Billy Bragg’s 1985 hit remains both a rallying cry and a warning.

“Bring up the banners from the days gone by!” The line from Billy Bragg’s 1985 hit, ‘Between the Wars’, can be heard as both a rallying cry and a warning. A warning because, in dark times, “days gone by” can offer sentimental consolation for escapists – here, for the promise of the welfare state’s “path from cradle to grave”. But it can also offer rigidly pessimistic parallels for realists: the mid-80s as an electoral doldrums for a radicalised Labour Party, creating the political space that facilitated Labour’s long march to the right. In each case, ‘Between the Wars’ becomes a site of mourning for class politics and for the modest utopianism of democratic socialism: “I paid the union and as times got harder / I looked to the government to help the working man.” Well, good luck with that, we might say (while wondering what became of working-class women). Yet the power of ‘Between the Wars’ is that it is aware of both the trap of sentimentality – the song’s invocation of “draughtsmen” and “craftsmen” was quaint even in 1985 – and the pitfall of pessimism (“they brought prosperity down at the armoury”), while remaining a rallying cry.

That ‘Between the Wars’ operates on several levels is signalled by its title, which summons both the period between the First and Second World Wars and the time between Second and Third World Wars: otherwise known as the Cold War. It also invokes the ongoing class war. In the same spirit then, this essay argues on several fronts: it examines the specific historical and political context of ‘Between the Wars’; it explores the political parallels between the mid-80s and now; it analyses the concept of ‘hauntology’ and asks how – and why – we should confront the past through culture; and via all of the above, it looks to the future from this post-election low point.

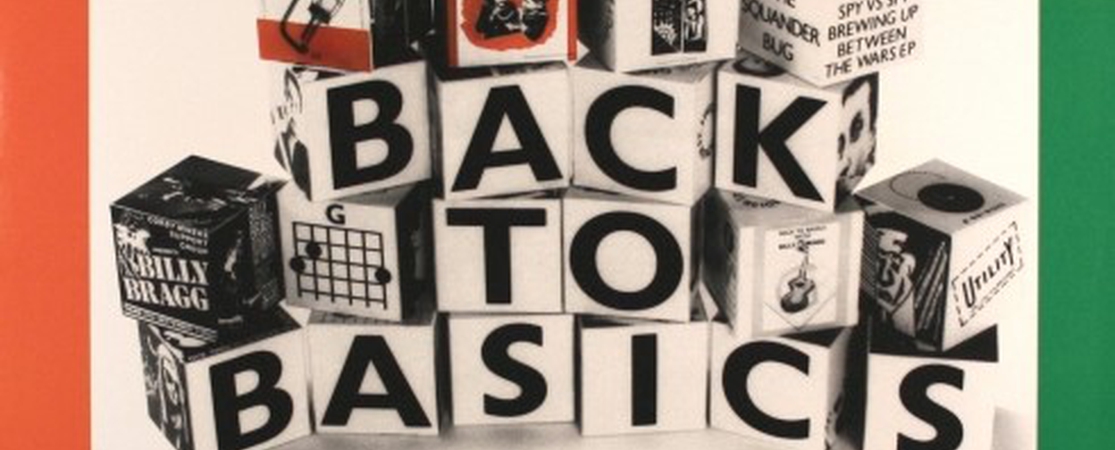

‘Between the Wars’ was released in February 1985, just weeks before the end of the British Miners’ Strike. With the EP’s proceeds going to miners’ support groups, it entered the chart at the end of the strike, rising to UK number 15. In keeping with ‘Between the War’s time-travelling militancy, the EP also included a song about the Diggers (Leon Rosselson’s ‘World Turned Upside Down’), a 1930s trade union song (Florence Reece’s ‘Which Side Are you On’) and Bragg’s own song about media bias (‘It Says Here’). The parallels then are unavoidable, so let’s get them out of the way.

Both ‘Between the Wars’ and the miners’ strike came in the aftermath of Labour’s catastrophic 1983 election result, which saw an embattled left-wing leader, Michael Foot, together with a left-wing manifesto, battered by the press and rejected by the electorate. The class warfare of the miners’ strike was not the only contemporary manifestation of the left’s resistance to neoliberal hegemony, however: the previous year Liverpool Council had rejected Margaret Thatcher’s government’s rate-capping, leading to a mass refusal by national councils to budget within legal limits. The GLC’s key role in this was led by one John McDonnell; the fight was still ongoing in March 1985. Labour’s new leader, Neil Kinnock, having supported neither councils nor miners, was emboldened by their eventual defeats that year to push further rightwards. At the Labour Party’s conference in October, Kinnock declared:

“I’ll tell you what happens with impossible promises. You start with far-fetched resolutions. They are then pickled into a rigid dogma, a code, and you go through the years sticking to that, outdated, misplaced, irrelevant to the real needs.”

What is arresting about this speech now is less its specific targeting of the unlovable Militant Tendency, but its broader anti-utopianism, its lowering of horizons, its reification of defeatism.

