Asad Haider’s ‘Mistaken Identity’ is a convincing defence of coalitions and class struggle, but makes an all-too-subtle argument against political pessimism.

Asad Haider took three risks while writing Mistaken Identity. Firstly, the book is short: at 144 pages, many of its arguments must necessarily remain implicit. Secondly, and in contrast with many contributions to Marxist theory, Haider draws generously on his personal experiences, both from childhood, and his activism, to inform his analysis of contemporary political struggles around identity. Thirdly, Haider explicitly rejects what he calls the ‘holy trinity’ approach of race/gender/class only being spoken of in one breath, instead producing a collection of essays which he tells us will focus solely on race.

Between these three decisions, Mistaken Identity has caused a considerable degree of confusion, along with inevitable criticisms about the ground it failed to cover. While a string of extended arguments concerning identity had previously been advanced by Haider and his collective Viewpoint Magazine (as we will see), the approach taken here in Mistaken Identity was purposefully minimalist — apparently frustratingly so to some readers. Reviews of the book have often focused on those glaring omissions that a more comprehensive work would surely have addressed. These alleged weaknesses tend to reflect the priorities of the reviewer, rather than revealing much about Mistaken Identity: from the International Communist Tendency’s complaint that Mistaken Identity includes no thorough account of Stalinism, to a review in the new Commune Magazine which criticises it for not engaging with the work of Frantz Fanon, to a peculiar Jacobin review which charged Haider with not paying due attention to the administration of LB Johnson. Another notable absence, I would add, is a detailed treatment of the US Democratic Party’s determined efforts to co-opt the politics of identity.

The book has also been criticised for lacking even a brief historical account of ‘class reductionist’ Marxism, which has more recently begun to style itself as ‘anti-identitarian’. Those advancing social democratic arguments have often made a case for downplaying anti-racist activism as a particular focus, in favour of generic anti-poverty policies: focusing on providing universal healthcare and other welfare state provisions, it is commonly argued, would do more to improve the living conditions of ethnic minorities than more ‘divisive’ approaches to political action (such as anti-prison campaigning, or protests against police violence). These arguments have been prominent in US left discourses at least since the primary campaign of Bernie Sanders; but Mistaken Identity does not offer any detailed response to them. As such, Haider has been charged with advancing a one-sided opposition to the politics of identity, without a grasp of the conditions out of which so-called ‘identitarian’ politics responsively arise. Criticism of ‘workerist’ positions is not, however, entirely absent from the book. Recounting his early encounters with ‘class first’ Marxists in Santa Cruz, and comparing them unfavourably to the Black Panthers, Haider writes:

I came into contact with many more Marxists, and sometimes found myself arguing with the white ones who thought that anti-imperialism and even antiracism were outmoded [and] little more than a slogan, because the real problems of people of color could be explained by the contradictions of the economic base.

I couldn’t relate to this and couldn’t really see what it had to do with Marxism. I had not encountered anything to convince me to reject [Huey] Newton’s definition of socialism as “the people in power,” and it seemed to me that when people organized themselves to resist imperialist and racist oppression, they were working toward building that power, even if the uncertainties of history meant that their efforts often fell short.

While clearly operating from within a different tradition, Haider today seems to have nothing to say to this flavour of leftist. This silence is characteristic: Haider has been similarly evasive when challenged by revolutionaries keen to promote more purportedly ‘universalist’ politics than his own. For example, an in-depth response to Haider’s views on the Enlightenment by Harrison Fluss and Landon Firm drew no further reply. This approach of non-engagement is undoubtedly a time-efficient way for Haider to avoid engaging with those he deems hopeless. It also reflects a certain privilege of position earned by Haider having founded Viewpoint Magazine, a collective dedicated to both continually developing new revolutionary perspectives, and publishing previously obscure historical material. Originally intended as a vehicle for interventions into the Occupy movement, Viewpoint has long since transcended that rowdy moment, and come to serve as both an online archive of bygone revolutionary eras, and a platform for speculative research. Although always international in focus (and, now, in membership too), the Viewpoint collective can also be seen as a distinctive outgrowth of the ‘West Coast Communist’ scene—a loose and fractious seriality of troublemakers, just as likely to interpret their immediate conditions through close readings of Marx as to attempt intense engagement with the more poetical thinkers against whom most old-school Leninist groups would caution their cadre. This blend of energies, drawn both from small-scale study circles dedicated to previously obscure ultraleft texts, and from informal networks of camaraderie built up during the intense street campaigning of Occupy Oakland, has formed a milieu equally prone to fussy re-readings of bygone debates between reds as to freewheeling intellectual cosmopolitanism in their analysis of contemporary conditions (or, as Haider would usually phrase it, the ‘conjuncture’). Approaches in these circles roam seamlessly from the scholastic to the insurrectionary, informed as much by reading groups as riots. Viewpoint displays both faces of this contradictory vigour in full force, albeit with a slant towards anti-capitalist organisation (broadly defined), and away from nihilism.

