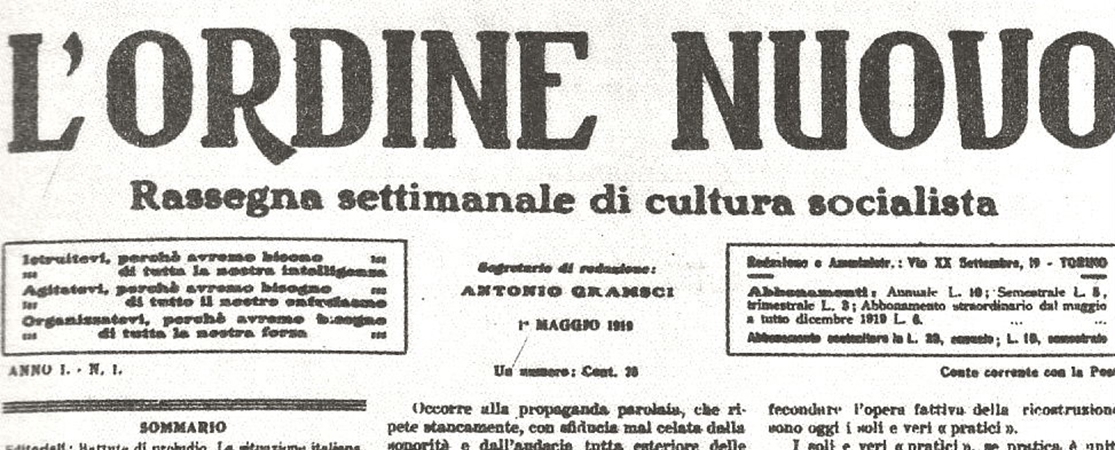

In advance of the TWT policy lab, what might a socialist media look like and how would it relate to other commitments to a democratised everyday life.

Labour party members and strategists have long been aware of the particular problems that the politics of the media in this country pose as a bar to electoral success. This was part of the rationale for the rightward drift of the party in the wake of the defeats of the 1980s, and Corbyn himself remarked in 2016 that the successes of the movement up to then were in part possible because of the declining influence of The Sun and the Today programme. But if the waning influence of ‘legacy media’ has opened up greater opportunities for transformative politics, it is also the case that the Corbyn project has faced an unprecedented onslaught from these same institutions, and not only from conservative media.

This poses a threat to socialists not only in undermining potential electoral support - which tends to be the focus of the moderate, electoralists amongst us. Relentless attacks from the media Establishment, in combination with a reliance on commercial social media platforms, demoralises, distracts and disorientates committed and potential activists. The vital efforts to develop our own media, meanwhile, still comes up against the perennial problems the left has always faced. Digital technologies have lowered the cost of publishing, but we still have nothing even approaching a sustainable left media. None of this is surprising given that the capitalist media system, which has always systematically disadvantaged the left, is itself now in crisis.

Left discussions of the media have tended to focus either on fostering our own media initiatives, working in or with the existing media institutions, or designing regulation to curtail the worst excesses of those institutions. All this is important, but we think it’s time for a much more radical and ambitious policy programme, one that transforms and democratises the media system. The capitalist media, like the system of which it is part, is in an unprecedented crisis, and any democratic socialist response must necessarily involve building a new media and communications system which will not only address the maladies of the current system, but can also form the basis of a wider democratic transformation of the economy and society.

In his Alternative MacTaggart lecture last year, Jeremy Corbyn set out a set of ideas which indicated a much more radical direction for the party on media policy. But none of this has been further developed by the party. The onus is on the wider Labour left to develop this agenda. To create a media for the many, we need a radical set of proposals and the energy and commitment to make them central to a transformative Labour programme.

We have been involved in organising a Policy Lab at this year’s The World Transformed that seeks to do just this. The event is on Tuesday the 24th of September at 9am in the Brighthelm Auditorium. It will bring together media workers, reform activists and party activists, giving participants an opportunity to put forward their own ideas and discuss and debate some existing reform proposals. We have each worked on media reform for some years now, and have been developing with others a set of related proposals that we think together represent a practical but transformative socialist agenda for the media. They include the democratisation of the BBC, establishing a British Digital Cooperative, and a system of publicly-funded co-operative journalism vouchers. We hope the TWT Policy Lab will provide an opportunity for the critique and development of these ideas and a range of other radical reform proposals. We want anyone interested to send their own proposals for socialist media reform (up to 600 words) to [email protected] to be added to a document for discussion at the Policy Lab alongside those ideas along with those we present below.

Radical Reform of the BBC

The BBC has been the leading broadcaster in the UK for almost a century, and continues to set professional standards and provide expertise, training and public revenue for the industry of which it is part. It is a major provider of online news and entertainment, and is by some way the most significant single news source for the UK public across platforms.

