Jeremy Corbyn's media reform speech was a good start, but flawed - it severely underestimated the scale of the media crisis.

Jeremy Corbyn’s Alternative MacTaggart Lecture was a welcome first step towards developing a bold programme of media reform. Traditionally, Labour has ignored this area. Under New Labour, the party sought not to challenge oligarchic media power, but to pander to it in the hope of favourable treatment - an essential element of the broader strategy of accommodation to neoliberal capitalism. Murdoch was the “24th member of the cabinet”, reportedly on the phone to Blair several times in the run-up to the invasion of Iraq.1 And this while Labour ministers and MPs were being illegally spied on by private investigators working for journalists at Murdoch newspapers.2 Under Ed Miliband, the 2011 phone-hacking scandal saw Labour finally challenge the right-wing press by calling for a public inquiry. But having antagonised the press barons, the advantage was not pressed with bold rhetoric or imaginative proposals.3

Under Corbyn, there have been two shadow culture secretaries. Michael Dugher was sacked in January 2016; his replacement Tom Watson has done little in nearly two years in the job. The main issue in that time has been Rupert Murdoch’s attempt to acquire Sky, about which he has failed to write so much as a letter, let alone a full submission, to either Ofcom or the CMA during their inquiries into the bid.4 His only policy announcement has been that Labour will ‘review media ownership rules’ when in government - essentially proposing that someone, ideally someone else, will someday develop a policy. In 2016, Watson chose Dugher to deliver a report on the problem of ‘fake news’ - presumably to thumb his nose at Corbyn for sacking his predecessor. No report ever materialised. Corbyn’s speech is filling a major policy vacuum for Labour.

Turning to the speech itself, Corbyn’s fundamental claim is that “while we produce some fantastic drama, entertainment, documentaries and films, when it comes to news and current affairs, so vital for a democratic society – our media is failing.” (The state of our broader cultural production is not as good as this suggests, but polite words in the speech are understandable.) In this response, I will look at the symptoms of failure Corbyn’s speech identifies, his account of their causes, and his proposed remedies. I argue that his account of the symptoms of failure is too brief and limited, his explanation for our news media’s failure incomplete and his proposals not bold enough. At the end, I outline a proposal for publicly funded and democratically controlled journalism. Despite my criticisms, it is worth reiterating that this is easily the most cogent speech a Labour leader has ever given on the media, and a good start to the vitally important task of developing a radical agenda in this area.

Our failing news media

In his speech, Corbyn pointed to two ways ‘our media is failing’: first, low public trust in our news media, and especially newspapers. “The British press is the least trusted press in Europe, including non-EU countries like North Macedonia and Serbia.” In fact, “for all the worry about new forms of fake news we’ve ignored the fact that most of our citizens think our newspapers churn out fake news day in, day out”. These are necessary words at a time when the press is attempting to position themselves as the purveyors of ‘high quality journalism’ and portraying ‘fake news’ as an exclusively online phenomenon, nothing to do with them.5 Corbyn also observed that “in the last four years one political earthquake after another has been missed by most of our media.” Again, a valid criticism. Yet the failures go far beyond low public trust and not predicting ‘political earthquakes’.

The most obvious and fundamental failure, unmentioned in the speech, is the collapse of journalistic employment and the mass closure of newspaper titles over the last decade. A report for the Cairncross Review into press sustainability claims that more than 300 local newspapers have closed and 6,000 print journalists have been laid off in the last ten years, with 136 local and regional titles closing since 2012.6 Nor is the situation much better online: in mid-2016 the Guardian announced a hundred planned editorial redundancies. BuzzFeed UK announced it was laying off a third of its UK news team at the end of last year. There has been a similar story in the US, where overall newsroom employment dropped by 23% between 2008-17, from 114,000 to 88,000, with jobs in newspaper newsrooms falling by 45% and accounting for virtually all of the decline. The BuzzFeed business reporter who wrote an article in 2016 titled “The Digital Media Bloodbath: Hundreds Of Jobs Lost” found that a year and a half later, he had lost his job too.

This disaster has had two major consequences. First, less original reporting. There is now a lack of detailed coverage of many areas of our civic life: our schools, hospitals, trade unions, police, courts, prisons, local councils, political parties and Parliament itself. The collapse has been severest in local journalism, with the consequence that in many areas there are few easy ways for most people to become informed about what their local authorities, or a whole range of other institutions, are doing. Nor is informed and independent-minded science and foreign coverage anywhere near as abundant as it should be. Ask yourself, for instance, how many British news outlets offer good coverage of German politics? Today, serious business and financial news is mostly provided by services, like Bloomberg, Politico and the Financial Times, dedicated to meeting the needs of business and financial institutions, with all the biases that flow from that. The straightforward consequence is that the public is being poorly informed. A range of scandals are unquestionably being missed.

