July was a volatile month in Guatemala, and this instability looks set to continue through August. Discontent had long been brewing over the government’s catastrophic mishandling of COVID.

The spark for these protests was the sudden dismissal of Juan Francisco Sandoval, the head of FECI (Special Prosecutor’s Office Against Impunity) - the country’s anti-corruption task force. He was leading an investigation into anomalies in the procurement of Sputnik V, and an incident involving the alleged delivering of bags of cash to Giammattei by an unidentified Russian businessmen. FECI had taken over from the UN-backed International Commission Against Impunity in Guatemala (known as CICIG), after it was terminated by the government in 2019. During its highly successful 12-year long operation, CICIG uncovered a string of corruption rings, including the notorious ‘La Linea’, which implicated the highest levels of government in 2015. As a direct result, former President Molina was jailed, and his government collapsed following some of the largest protests the country had ever seen.

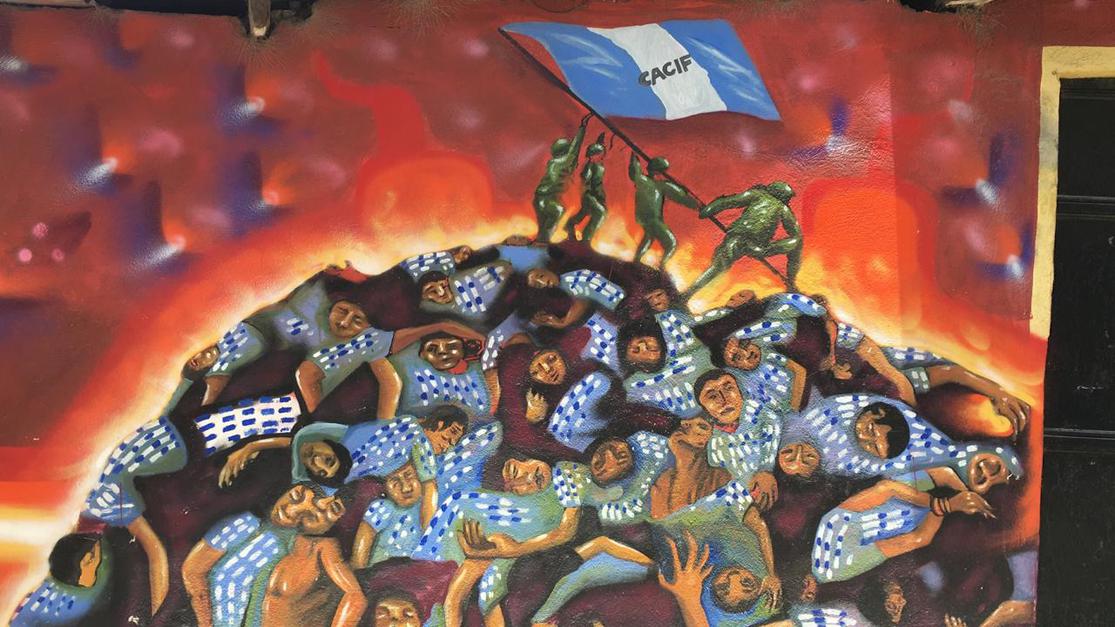

At this point, real change felt possible, and this opportunity was exploited by former comedian and political outsider, Jimmy Morales. He was carried to the presidency on a populist anti-corruption platform, with his slogan “not corrupt nor a thief”. Morales’ administration did initially seem to hold some promise, as Morales was not a member of the traditional business class, and he even publicly invited CICIG to investigate his party. Even so, concern was raised over his worrying ties to Guatemala’s military, and within little time, it also became clear that he was a puppet of the alliance of the oligarchy’s business interests, known as CACIF (the Coordinating Committee of Agricultural, Commercial, Industrial, and Financial Associations).

Anti-Cacif mural, photo credit Nancy González.

