetary limitations based on the promises to work. But this is where the need to imagine further begins to emerge, written into the parenthetical describing the two million Amazon.com products available for kitchen and dining. How does Amazon organise those two million items, and the many millions more that it has in other categories? How do they maintain the supply chains necessary to offer overnight deliveries of these goods? We know of the morally reprehensible raw exploitation of their labor pool employed to offer this level of obscene convenience, but we talk less of the incredible networks of data that are used to develop their sales algorithms. These algorithms are tools; while currently they are used here by Amazon to maximize profit, at the expense of the consumer’s autonomy and the employee’s dignity, they could just as well be employed by economic planners to ensure the fair and expedient distribution of consumer goods.

Why, as Ackerman suggested, make only yearly budgets of price lists? Why not monthly, daily, up to the minute? This is not only technologically feasible, but if we are serious about keeping capitalist intrusion at bay in a planned economy, we must be cognisant of the potential resources that we can draw upon. These current systems of supply chains, as they exist in retailers like Amazon and Walmart, can be used to measure and simultaneously fulfill the demand for consumer goods, obviating the need to keep markets around to manage them as levels of production are intentionally lowered. If we want to nationalize Amazon, as has been suggested, then we must be prepared to make full use of the systems inherited under public control.

Predictive and other “smart” models that help arrange the systems that meet present day needs can be used to plan for future changes in demand, limiting risks of overproduction and scarcity, creating efficient connections between producers and consumers. This allows degrowth to be implemented without sudden shocks. Policies of degrowth that target particular sectors of the economy must be cognisant of this effect on other sectors. If, for example, we reduce emissions by investing in mass transit, we have to ensure that we are maintaining the quality of life and access to resources for residents of oil-producing regions fairly seamlessly, or else planners risk dividing working class interest, making these solutions into targets. A crisis of overproduction is not solved by a crisis of underproduction - in fact, focusing on redirecting economic resources from overdeveloped regions to underdeveloped ones is one of the most important features of degrowth.

Efficiency alone does not solve the crisis of overproduction, especially when this overproduction is guided by profit. This is where we must recognize and integrate ecosocialism in our planning, establishing goals that ensure protection of more fragile environments, development in economically gutted areas, and degrowth in over-developed areas.

Reorganising Ecosocialism for Planning

In Capital, Volume 1, Marx explains the relationship of what John Bellamy Foster later referred to as “metabolic rift,” as humans as a species are alienated, by capitalism, from natural processes

Capitalist production […] disturbs the metabolic interaction between man and the earth, i.e., prevents the return to the soil of its constituent elements consumed by man in the form of food and clothing; hence it hinders the operation of the eternal natural conditions for the lasting fertility of the soil. […] All progress in capitalist agriculture is a progress in the art, not only of robbing the worker, but of robbing the soil; all progress in increasing the fertility of the soil for a given time is a progress toward ruining the more long-lasting sources of that fertility. […] The more a country […] develops itself on the basis of great industry, the more this process of destruction takes place quickly. Capitalist production […] only develops […] by simultaneously undermining the original sources of all wealth—the soil and the worker.

Marx, without the ecological insight we have today, could not have possibly imagined the scale to which this is true, nor the reality that we could so disturb the source of our material wealth as to create a global crisis. However, he does produce a powerful summary of the dialectical relationship between capitalist production and ecological destruction. Socialists today, responding to our modern crisis, can therefore conceptualise the climate crisis as the product of these contradictory forces at play within capitalism, with profitable growth this destruction. To address this contraction, we must plan economies around long term ecological and economic stability. Worker self-management plus ecological stability is the answer we need to the capitalist abuse of these resources.

Ecosocialism may be a relatively modern development of socialist theory, but the ecological sciences owe a debt to the Marxist tradition. Important early figures in the formation of the field of ecology were brought to their conceptions of the natural world as an interconnected system through Marxist writings. J. B. S. Haldane, an evolutionary biologist active in the first half of the 20th century and a member of the Communist Party of Great Britain, incorporated communist theory with early ecological research. Haldane played a central role in the development of population genetics, unifying the theories Darwinian selection and Mendelian genetics. John Maynard Smith, a former CPGB member, was instrumental in the development of the concept of evolutionarily stable strategies, an extension of game theory into the ecological sciences. Today, socialists must develop and broaden a theoretical basis for ecosocialism through interaction and development of the field. John Bellamy Foster observes in an interview for Left Voice in 2017:

Natural scientists have done an excellent and courageous job of sounding the alarm on the enormous dangers of the continuation of business as usual with respect to carbon emissions and other planetary boundaries. But mainstream social science as it exists today has almost completely internalized capitalist ideology; so much so that conventional social scientists are completely unable to address the problem on the scale and in the historical terms that are necessary. They are accustomed to the view that society long ago “conquered” nature and that social science concerns only people-people relations, never people-nature relations.