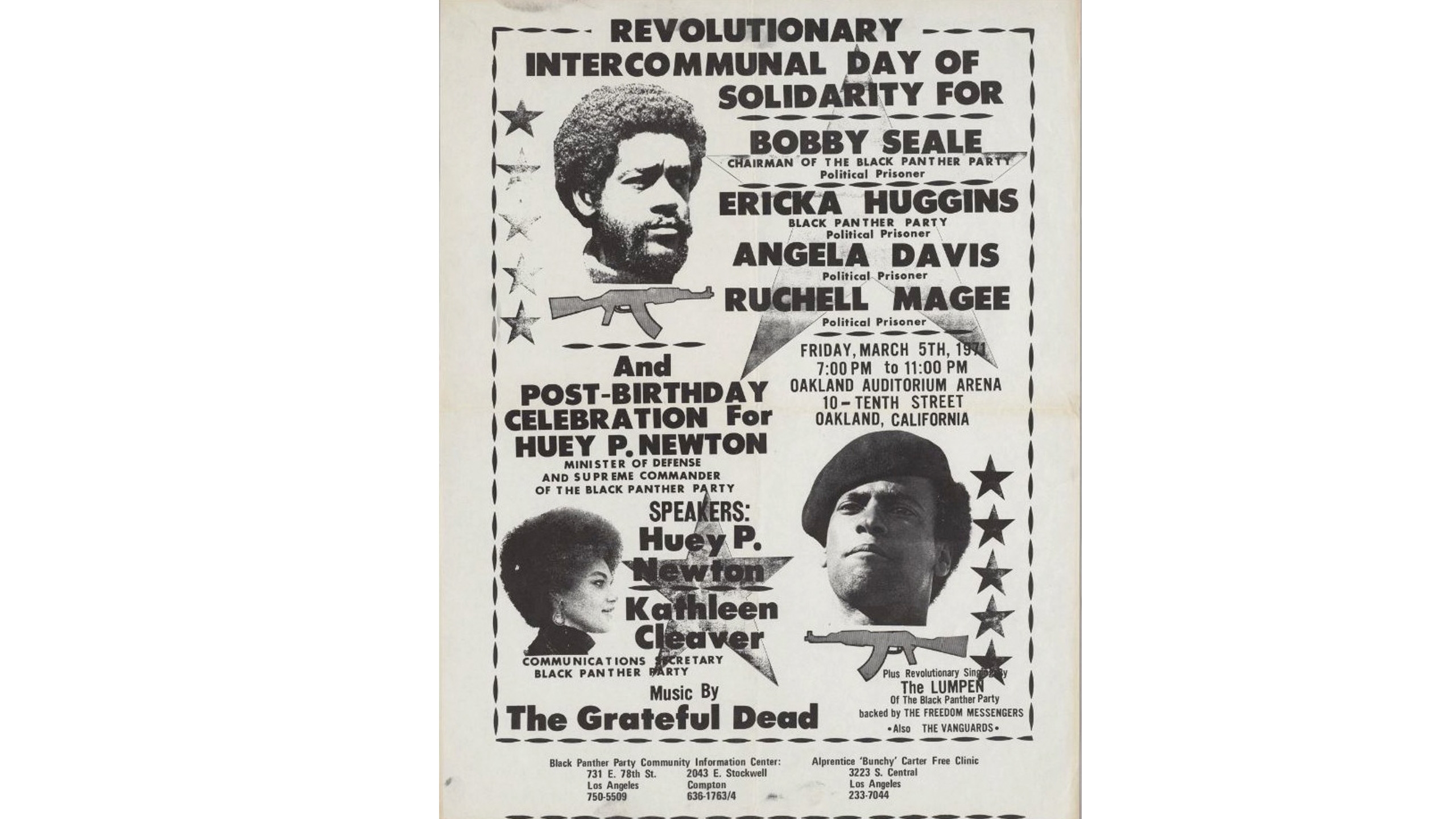

Unlike many other left publications, which tend to narrow after launch to fit the agenda of their core participants, Viewpoint has upheld a striking diversity of content. A broad array of anti-capitalist thinkers have featured on the website, with a notable bias away from living ‘Marxist celebrities’, and towards younger thinkers. Over the past seven years, the result has been an omnivorous materialism that ranges from Lenin to Lacan, and from strategic re-imagining of strikes, to obscure 1971 anti-prison polemics by well known thinkers, to reflections on the Black Panther Party’s struggle with the household. As a publication which relies on web browsers, Viewpoint pays no heed to outmoded concepts such as page counts. Each ‘issue’ really amounts to enormous compilations of hypertext, often openly dreaded even by paid-up admirers, due to their consistent high quality and vast word count. (Viewpoint is engaged in something of an undeclared rivalry with the communiser journal Endnotes in this respect, both collectives exploring the outer reaches of ‘tl;dr’.)

Despite the high volume of its ‘output’, Viewpoint’s small team, and the low overheads associated with online publication, have allowed for certain editorial idiosyncrasies to play out over the years. These include several in-depth explorations of the career of French theorist Louis Althusser, and a string of lengthy pieces on country music’s origins in the cultural strife of the US South. In this way, the magazine gently advances various agendas through its selection and commissioning of materials, while building up a unusually broad and engaged readership of Marxist politicos. This near-unique positioning reduces the need for direct offensives on the part of its editors, who now increasingly often release timely polemical missives under their corporate vox. Altogether, the result is that traditional media has been largely irrelevant to the distribution and continuous development of this distinctive communist perspective. This self-fashioned platform probably has a lot to do with the minimal style adopted in Mistaken Identity. Taken in light of the dedicated following (and collective ‘line’) developed by Viewpoint, individual members of the collective can afford to be partial, even in a manuscript for a major left publishing house. But an upshot of this evasive, collaborative approach is that only an implied account of the differentiation of left-wing opposition to identity politics, and the cruder ‘anti-identitarian’ stance, actually appears in the book itself.

Despite its brevity, this is by no means an introductory text. Rather than offering a full account of what is missing from Mistaken Identity, this review will instead focus on what the book does provide. Although not comprehensive, the arguments advanced by Haider’s debut are, by turns, provocative and subtle. On occasion, the book is too subtle. While Haider is keen to distinguish his arguments from ‘workerist’ positions on identity, a degree of unpicking and highlighting is still necessary to demonstrate how these arguments differ.

