Universities are not just ‘marketplaces of ideas’ – the fight against racism and fascism must take place in academia as well as on the streets.

In the week that Niall Ferguson has used a newspaper column to call for a NATO-like organisation to ‘protect’ the freedom of speech, it is also worth noting that this week is the 45th anniversary of the introduction of the ‘no platform’ policy by the National Union of Students (NUS) in the UK. At the April 1974 NUS conference, the resolution for student unions to deny a platform to ‘openly racist or fascist organisations or societies’ and prevent them having a presence on campus ‘by whatever means necessary’ was passed. The resolution was part of a wider resolution dealing with the discrimination faced by overseas students in Britain and was a response to the rising threat of the National Front (NF) in the early 1970s. On the back of the 1973 oil crisis and the controversy over the acceptance of Ugandan Asian refugees in 1972-73, the NF were making headway as a right-wing political vehicle, primarily for disaffected Tories. Over the last few years, the NF had fostered an intimidating presence at British universities, breaking up several left-wing meetings and harassing student protestors.

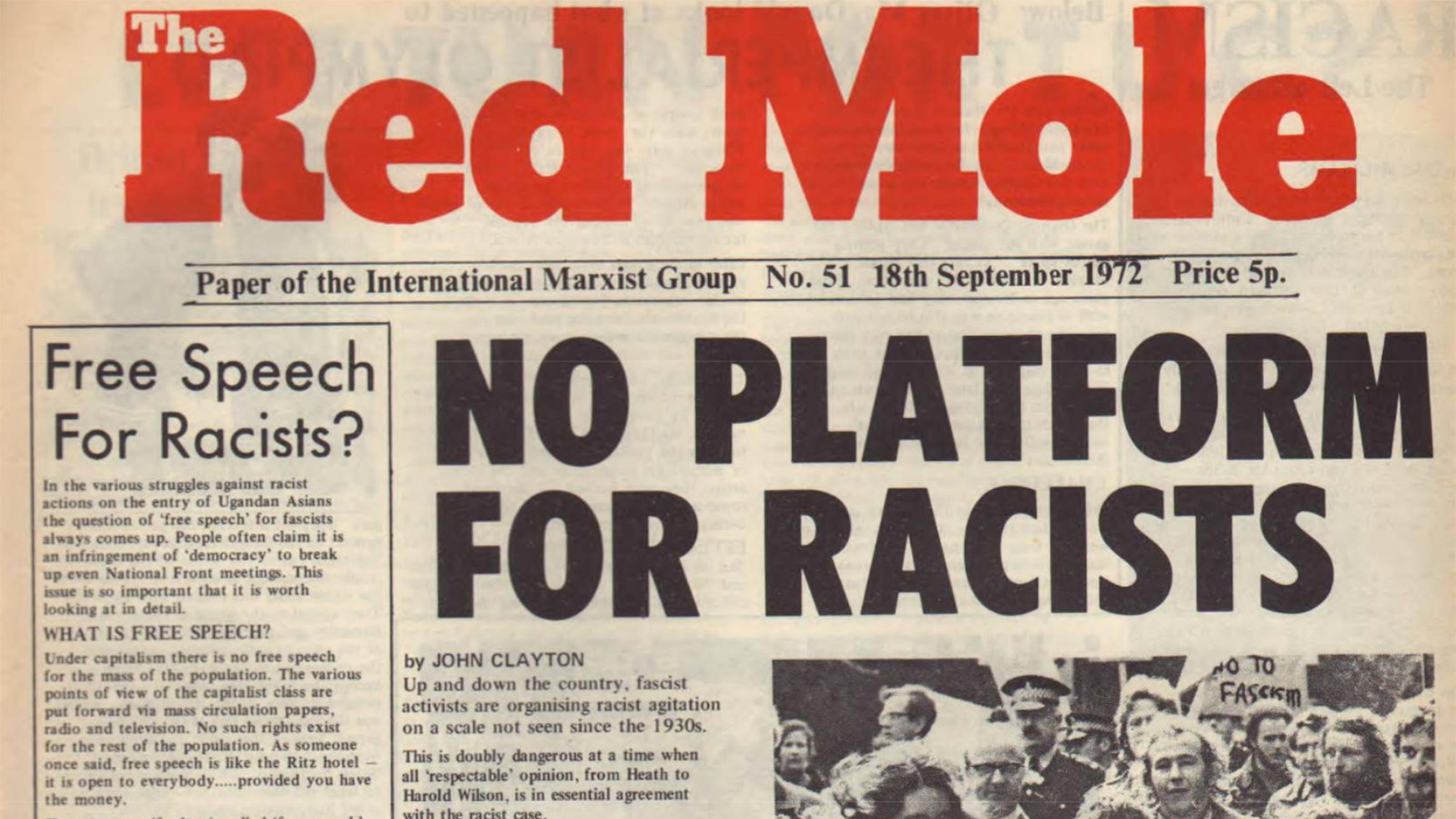

Promoted by the student left representatives from the International Marxist Group (IMG) and the International Socialists (IS), it was also supported by the Broad Left faction within the NUS (which was an alliance of the Communist Party and left Labour students). The phrase ‘no platform’ had first been used by the IMG two years earlier and the idea of ‘no platform’ was based on a long-standing anti-fascist tactic of denying fascists the physical space to organise, meet and recruit. Since the late 1960s, there had been impromptu protests at various universities against right-wing speakers, such as Enoch Powell, and by 1973, these had grown increasingly confrontational. In May 1973, the racist psychologist Hans Eysenck was assaulted by Maoists at the London School of Economics, which caused panic amongst the press, politicians and some within the universities. The ‘no platform’ policy, although driven by the far left of the student movement, was actually a bureaucratic measure that formalised the ad hoc protests that had occurred over the last half decade.

The policy was controversial from the start, with several student unions declaring that they would not enforce the policy at their universities. It was so hotly debated that the NUS held a special conference in June to further deliberate the policy. However the special conference was held on the same weekend in London as a major NF event at Red Lion Square. There was a large counter-demonstration that was attended by many of the students who were also attending the NUS conference. The confrontation between elements of the crowd and the police outside Conway Hall that day led to a number of injures and the death of one protestor. The ‘no platform’ policy was being debated as word filtered back from Red Lion Square about the actions of the police. The news of this possibly contributed to the NUS representatives voting to maintain the policy.

