Keir Starmer looks set to win & Rebecca Long-Bailey’s campaign has stuttered, but the left must not pass up a historic opportunity to transform the party, & resist the inevitable attempts to do so from the right.

On the basis of polling and CLP nominations, Keir Starmer is the clear favourite to be the next leader of the Labour Party. It is easy to understand how this has come about—Starmer had begun his campaign almost before the general election was over, and fairly obviously had a campaign ready to launch at 10.01pm on election night, while the “continuity Corbyn” (a euphemism for ‘most left wing’) candidate Rebecca Long-Bailey didn’t decide to stand until the last minute, and had not been attempting to position herself as a potential successor in the way that Starmer, Emily Thornberry, Lisa Nandy and Jess Phillips had. Over the past year or so, Starmer and Thornberry have been up and down the country rubbing shoulders with Labour members, whereas Nandy appeared to have a season ticket to Andrew Neil’s BBC programme and the avaricious Phillips has seldom been out of the Murdoch press. Long-Bailey, on the other hand, spent much of the past three years holed up with unionists and green activists, developing her Green Industrial Revolution policy.

Of those who made it onto the final ballot, Starmer stands out as the most popular across Labour’s various factions and traditions. Much has been made of Starmer’s “loyalty” to Corbyn, despite him having resigned during the ‘Chicken Coup’ of 2016, and subsequently having supported the almost inconceivably incompetent and gauche Owen Smith in the ensuing leadership contest, reputedly just because everyone else was. As incoherent as it is to praise Starmer’s loyalty to the Corbyn project, there is a grain of good sense in backing him as the “unity candidate”; Starmer’s willingness to serve under Corbyn as shadow Brexit secretary endeared him to many on the left. His aforementioned resignation won him the respect of the Blairites and Old Right. He is, therefore, relatively well-liked across most of the party. However, the idea—pushed hard by Starmer himself—that he can bring about “party unity”, is either entirely fanciful naivety or disingenuous over-promising.

If Starmer wins, the Labour ‘moderates’—the Blairites and the Old Right—will use everything in their arsenal to drag him to the right, despite knowing that they can’t completely break with Corbynism at this stage. After almost five years of Labour being led by a socialist, we have a pretty good idea of how the right will operate if they don’t get their way: leaks, anonymous briefings, resignations, whispers of a split, creation of wedge issues, and smears. This all happened despite Jeremy Corbyn displaying way more generosity and willingness to compromise than Blair ever did. Yet it predates Corbyn’s time as leader. Ed Miliband—with whom Starmer seems to be of a piece, politically—spent much of his stint as leader being corralled, bullied, browbeaten, and blackmailed by the right of the party. This culminated in the infamously uninspiring 2015 manifesto—referred to internally as “austerity-lite”—which was barely distinguishable from that of the Conservative Party, contained almost no progressive policies, and was memorable largely for a racist mug and the ludicrous “Edstone”. Miliband resigned following his 2015 election hammering, and some who know him have said that he confided that he then suffered “an existential crisis”. The PLP may have failed in its stated aim to “break Jeremy Corbyn as a man”, but it seems they may, temporarily at least, have succeeded in breaking the endlessly pleasant and well-intentioned younger Miliband brother. In the wake of his defeat, the received wisdom from the sages of Butskellism (the rather ungainly term for the tradition that rivalled the Bevanites) was that Miliband had been thumped in the general election because he was too left wing, rather than because he and his advisors were too craven or mean-spirited to offer voters any meaningful improvement to their material circumstances.

Starmer still refers to himself as a socialist (although it seems likely that his definition would be closer to that of Anthony Crosland than that of Tony Benn), and is no more the Labour right’s creature than Miliband was, so there is no question of them feeling any sense of loyalty to him. Reputedly active in a Trotskyist group during the 1980s (when, don’t forget, Neil Kinnock was gleefully kicking Trotskyists out of the party), Starmer seems now to be significantly closer to the centre than Corbyn, John McDonnell, or his fellow leadership candidate Rebecca Long-Bailey. He is, however, to the left of Stella Creasy, who suggested abolishing manifestos in favour of letting technocratic, unaccountable no-marks like her do whatever they want with the levers of the state. He’s to the left of Wes Streeting, whose most sincerely held ideological position seems to be that his former employer, McDonalds, should be able to hawk burgers at the Labour Party conference. And he’s to the left of Stephen Kinnock, who was beginning an abortive leadership pitch seemingly based on the tenets of Vichy France when he should have been trying to help Labour win the 2017 general election. These members of the PLP—and many, many others—are not agnostic about socialism. They are actively opposed and openly hostile to it, and will not help Starmer campaign for or implement socialist policies. Having rejected open selection, Starmer has rejected the only realistic means of disciplining or even managing the right. He will have to find another way of dealing with them.

