Arguably, we are at a critical sociohistorical juncture.

Arguably, we are at a critical sociohistorical juncture. The neoliberal conjugation of progressive liberalism with marketization is giving way to mutations that include both new forms of ethnonationalism, and new forms of socialism. Here, common sense has emerged as a central site of political contention and antagonism, with attempts to shut-down political possibility with “magic money trees” giving way to majority support to requisition local housing for victims of the Grenfell Tower atrocity, and Clive Lewis proclaiming that we should “burn neoliberalism, not people”. In an era that has often been characterized by the most hegemonic forms of neoliberal common sense in the sociopolitical formation governed by perpetual austerity, it seems that the ground is finally beginning to shift.

Of course, recent political and media responses to these shifts have largely operated as consensus defence mechanisms. Here, we witness still the upholding of neoliberal common sense that “austerity is not a political choice, but a financial necessity” against Jeremy Corbyn’s arguments to the contrary 1. And, expressions of popular democracy are doubly reprimanded – on the one hand for their supposed xenophobia and ethnonationalism – and for their utopian socialist imagination on the other. The sneering dismissal of the “racist working classes”, for example, enables us to see the ways in which political possibility is defined by what is taken to be empirical, or acceptable, whilst also employing sanctioning practices that aim to further embed and entrench that acceptability. The scope of the domain of the empirical, here, is typically limited to so-called moderate and centre viewpoints, which supposedly result from non-partisan and non-ideological managerial and pacificatory consensus, as determining the reality of both neoliberal socioeconomic formations, and political practice itself (as discussed by Williams). But, the increasingly obvious failure of this common sense over recent months is indicative of both the lie in which neoliberal centrism pretends to consensus and neutrality, and the reality of the massive-scale engineering project that it has required to maintain its hegemonic status through New Labourism to Austerity-Toryism and beyond.

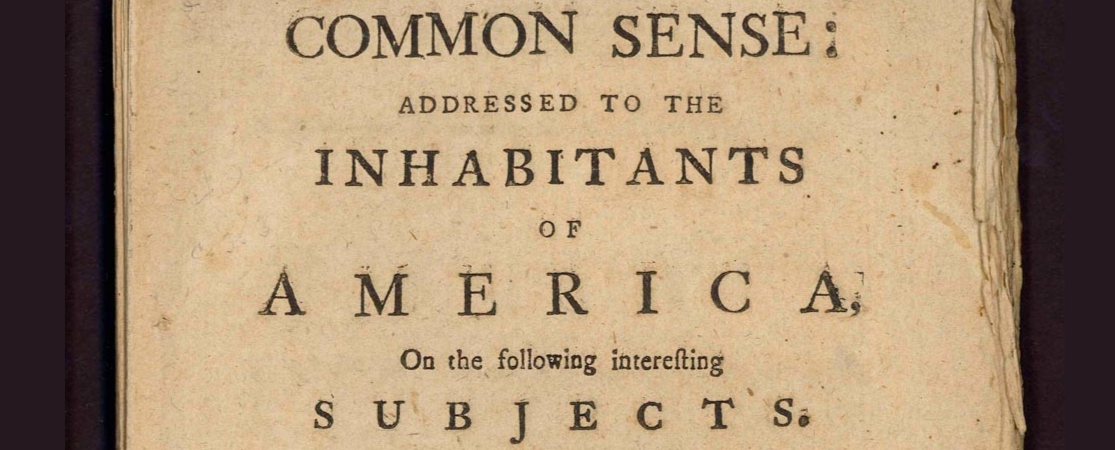

Common Sense Neoliberalism

In Common Sense Neoliberalism, Stuart Hall and Alan O’Shea discuss the ways in which media appeals to common sense are employed as a legitimation strategy that secures political standpoints 2. As they point out, the invocation of common sense is not simply an attempt to excavate popular opinion, but rather it also hopes to shape that opinion through the presumption that it is already shared. It is in this domain of common sense, therefore, that central political battles are to be fought. There are at least two dimensions to the way we can understand common sense in this context: the first being found “in the wild” so to speak, and the second, the discursively construed (and often constructed) mediatised appeals to common sense. It would be simple to think that it is a fissure between the two that has opened-up over recent months, where the political commentariat is simply out of touch with “real” common sense. But this would fail to grasp the mechanisms by which common sense operates, particularly regarding the way in which both forms are shaped by power, and potentially leads to the reified abuse of opinion polls, and the dangerous idea that a “new common sense” has already been reached.

