At a recent meeting discussing a Universal Basic Income, one of the speakers expressed surprise that women would demand a wage for their work, his assumption being that our work was a labour of love.

At a recent meeting discussing a Universal Basic Income, one of the speakers expressed surprise that women (who still carry out the largest share of domestic and reproductive labour in the home) would demand a wage for their work, his assumption being that our work was a labour of love.

With my new baby strapped to me I was feeling the sharp end of the wedge of reproductive labour. It hadn’t occurred to me that people on the left still saw the invisible, unpaid work carried out in the home as not deserving of a wage - or to put it more strongly that the workers carrying out that work (predominantly women and mothers) are not justified in making demands for a wage.

As Silvia Federici says in Revolution at Point Zero,

The unwaged condition of housework has been the most powerful weapon in reinforcing the common assumption that housework is not work, thus preventing women from struggling against it, except in the privatized kitchen-bedroom quarrel that all society agrees to ridicule, thereby further reducing the protagonist of a struggle. We are seen as nagging bitches, not as workers in struggle 1.

It is undoubtable that Jeremy Corbyn’s recent success marks the biggest step forward for the left in a generation and with that a great advance for women’s rights. There is so much in the manifesto that will improve the lives of women in the workplace, in education, in healthcare and in the home. Yet, there are still many more demands that women can and should be making on the Labour Party.

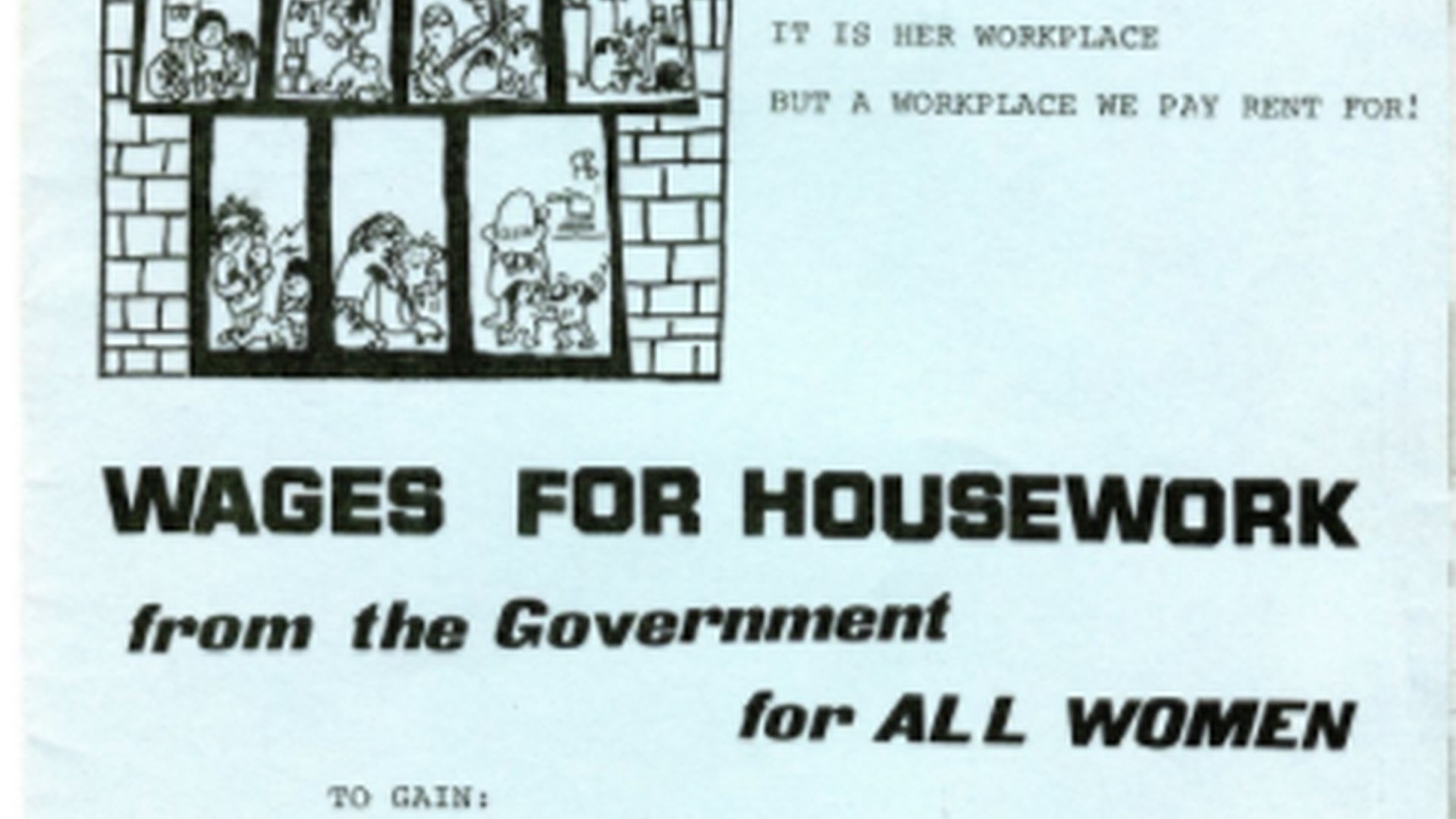

The Wages for Housework campaign led by feminists in the 70’s was an attempt to politicise domestic labour, to frame a demand that’s natural conclusion was the necessity of women’s collective struggle. It rightly sought to identify women’s role in the home as unrecognised, uncompensated labour. If the very existence of capitalism is dependant on this labour (the creation and raising of new workers, the care and servicing of current workers) it wasn’t simply the men on the factory floor that needed to organise against their exploitation but the women in the kitchen too.