How much support Starmer can expect from the PLP’s coalition of Blairite wannabe technocrats and Old Right malcontents and bigots will be determined by how much of Corbynism’s twitching corpse he is willing to slice up and feed to the pigs. If he isn’t prepared to concede that market forces and foreign military interventions are the only way win the next election, the ‘moderates’ will deploy their now-familiar tactics.

Once Starmer becomes leader, between now and the next general election he will face huge pressure to marginalise or expel members and organisations from the left. He will also be pressured into adopting positions that will cause members on the left to leave voluntarily. The point of this will be to reshape the membership with an eye on the next leadership election. Yet, all the while, they will be making entreaties to party unity; they will even claim that expulsions are in the name of party unity. This is a convenient cover, especially as it resonates with a heartfelt desire for party unity on the left. The outcome of the EHRC investigation will likely be used as an excuse to purge left wing members, remove Jennie Formby as General Secretary, and hire a Labour right figure like Tom Watson to replace her. Starmer’s apparent interest in the BDS campaign (as recently as 2015) hasn’t yet been mentioned. If he doesn’t do as he’s told, it will be—and we know how that will be covered by the media.

The right won’t stop there. They will demand that Labour’s Community Organising Unit—the bottom-up potential of which threatens the power, status, and self-image of MPs, councillors and various party bureaucrats—is junked. This would be near-suicidal, and counter-intuitive when even the Blue Labour-friendly Lisa Nandy—a member, product and representative of the political class—accepts the need for Labour to re-connect with the communities that once formed the party’s bedrock. The COU represents a shift towards the kind of horizontalism and ‘people power’ that the Labour right has always resisted, not only because of the aforementioned jealousy with which they tend to guard the bureaucratic power they have built up in councils and regional party offices over decades, but also because of their patrician and pessimistic attitude to the working class. Even if the COU was retained, it would be expected to be operated from the top down and helmed by a professional-political class ‘moderate’ with absolutely no understanding of food poverty, rent poverty, or precarious employment.

Starmer has already reached out to Labour councillors and promised them greater influence on the NEC. Trying to appease thin-skinned councillors, whose aversion to democratic oversight will see them ask to be insulated from it, would mean an attack on democracy at CLP level and sanctions for anyone who criticises the often unpopular, sometimes outright cruel policies implemented by some Labour councils. By ingratiating himself with anti-socialist MPs, councillors and bureaucrats, Starmer risks turning the party inwards, speaking and listening to the bourgeois and pseudo-technocratic who, despite typically spending as little time around working class people as possible, ventriloquise the working class to their own ends. What is needed is for us to turn outwards to the class itself—including the membership.