The book opens with an account of the author’s childhood, as a Pakistani American, raised in Pennsylvania, who came of age during the War on Terror. Lacking any clear sense of cultural attachment, and unmoored from the experience of his more ‘all-American’ peers (particularly acute in the wake of the WTC terror attacks, and the subsequent intensification of state racism), Haider’s description of his youth is filled with the unease and disenchantment we might expect of a cosmopolitan communist:

Between the white kids in Pennsylvania who asked me where I was from (not Pennsylvania, apparently) and the Pakistani relatives who pointed out my American accent, it seemed that if I did have an identity, no one was really prepared to recognize it.

While coming of age in Middle America, as Haider has put it during a public discussion of his book, he decided to become an internationalist revolutionary, rather than American. Reading the writings of Huey P. Newton and Malcolm X in his local library first drew him into the politics of Marxism and anti-racism. He was further inspired by British Pakistani social critics, especially Hanif Kureishi’s explorations of fundamentalism and secularism (also a point of reference in a recent reflection on what it means to be ‘culturally muslim’ by Haider’s twin brother). Although neither sets of writers shared Haider’s exact social position and teenage experiences of life, the commonality in experiences and conclusions drawn by black Americans and British Pakistanis were still clearly key material in the development of his thinking, and ultimate refusal of any sense of national attachment.

Later in the book, echoing his autobiographical account of adolescent engagement with British accounts of culture and postcolonial identification, Haider turns to Birmingham’s most famed cultural theorist Stuart Hall. Haider sees Hall’s analysis of post-war Britain as offering an analogous account of the rise of Trump, and US nativism more generally. In Policing the Crisis and ‘The Great Moving Right Show’, Hall and his research unit, the Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies, presented a counter-intuitive argument concerning the rise of the insurgent New Right. The ascent of the ‘law and order’ agenda, they argued, reflected not primarily on developments within the Conservative Party (which had always featured a sizable ‘hang ’em and flog ‘em’ grassroots contingent), but instead a striking failure by the Labour Party to offer a compelling response to shifts in British racialisation and urbanism. The Labour Party’s role during the British inter-war settlement was largely a ‘containment’ of working class militancy. The justifications for ever harsher and more pervasive ‘law and order’ measures in the face of ideologically conceived black criminality thus doubled up as a means through which the state suppressed worker militancy (which occurred across ethnic lines). In this context, Thatcherism wrong-footed the Labour Party by exploiting its dependence on a conception of the state as a benign representative of national interest, over sectional class antagonism. The result was a potent brew of ‘authoritarian populism’, to which, as Hall correctly identified, the Labour Party had no clear response.

Much work remains to be done here (perhaps in the form of a lengthy Viewpoint essay): the similarities between the 21st century US Democratic and late 20th century UK Labour Parties deserve careful attention, as would a comparison of those countries’ respective migration histories and local traditions of political nativism. Haider himself states that ‘authoritarian populism’ may be an insufficient term when evaluating the particular rise of the US hard right. Nevertheless, this reconstruction of a debate within British political analysis illuminates the contemporary politics conditions of the United States (and is also the only point at which the text justifies its unimaginative unit-shifting subtitle ‘Race and Class in the Age of Trump’, presumably selected by the publishing house). However, it seems clear enough that one key commonality holds: the Democratic Party has no more coherent response to the rise of Trump than the 1970-80s Labour Party had to the ascendency of Thatcher. Through focusing on another context altogether, Haider avoids the compelling celebrity gloss and social media trolling of President Trump, to hint at the bipartisan underpinnings of the current triumph of American nationalism.

By contrast, the book’s weakest point is a reflection on the strange, thoroughly American case of Rachel Dolezal. This ill-advised section is weaker still for being situated in an otherwise excellent chapter comparing Amiri Baraka to Philip Roth as accomplished residents of New Jersey—an inspired analysis to which the Dolezal musings bear little relation. Haider makes the unconvincing claim that Dolezal shows up how ‘we are all passing’ — a claim which pays no attention to the frequent invocation of Dolezal as a right-wing and transphobic feminist talking point, intended to discredit trans identities by equating them with ‘trans-racialism’. There is also no engagement with the many black feminist responses to the episode— in glaring contrast to Haider’s careful engagement with the early New Left.

Mistaken Identity is a book opposed to ‘identity politics’— a position which is fully informed by a reading of the earliest proponents of that same term: the black lesbian feminists of the Combahee River Collective. Haider freely admits that the famous Combahee River Collective Statement explicitly calls for a politics of identity: analysis and action informed by the experiences of oppression on the part of the black lesbians who made up the Collective. But Haider is keen to stress that the Collective itself did not refuse collaboration with other groups, and that even in its founding statement they opposed separatism. Haider returns repeatedly to the Collective throughout the book, including in his conclusion, where he enlists them as an historical example of ‘insurgent universalism’. In one of the book’s stronger passages, he takes up accounts from the group’s founders to show that it arose in direct response to widespread chauvinism within black nationalist politics—in other words, how even this explicit call for ‘identity politics’ arose from existing failings in identity-centred political activity. Clearly, as a critical account of ‘identity politics’, Mistaken Identity sets out to be more discerning than most.

Indeed, as Haider admits in a response to his book’s hostile reception, he is a sceptic concerning the soundness or fixity of any given individual’s identity:

We can never have a total understanding of what has determined our selfhood. There is a multiplicity of causes beyond our ability to perceive: at a basic level, purely physical things that affect us without our conscious awareness, and at the most complex level, all the historical factors that have determined us as social beings. We can form a partial, incomplete awareness of this in our imaginations, but at this level, a full understanding of the history of our selves will remain elusive.

To put it another way: rather than relating the importance of race as an identity, Haider’s intention is to reveal any identity’s innate unreliability. To begin with identity as the basis for political organisation is to erect one’s strategy atop shifting sands.