CACIF is the central component in what is known as the ‘Pacto de Corruptos’ (Pact of the Corrupt), that is, the close alignment of the country’s economic elites, military, politicians, drug cartels, and public authorities. This network has captured the state, and it largely controls the country’s media. When CICIG began investigating illegalities over Morales’ illicit campaign financing, CACIF closed ranks behind him. It mounted a counter-campaign against CICIG, claiming that its operation was a plot by the US and an ‘invasion of sovereignty’. Morales’ response itself was chillingly reminiscent of Guatemala’s past military dictatorships. When CICIG’s mandate expired in September 2019, he did not renew it. Under trumped up charges of ‘unconstitutionality’ and ‘abuse of authority’, CICIG’s operations were terminated, and Morales deployed tanks around CICIG’s offices in Guatemala City which some decried as a ‘soft coup’.

A similarly tense atmosphere hangs in the air today. Following his dismissal by Guatemala’s Attorney General last week, Juan Francisco Sandoval fled the country over fears for his life. Like CICIG, Sandoval too was dismissed under unjustified charges of ‘abuses of power’. The real reason however has to do with his effective direction of FECI as the country’s top anti-corruption prosecutor. He posed a threat to the interests of the small circle of criollo (European-descended) elites who have monopolised power since the Spanish Invasion. The frequency of protests against their corruption has increased since 2015, but to little effect. Breaking the cycle will take much more than the resignation of individual politicians, and this is because of how deeply systemic Guatemala’s problems are. The ‘Pacto de Corruptos’ is a hydra, and slaying it would require a refounding of the state, otherwise its heads will keep on regenerating. It is to this end that the current protests are focused.

This will be an uphill struggle. In the last couple of years, the ‘Pacto de Corruptos’ have consolidated their power, led an assault on the rule of law, and taken over Guatemala’s public institutions to neutralise dissent, evade justice and guarantee their impunity. They have already co-opted the Electoral Court, the Supreme Court of Justice, and the Constitutional Court, and they are using these public institutions to pursue and repress journalists, independent judges, and civil society. For example, in June of this year, a new Guatemalan Law on NGOs was passed which allows the government to close down NGOs which are deemed a ‘disturbance to public order’.

Although it is entering a new dangerous chapter, the criollo elite’s exploitative dominion over the country’s Indigenous majority has always been brutally defended. This was the underlying cause of the country’s 36-year armed conflict which only ended in 1996. During this period, Guatemala’s US-backed military committed acts of genocide against the country’s Indigenous Maya population, who represented the vast majority of the conflict’s 200,000 victims. Many hoped the signing of the Peace Accords in 1996 would signal an end to Guatemala’s entrenched racial hierarchy. Across Latin America, the 1990s was an optimistic decade for Indigenous peoples. In 1992, widespread protests erupted in response to celebrations of the quincentenary of Columbus’s ‘discovery’ of the Americas. This Indigenous mobilisation subsequently culminated in the advancement of Indigenous rights, with many Latin American governments (including Guatemala’s) ratifying the ILO-169 Convention. Yet while such gains eventually led to meaningful political openings for Indigenous peoples in countries like Ecuador and Bolivia, Guatemala has stagnated and even slid backwards.

Following the Peace Accords, international pressure obliged Guatemala’s criollo elites to grant some multicultural (but largely symbolic) recognitions to Indigenous people, yet they refused to concede any real economic or political power. 25 years after the Peace Accords this limited progress is reflected in some truly shocking statistics. 80% of Indigenous Guatemalans live in poverty, and they are three times as likely to live in extreme poverty than non-Indigenous Guatemalans. Their life expectancy is 13 years shorter, and 95% of those under the age of 18 who migrate are Indigenous. Indigenous peoples are also massively under-represented in Congress, where despite comprising over half of the population, they have managed to win only 13% of available seats. The internationally feted K’iche’ Nobel Peace Prize laureate, Rigoberta Menchú scraped just 3% of the vote when she ran for president in the 2007 and 2011 elections.

Guatemala and Bolivia are the only Latin American countries with Indigenous majorities, but they have followed widely different trajectories. While Guatemala’s colonial status quo remains intact, Bolivia’s Indigenous peoples have achieved meaningful political representation and an Indigenous president. While the position of Indigenous communities in Bolivia is by no means perfect, its plurinational state is still the envy of Guatemalans. Other countries with significant Indigenous minorities like Peru, Ecuador and Chile have also seen progress, or it at least stands on the immediate horizon following recent political events. Why then does Guatemala languish so far behind its southern neighbours?