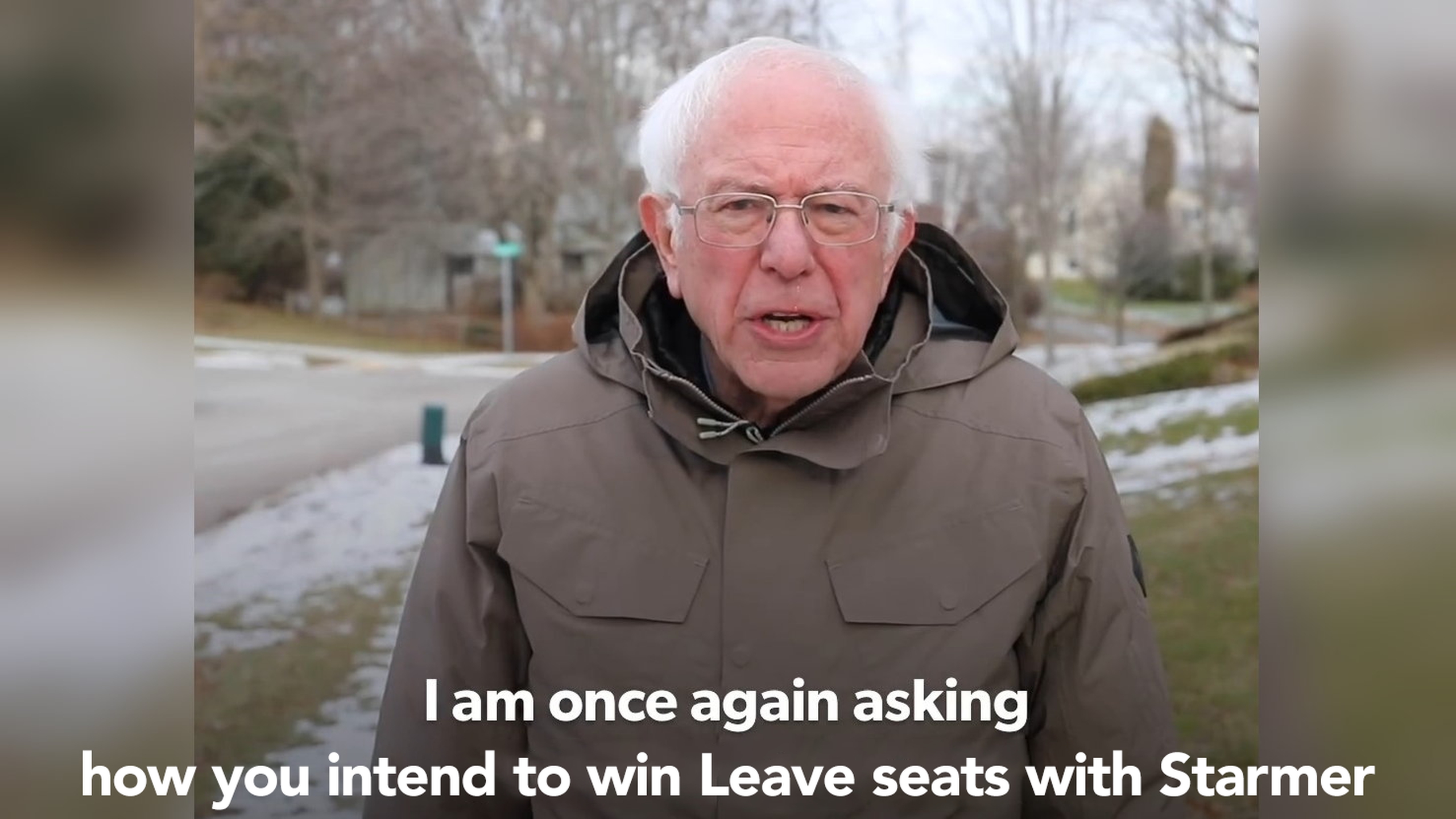

Most pressingly, Starmer has reached his present status as the darling of the liberal media and the centre left via his positioning as the arch-Remainer. His speech at the 2018 party conference—eulogised in almost orgasmic language by the Guardian’s Martin Kettle—featured the MP for Holborn assuring the floor, with a voice like a woodwind instrument, that “nobody is ruling out Remain!”. This Europhile self-indulgence may, in retrospect, have been the moment Starmer’s leadership bid began. It may also have been the moment that Labour’s support in Leave-voting post-industrial areas- which had been decaying for years- finally collapsed. The most concerning thing about Starmer is not that he may have held controversial or divisive positions, but that he and his backers have totally ignored requests to explain how he will rebut the inevitable accusations and smears. He hasn’t explained what his strategy will be for winning back Leave seats, having been the architect of a policy that Leave voters felt was an attempt to disenfranchise them. Much has been written about Starmer’s ‘electability’ (Tom Gann has unpacked the amorphousness and nebulousness of this term on his Medium blog), yet none of his supporters—not Zoe Williams, not Paul Mason—have even tried to explain why the former Director of Public Prosecutions will be acceptable to Leave voters in former ‘Red Wall’ seats, who will be encouraged to see Starmer as the absolute living embodiment of the condescending, anti-democratic, elitist, dishonourable, Britain-hating Remoaner—assuming he isn’t seen that way already. The idea that this won’t happen is surely a fantasy. If he wins, Starmer will assume the status previously held by Corbyn and Miliband as the most left wing politician in the public eye, and so, unless Starmer follows Blair in giving Rupert Murdoch right of veto over his entire programme, the attacks will begin. Starmer, and the loyal Labour activists knocking on doors in his name, would be pilloried as enemies of Britain and of democracy.