In weighing up the case against identity politics made by Mistaken Identity, it’s hard not to recall an essay by Jeremy Gilbert, which I also cited last year when evaluating another (incomparably weaker) contribution to the identity debate. As part of his eulogy to his late friend Mark Fisher, Gilbert offers an account of early left opposition to identity politics. These positions, which Haider also seeks to recover, have increasingly become forgotten as the debates continued, and opposition to the strawmen of ‘postmodernism’ and ‘PC culture’ became key right-wing shibboleths. Gilbert writes:

Both Judith Butler’s early forays into queer theory and Kimberlé Crenshaw’s articulation of the theory of intersectionality were specifically intended, at least in part, as critiques of this form of essentialist, individualist identity politics. Heroes of Cultural Studies such as Stuart Hall and Paul Gilroy have always argued against it as disabling and politically regressive in its implications. If you didn’t understand that that’s what they were saying, then you weren’t paying attention.

Haider shares this reading. Mistaken Identity is a deployment of continental philosophy, not an attempt to discard it. To those familiar with Haider’s editorial work, this is not especially surprising. Whereas many leftists sceptical of critical approaches to identities are prone to joining the right in decrying ‘postmodernism’, Viewpoint have consistently attempted to integrate thinkers often taken to be outside the Marxist canon, most notably Michel Foucault. Demonstrating the Magazine’s distance to cruder left critics of social theory, this January Shuja Haider wrote a review — knowingly entitled ‘Postmodernism Did Not Take Place’ — of Jordan Peterson’s botched reading of the history of thought. At once this essay draws out the absurdity of Peterson’s conflation of Derrida’s deconstructive work and genuine neo-Marxism, while refusing to dismiss (or crudely oppose) either school. A similar approach of re-reading and syncretising can be found in Mistaken Identity. Although the book is explicitly about race, rather than gender, the work of Judith Butler is deployed analogously to grasp the ways in which racial identification is a continual point of fracture, and contention.

Haider is most indebted to Butler’s argument that the sole sound political reason to focus on identities is to better refuse the role they play in state discipline. In this view, the lack of fixity found in identities exactly validates them as a political concern: continual divisions demanded by the prevailing order can be best resisted by bringing into focus the schisms within the social fabric— schisms that the ruling class would otherwise face no resistance in exploiting. Butler presents gender as an inevitable source of ‘trouble’, which must be accepted as an ongoing battleground which progressive movements will have to confront, just as reactionaries do. Following from this Haider argues:

We can’t possibly achieve this if we take these forms of individuality for granted—if we accept them as the starting point of our analysis and our politics. Clearly “identity” is a real phenomenon: it corresponds to the way the state parcels us out into individuals, and the way we form our selfhood in response to a wide range of social relations. But it is nevertheless an abstraction, one that doesn’t tell us about the specific social relations that have constituted it. A materialist mode of investigation has to go from the abstract to the concrete—it has to bring this abstraction back to earth by moving through all the historical specificities and material relations that have put it in our heads.

Haider explicitly sides with Butler against what she calls ‘foundationalism’: the assumption that one can ever truly call upon groups such as ‘women’ or ‘Muslims’ as a given, which can be treated either as a target for state policies, or as a rallying point for revolutionary politics. Identities should be focused on precisely so they can be called into question, and new forms of solidarity across fissures and ruptures should be sought out actively by revolutionaries.

Typically, Marxist theorists have been most wary of Butler exactly around this deconstructive aspect of her thought: if thinkers are to take such a tack toward womanhood, class-minded sceptics murmur, then what hope for the proletariat? Notwithstanding these fears, Mistaken Identity embraces these arguments as a means of rejecting what Haider terms ‘identity politics’ without the co-opting of reactionary ideas or sentiment.

Butler’s appeal for Haider is that her account offers a process of self-identification as a psychic response to wounding. As she has it:

Called by an injurious name, I come into social being, and because I have a certain inevitable attachment to my existence, because a certain narcissism takes hold of any term that confers existence, I am led to embrace the terms that injure me because they constitute me socially. The self-colonising trajectory of certain forms of identity politics are symptomatic of this paradoxical embrace of the injurious term.

This passage is strikingly similar to a famous passage from Frantz Fanon’s Black Skin, White Masks. Here, Fanon recounts encountering a racist child on a train in France, and the newfound identification this brought about in him, as a black colonial subject:

Sealed into that crushing objecthood, I turned beseechingly to others. Their attention was a liberation, running over my body suddenly abraded into nonbeing, endowing me once more with an agility that I had thought lost, and by taking me out of the world, restoring me to it. But just as I reached the other side, I stumbled, and the movements, the attitudes, the glances of the other fixed me there, in the sense in which a chemical solution is fixed by a dye. I was indignant; I demanded an explanation.

Nothing happened. I burst apart. Now the fragments have been put together again by another self.

These accounts are each powerful in describing identity as a matter of responses to domination, and constitutive injury. They convey the way that identities are imposed upon individuals through social relations, and in traumatic, lopsided encounters.

Along with Butler, Haider draws upon Wendy Brown’s incisive criticism of the contemporary left’s attachment to melancholy. Brown allows for a linking of the risks of liberal politics of securing ‘rights’ with the account of identities as injuries: allowing any identity to be defined in terms immediately risks them being defined only by reduction to victim status.