From this time, the policy has remained in place (except for a brief period between December 1977 and April 1978), but has been continually contested from sections of the NUS and the wider student body in Britain. For example, in 1977, the application of the ‘no platform’ policy to pro-Israel student groups caused considerable controversy, with the NUS leadership censuring the student unions that did this and the temporary suspension of the policy in total.

In the early 1980s, several student unions expanded the ‘no platform’ policy to apply it not just to fascists and racists, but also sexists (including some pro-life speakers) and homophobes. This happened at a time when the left (including the student left) was re-evaluating the relationship between traditional class-based politics and the new social movements that had emerged in the 1960s and 1970s, increasingly referred to in the 1980s as ‘identity politics’. Anti-racism in the form of anti-fascism was taken seriously by the left and the student movement, leading to the enforcement of the ‘no platform’ policy against explicit fascists and racists, but issues of sexism and homophobia were still sidelined by many on the left. The call for the ‘no platforming’ of sexists and homophobes can be seen as part of a broader push for the recognition of the politics of identity to be included in the outlook of the student left in the 1980s.

Meanwhile some of those who, in the 1970s, promoted the tactic of ‘no platform’ in the student movement, and within the anti-fascist movement more generally, disagreed with the expansion of the ‘no platform’ policy. They argued that ‘no platform’ was created with the original purpose of opposing the threat of organised fascism on campus, such as that presented by the National Front. They felt that sexists and homophobes, while offensive, did not present the same kind of threat as the fascists that the policy was originally developed to combat.

However the ‘no platform’ for sexists and homophobes needs to be seen in a wider context of the student unions attempting to address the sexual and homophobic harassment and violence experienced by students, both on and off campus. Like the ‘no platform’ for fascists and racists line taken by the NUS, the policy of ‘no platform’ for sexists and homophobes was not just an action to be taken against certain types of speech, but saw these forms of speech as precursors to acts of violence which required a pre-emptive response. This is very similar to the approach taken today to ‘no platform’ transphobes by various student unions - transphobic speech contributes to a culture where transphobic violence is increasingly normalised, which requires pre-emptive action to prevent the pronouncement of transphobic ideas on campus.

From the early days of the policy, there were concerns that student unions would ‘no platform’ Conservative MPs and individual student unions attempted to this, ignoring the guidance of the NUS that Conservative Party speakers were not to be subject to the policy. In 1978, Sir Keith Joseph was ‘no platformed’ at LSE and the Immigration Minister Timothy Raison was also ‘no platformed’ in 1980 at the same institution. The Raison incident partly contributed to the LSE student union reversing its ‘no platform’ policy, with Daniel Finkelstein being one of the proponents of this change.