As such, accounting for common sense is somewhat tricky, since its sedimentation and construction occurs at the level, not of discursive rules, but of assumptions, habits, and dispositions. Commonsense is not the sort of thing that can be discursively elaborated, being composed of attitudes that are open-ended, differential responses to each other and to contexts, emotions, and embodied actions. But, since this social background of norms shapes the meanings within which our lives are formed, it is also the central site in which our local interactions and contexts are tied to broader structures, practices, and sanctions. So, whilst neoliberal commonsense is deployed as a set of social constraints and configurations as if they are simply factual, it is more typically ingrained as sets of material practices. As Wendy Brown argues, with the neoliberal rise of competitive individualism, inequality becomes the norm, where we are at ongoing risk of failure, redundancy, and precarity, even concerning basic needs of food and shelter, whilst often not questioning our individual responsibility for these inequalities 3. In this context, common sense neoliberalism is often not visible at the level of discourse, but is grasped through its material and normative effects, many of which operate in the register of affect, mental health, and a permanent state of anxiety 4. As Ellie Mae O’Hagan put it, after speaking with employees of a recently bought-out carpet factory in Blackpool, “not one has said neoliberalism but that’s the system they’re describing and they know full well what it is because they’re living it” 5.

It is on this terrain in which common sense is continuously formed and reformed, as part-and-parcel with the material and embodied practices of our lives, where these are sculpted by the specific socioeconomic conditions in which we are inextricably located. It is also for this reason that common sense can neither be disparaged as misguided or intrinsically conservative, nor can it be upheld as a single monolithic and static “reality” outside of the conditions of power in which it is sculpted.

Neoliberalism, on this sort of story, cannot be adequately approached as if imposed as an ideological set of principles, but neither can it be fully captured in its objective and infrastructural forms – it is neither merely discursive nor merely material-determinative. Rather, the power of neoliberalism is that it is a massive-scale, and complex, engineering project, which has required multiple mutations over time, and constant reinforcement at all levels – from common sense to economic policy; from higher-education timetabling systems to detention-centres. This is largely not the result of an imposed, and top-down strategy, but rather of the constitution of a landscape of objective conditions in which the various incarnations of neoliberalism become more possible than others 6. In this way, this hegemonic neoliberalism has made and remade institutions and human subjects. Moreover, whilst coercion has been necessary, such as the carceral state in the UK and US, military intervention across the Middle East, confrontations between government and trade unions, and between police and protest movements and “riots”; on the whole, forceful sanctions are at the periphery of a largely coherent hegemonic project across social, political, economic, and cultural domains. Neoliberalism, then, in its current form captures a loose, complex set of mechanisms, practices, and norms, combining centrist governance with neoliberal managerialism and occluded state intervention in forging competition, which, taken together, would likely be disavowed by many of those espousing some of the norms upholding it.

So, neoliberal centrism can be understood to operate through forms of capillary power, as Foucault put it 7, which doesn’t require our assent, but is better considered in terms of the ways in which material and normative practices are shaped by a landscape of power that “consists in guiding the possibility of conduct” 8. Where neoliberal centrism emphasises consensus and equilibrium, the resultant entrenching of a local set of norms as setting the horizon for political discourse is always the result of complex processes producing relatively stable social forms through mostly harmonious interaction and conglomerate pressure. As such, it is necessary to consider the complex, and often non-discursive, ways in which commonsense is shaped, mobilized, and revised by considering the intersections of material and technical systems with social norms. For example, explicit appeals to common sense, to “hard-working families” or austerity as “tightening our belts” can be understood as part of more general frameworks of political articulation and power, which attempt to engineer our social norms and dispositions by imposing pressure to act along certain trajectories, and actualizing tendencies towards conservative social positions – in this sense, discourse has complex causal powers.

