What happens when the most firmly held of common senses meet the hard reality of political transformation?

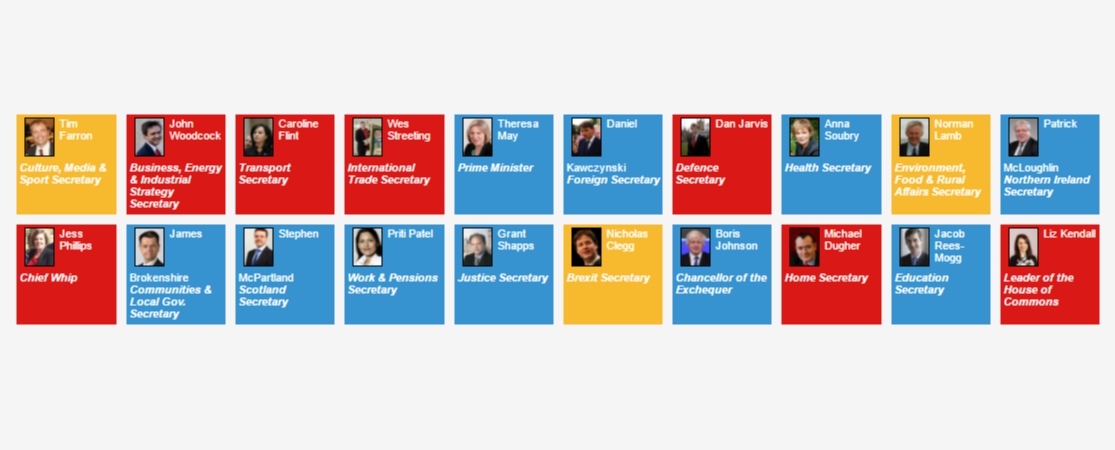

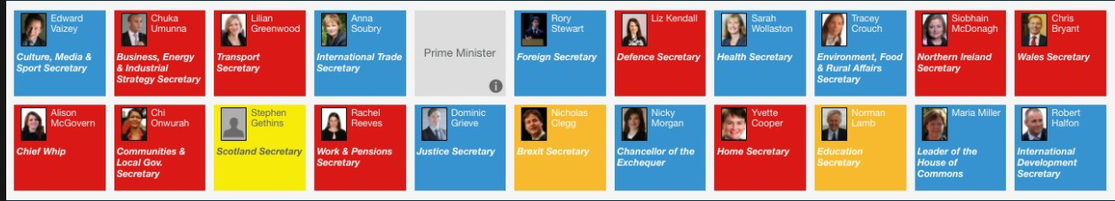

What happens when the most firmly held of common senses meet the hard reality of political transformation? The 2017 election result has proven to be a live experiment in such a collision between a hegemonic ideology and its imminent destruction. One such common sense can be identified at work in the prevalence of fantasy cabinets being shared on social networks, on ready display in the early weeks of the 2017 campaign. Largely the preserve of liberal journalists, these imagined cabinets consisted of a bizarre melange of ‘centrist’ and ‘sensible’ MPs from different parties, seeking to create some kind of dream line-up of pure neoliberal efficacy.

A fantasy frontbench

On the one hand, this was spurred on by the development of a ‘fantasy frontbench’ app, but the uses to which it was put are telling of the mindset of a generation of opinion makers, and the ideological environment in which they themselves have been formed. It is in our fantasies, even those shared for amusement, that we can locate something of the truth as it is moulded by a system of power. In some ways harking back to the halcyon ‘rose garden’ of the first moments of the 2010-15 Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition government, these fantasy cabinets sought to get past the tiresome business of actual political conflict, with its material interests, policy programmes, and passions. Instead we were to imagine what might put all these things to rest, a government of ‘talents’, for the national interest.

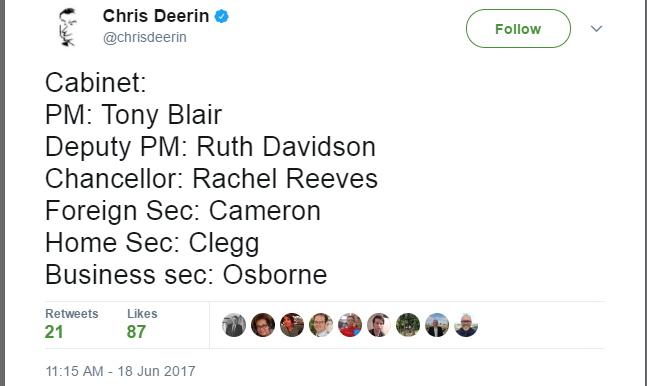

Even after the election result itself, with the best gains in proportion of the vote since 1945 for Corbyn’s Labour Party, there were calls for his internal opponents to be incorporated into the new shadow cabinet. There might be some sense in the inclusion of MPs such as former leader Ed Miliband, who had commented during the campaign that he wished he had run on a manifesto such as Corbyn’s, and who had been supportive during the campaigning itself. Internal opponents such as Chuka Umunna and Yvette Cooper are another matter entirely, having been preparing their own leadership bids in the weeks before election day. Moreover, it was difficult in the extreme to identify what, precisely, these alleged luminaries were going to bring to the table – what they might add to Corbyn’s new socialism.