The BBC is nominally committed to certain values that should be safeguarded and rejuvenated for the digital age: accuracy and fairness in reporting, and independence from private power and political interference. But these values need to be re-embedded in the organisation by radical reform of the BBC and its relationship with its audiences. The top-down, statist structures that characterised 20th century broadcasting, with its highly politicised system of managerial and editorial control, should be overhauled. The BBC should instead become a democratic public platform and network, fully representative of its audiences, independent of both the government and the market.

In partnership with a new sister organisation, the British Digital Cooperative, a revamped and democratised BBC would become a central part of our digital future, offering free programmes and information, and providing a universal platform for citizens, assisted by algorithms that are transparent and subject to regular review.

In recognition of the transition to digital public media, the television licence should be replaced with a digital licence fee based on internet access rather than possession of television receiving equipment. The rate of the licence fee should be set by a new independent media regulator which would also regulate editorial standards.

Audiences should participate in the commissioning of journalistic investigation and research, and be given a formal role in assessing projects and output. External programme commissioning should be rebalanced, with the public funds currently allocated to multinationals reallocated to cooperatives and not-for-profits.

BBC programme making and commissioning should be organised regionally, but made available nationally and internationally – in the latter case with programmes being made available via other public service media organisations. Boards jointly elected by licence fee payers and staff, with guaranteed minority representation, should oversee each production region, whilst a democratically elected central board would provide organisational oversight and strategic planning. Audience research should be replaced with a new model of public engagement based on local, regional and national audience panels that are representative of the places where they live.

The British Digital Cooperative

Online platforms now play a crucial role in the organization of the economy and the conduct of social life. They are central points of access for news and current affairs content. The underlying technology was created through a vast, taxpayer-funded effort and British Digital Cooperative (BDC) will be established to ensure that further public investments benefit the population as a whole. The BDC’s mandate will explicitly require it to enhance political, economic and cultural democracy in Britain.

Working with a reformed BBC, the BDC will develop a platform architecture that will enable citizens to interact with one another in an online environment that they understand and can shape according to clearly defined principles. This surveillance-free architecture will provide a space where users can assess publicly funded journalism and discuss its implications. It will extend to other public sector and civil society organisations, allowing people to subject the powerful to much more effective oversight. It will also develop resources that facilitate real world social and political life, and act as a counter to the addictive, advertising-funded platforms provided by the commercial sector.

Established in a number of research, development and production centres in parts of the country that have suffered from decades of deindustrialisation and state neglect, the BDC will become a key driver of public sector innovation. The BDC will give its employees the maximum possible autonomy and bring them into a permanent and egalitarian working relationship with the public they serve.

The BDC will develop digital resources for the co-operative sector and for new institutions including the National Investment Bank and the National Transformation Fund. It will establish free and open source software standards that reduce costs in the economy by stripping out the monopoly rents currently enjoyed by a handful of private firms. Over time its platform resources will become venues where citizens can plan the future of the places where they live, and of the wider society and economy.

The structure of the BDC will be as innovative as its mandate. As a ‘public cooperative’ it will be a common property, owned collectively by the citizens and residents of Britain. Ownership rights will be exercised by representative mini-assemblies drawn by lot from the places in which the BDC operates, and from the country as a whole. The workforce of the BDC will enjoy defined rights in democratically organised workplaces. Every four years the BDC will organise a wide-ranging debate about its priorities. This debate will be staged on the platform resources developed by the BDC and will give every citizen an opportunity to reflect on how they want public investments in new technology to serve society and the individual.

Democratic Journalism: public vouchers for co-operative news production

Journalism is in an epic crisis of collapsing resources and low public trust. Both symptoms are traceable to a deeper crisis in the private, for-profit production of journalism as a commodity for sale whose origins are in the advent of an aggressively profiteering neoliberal ownership and management model. The crisis has now reached its culmination in the devastating impact of the internet on the profitability of journalism-as-a-commodity. Advertising revenue has migrated away to platforms like Google and Facebook which distribute news but do not produce it. And the public generally aren’t prepared to pay for journalism now when they can easily access information for free.

This is a problem the market not only hasn’t solved, but can’t solve. Liberal journalists and commentators have waited for over a decade for a ‘digital business model’ to arrive but so far only media for the elite has proved remotely profitable. Yet the market was never really a good provider of journalism in the first place. In the mid-twentieth century golden age it meant ample resources, especially at ‘quality’ titles for the elite, but it also meant that a small class of wealthy proprietors had ownership and control. In time, falling profitability meant they had to give way to consolidated newspaper chains run to maximise shareholder value, and media conglomerates like Rupert Murdoch’s News Corp. Capitalist ownership and control has always compromised journalists’ ability to use their resources to produce anything other than pro-business, pro-elite journalism. The result has been news media which mostly turns a blind eye to our society’s deepest structural flaws and instead redirects public anger towards a selection of scapegoats - usually the marginalised, the oppressed and their political defenders on the left.