Without active interaction between the sciences and socialist organizing, degrowth will remain a nebulous term, regarded suspiciously by organisers more steeped in traditional goals, viewed as a hard sell to a deindustrialised, demoralised and disenfranchised nation. However, the surging growth of vaguely anti-capitalist green movements must be capitalised upon by organisers who are comfortable with concepts like degrowth in order to forge a bond between these two deeply necessary planks of ecosocialist reform.

Degrowth is sometimes criticized as a “softer” left-wing proposal, an unattainable goal for the unserious and non-politically minded. However, it is an absolutely crucial tool in not just politically opposing economic imperialism, but in reversing its real-world effects. Imperialism is a causative factor for climate change. Through the exploitation of resources from a range of sources, imperialist economic development has accelerated the extraction and use of fossil fuels and encouraged ecological destruction at larger scales. Low cost consumer goods in the United States exist by virtue of a base of exploited industrial and agricultural producers in underdeveloped nations, and the ability of American producers to rearrange labour costs internationally with sophistication that exceeded the ability of the USSR to arrange labor in Warsaw Pact states (which caused enormous political stresses between the USSR and its satellites). These arrangements and rearrangements moved, for example, production of consumer goods from post-War Japan to Korea to Taiwan to China to the Philippines in sequence, as these countries developed. One after another, each experienced rising labour costs as a result of American investment, eventually reaching a point at which savings of labour in these countries was no longer higher than the cost of the construction and integration with infrastructure of a country at a slightly lower level of development, thus ensuring low manufacturing costs on a continuous basis for American producers.

Without the ability to offshore production costs in this way, it is not really feasible to domestically produce low-cost consumer goods at the quantities and at the quality expected by American consumers. Low international labour costs are necessary to the lifestyle of the American consumer, even though the majority of this cost is hidden or considered just a mundane fact of life; images of dreary, deadly sweatshops in Southeast Asia that may have once given pause to the decision to consume one brand over another now fail barely raise the blood pressure of American consumers as they go about their purchases. The networks of trade infrastructure facilitate these low costs by exploiting underpaid drivers, truckers, distributors, and delivery workers.

Degrowth targets these economic agents within the core and, rather than negotiating them to a lowered degree of exploitative practices, destroys their entire business model. This is a decisive and very positive direction to head in. We do not need the ever-inflating market of consumer goods to grow more and more bloated in years to come. We do not need to maintain a market for consumer goods dependant on dangerous and ecologically unsound supply chains. What we must avoid is the uncontrolled collapse of recession. Degrowth provides a structured manner to selectively remove power and economic agency from sectors of the economy deemed unnecessary in order to bring down the overall ecological impact of the economy as a whole.

Degrowth means lowered production of consumer goods. This means decreased profitability. This means that private companies will resist working with you, that producers will seek other markets for their goods. Without some structure to govern who can and cannot do business — that is, without economic planning — degrowth is unable to actually attack those who do the most damage. Socialism in the 21st century must be able to remain stable in the face of these crises, to defend itself from ecological collapse as well as the ravages of capitalist retrenchment. Degrowth provides that stability.

Climate change is an existential threat unlike anything seen before in the modern world. Capitalism has never needed to contend with a phenomenon at this scale. The increasingly abstracted and impractical methods invented by the ruling class to deal with this threat are transparent half-measures, none designed for success, and none decisive enough to effect meaningful changes. In response, we must develop a socialism that is practical, that responds to the present conditions of workers and the places they live, that knows this struggle is life or death.

Unfortunately, this desire for practicality is sometimes at odds with traditional interpretations of Marxist theory. Guided into a complacency of the “inevitable” collapse of capitalism and the inexorable historical replacement of the old system with a socialist one, the conclusion developed that the collapse of capitalism must result in a situation where socialist production emerges. This mode of thinking has been criticized extensively, but a more penetrating criticism of the language of Marx, and more broadly speaking, the language of European scientists in general, was outlined by Cedric Robinson in his landmark book, Black Marxism. Here, he quotes K. G. Davies:

From Darwin has descended the language of error, a language that has locked up historical thinking and imposed slovenly and imprecise conclusions even upon scholarly and sensible researchers. Words like “growth,” “decline,” “development,” “evolution,” “decay,” may have started as servants but they have ended as masters: they have brought us to the edge of historical inevitability

Socialism will not “grow” unless we build it, scaffold it, defend it; capitalism will not “decay” unless these structures are sufficiently empowered to act against capitalist intrusion into planned sections of the economy. These discussions must be based on plans that realistically reflect the historical moment we live in, and the material realities of productivity, environmental, and consumer needs. Degrowth is able to address this only in the case that it is built out of democratic, worker-driven governance. Economic planning is able to survive an environmental dangerous political environment only if it is driven by a meaningful response to the material threat of climate change as it pertains to workers. Otherwise, the grim example of deindustrialisation, which abandons entire communities from a broader economic network, would simply be reconstructed under a planned economy. We have no time to try to revive old dogmas, or to relive the ideological fights of the past. The future is here now, and we must answer this challenge in a calculated, practical manner, like our lives depend on it.