Overall, this account of identity is a strikingly psychoanalytic one: framing the individual’s attachment to their more abstract social position in terms of (psychic) injury, narcissism, and melancholia. Another feminist psychoanalytic thinker Jacqueline Rose (not cited by Haider), captures the compelling ambivalence of this school of thought when considering contemporary identity politics. Rather than explaining gender as a mechanism deployed by society, psychoanalytic feminists stress how womanhood is (invariably) defined by failure, and strain:

The unconscious constantly reveals the ‘failure’ of identity. Because there is no continuity of psychic life, so there is no stability…of sexual identity, no position for women (or for men) which is ever simply achieved. Nor does psychoanalysis see such ‘failure’ as a special-case inability or an individual deviancy from the norm. ‘Failure’ is not a moment to be regretted in a process of adaptation, or development into normality, which ideally takes its course. Instead ‘failure’ is something endlessly repeated and relived moment by moment throughout our individual histories…Viewed in this way, psychoanalysis is no longer best understood as an account of how women are fitted into place. Instead psychoanalysis becomes one of the few places in our culture where it is recognized as more than a fact of individual pathology that most women do not painlessly slip into their roles as women, if indeed they do at all.

While providing a powerful means for Haider to advance an innovative position on the nature and limits of identity, the upshot of relying on such an austere palette is that Mistaken Identity can be quite a bleak read. In contrast to the firm assertions of ‘lived experience’ commonplace among contemporary leftists, this is an account that plays up doubt, and hesitation. Yet Haider seems quite unambiguously committed to this framework, to the exclusion of various other relevant schools of Marxist Feminist inquiry. There is, for instance, no insight drawn here from the recent revival of feminist thought centred around Social Reproduction Theory. This is striking given that framework has been advanced by a key piece in Haider’s own Viewpoint Magazine, and a full special issue (sizable even by Viewpoint’s standards, and featuring an introduction co-written by Haider). How racialisation relates to social reproduction remains an open question for future thinkers to grapple with. Additionally, while clearly informed by early queer theory, Mistaken Identity features very little of the spirit of contemporary trans feminism (in either its western, or Brazilian forms). For trans people, identity claims are often hard-won, following years of denial and repression, and possible to realise only through collective life-making activity that plays out on a community level. As recounted by Sophie Lewis, another exuberant tradition within socialist feminism has focused on the figure of the cyborg to present a view of identity formation with greater emphasis on self-making activity and resistance, than injury and identification-as-domination. In keeping with psychoanalytic feminism’s tonal greyscale and emphasis on ‘lack’, Mistaken Identity does not feature cyborgs.

Had Haider opted to focus on gender, rather than race, perhaps a rather more varied picture of identities would have been necessary. But even among scholars focused on racism in the United States, Haider has been remarkably selective. Despite their shared love for the poetry of Amiri Baraka, and his longstanding support of Palestinian solidarity campaigns, Haider makes no mention of Fred Moten’s ‘black optimism’, or Hortense Spiller’s similar view of blackness as a culture. Not even Fanon scholar Achille Mbembe’s well-known, sweeping, and clearly pertinent offensive against what he calls the ‘politics of viscerality’ gets a mention. The result is a sense that Haider has struck out on his own.

While such a short book cannot be expected to engage with every debate going, the nature of minimalism as a style is that each choice made has wide-ranging repercussions. The account found here fills out theoretically something closer to Haider’s own recounted experience: an account of absence, of existing outside. But the resulting psychoanalytic dependence, with its emphasis on identity-as-undoing, leaves the materialist conception of racialisation found in Mistaken Identity poorly equipped to articulate a fully fledged alternative view to its primary rival — the Afro-Pessimists.

Easily the book’s strongest chapter, ‘Contradictions Among The People’, recounts Haider’s experiences as part of the campaign against fee hikes at University of California, Santa Cruz. Following on from the successes and frustrations of Occupy, the campaign took place at a point of relatively intense class struggle in northern California. The experience of organising against his University administration was clearly a bruising one for Haider. As well as being left in doubt about slogans that claimed the costs of attendance rising would ‘Hit students of colour hardest of all’, he was discomfited by the righteous piety that seemed to animate some of his fellow protesters. It was clear that campaigners were beginning to ice out any conception of anti-racism as enmeshed with class war and anti-imperialism — an analysis which Haider informs us was simply taken for granted during his time in the (much smaller) anti-war movement. Left-wing politics was becoming hard to recognise as such. A ‘People of Colour (PoC) caucus’ quickly emerged as an organisational form at once distanced from, and continually in tension with, the main body of protesters. Rather than finding this fraction a welcome reprieve from white workerists, Haider instead quickly found himself completely alienated from a small group of self-appointed representatives, with whom his politics were strikingly at odds. The campaign quickly became preoccupied with inward-facing conflicts, growing oblivious to their inability to overcome the entrenched institutional forces they were supposedly in shared struggle against. In one of the book’s most wry passages, Haider recalls how the dispute concerning the use of the term ‘occupation’ (seen as contaminated by colonialism) saw activists scrambling to find a more palatable framing of their resistance to the powerful university administration.

Haider was not alone in objecting to the drift of campus politics. A November 2014 statement from members of collective Autonomous Students pushed back against occupation being dubbed a ‘white tactic’, among other accusations presented as smears:

Time and time again, our autonomous organising space has been inaccurately referred to as “a white space” for two reasons. First, our politics and our praxis of autonomous organising for worker and student solidarity has resulted in strong affinities with non-POC students and workers whose anti-authoritarian goals and tactics resonate with ours. Second, we absolutely reject the widespread notion throughout our university that we, as POC, will EVER achieve liberation through the administration and institutionalisation of “POC” spaces, which are currently ideologically chained to university authoritarianism…The opportunity to build a movement against capitalist white-supremacy is being attacked by a toxic authoritarian culture, which has created a hostile and unsafe environment for POC autonomous organisers. Accusations of “white supremacy” have been insidiously deployed against POC autonomous organisers and used to silence them.