Presenting media hostility to progressive politics as a factor in electoral decision-making may seem defeatist, but it isn’t. New Socialist is just one of a number of alternative left-wing media resources. Long-Bailey launching her leadership bid via Tribune was a sign that she understands the necessity of building left media, instead of caving in and allowing Labour’s direction of travel to be determined by the sordid whims of a scabrous old toad like Murdoch and his stable of white supremacists—or, for that matter, the confounded, floundering liberal media and the whimpering, simpering BBC. Unlike Starmer, Long-Bailey is supportive of calls to democratise the Corporation, which at this point has all the credibility and journalistic integrity of “Mean” Gene Okerlund, the moustachioed ‘reporter’ employed by wrestling promoters to ask questions of grapplers that allowed them to advertise their matches.

This is not to say it would be impossible for Starmer to win an election. He would likely win back a number of liberal Remainers. It is difficult, however, to see how Leave seats could be won back without the party embedding itself in the lives of ordinary people through involvement with deep, solidarity-building, community organising that might involve micro-level attempts at municipal socialism, and similar efforts in workplaces. Long-Bailey has reaffirmed her support for industrial action and community organising—something to which Starmer has not committed.

Starmer’s key pledge—the imposition of party unity—is a promise that will be impossible to keep. The desire for the party to unite—or just for all the nastiness to stop—is perfectly understandable. Everyone should want this. No one has enjoyed the internecine spite and playground bullying of the last few years. Yet here is a point that must be made and accepted, no matter how sentimental we may be about the Labour Party: unity—meaning, literally, oneness— in a political party containing both Marxists and devout believers in the free market, is impossible. The only way to bring about unity would be for one of the disparate tendencies to exit the Party, voluntarily or otherwise. This is not an entreaty to that effect; rather, it is a call not for unity, but for solidarity—for a coalition of actors who share an interest but not an identity to work together. Yet before even this can be considered possible, Labour moderates must say what they are for. Over the last two Parliaments, the Labour right has defined itself almost exclusively through its opposition to Corbyn. For a rapprochement with the left to be plausible, the right must do more than actively opposing the left and making occasional gestures at opposing the Conservative Party. It must outline exactly how it wants society to be organised. Only then can we decide whether this vision is reconcilable with that of the radical left.

When Tom Watson set up the Future Britain Group- a coalition of “TBs [MPs who are adherents of Tony Blair] and GBs [those closer to Gordon Brown]”, it seemed like we might get at least an inkling of what kind of future these Corbynsceptic “moderates” might envisage, yet nothing ever came of it. In all his time as Shadow Secretary for Media and Culture, Watson’s only policy suggestion involved cracking down on football fans priced out of stadia and pay TV from watching matches on illegal streams.

Most commonly, ‘moderates’ will identify their politics as that of social democracy, but this is a slippery, changeable term. Aneurin Bevan described himself as a social democrat, but the pugilistic ex miner who legislated the NHS into being and described the Conservative Party as “lower than vermin” would surely have had little time for the prominent voices on the Labour right who started the “care not car parks” Twitter hashtag and who bristle at the uncouthness of those of us who choose not to be friends with Tories. What does it now mean to be a social democrat? Prior to 1917 it effectively meant a Marxist, then, during Bevan’s pomp, it meant a Keynesian. Now, if we have to hazard a guess, it perhaps means the following:

- A belief in a market-driven economy with a large but increasingly financialised state.

- A lukewarm nationalism that often lapses into what looks a lot like xenophobia.

- Superficial accommodations to liberation politics (pro-feminist, pro-choice, pro-gay rights, anti-racist) that veil a loitering social conservatism, within which often festers a latent Islamophobia, transphobia and a Victorian sternness towards asylum seeking and rough sleeping.

- A belief in Atlanticism, a belief in the necessity for Britain to possess, manufacture and sell nuclear weapons, a belief in the need for Britain to be complicit in foreign interventions that aid the spread of liberal capitalism, and a belief that Britain must help defend the state of Israel no matter what it does.