Between 1985 and 1987, the issue of protests against visits from hard right MPs to university campuses came to a head with several MPs being confronted by protestors, sometimes leading to violence. The hardline Federation of Conservative Students (whose last Chairman was current House of Commons speaker John Bercow) and Conservative Associations at various universities invited controversial speakers, with many suggesting that this was being done for notoriety and to provoke reactions from the rest of the student body.

In March 1985, Home Secretary Leon Brittan visited the University of Manchester where a large crowd of students clashed with the police. In early 1986, pro-South Africa Tory MP John Carlisle attempted to speak at several universities, which resulted in being assaulted at Bradford University and denied a platform at Leeds Polytechnic, Oxford University and the University of East Anglia. Later in the same year, Enoch Powell was disrupted by protestors at Cardiff and Bristol University. At some of these protests, the policy of ‘no platform’ was evoked, but others it was not. A number of the protests and disruptions were conducted despite the efforts of the student unions to dissuade more militant students and protestors from taking action. The NUS endorsed ‘no platform’ policy at the national level made a distinction between fascists (who were to be ‘no platformed’) and hard right politicians (who were to be allowed to speak) but was often ignored by more militant protestors from the left. The various disruptions, such as at Bradford and Bristol, showed that disruptive protests happened outside the bounds of the politics of the student union.

These protests led to the Thatcher government attempting to curb the use of ‘no platform’ by student unions through the Education (no. 2) Act 1986. This legislated that universities and colleges needed to ensure free speech or risk government support. However this did not seem to stretch to student unions, who were separate legal entities (although operating on university grounds). Within a few years of the 1986 Act coming into effect, some Tories were still complaining about the supposed lack of free speech on campus. University administrations also used compliance with Public Order Act 1986 to dissuade certain speakers from visiting, citing public safety concerns. This was challenged in court by conservative students at the University of Liverpool in 1989-90, which suggested that there were limits to public disorder concerns with regards to allowing controversial speakers on campus, but since then, universities have generally erred on the side of caution.

Since the early 2000s, a number of student societies dedicated to ‘free speech’ and ‘liberty’ have popped up on various universities across the UK and have been involved in reviving attempts to bring controversial speakers onto campus. In 2001, the Free Speech Society at Leeds University invited the British National Party’s Nick Griffin to speak, as two of the society’s leading members were also members of the BNP at the time. More recently, the Liberty Union at the University of Kent invited at different times disgraced columnist Katie Hopkins and Youtuber (and now UKIP MEP candidate) Carl Benjamin (better known as ‘Sargon of Akkad’) to speak. Both the Oxford and Cambridge Unions have invited fascists and racists to debate, including Nick Griffin, Holocaust denier David Irving, English Defence League co-founder Tommy Robinson and Front National’s Marie Le Pen. While Tommy Robinson has had his YouTube content somewhat restricted, video of his appearance at the Oxford Union in 2014 has reached over 1.5 million views of the Union’s own YouTube channel.

The recent outcry over ‘no platform’ at British universities, as well as elsewhere in the English-speaking world such as the USA, Canada, Australia and New Zealand, has come at a time when the far right is in the resurgence. In the 1970s, ‘no platform’ was used as a tactic against an advancing far right, seeing the university as part of a wider battle ground in the struggle against fascism and racism. In many ways, a similar sentiment can be seen today. Universities are not just ‘marketplaces of ideas’, removed from the rest of the world – fighting racist and fascist ideas means they need to be challenged in the lecture theatre, seminar room and debating hall as much as on the streets and in the electoral sphere.

Part of the contemporary complaining about ‘no platform’ and the alleged lack of free speech at universities comes from white, male and straight academics at a time when students are starting to discuss ideas around deconstructing and decolonising universities and academia. As Dawn Foster recently pointed out, complaints about free speech come from those who have traditionally been allowed to speak without much pushback and now that there is criticism of their arguments, they are claiming to be ‘silenced’ (often making these complaints from the pages of national newspapers or television).

Former Education Minister Jo Johnson launched a parliamentary inquiry into free speech at universities in late 2017 and in 2018; it concluded that the threat to free speech on campus was highly exaggerated. But that has not stopped the right from waging a cultural war on this issue, resurrected in modern times to attack their critics in a period where their ideas are being challenged – on campus, on social media and in the streets. Niall Ferguson’s call for a NATO-like organisation may be over-the-top hyperbole, but it is part of a broader movement to maintain the status quo against a new generation of students and youth who are less likely to acquiesce to their out-of-date ideas. Although there are times when the policy of ‘no platform’ has been controversially applied, there are clear reasons why it has lasted for 45 years, and why it is still important now.