Haider’s own account of the UC Santa Cruz debacle is endearing for being wholly self-deprecating. Rather than presenting himself in a flattering light, Haider recounts plainly how difficult he found persuading those around him. His appeals to thinkers like Fanon, who he saw as pointing the way towards shared struggle mindful of class, quite clearly failed to land. Through treating himself unsparingly, Haider captures perfectly how difficult it can be to advocate for anti-capitalist solidarity, when caught off guard by the ‘stay in your lane’ left. It’s clear by the end of this account that Haider had failed to hit upon a formula for winning around those sympathetic with the PoC Caucus, and it’s hard not to see Mistaken Identity as a relitigation of this political-developmental injury.

The fierce dispute between People of Colour students and workers revealed by this episode has remained unresolved in the intervening years. The end of this chapter is the first, and seemingly only, point during the book when Haider’s main target—Afro-Pessimism—is addressed openly. This appearance is brief, and unflattering. Haider recounts leading Afro-Pessimist Frank Wilderson’s hamfisted interventions into the prevailing debate around coalitional politics, during which Wilderson argued that it was no surprise so-called ‘non-black People of Colour’ and black Americans would operate with differing (and conflicting) interests. Haider deftly highlights the existing ties between black anti-racist activists and Palestine Solidarity Campaigns in Santa Cruz, over which Wilderson’s sweeping statement on the ‘Arab’ mentality as not only prone to, but structurally founded in anti-blackness rode roughshod.

It’s easy to see how an anti-racist socialist who came of age during the War on Terror could object to Wilderson’s unvarnished assessment of ‘the Arab’ mentality unpalatable, and find his pretext of directly quoting Fanon a flimsy excuse for an apparent display of scholastic racism (much as Wilderson’s similar comments on structural position of ‘the Jew’ caused a small furore during a visit to Vienna). Although Wilderson has expressed his support for the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions movement, a more timely understanding of how state racism has been shaped by the new century’s on-going geopolitical turmoil is surely possible. (And urgently necessary in light of the widespread popularity of President Trump’s proposed ‘Muslim ban’, and this year’s anti-Hispanic scaremongering justifying expanding mass detentions with paranoid references to MS-13, and the migrant caravan.)

But this section is exactly where Mistaken Identity’s brevity is most costly: the tacit approach taken ensures that only those already familiar with Afro-Pessimism will even recognise the book’s primary function as an extended critique of that school. To those familiar with these debates, the subtext is clear. For instance, Wilderson has argued at length against analogous links between gender and race, arguing for the former as a position and the second as a structure,and has targeted Judith Butler specifically in order to demonstrate this. Haider’s deployment of precisely this analogising approach (race understood through gender theory) is at least in tacit defiance of an anti-coalition building perspective. Similarly, Haider describes black thought (from the Haitian Revolution to Huey Newton and the Black Panthers) as reliably at the ‘apex’ of historical struggle, and as such engages primarily with this material — an approach that has been cast by certain activists as Haider (as a non-black person of colour) writing out of turn. Each step Haider takes knowingly clashes with the claims and approach of Afro-Pessimism.

That opposing Afro-Pessimism was the unstated focus of Mistaken Identity has been shown more clearly in a lengthy essay Haider published in Viewpoint, responding to the more astute criticisms of his book from other socialists. Although even here he does not state his intentions plainly, the material marshalled is clearly intended to clarify the book’s purpose as a pushback against Wilderson et al. Typical to his tremendously well-read form, Haider shifts from a reading of Lose Your Mother (by black feminist historian Saidiya Hartman) to CLR James’ account of the failure of Kwame Nkrumah’s leadership of post-colonial Ghana to overcome problems predicted decades before by Lenin. The latter section includes a mention of the original meaning of the term ‘Afropessimism’: decades prior to its current usage, it referred to those who considered black Africans incapable of self-rule due to cultural resistance to modernity. (Besides a citation in a footnote, this is the only explicit use of the term ‘Afropessimism’ in the piece.) Through this introduction of an eclectic array of sources related to Ghana, Haider presents the case that pessimism should not be admitted as an acceptable central feature of radical analysis. Instead, pessimism and despair should be treated as only one moment during the unfolding of revolutionary processes (and by no means a point to be fetishised). Haider’s central reading of Lose Your Mother is especially telling: Hartman is a key historian cited by Afro-Pessimists, along with Hortense Spillers (although neither scholar considers themselves part of the intellectual movement). Haider hones in on, and sides with, a passage where Hartman explicitly refuses the prospect of despair, while confronted with one of the many challenges of doing representative justice to the archival material she works through as a black historian. Here Haider aims astutely for Afro-Pessimism’s underbelly: while Hartman’s archival work and theoretical interventions were heavily relied on by the school, she was never a committed member, and indeed seems increasingly uninterested in discussing the debate. Clearly implied is that another reading of Hartman is possible, among an array of other black radical thinkers.

In contrast to Haider’s wide-ranging and forceful—though still subtle, rather than frontal—follow-up essay, Mistaken Identity itself advances an exclusively strategic account against Afro-Pessimist thought. Frank Wilderson appears alone, and only as a disruptive voice during the already chaotic non-Occupation of UC Santa Cruz, never as a fully fledged thinker, to be properly refuted. Haider does not delve deeper into the relevant points of dispute, especially an apparent divergence in revolutionary views on ‘anti-blackness’. This risks producing yet another anti-Afro-Pessimist account which skims over the surface of this provocative school for objectionable material, rather than grappling with its strongest claims in earnest.