Another consequence is that those institutions with the resources to present stories pre-packaged have acquired more power to frame stories about themselves, and more influence over the news agenda. State institutions and large corporations have hugely increased spending on media management in the last few decades. Corporate-funded pressure groups and think-tanks have also come into their own in that time.7 Journalists are laid off while the PR industry grows - indeed, PR is often the next job for recently laid-off journalists. Overstretched, with little time to do independent research, journalists find accepting the official or PR version of events easier and quicker. So our most powerful institutions lack independent, critical and professional scrutiny because uncritical stenography is cheaper and easier. The decline has been one of quality as well as quantity.8

Other than coverage of Labour under Corbyn, the speech didn’t point to any specific issues where the media’s coverage has ‘failed’. But there are plenty to choose from. The most obvious example from the last two decades is surely the Iraq War: most of our media not only failed to scrutinise the Blair Government’s claims adequately, but actually became propagandists for the war - with the Murdoch press leading the way.9 YouGov’s long-running ‘trust tracker’ poll suggests the war was one major cause of the low public trust Corbyn identified. Another major, ongoing failure is coverage of austerity, especially under the Coalition.10 Meanwhile, to speak of ‘fake news’ during the Brexit referendum campaign is to mean articles churned out by the Express, the Mail and the Sun.11

Explaining failure

Nevertheless, having identified some symptoms of failure, what explanation for them did Corbyn’s speech advance? Its central claim is that media ownership is excessively concentrated, largely in the hands of billionaires. As a result, it is “too close to the rich and powerful”; “far too few people have a grip on most of the power and it seems like our current system is making that situation worse.” This has degraded journalism: “the owners and editors of most of our country’s newspapers have dragged down standards so far that their hard working journalists are simply not trusted by the public.”

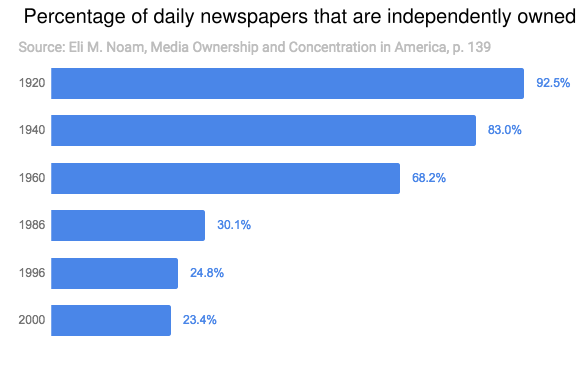

There are three issues here: ownership restricted to the wealthiest individuals and largest corporations, highly concentrated ownership among the wealthy, and the decline of journalistic standards. The first two are, in principle, separable: we could have less concentrated ownership and yet still have a news media owned and controlled exclusively by the wealthy. In 1919, the American socialist journalist Upton Sinclair wrote a book indicting the corruption and anti-socialist bias of American newspapers, The Brass Check.12 He did so because, although American newspaper ownership at the time was far less concentrated than today, newspapers were still largely owned by very wealthy families - what the chart below calls ‘independent’ owners, to contrast them with the large corporate chains which, since the 1980s, have come to dominate ownership.13 In other words, less concentrated media ownership may just disperse ownership among a larger number of wealthy owners or big corporations.14 This is why rules limiting the concentration of media ownership, the probable outcome of Watson’s ‘review of media ownership rules’, are by no means enough.

Second, what is the connection between concentrated ownership, plutocratic ownership, and low journalistic standards? Corbyn’s speech didn’t say. There are supposedly ‘high quality’ news outlets owned and controlled by the wealthy: the New York Times is owned by the Sulzberger family; the Washington Post by Jeff Bezos. The Financial Times was bought by the Japanese media conglomerate Nikkei in 2014 for $1.3bn. These may be media owned by the elite, for the elite, but they can hardly be said to have low journalistic standards.15 They have distinct and pronounced political biases - most obviously, a congenital hostility to the socialist left - but this does not preclude their doing some good journalism, and needless to say for many of their affluent readers that bias, with which they agree, is itself part of what makes them ‘high quality’.

Third, if the underlying cause of the decline journalistic standards is a collapse in the viability of commercial news production, then ending the ownership of the news media by the wealthy won’t necessarily reverse it. Commercial media will face those same conditions whoever their owner. The deterioration of The Guardian (owned by the Scott Trust) over the last decade has occurred simply as a consequence of the commercial environment: no Murdoch figure was necessary. For these reasons, the explanation Corbyn’s speech gave is insufficient to account for the symptoms identified.

An alternative account of the crisis in our news media

Here is an alternative explanation. Newspapers in Western countries, particularly the US and UK, have been in decline for decades. Over the last decade or so, that decline has assumed the proportions of an acute crisis. However, underlying it are flaws inherent in privately produced and consumed news media - flaws which the crisis has exacerbated. Each of these needs to figure in a socialist account of why our news media requires radical reform.