Much of the appeal of this sort of fantasy politics rests on an entirely denatured conception of what politics is, where those who have had the best contacts in the media, and hence who have been lauded as being uniquely talented, are put forward as being the saviours of a corrupted system. Fantasy cabinets can here be seen to be of a piece with the obsessive return to such cultural products as The West Wing, which dissolved political differences in an acid of glib technocratic competence. A powerful fantasy is apparent amongst the liberal media class of doing away with politics all together, and replacing it with management and marketing – a fantasy that has been all the more powerful because of its apparent ‘reasonableness’.

We should consider such outpourings of centrist longing to be a prime example of the post-democratic, even post-political condition which has beset British politics over the last few decades. Such longings are at their strongest at the very moment when the system which has nurtured them is fading away, an almost nostalgia for that which still exists but perhaps for not much longer. That such fantasies are reaching their apogee should not surprise us given our moment’s apparent location at the end of a long period of relative dynamic stability, the era of neoliberal hegemony. This hegemonic bloc had many distinguishing characteristics, amongst them an overarching tendency towards post-democratisation, whether deliberately willed or merely an acceptable side-effect.

Post-democracy, as laid out by Colin Crouch, is a condition wherein electoral turnouts become lower, major political parties hollowed out and with significant declines in memberships, policy platforms coalesce around a fairly narrow ambit of options, and faith in elections as a method to transform our world declines precipitously.1 The years of Blair, Brown, and Cameron, can now be identified as being the high tide of post-democratisation within the United Kingdom. In this era, a key driver of the reduction in the ability of democracy to function was the limited range of choice between the parties, their overriding agreement on the basic rules and function of politics: a managerialist paradigm of reformist tweaks to an economy and society set into motion under Thatcher. This neoliberal consensus meant in turn that professional politics attracted an ever decreasingly diverse selection of people, famously largely restricted to PPE graduates from Oxford University. The willing collaborators in and enablers of this post-democratic turn were mainstream journalists (of both left-liberal and right wing stripes), who both re-enforced the Overton window of acceptable opinions and also the emergent star system of bland technocratic managers which our political class had become.

Chris Deerin playing along

Yet what the 2017 election offered was something quite distinct from the decades of political gruel that had come before. Global dynamics had begun to put serious tension upon the existing neoliberal consensus. The Brexit vote and the election of Donald Trump in the US in 2016 were only the most sensational symptoms of the emergent sense that politics as it had been was shortly to be no more. As such, both the Labour and Conservative Parties attempted (with differential degrees of success) to offer something of a break with neoliberalism as it had been practiced. For the Tories, and their leader, Theresa May’s chief advisor Nick Timothy, this meant some minor shifts towards a more nativist and authoritarian programme. For Labour, this entailed a dramatic shift in the direction of travel towards a social democratic offer, including revoking or reforming some hallmark neoliberal policies such as privatisation of certain public services, higher education fees, and elements of austerity.

What was driving liberal journalists’ recent dive into fantasy politics and the development of absurd cabinets was simply the fact that they no longer liked or understood politics as it was playing out. With a significant choice between Labour and Conservative parties, the political had returned. In its wake, there was a sense that our media class were deeply uneasy, leading to all kinds of phantasmagoric projections of post-political or anti-political centrism. The significant differences between the policy programmes and political outlooks of the two major parties meant that the usual liberal journalistic practices, largely centred on gossip, personality politics, and often dubious psephology, had fallen away. Though the real material conflicts in our society, along class, racial, and gender lines had never disappeared (and indeed have in many senses been heightened) the role of political journalism under the neoliberal consensus operated largely to conceal them. Yet it was increasingly clear over the course of the campaign that these conflicts were returning to the fore. Rather than a contest based on who could be presented as the most ‘professional’ or ‘effective’, an election of marketing and consensus, this was a full-blooded return to a politics driven by conflicts & interests.

As the election result and the week which has followed has demonstrated, the politics of the neoliberal era is crashing to an abrupt conclusion. We can see in the election of Jeremy Corbyn as leader of the Labour Party in September 2015 the beginning of a new and very different fantasy of what is possible within the politics of the UK – one which had of necessity to begin at the level of the fantastic, the improbable, even the impossible. At every stage Corbyn, his supporters, and the politics they supported were seen as retrograde, juvenile, inherently ridiculous, and overwhelmingly impractical. Yet they have proven capable of accelerating the most significant hegemonic break in the UK for decades. What had been a ludicrous fantasy a mere handful of weeks ago is now fast becoming real. The post-political and post-democratic dreams of our media elites, a symptom of the broader malaise and dysfunction of our parliamentary politics over the last forty years, should shrink and die in the light of these new times. In their wake, it is our duty to dream again, to imagine and force into being a new democratic culture, one resolutely resistant to the reactionary desire to be done with politics.

-

Colin Crouch, Post-Democracy, London, Polity, 2004. ↩