This is especially troubling, as there is clearly more shared ground than Mistaken Identity admits to. On a descriptive level, the Afro-Pessimist account of systemic racism is more challenging to class warriors than Haider seems willing to admit. Much like Haider’s account of identification-as-injury, the Afro-Pessimist understanding of the distinct position of anti-blackness within racism relies heavily on psychoanalysis: the unconscious is taken to be structured to promote certain prejudices on an inescapable level. These subterranean pathways in the pooled psyche foreclose certain purportedly revolutionary motions, blockages that cannot be pushed through by force of will. These obstructions, Afro-Pessimists argue, ensure that a universal emancipation through a coalition of interests can never be achieved, with the only remaining option being to ‘destroy the world’.

This is noticeably not an account which affords racial identities an ahistorical character: although blackness is described by most Afro-Pessimists as ontological, this claim is founded in a reading of the structuring of collective unconscious. Rather than an innate feature of society, anti-blackness is based on quite a specific source: the centuries of variations of ‘social death’ bound up with institutions of slavery. This conjunction of slavery and black history, Wilderson argues, extends back to the 8th century Arab slave trade. This is a view of anti-black racism as an inevitable outgrowth of a shared psychic condition shaped by existing global history, not of racialisation as being in any way founded in actual biological partition. Afro-Pessimism also does not reject anti-capitalism, even as it declares it insufficient for the particular struggle of black emancipation, drawing heavily on frameworks from canonical neo-Marxist humanist theorists such as Antonio Gramsci and Frantz Fanon.

While Afro-Pessimism could be considered a ‘neutralisation’ of the potential for anti-racism to be combined with class war (Haider’s brief, unsatisfying definition of ‘identity politics’), it’s striking how much these two accounts have in common. Characteristic not only to the work of Frank Wilderson, but also Jared Sexton and Calvin Warren, is a continual appeal to anti-blackness as founded in unconscious structure. This structural anti-blackness is taken to be pre-eminent, and to hold true across societies. From this follows a rejection of any ‘optimism’ concerning the established race relations industry, or enthusiasm for contingent breakthroughs such as the election of Barack Obama, or a rise in so-called ‘mixed race’ relationships, and families. None of these breakthroughs is the foundation for a post-racial society, for as long as blackness remains an ontologically subordinated (or negated) state. Afro-Pessimism centres a reassertion of black particularity, against what one essay by Jared Sexton refers to as ‘People of Colour Blindness’ — an analytic approach to US racism which conflates the plights of ethnic minorities, losing sight of the distinctive state of ‘social death’ which characterises the black condition (like Haider, Afro-Pessimists refuse the idea of blackness as an identity). The primary purpose of Afro-Pessimist thought is reasserting racial division as an unbridged faultline in US society, against the more upbeat assessments attempted by analysts more invested in the actually existing civil society. But what is also taken to follow from this is an explicit rejection of revolutionary visions that claim to include prospects for black liberation.

In other words, the dispute that surfaces in Mistaken Identity can be read as between two heterodox schools of psychoanalysis, or even as two vying readings of Frantz Fanon: the emphasis on fracturing, injury, and doubt found in feminist psychoanalysis is brought into opposition with a sturdier ontological view of anti-blackness as both the directing force and insidious cornerstone of modernity.

But the difference between Haider and the Afro-Pessimists is also clearly one of style. Afro-Pessimism’s high structuralism allows for stark and provocative statements—that there are no black queers, for instance, or that even the genocide of Native Americans is non-analogous to the ‘gratuitous violence’ that defines anti-black oppression. These claims are not mere flourishes, but central to the project’s structuralism. Key to Afro-Pessimist argumentation is a striking reconceptualisation of American history: despite the undeniable formal changes, the condition of ‘social death’ not having abated for US black people means that they remain ontologically enslaved today. Emancipation was a mere formality. Afro-Pessimists counterpose this view to accounts that are deemed more humanist (which are implied to be fanciful, overly hopeful, and contaminated with Enlightenment racism). The jarring, strident quality of these claims have everything to do with the school’s success as an influential force within academia and certain more socially conscious reaches of the art world, as well as in contemporary anti-racist activist scenes (where Haider first encountered them). The clear lines drawn by this account contrast to the academic tendency to over-balance their prose, or engage in dialectical waffle. Provocations have at once distinguished the Afro-Pessimists from the many other available approaches to understanding racism, and made them near-impossible to ignore. These sometimes inscrutable interventions clearly owe more to the gnomic lecturing style of Jacques Lacan than to the often coalition-minded, and consistently humanist, anti-colonial writings of Frantz Fanon. (While a central figure in the Afro-Pessimist canon, Fanon in fact wrote little on the United States, and considered an emphasis on racial distinction one of the ‘pitfalls of national consciousness’).

Whereas Haider’s style is discreet and heavy on hints and allusions, his Afro-Pessimist rivals have flourished by providing sharp distinctions, emphasising structures above all else, and making bombastic claims that seem to demand responses from rival revolutionary traditions. In refusing to centre the school he clearly has in mind, Haider is largely an unobliging mark. But this refusal of explicit engagement limits the scope for Mistaken Identity’s effectiveness as a proper riposte. The book’s case for class-conscious anti-racism in the US context would probably have been better advanced by Haider providing his own account of ‘anti-blackness’, and outlining the distinction between his stance and that of the Afro-Pessimists’ clearly, and fairly.

Haider could simply have adjusted and repeated arguments he had made previously in a combative piece entitled ‘White Purity’, where he made plain his disenchantment with the aimless ‘privilege checking’ which had become prevalent among white leftists and liberals. This piece sees Haider, once again, retrieve and re-read a by-gone New Left debate, to intervene into the present state of political discourse. While making the case for the indispensability of class war for anti-racist activism, Haider approvingly quotes Noël Ignatiev’s debates with armed struggle group the Weathermen (whose members were almost exclusively white anti-racists). During an unsparing debate, Ignatiev argues that ‘white-skin privileges serve only the bourgeoisie’, and memorably compares the white worker’s condition to a fish being fed poisoned bait. This is coalitional politics at its clearest: survival for the entire proletariat demands a unified uprising against a shared class enemy. By contrast, Haider dryly summarised contemporary white anti-racists as offering only: ‘endless variations on the Weatherman position, though without the appeals to armed struggle, bank robberies, and Lenin’s theory of imperialism.’