So the parallels are such that a song from 1985 can speak directly to our present moment. We are again in a “time of austerity”. We are again “between the wars”: since 2001 we have been squeezed perennially between Iraq and the next war in pursuit of ‘security’ (“We’re arming for peace, me boys”), while the class war is ramped up. The left is again electorally defeated and the Conservative right mandated, as Thatcher was in 1983, to turbocharge radical neoliberalism (“Theirs is a land with a wall around it”), rooted in authoritarianism (Bragg’s “the iron fist”) and overlaid with a rancid, nativist nationalism (“theirs is a land of hope and glory”). The Labour right is again emboldened: with centrists currently sharing clips of Kinnock’s 1985 speech, the parallels between Momentum and Militant are both inaccurate (Momentum might benefit from Militant ruthlessness) and chilling (a call to purge the party). Bragg’s line, “sweet moderation, heart of this nation” is thus a field of contestation as never before: if these bile-spewing politicians and pundits are Labour ‘moderates’, then how do we begin to understand the moral, let alone the political meaning, of ‘moderation’? Bragg’s lyric is a timely reminder of the sheer reasonableness of democratic socialist demands; the values of fairness and decency (“the helping hand”) which are currently being drowned out by a roar of recrimination, classism and the risk of concessions to a right-wing “culture war” within Labour, and a gloating, boot-stamping triumphalism from the Tories.

Showing the constraints of parallels, there is a crucial difference, however: the mid-80s was an ending of something, while we are barely getting started. The key players of the 80s – Foot; Healey; Benn – were ageing 60s and 70s holdovers who’d held power and lost it. What was new in the mid-80s – Kinnock; Blair (elected as an MP in 1983) and Brown (again elected in 1983) – was ‘left’ neoliberalism. However, it is that project which is now exhausted, that project whose ageing cohort – Blair, Brown, Cooper, Johnson – have lost not only power, but vote share and – post-Iraq and financial crash – moral standing. Our new cohort of left politicians is, yes, untested, but the better for it, with youth on their side and energy and ideas to burn. Similarly, the miners’ strike was, arguably, the last gasp of the Long 1970s: the final fling of militant unionisation. What was new in the mid-80s was a post-strike working class quietism, causing the Long 1980s to effectively last until the mid 2010s. That the left is barely getting started on working class mobilisation was a flaw in Labour’s 2017 and 2019 campaigns, but again the space is open for ideas and action. What’s more, the crucial difference here is that Labour has ideas about the future; the Conservatives and the Labour right don’t.

It is ‘Between the Wars’ invocation of such a future – its utopianism – that makes it enduringly relevant. It is also by restoring the idea of the future, I would argue, that we can rescue ‘hauntology’ from both its connection to the political fortunes of the Corbyn project (remember ‘Acid Corbynism’?) and its potential for political enervation (internalising that “slow cancellation of the future”). Mark Fisher quotes Wendy Brown’s channelling of Walter Benjamin on “left melancholy”, but does not linger upon either left melancholy’s links with hauntology (“a Left that is thus caught in a structure of melancholic attachment to a certain strain of its own dead past, whose spirit is ghostly”) or Brown’s ‘realist’ conclusions: more discourse analysis, more postmodernism, less utopianism! So to regard an 80s song like ‘Between the Wars’ as ‘hauntology’ is a departure from – or an expansion of – ‘canonical’ hauntology, which, via Fisher and Simon Reynolds, is associated with post-millennial music and thus – however uneasily – with postmodernism. To shed that association with postmodernist defeatism and give broader application to the concept, I would argue that ‘hauntology’ should be applied to cultural productions right across history. Culture has always looked back and what Raymond Williams called “retrospect as aspiration” (in The Country and the City), avoids the traps of escapism and pessimism and posits the past as way to inspire the present and imagine the future.

To begin with the song’s context then, ‘Between the Wars’ forms part of an alternative cultural history of the 80s, a reminder that, despite Kenny Loggins’ ‘This is It’, Madonna’s ‘Material Girl’ or Robert Palmer’s ‘Simply Irresistible’, capitulation was not the only response in neoliberalism’s cultural foundry. Most people’s first contact with ‘Between the Wars’ was – and is, via youtube– Bragg performing the song on Top of the Pops on 21 March 1985. Bragg’s performance is both a performative and a material assertion of the sweat behind the era’s sheen; of the grit behind 80s gloss; of the lived reality of working class life in the face of its 80s elision. Tracking back on the show, Bragg is flanked that week by Nik Kershaw – whose ‘Wide Boy’ bespoke the width of his lapels and shoulder-pads – by suited and tied Phil Collins and Phil Bailey, rock stars as middle manager. These artists mime their glib lyrics – articulating respectively: casual class hatred, casual misogyny and … nothing – amidst slick, modern sonic productions. Consequently, both musicians and songs appeared processed, immaterial, neoliberalism as simulacra – less ectoplasmic than simply insubstantial. Bragg, meanwhile, in short-sleeves and jeans, sings and plays completely live, backed only by his raw, skeletal electric guitar, articulating a lyric of blunt political refusal in a raw Essex accent. Rawness almost disappeared in 80s music, as synthesizers, drum machines and sequencers eclipsed humanly performed content, TV studios prioritised controlled miming over risky live performance (a metaphor for New Labour if ever there was one), and transatlantic accents replaced the British demotic punk had briefly promoted.

