The Very British Coup megagame provides much food for thought on how Labour should approach its present internal and external battles, and the bigger ones still to come.

The fledgling Labour government was in crisis. Manifesto commitments on housing, energy and media reform had all failed to become law, thwarted by unexpected opposition from within the cabinet. The government needed a solid legislative achievement to quell unease from the membership and the unions, but the faction-ridden party was divided on whether to prioritise scrapping Trident or pressing ahead with Brexit. MI5 were pulling strings in the shadows, the prime minister was under the thumb of the church, the Fabian Society was holding secret meetings with the army, and the Tory press was on the warpath. Labour was in power, but the establishment was still very much in control.

This was the situation roughly an hour into the Very British Coup ‘megagame’ at The World Transformed, as I and thirty-odd others played out a scenario inspired by Chris Mullin’s 1982 novel. If you haven’t read it, Mullin’s book is about a left-wing Labour prime minister struggling to impose his will on an uncooperative civil service and a divided parliamentary party – as thoroughly implausible as that may sound.

The game, like the book, is set in the late 1980s. While the parallels with today are obvious, the game’s creators, Jim Wallman of Stone Paper Scissors and Richard Barbrook of Digital Liberties, were keen to avoid hewing too closely to contemporary politics. Importantly, this is less a political simulation than an exercise in negotiation and coalition-building, and in approaching problems from alternative perspectives. A version set in 2020 would risk players becoming fixated on today’s factions and dividing lines, at the expense of the real point of A Very British Coup (indeed, for some older players, the battles of thirty years ago were still raw enough to provoke the odd caustic aside about some long-defunct groupuscule featured in the game).

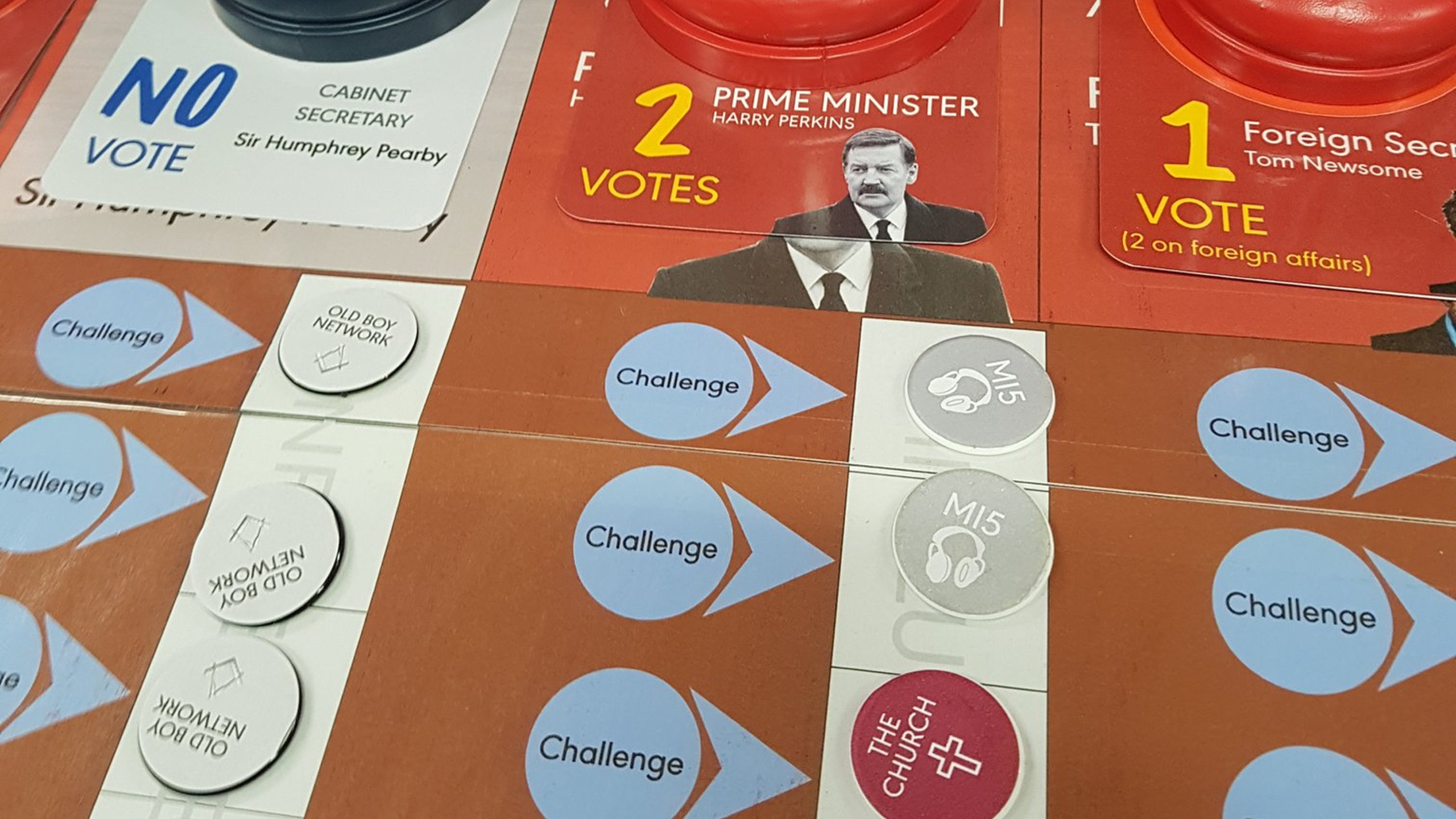

Most players belong to one of seven Labour factions, in teams of two or three, ranging from the hard left (Militant) to the right (the Fabians). The others take on the roles of the Conservative opposition and their establishment allies, such as the press, the security services, the Church of England and the military. Every turn, the Labour players try to get their preferred policies, all based on the party’s 1983 manifesto, adopted by the government and steered into law. The establishment players try to stop them, through a combination of parliamentary manoeuvring and backroom skulduggery. A Very British Coup is therefore both an internal battle for control of the Labour party, and an external one against the forces of reaction who oppose it.