If this is inaccurate, I hope I can be forgiven on the basis of the aforementioned radio silence regarding the beliefs of this political formation. I encourage any self-identifying social democrat reading to put me right. Historically speaking, though, and perhaps putting ideology aside, the Labour right have never really stopped believing that elections are won by making concessions to the most base of nativist instincts and by embracing the ‘aspiration’ offered by the free market, and the soft left is still yet to let go of the notion that if one of their own—like Miliband, like Starmer, and like Neil Kinnock before them—stands on a platform of right reformism, they can win a general election for Labour. As Bryan Gould, Labour’s former Shadow Secretary of State for Trade and Industry, said during the Blair years:

The position taken by Labour’s leader’s in the late 80s and early 90s was a position of surrender, or an acknowledgement that we had lost the argument. That Thatcherite hegemony had been established, that we could only accommodate. We couldn’t change it fundamentally.

The Labour right are hoping it is 1983 again. This is why they are so desperate to ridicule Corbyn’s claim that Labour “won the argument”, despite Downing Street’s in-house, Yellow Bastard-like galaxy brain Dominic Cummings nationalising rail and getting ready to stuff gold into the mouths of borrowed voters in post-industrial towns. The fact is that that soft left leaders dancing to a tune borrowed from Margaret Thatcher or David Cameron never got as many votes as the socialist, anti-imperialist Corbyn, standing on a platform of social democracy, did in 2019, let alone 2017.

There’s no material disadvantage to the Labour Right explaining its politics—if they say they’re free market warmongers and they eventually get control of the party, most on the left will leave, and that is what they want. Yet they seem determined to remain the hatred that dares not speak its name. Which brings us to its organisational base, Labour First.

At CLP level, Labour First pretends it doesn’t exist, which is ironic given that this was also the strategy of their sworn enemies of the 80s, the Trotskyist group Militant. Despite being a faction, they criticise factionalism, with members presenting themselves as merely nice, normal comrades who are loyal to the Party, as opposed to the ‘party within a party’, Momentum, which they characterise as being full of ‘Trots’ who have no interest in winning elections. Almost the opposite is true. Over the last few years, the only elections, be they external or internal, that Labour First have been interested in winning were those involving their members. Anyone who wants to stand against a Corbynsceptic candidate is attacked and told they should “focus on fighting the Tories”, which is also what they say when open selection is mentioned. We all wish we could focus on fighting the Tories. In practice though, some on the Labour right will not be primarily anti-Tory for as long as there is a socialist leading the party.

Labour First are so used to being able to hide in plain sight that they could scarcely be less subtle in telegraphing their intentions, with the faction’s chair Luke Akehurst tweeting “I would give my fucking right arm for another [Neil] Kinnock”, before throwing a tantrum about a suggestion from New Socialist-endorsed deputy leadership candidate Dawn Butler that PLP members who undermine the next leader should be disciplined. This is because, in Akehurst’s mind, and the hive mind of his fellow travellers, it is they who should be imposing discipline. Older readers might think back to the period between the 1987 and 1992 general elections and remember the rather doleful spectacle of the ebullient, extrovert, working class Welshman Kinnock—by this time party leader in name only—looking subdued and sombre in an undertaker’s suit while his pallbearers on the right of the party did the talking.

Kinnock’s enduring popularity with the right should be instructive to members. The right talk a lot about the imperative to win, but have granted legendary status to a two-time loser. Why? Because he scorched the earth so completely that the left was defeated for a generation or more. The right’s win-at-all-costs mentality is focused on control of the party, not control of the state. This brings us to one of the most extraordinary aspects of Corbyn’s time as leader, which has barely been remarked upon: had the right helped Corbyn to win a general election, the composition of the PLP would have seen Corbyn and McDonnell almost completely in hock to the right. They would have been able to dilute the programme to their own taste, particularly as Corbyn’s entirely creditable instinct has always been to make compromises for the sake of the vulnerable. Perhaps the right’s belief that Corbyn was an illegitimate actor was so devout that they rejected any prospect of collaboration with him outright. It seems just as likely, though, that soft power is not enough to satisfy them—ultimately they want to be seen to be in charge.