Times have clearly moved on and it’s fair to say that the situation for women now is less restrictive. However the recent debate within the Labour Party around a Universal Basic Income has once again brought the idea of Wages for Housework to the fore.

Removing what is often seen as a binary decision between work at home and work outside the home - we should be demanding a system whereby the situation is more fluid and women and parents have the ability to fluctuate more easily between the two with an acknowledgment that when a parent is at work inside the home it is still just that - work, that their role should not be diminished in any way simply because they are not employed. I’m sure I’m not alone in feeling a sense of the work I do at home as being invisible to the rest of the world. Whether or not the Wages4Housework demand is deemed realistic, the cornerstone of the demand and one that deserves a hearing is one of validation for the role of unpaid labour.

The shape and semantics of the demand - whether we call it wages4housework or a basic income are almost less important than what the demand represents, because the natural consequences of raising it address the structural impact of unpaid domestic labour on women working outside the home. Such a demand should be linked to the experiences of low paid women - not simply as a tool for solidarity but as a practical organising tool that shifts the debate around low pay to a clear analysis of class, race and gender.

You are more likely to work in a low paid job if you are a working class woman, this increases if you are a woman of colour and/or migrant worker. While there are various structural, historical and economic reasons for this, one over arching theme is that women’s work is often seen as an extension of the unpaid work women do in the home - child raising, caring, cleaning - if it’s unpaid in the home why should it be highly paid outside of it? The two are inextricably linked. A wages4housework demand is not some lofty, ideological, outdated, feminist demand - it is directly rooted in one of the causes of low pay for women in today’s society.

Think of the role of the women working at the Ford Dagenham car plant that went on strike to demand equal pay. Their work at the plant was portrayed as inconsequential, little more than what they already did in the home, a little bit of sewing - until they organised collectively and their strikes brought production to a stand still. The diminished role of women in the home reinforces the view that it’s somehow ok to continue this exploitation in the workplace, until that is, we use our collective strength to arrest this view.

The Labour Party manifesto addresses the dire, low pay that paid carers of children receive, it also commits to a £10 per hour minimum wage and improvement of collective bargaining rights, which are all of course needed to address low pay. However what it doesn’t fully address are the conditions which force many women into low paid jobs - a more radical approach to childcare and better employment legislation are necessary, but so to is addressing the role of women in the workplace being seen as an extension of their role in the home and therefore of less monetary value.

The manifesto, rightly commits to professionalising the role of early years children’s carers, this approach needs to be extended to all caring roles. The last Labour government introduced the Schools Support Staff Negotiating Body which aimed to offer schools support staff (overwhelmingly a female workforce) similar national bargaining rights to teachers (currently support staff pay and conditions are determined at a local level causing fragmentation) helping to professionalise the role. Jeremy Corbyn’s Labour have committed to re-introducing this, but to go a step further we could build a job evaluation system that values the role of affective labour. Knowing that my son feels loved and cared for when he goes to school is just as important to me as whether or not he can read and write. We could eventually consider similar arrangements for those that care for the elderly depending on the shape our social care system takes under a Labour government.

The role of domestic, catering or retail staff needs also to be elevated and their importance honoured, acknowledging and elevating these roles in the home as well as the workplace. Take for example a hospital, it is the cleaners and hostesses who are paid the least and are most poorly treated, yet they provide the foundation for the whole running of the hospital. A dirty hospital can’t keep a patient free from infection and good food supports recovery.

The recent heroic struggle of Serco workers at St. Barts hospitals shows what can be achieved through mass collective struggle, breaking down the legislative barriers that make this sort of action (currently) difficult to organise would make it easier for women to self organise against low pay.

These struggles will inevitably elevate both societies view of low paid women workers but more importantly will impact on the way that women workers view themselves and their own ability to capitalise on their collective strength (as previous mass action led by women has shown us) - the growth in the confidence of working class women, the disputes we will lead and the gains we will win will have a direct impact on the strength of our future demands.

But to ensure our collective strength is not diluted, the struggle in the workplace and the one in the home must be linked. Whether it is the Focus E15 Mums demanding better housing, the Ford Dagenham strikers demanding equal pay or the Dockers wives organising a rent strike in support of their striking husbands - there are concrete lessons we can learn. Our task now is to seize the opportunity that Corbynism presents us.

-

Silvia Federici, Revolution at Point Zero: Housework, Reproduction and Feminist Struggle, Oakland, PM Press, 2012, p. 16. ↩