One reason is the local rather than national scope of Guatemala’s Indigenous politics. The country has 22 different Indigenous groups, and they have tended to identify more strongly with their localities than a common Indigenous identity. The Maya movement which arose in the 1990s never led to the establishment of a major pro-Indigenous political party. Instead, Guatemala’s politics is characterised by numerous short-lived parties, and the small leftist pro-Indigenous parties have never achieved significant success at the ballot box. This is not to say no progress has been made, there has been a huge growth in Indigenous representation in municipal mayoralties. The political visibility of both an Indigenous peasant movement and Indigenous ancestral authorities has also increased tremendously. It is this grassroots mobilisation which is driving the current protests, and which also offers the best hope for Guatemala’s plurinational future.

The driving motivation of the ongoing protests can be traced back to 2015. It was in this year that demands for a Plurinational Constituent Assembly were first advanced on the national stage by various Mayan organisations. This demand was present, if not so prominent in the 2015 anti-corruption protests which toppled Molina’s government. In contrast, the protests today are explicitly framed around plurinational demands - the July 29th strike spread on social media under the hashtag ‘Paro Plurinacional’ (Plurinational Strike). Events in the preceding five years reveal why a Plurinational Constituent Assembly has risen to the top of the political agenda.

Guatemala has long been exploited for its natural resources, but it has entered a new wave of deadly extractivism. The mechanism of prior informed consultation (as guaranteed by the ILO-169 Convention) has proven unable to protect Guatemala’s poor and rural Indigenous communities from the extractivist assault of mining, agribusiness, and hydroelectric companies. Indigenous land defenders are being terrorised, criminalised and murdered by a complicit state, exacerbating a situation already dire due to the accelerating climate, health and economic crises (as evidenced by the desperate flow of migrants to the US). In the face of this repression, a prominent Defence of Territory (DOT) movement has arisen, along with the re-establishment of numerous ancestral authorities throughout the country. This common threat is uniting Guatemala’s diverse strands, and Indigenous dissatisfaction has begun to be channelled into a better organised national direction.

This new confidence could be discerned in the 2019 Presidential elections, where an Indigenous candidate – Thelma Cabrera shocked the establishment with her unexpected success. She came in fourth place with over 10% of the vote, the most successful Indigenous candidate ever. Even more remarkable, she achieved this with minimal campaign financing and in the face of a hostile media campaign directed by CACIF. Her party, the MLP (Movement for Peoples) was founded in 2018 by CODECA - a grassroots peasant organisation, which saw forming a legal political party as a means to better representing their interests and the struggle of their social movement. CODECA’s organisation follows the traditional political organisation of Indigenous communities, meeting in assemblies, and its ultimate horizon is the plurinational state. What’s notable in the ongoing protests is that unlike in previous years, CODECA and ancestral authorities have taken centre stage.

The accelerating co-optation of the state by the ‘Pacto de Corruptos’ has pushed Guatemala to the edge of no return, and the dismissal of Sandoval signalled the removal of one of the country’s few remaining fragile protections. This explains the urgency of the current protests. Although protesters are tired of corruption, particularly that involving the vaccine rollout, this is not just another anti-corruption protest. Guatemala is at breaking point, and protesters are concerned with the dangerous direction the country is taking. Corruption is a barrier to a functioning state, but freeing it from co-optation is only the first step.

The next stage will be creating a new political pact, a Plurinational Constituent Assembly which would transform Guatemala into a country where Guatemalans are able to live in dignity and take control over their own destiny. Similar to MAS’s constitutional assembly in Bolivia, this would likely involve decolonisation as an explicit goal. But unlike MAS, CODECA aspires to a different development model, and an end to extractive industries’ expropriation and dispossession. Their vision places food sovereignty and Indigenous territorial autonomy as a central concern, as well as parity for ancestral governance and law, and respect for Indigenous cosmovisions. Fleshing out these details and actually constructing a plurinational state would be a long and difficult process. Bridging the divisions between different social movements would present a major obstacle, as would gaining support from sceptical non-Indigenous Guatemalans. Nonetheless, the massive public outcry and mobilisation in response to recent events shows potential for a different Guatemala. This could finally be the plurinational moment Indigenous Guatemalans have been hoping for.