These sorts of appeals use explicit discourse to shape and embed the stability of social norms in the form of common sense, and thereby to sculpt the material practices and institutional forms in which it is expressed. In other words, our interests and meanings are never just “found” in common sense, as if making an invisible ideology visible, but neither are they simply imposed upon it. Rather, the consolidation of a specific alignment of interests from what is a loose and complex dispositional field, often involves the active reconstruction of those interests at the level of political discourse. Think of the processes by which, for example, the “benefit cheat” becomes seen as the enemy of the “hardworking family”, through the articulation of stereotypes across varying media, political articulation of our interests along this axis, and so on. Appeals to common sense are part of much wider processes requiring already entrenched meanings regarding, in this case, individual competitiveness, work, gender, and nationhood. These interests are then used to underpin substantial socio-political and material effects, looped into institutions and practices that serve to enact and enforce policy decisions, which then feed-back into media to further embed those social norms as if reality.

Reclaiming Common Sense; Resculpting Power

It is unsurprising, in this context, to find that there have been substantive attempts to maintain these systems of power (often by progressive liberals) in recent calls for the re-education of the young, in drawing attention to the supposed stupidity of the “common people”, and the mass moral condemnation of the supposedly racist working classes. There, the suggestion is that the people may not know what is best for them, and that governance requires institutionalized forms of rational expertise to ward off the “irrational crowd”. As such, the current crisis of common sense is understood as a problem of irrationality that can be put down to the simplistic viewpoints of those rooted in specific contexts that are incapable of gaining traction upon the complexity of neoliberal economics, society, and political decisions. It is of absolute import, that a left approach to common sense does not operate along similar lines, adopting (as it often has) a paternalistic advocation of “good sense” in critique of a duped working class. But, paradoxically perhaps, this sort of left paternalism exists alongside a tendency on the left to avoid looking like we are engaged in anything that could appear to be the manipulation of common sense. It is equally important that we do not shy away from the necessity to actively re-engineer common sense, to forge progressive practices, and to shift the current balance of power.

In distinction to these prior tendencies on the left, it seems that the conditions of the possibility for building new common senses cannot be rooted in ideology critique, or leftist intellectualism. Rather, they must be rooted in an experience of the effects and consequences of neoliberalism as a state of affairs, and material practices – in objective imbalances of power across the social landscape. Re-engineering common sense on the left is, therefore, part-and-parcel with building new social practices and forms. And, it is precisely here that we are already witnessing the re-articulation of common sense through the alignment of interests across new forms of social groupings that are far looser, and overlapping, than is suggested by both economic Marxism, and post-Marxist populism. These processes involve the construction of new ideological alignments, where these are operating beyond, and across, the fault-lines of class that have been traditionally identified by left movements. Any re-articulation of neoliberal socio-political forms will involve the construction of political alignments that work together to build shared interests, commitments, and meanings – we cannot deal with structural power by simply speaking from where we are situated in order that “we” are recognized. Rather, we need to actively construct social groups and standpoints that are always subject to current formations of structural power, even as they seek to uncover their conditions and transform them. Such alignments endeavor to coalesce common sense in a unity without unification, in order to construct and forge new norms, connections, and configurations of the social world 9.

So, this project of re-engineering common sense could not be simply a top-down campaign, but rather will need to involve the articulation of already existing dispositions and the construction of new spaces for social organisation. This is also to engage our desires, and to actualise these desires along the lines of progressive political forms of collective optimism and hope, as well as anger. For example, it is, to my mind, imperative that we do not give in to a regressive articulation of affect around freedom of movement and nationalism of the sort advocated by Blue Labour – that falls into a trap “implying that migration causes unhappiness by forcing people who are ‘unalike’ to live together”, as Sara Ahmed put it 10. Rather, we should continue to build new articulations of these feelings towards solidarity across workers, putting those who suffer most from the violence of the state and current common sense at the forefront. This is to actualise existing feelings, and experiences of the consequences of neoliberal decision-making, into political alignments that are neither determined by opposition to those conditions, nor concretise those emotions in a praxis of immediate and affective action. This also requires us to pay attention to the strategic reconstruction of our institutions and material processes to better scaffold and stabilize new norms, and practices. So, for example, we need to consider how to institutionalise more progressive social formations so that they can be scaled up, and used as platforms for further action.