The song then is an assertion of enduring working class reality, despite its proclaimed death (see Eric Hobsbawm’s 1978 essay ‘The Forward March of Labour Halted’ and Marxism Today throughout this era – both quoted on Blue Labour’s Twitter page). “I raised a family / In time of austerity / With sweat at the foundry”. I remember such lyrics being sneered at in the corridors of my Kent school as oafish, un-lyrical, Luddite. Yet despite my classmates’ morass of mullets, espadrilles, legwarmers and blonde highlights, the Kent coalfields were only a few miles away, and I had stood with some of those classmates on picket lines, at Women Against Pit Closures’ stalls and at a miners’ benefit at which Bragg played this very song. So if the song asserts working class experience as lived reality, does this not contradict hauntology’s defining ethereal, anti-realist, larger-than-lifeness? The success of the song, as I hear it, is to combine the real and the ethereal, to render the material – dialectically – haunting.

First, musically, ‘Between the Wars’ is a revenant of both punk and the folk revival, a time-travelling channelling of The Jam, The Clash, Woody Guthrie and Ewan MacColl which is, surely, hauntological of itself. While, in such a stripped-down context, the merest hint of reverb on an electric guitar creates eerie wonders – a kind of ectoplasmic punk – the vocal melody, drawing on British and American folk, and the hymnal, has the ‘otherness’ of age alongside the immediacy of the contemporary. Second, lyrically, the song presents material existence in a mythic register that far transcends ‘Between the War’s being ‘about’ the miners’ strike in any literal sense. The song’s mythic register renders its narrator an everyman – docker and railwayman, as well as miner (allowing for that ongoing privileging of male experience). That same mythic register also channels a larger history: a radical British working-class tradition that encompasses the Peasants’ Revolt, the Diggers, Levellers, Luddites, English Jacobins, Owenites, Chartists, the Socialist League of William Morris, the General Strike and the union militancy of the Long 1970s. So the line, “theirs is a land with a wall around it” manages to summon enclosure, private property, gated communities and the metaphorical “walls” that uphold the class system. “Mine is the green field and the factory floor” summons working class history from feudal serf to industrial proletariat, while also invoking the Diggers’ “common treasury for all”, ‘Jerusalem’s “green and pleasant land”, as well as an organic, graspable ecology. Contrast this with the image of the ruling’s class’s “skies all dark with bombers”. The lyric then culminates in an invocation of the social contract between government and labour: “and I’ll give my consent / to any government / that does not deny a man / a living wage.” This line can be read as capitulation, but the power the working class wields in this contract is made very clear.

Despite – or because of – the song’s genesis in defeat (it was also played at the GLC’s farewell party), it is aware of the traps of the past: the lure of melancholy, of lionising failure. As such the lines, “Call up the craftsmen, bring me the draughtsmen / build me a path from cradle to grave” for me echo E. P. Thompson’s “I am seeking to rescue the poor stockinger, the Luddite cropper, the ‘obsolete’ hand-loom weaver, the ‘utopian’ artisan - and even the deluded follower of Joanna Southcott - from the enormous condescension of posterity.” The left can value their forbears, defeats and all, without getting trapped in an ontology of failure. Indeed, for those who can remember Tristram Hunt and John McTernan, their interest in the Civil War and the I.W.W. (the Wobblies), or the centrists who furiously insist that they are “left wing” on social media mark the ‘moderates’ as being the true melancholics. As Mark Fisher glossed Wendy Brown in Capitalist Realism, the left melancholic is “a depressive who believes he is realistic; someone who no longer has any expectation that his desire for radical transformation could be achieved, but who doesn’t recognise that he has given up”.

‘Between the Wars’, by contrast, channels but does not embrace left melancholy; it mines but does not get trapped in the past, and instead looks forward, refusing to surrender a utopian vision of the future. “Go find the young men never to fight again” coexists with the next line, “Bring up the banners from the days gone by.” Most haunting of all however, is the declaration that follows “theirs is a land with a wall around it”: “And mine is a faith in my fellow man”. While again, the gendered vocabulary dates the song, the narrator is rearticulating ‘nation’ as the family of man(kind), and is thus replacing the divisions of nationalism with the solidarities of humanism. Lyrically and musically then, ‘Between the Wars’ is a refusal: of political obedience, of manufactured ‘modernity’ – be that pop music’s sonic orthodoxy or the death of the working class – and of the cancellation of the future. The song is simultaneously elegiac and utopian, nostalgic and forward-looking, realistic and optimistic. It is these tensions that make it transcendent, and that give ‘Between the Wars’ its hauntological luminosity and thus its enduring relevance.