The collapse of commercial journalism is also a historic opportunity to establish a new and vastly better system of journalism production, one that recognises journalism ought to be a public good, publicly-funded for everyone to enjoy for free and not exclusive to those who pay. But equally, the state should have no hand in controlling who receives public funding. It is the people themselves who should decide directly.

Democratic Journalism would realise these principles. Its most basic feature is that each UK adult would get an annual voucher of £120 to spend on non-profit co-operative journalism. 14-17 year-olds would get a £60 voucher. Vouchers would be cast like electoral ballots, at polling stations each May. Each voucher would be split in half: one half to spend in a regional pool, the other to spend in a national pool. These halves could be divided up among as many or few recipients as voters want. To compete for funding, journalists would have to run, either as individuals working on their own or as non-profit co-operatives, in either one of the twelve regional pools or the national pool. They would have to accept rules guaranteeing good standards in the profession: minimum and maximum salaries; no use of unpaid interns; regulation covering journalistic standards, redress for members of the public, financial probity, and full disclosure of other financial interests. The regulator overseeing this system would be completely independent of the state, its board elected partly by working journalists and partly by the public. The whole system would be funded by a big new tax on advertising, between 10-20%. (Sweden uses a 3% tax to help fund its news subsidies.) A tax on public relations services could also be used.

Journalists would have to win and maintain support to get funding. Therefore, in order to exist, co-operatives would need to cultivate and sustain a level of public trust and belief in their work inimical to most current British journalism. Journalists representing minority identities, interests and views would have an unprecedented opportunity to establish their own self-managed organisations and flourish. A thousand new institutions would grow, and in each, journalists could do the socially useful work they and the public agree through an ongoing democratic conversation that they should do. They could walk away from the shoddy, compromised and actively harmful work that suits reactionary, megalomaniac media barons and profiteering shareholders. Those repulsed from the profession by the thought of having to do such work as the price of career progression could now enter it. The public would have free access to everything the system produces, giving them more choice than the private market could ever provide. The result could be journalism finally adequate to the needs of a democratic society.

Conclusion

All three of these proposals have been developed in the spirit which currently animates much of Labour’s most radical and innovative socialist ideas: that we must extend common and social ownership, and challenge the primacy of the market, but that we must do so with new, democratic forms of ownership and control which do not repeat the mistakes of statist postwar social democracy. Each of our proposals enables the public to become active participants who debate and decide for themselves what they want our media system to produce and to be, not just passive consumers of an output buffet whose quality, range and limits are determined by what political, capitalist and managerial elites believe the public wants, needs or is capable of understanding.

Those beliefs are inevitably shaped by their own patronising beliefs about public intelligence, as well as by their own interests in maximising profit and manufacturing consent to the established order. For many workers in media organisations, these elite interests are ones they must further, or at least respect, in their work. Our proposals aim not only to extend new rights of participatory democracy to the public, but also to give new and unprecedented freedom from subservience to media workers.

We believe that each of the three proposals outlined above has merit taken in isolation. But we intend them to work together. The British Digital Cooperative will provide resources to help a reformed BBC to become a public media platform, a space where democratic values trump the profit motive. Public funding through a voucher system will support journalism and research that is marginal or non-existent in the current media system. A public platform architecture with the BBC at its centre will provide multiple avenues for this more diverse journalism to reach large and politically consequential audiences.

Information, ideas and proposals that are inconvenient to the rich and powerful will become matters of sustained and widespread deliberation. The mystifications that do so much to secure consent for inequality and injustice will no longer be protected.

But these three proposals by no means exhaust the possibilities for radical media reform. In the digital space vital work is being done on the idea of ‘platform cooperatives’. The regulation of media standards, while insufficient on its own, is a necessary part of a good media system; yet the failure to implement the Leveson proposals for press regulation, coupled with the emergence of largely unregulated digital spaces means we are still far short of the regulation we need. Media ownership is more highly concentrated than ever and much of the population has little exposure to content that challenges the right-wing press in any meaningful way. The effect of election propaganda on voters only highlights the overwhelming tendency of political coverage to denigrate attempts to challenge the established order.

The construction of a broad, radical agenda for media reform is vitally necessary to reassert socialist values against the current, neoliberal common sense. The establishment of a radical new media system is an essential condition of sustaining other political gains, and achieving a future socialist transition.

Again, anyone interested can send their own proposals for socialist media reform (up to 600 words) to [email protected] to be added to a document for discussion at the Policy Lab on Tuesday the 24th of September.