As such, the project of re-engineering required to build new forms of power and common sense would be impossible without engaging with a broad and deep set of democratic activities. This is to absolutely refute the idea that the new forms of democratic action that we are witnessing from Momentum to Black Lives Matter are, in fact, anti-democratic attempts at incursion upon politics proper. Equally, we need to actively reconceive our democratic institutions, and to build new ones, which reach into our everyday lived realities. This requires that, on the left, we have conversations about collective rationality and reasoning together. For example, we need to ensure that our democratic practices both include those voices that have so often been excluded, and also involve practices and expressions that have been routinely discounted as “irrational”, “unreasonable”, or “emotional” (see also Marie).

In this regard, the left, as much as anywhere else, needs to face-up to its implication in structural neoliberalism, and to actively attempt to undo it in every setting. It is a well-trodden reality that systems of oppression tend to work their way back in to organisations on the left. This has often been dealt with by an emphasis on consensus, which occludes the dynamics of power and exclusion that operates in face-to-face decision making, and is frequently coupled with the obviation of organisation and hierarchy, which leads to a tyranny of structurelessness, entrenching those forms of power. Instead, radically democratic processes should not be considered absent of power, but rather to work within, and on, a landscape of power in order to reshape it towards local and generic structural justices. So, rather than think of democratic reasoning as just the joint assessment and comparison of claims made by individuals on a supposedly equal footing, we should consider the ways in which we collectively construct and articulate claims, reasons, and norms in these situations. This will require us to consider how those situations are already structured, along the lines of a landscape distributed with dispositions, habits, resources, limitations, and where our capacity to re-articulate that landscape will also depend upon our positions within it. Making this landscape visible, so refusing to allow those local sets of norms to become the horizon for discourse within our social groups and institutions, and working to revise them, is therefore integral to our democratic activity.

In light of this, and since the contemporary left intersects across several social settings and material structures, a new socialist movement may be understood as attempting to actualise and alter our dispositions and capacities to act along certain trajectories: as a collective direction of travel, rather than a unified set of beliefs. This is to shape, together, new forms of common sense in ways that we are already seeing – resculpting political possibility by beginning to make claims and positions seem more possible than others, building towards new forms of collective activity that move beyond neoliberal acceptability, and creating new social “realities”. Much is yet to be done, but these alignments are already beginning to pool together as a complex and emergent movement, in which the domain of politics is not limited to Westminster, but is concerned with transformation across all of our forms of life, for the better.

-

Martin Daubney on Sky Sunrise, 28th June 2017 at 8.40am. ↩

-

Stuart Hall and Alan O’Shea (2013). “Common-sense neoliberalism”. Soundings 55: Values as commodities. ↩

-

Wendy Brown (2015). Undoing the Demos. MIT Press. ↩

-

See Mark Fisher’s excellent discussion of these effects in e.g. his (2009), Capitalist Realism: Is there no alternative?. Zero Books. ↩

-

@MissEllieMae, July 21st (2017), 5.06am. ↩

-

See Alex Williams (2015), “Complexity & Hegemony: Technical Politics in an Age of Uncertainty.” University of East London. http://roar.uel.ac.uk/4773/. ↩

-

Michel Foucault (1980). Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writings, 1972-1977. Pantheon. ↩

-

Michel Foucault (1982). “The Subject and Power.” Critical Inquiry 8 (4): 777–795, p.789. ↩

-

On political articulation, see Stuart Hall (1985). “Signification, Representation, Ideology: Althusser and the Post‐structuralist Debates.” Critical Studies in Media Communication, 2 (2): 91–114. This understanding of articulation differs from the one given by Laclau and Mouffe since, re-articulation does not invoke a populist “we” whose identity is formed in opposition to the exclusionary power of liberal democracy, but rather invokes a complex, and intersecting set of social formations. See Laclau, Ernesto, and Chantal Mouffe (1985). Hegemony and Socialist Strategy: Towards a Radical Democratic Politics. Verso Books. ↩

-

Sara Ahmed (2008). The Politics of Good Feeling. Australasian Journal of Critical Race and Whiteness Studies, 4(1). ↩