Importantly for any game, A Very British Coup is a lot of fun. It is also fantastically complicated, especially for anyone not familiar with megagames. To start with, each policy has an impact score, a financial cost, and an outrage factor, the latter representing how much the right-wing press hates it. Labour players should try and pass high-impact policies while keeping an eye on spending and managing outrage ¬– there are dangerous consequences should either of these start to escalate out of control.

But it gets harder: each faction has particular policies that it is especially keen to adopt (the soft left Labour Co-ordinating Committee wants to boost spending on international aid) and others it would prefer to block (leaving NATO is a red line for the right-wing Labour Solidarity). In addition, each policy serves to appease one or more sections of the party’s base – the membership, the unions, and MPs – who will quickly get restive if their needs are neglected.

Finally, it is not enough for Labour factions to agree among themselves what policies to enact. They must also make sure enough of the cabinet is on board with their plans, and not swayed by some malign establishment influence. Factions can buy influence with ministers, but so can the establishment. If you take your eye off the cabinet table (literally a table, where cabinet members are represented by outsized chess pieces) a player representing the News Corp-like Fison Group might gain control of the Home Secretary, guaranteeing that for one turn at least she will vote not with the government but its opponents.

This complexity partially explains why in our game the government initially floundered as players struggled to get to grips with the rules. On at least one occasion, a policy failed to pass because one Labour faction forgot to vote for it. But some of our missteps were the result of tactical naivety. In the first round, an almighty internal policy row meant it was easy for the establishment team to focus on ‘turning’ ministers. By the time the dust had settled on our mini civil war, the Chancellor had been bought off by the Tories and the PM was in the pocket of the Church of England. Five of our first six policies were voted down. Jim Wallman, in his role as facilitator, informed us that the right-wing press was mocking our inaction, and the unions were losing faith in the parliamentary road to socialism.

Gradually, we began to understand how to make things happen. We began co-ordinating our strategies at the outset of every turn, negotiating within and across factions to ensure everyone in Labour put their resources to a mutually agreed end. Some factions learned to reach outside of the party to build alliances – the army would support the government’s employment bill, and in exchange the Fabians used their influence to ensure the government did not take the country out of NATO. As this demonstrates, the establishment is not some monolithic bloc either. In the same way, the press wouldn’t support us on much, but they did back our stance on the hunting ban, against the wishes of the Tories.

As the game progressed, we became aware that renationalisation was the establishment’s worst nightmare. We used the threat of state appropriation to make them acquiesce to less horrifying alternatives, such as investing in UK industry and empowering British workers. As the game wound up, we were on a roll and the establishment was on the run, and a room full of left-wing activists had learned that radical change was achievable once we set aside our differences and worked together.

But once again, it wasn’t quite that simple. Our attempts to pass our most radical policies, from abolishing Trident to reining in the security services, saw us outmanoeuvred by the establishment. Our major policy achievements, on industrial strategy and employment rights, were relatively mundane, and what’s more, they disproportionately favoured traditional social values and neoliberal economics (two further factors in the game). The factions that had racked up the most successes were the Fabians and Labour Solidarity, on the party’s right flank. One player summed up our overall results as “1950s Blairism.”

This is perhaps a subtler lesson of a Very British Coup. When the party was divided, radical policies were easily quashed by the establishment. Party unity was quickly established, but at the cost of radicalism. We learned to find a common ground and build a consensus, but did we compromise too much in doing so? Could the forces of reaction be defeated with a more ruthless approach? Or would that have provoked an even more drastic pushback from the establishment, as in Mullin’s novel?

Even a game as detailed as this one cannot, of course, be a perfect representation of the challenge that lies ahead. Important sources of power, like financial markets, extraparliamentary activism and the party membership, play only minor roles. And, of course, the parallels with the 1980s only take us so far, both in terms of power dynamics and salient political problems. But it undoubtedly provides much food for thought on how Labour should approach its present internal and external battles, and the bigger ones still to come.

I’d unhesitatingly recommend A Very British Coup as an office strategy away day, a CLP bridge-building exercise, or an alternative hen or stag do for people who really like politics. (It can be made more or less complex depending on the number of players, although at present it requires at least one expert facilitator to manage it.)

John McDonnell values wargames enough to have developed one (the notorious ‘run on the pound’ preparation) with Richard Barbrook. I would agree that there is a lot to be learned from anticipating the strategies and the compromises that might be required if Labour comes to power in 2022, or, with luck, much sooner. More than ever, we know what the stakes are. We cannot afford to let 1950s Blairism – or 2020s Blairism – be our future.