This earlier essay makes clear the impasse: while Afro-Pessimists are sceptical about the possibility for revolutionary emancipation from anti-blackness (and as such see the overturning of capitalism as insufficient for ending systemic domination), Haider considers anti-colonial and anti-racist struggles as standing or falling on the basis of their disciplined attentiveness to class analysis. Neither race alone, nor any other one feature of an identity, can be relied on — Haider follows Stuart Hall’s maxim that ‘race is the modality in which class is lived’. Mistaken Identity delicately fills out this position, marshalling a prescient collection of black thinkers to support Haider’s continued commitment to coalitional politics. While for Afro-Pessimists, the white proletariat and bourgeoisie have a shared interest in sustaining themselves through anti-blackness, for Haider the white and black proletariat have a shared interest in class war, and ultimately require one other for revolution.

Given how much of the work required was already done elsewhere, it’s puzzling that this book (supposedly exclusively about race) falls short of a proper refutation of its target. While Haider’s refusal to make a plain case for his position may simply have been based in a reluctance to give Afro-Pessimism further exposure, a less charitable reading is that Mistaken Identity suffers from a failure of nerve.

In particular, a certain double standard appears: it’s hard to see how Mistaken Identity’s exclusively strategic dismissal of Frank Wilderson could not apply to Judith Butler, too. Famously, even the finest theorists can abandon their political intransigence in matters related to the campus. Haider relies on Butler’s work on identifications despite her ill-advised liberal complaints concerning the successful protests which prevented Milo Yiannopoulos from speaking at UC Berkeley. Haider presumably sides with protestors who moved to ensure Yiannopoulos from singling out trans students for harassment, or identifying targets for ICE to deport. In itself, this particular disagreement is of no decisive import, but with the case against Wilderson being left to rest in exactly these terms, Mistaken Identity comes short in consistency. Clearly, Haider is of the view that at least some thinkers can have their analytic work unmoored from their practical (or impractical) suggestions.

In his avoidant treatment of both the ‘class reductionist’ left, and the Afro-Pessimist account of blackness as ontological condition, Haider demonstrates the same approach. Firstly, fleeting engagement, followed by an attempt at implicit rebuttal through careful canon building, and historical recounting of key moments that support his favoured political positions. The result is a deft retracing of battle lines, rather than any real offensive against the primary actors sceptical of a coalitional anti-racist militant movement. This is an account for readers satiated by attentive exegesis, rather than fireworks.

Nevertheless, Mistaken Identity is a worthy contribution to a highly fraught debate. The book rewards a patient reading, and provides enough citations last a lifetime chasing up. In the last instance, though, the politics Haider has done so much to cultivate (in various forums) warrant a further, more explicit airing.

While Haider’s reluctance to offer a clear definition of ‘identity politics’ may have fine philosophical pedigree, the upshot is a predictable rhetorical failing. Despite demonstrating handily that the thinkers and actors he marshals share his basic strategic commitments to ‘insurgent universalism’, it’s hard to imagine any full-throated critique of ‘identity politics’ today attracting a sizable audience already familiar with both the black radical tradition, and Judith Butler. Today, the term is mostly associated with right-wing political personalities, and the worst parts of the left (with Neoconservatives drawing from the second pool to replenish the first). It’s unclear why Haider expects his usage of so contaminated a term to illuminate (rather than confuse). And it’s equally unclear why he expects his subtle account to win out over more crude ones. This failing is made all the more acute by Haider’s unwillingness to engage openly with the class reductionist left, who today make heavy and derisory use of the term ‘identity politics’, as they seek to define their often vague political commitments against an even more vaguely-defined horde of subversive ‘identitarians’. Few of this canonically challenged ilk seem likely to reach the end of a book which begins by speaking favourably of the Black Panthers, and Malcolm X. Nor is it easy to imagine any serious number of Afro-Pessimist scholars or activists being won around by the book’s stealthy approach. As a counter-recruitment tool within contemporary anti-racism, the job is left half done: without any explicit effort to overcome the clear overlap between Haider and Wilderson’s intellectual commitments, the true dispute in play is left to course as an underground current.

The fleeting, tacit nature of Mistaken Identity’s argumentation has already led to much misconstrual and dismissal. Haider’s two lengthy responses to this were welcome, but somewhat decisively demonstrate that the text struggles to stand alone. That so many reviewers have struggled to grasp this short book does not bode well for the reach Haider might have hoped for. The ‘inside baseball’ crowd of Marxist theory nerds may well be familiar with the accompanying line developed elsewhere, and already have a perspective of their own on anti-blackness, and how it relates to the prospects for revolutionary activity in the 21st century. But for a general audience, the true intention and context of Mistaken Identity would not be so clear. In 1979, during one of his fiercer debates with Marxist historian EP Thompson, Stuart Hall warned against the limitations of polemics. Haider seems to overcorrect for this, presenting an understated case which could have benefitted from a more committed offensive. While Mistaken Identity is a considerably more delicate and illuminating work than many previous interventions into the field, its approach is too low key by half to create the lasting impact that Haider’s underlying thinking deserves.

With thanks to Robert Cuffy for an insightful conversation on the book’s treatment of workerism, and Fainan Lakha for her pointers on structuralism, Althusser, and pessimism (which this essay has merely hinted at).