So Starmer’s promise of unity is a hollow one. But is unity even desirable? I’d argue that it isn’t. What we really need, and what Labour members should be able to hope for, is solidarity. Imposed unity suppresses difference and creativity. Solidarity gives us a means of collective struggle in pursuit of shared interests and a common purpose. This can’t be imposed from above, by Starmer or by anyone else. Solidarity is democratic. This is why the Labour Party must be democratic. If we know that all our MPs are working towards a common goal, we will have solidarity, and the biting and barking will necessarily stop. With open selection, purely self-interested actors will no longer be able to sabotage, or threaten to sabotage, our electoral chances for their own ends. The Labour right would not be purged, but would have to prove that it cares about winning elections rather than simply protecting its privileges and insulating its comfortably-off members and supporters from a programme that might include tax rises or a drop in the value of their houses. This insinuation may be harsh. If it is, let them prove it.

Before any lasting rapprochement can be considered remotely feasible, moderates must first say what it is they want. With renewed talk of the need for a ‘progressive alliance’, we will hear once again that “we’ve already got a progressive alliance: it’s called the Labour Party”. But we can’t reasonably expect voters to trust such a coalition if we can’t trust it ourselves, and there can be no trust without an explicit rendering of the intentions of everyone involved.

With open selection on the table, we have an opportunity to create a Labour Party that is truly representative of its members. The critique of this has always been that Labour members are not representative of wider society, yet this is all too easily countered by the hard-to-disprove assertion that the PLP is even less so. And even if one subscribes to the democratically dubious, Burkean notion that MPs are expert representatives, it is unserious to argue that the absurd Neil Coyle—with his dank late night tweets directed at imagined foes—is an expert on anything. The moribund leadership contest is causing some comrades to remark on how poor the field is, which is hardly surprising given Corbynism’s failure to break sufficiently with a culture that allows careerist nonentities with no connection to the constituencies they represent to be selected as Parliamentary candidates. If we want better candidates, we need to open up the party. It must be open selection, which means it must be Long-Bailey. The MP for Salford is a conciliatory, unpretentious, and increasingly likeable politician who, as has been remarked upon by Joe Kennedy, is exactly the sort of leader the soft left commentariat would be casting long, lingering, envious gazes at were she leader of an equivalent party abroad, or of the Green or SNP parties closer to home.

Long-Bailey has, through a combination of a shortage of time and an over-abundance of innate decency and loyalty, been manoeuvred into appearing inconsistent and injudicious at times during her hastily assembled campaign, but her integral role in the Alternative Models of Ownership and Green Industrial Revolution strategies show that this is a working class woman (for a time, the moderates now gung-ho for Starmer acted as though it was axiomatic that the next leader should be a woman) who is more than capable of acting in concert with a volatile and seismic political moment. Meanwhile Starmer maintains that his divisive and damaging Brexit strategy was “the right policy”. It is through strategies like the Green Industrial Revolution that Labour can prove, once and for all, that the cause of labour truly is the hope of the world. It is right that Long-Bailey, as its architect, should also be its champion, especially with Starmer’s mortifying refusal to commit to a timetable on decarbonisation. Starmer’s lack of a political backbone is exactly the sort of thing that cultivates public mistrust in a politician. It’s part of what ruined Kinnock, and even, to some extent, Corbyn, whose image as an anti-establishment insurgent was destroyed by the sight of a supposed EU-sceptic gaming Parliament in order to frustrate Britain’s departure from the EU.

Starmer is supposedly renowned in the legal profession for making impregnable arguments, but a silver tongue and carefully-coiffed silver hair do not equate to a silver bullet. He may very well be as decent a person as his supporters believe him to be. But how many more decent people must we see destroyed by the media, and even by members of our own party, before we address the roots of our problems? The reckless wrecking of the Labour right won’t stop just because Starmer is leader. They will see his stewardship as an opportunity. The only way to bring about harmony in the Labour Party is to introduce open selection. The only way to prevent Labour leaders being destroyed by the media is to build our own. And the only way to heal the wounds of Brexit in our communities is to be in those communities, in their workplaces, organising, persuading, pressing, coddling and convincing people that instead of blaming everything on immigration, they need to join a union, organise with—not against—one another, and vote Labour.