The fundamental starting point is that there are major flaws inherent in the private production and consumption of news. The first is on the production side, and is defined by the cost of owning news outlets. This is a point Corbyn’s speech addresses well, attacking the owners of news media and their degradation of journalism. The issue is worth briefly looking at historically.

In the early 19th century, when printing technology was still fairly rudimentary, the minimum viable circulation of a newspaper was small. The result was, among other things, a flourishing radical working-class press, described in E.P. Thompson’s The Making of the English Working Class:

1816-20 were, above all, years in which popular Radicalism took its style from the hand-press and the weekly periodical. This means of propaganda was in its fullest egalitarian phase. Steam-printing had scarcely made headway (commencing with The Times in 1814), and the plebeian Radical group had as easy access to the hand-press as Church or King…The means of production of the printed page were sufficiently cheap to mean that neither capital nor advertising revenue gave much advantage; while the successful Radical periodical provided a living not only for the editor, but also for regional agents, booksellers, and itinerant hawkers, thereby making of Radicalism, for the first time, a profession which could maintain its own full-time agitators.16

However, this egalitarian access to the press was steadily undermined over the course of the 19th century with industrial development. Ever-larger printing presses became possible. These, together with falling newsprint costs and the rise of advertising meant the returns to large-scale newspaper publishing increased over the century. Rising fixed costs but declining marginal ones tends to produce increasing market concentration. That is what happened in many newspaper markets, as the minimum viable circulation and the cost of market entry rose. According to James Curran and Jean Seaton:

the total cost of establishing the Northern Star, a national weekly newspaper, on a profitable basis in 1837 was little more than £690. It was able to break even with a circulation of about 6200 copies, which was probably achieved in its first month. In contrast the Sunday Express, launched in 1918, expended over £2 million before it broke even, with a circulation of well over 250,000. Thus, while a public subscription in northern towns was sufficient to launch a national weekly in the 1830s, it required the resources of an international conglomerate controlled by Beaverbrook to do the same thing nearly a century later.17

When newspaper publishing was a rudimentary and small-scale activity, ownership and control could remain in the hands of people either in or fairly close to the working class. As it became a bigger enterprise, ownership was increasingly confined to the wealthiest individuals and largest corporations.18 Their ownership has given them editorial control. Since the 1970s especially, that control has been used to trivialise and degrade British journalism. But they have always used it to enforce a systematic bias against the left. As Ralph Miliband put it in 1969:

Rather obviously, those who own and control the capitalist mass media are most likely to be men whose ideological dispositions run from soundly conservative to utterly reactionary; and in many instances, most notably in the case of newspapers, the impact of their views and prejudices is immediate and direct, in the straightforward sense that newspaper proprietors have often not only owned their newspapers but closely controlled their editorial and political line as well, and turned them, by constant and even daily intervention, into vehicles of their personal views.19

As Miliband suggested, newspaper owners have bought them not only because they have been highly profitable businesses - “rivers of gold” in Rupert Murdoch’s words - but also because they confer political influence and social prestige. Their commercial and political uses can be interrelated, as in the case of Rupert Murdoch, who has always understood the business value of political influence. Support from Margaret Thatcher helped smooth the path to his takeover of the Times and Sunday Times in 1981 and aided his establishment of Sky TV; support from the Reagan administration and its FCC helped him break into the US TV market; successive Australian governments have dismantled media ownership rules allowing him to own more newspapers and TV stations there. Murdoch’s titles are frequently used as the public arm of his lobbying effort. One thing a Murdoch newspaper can always be counted on to argue is for cuts to public broadcasters, as rivals to his TV companies.20

The impact of elite ownership of media is huge, and Corbyn’s speech was right to focus on it. However, what analyses of the commercial media often miss is the bias created by private consumption of news media. This occurs in two fundamental ways. First, the wealthier a newspaper’s audience is, the higher cover or subscription price they can pay, and the more attractive the paper’s audience to advertisers. Moreover, since, in a capitalist society, the wealthiest tend also to be the most powerful and influential, corporations and wealthy individuals seeking political influence have often been most prepared to subsidise those news outlets aimed at wealthy audiences: the Times has long been run at a loss in a way Rupert Murdoch has never let the Sun be.21 In this way, the media of the wealthier classes is triply advantaged over the media the working class can afford: not only are they able to charge higher prices and collect more advertising revenue, they have often benefited from private patronage too.

As a consequence, newspapers aimed at the wealthy are generally able to do much more news origination than working-class titles: ‘quality’ papers have usually had several times more journalists working for them. In a very basic sense, the production of news is heavily biased towards the kind of news that is likely to interest and appeal to the wealthiest in society. Those superior reporting resources also tend to lend them more authority in society, becoming regarded as the paper ‘of record’, and the default sources for deciding the agenda of broadcast news programmes like Today or Newsnight.

Their influence is in huge disproportion to their circulation, and also to their real merits: the mere fact that the Times employs a large number of journalists cannot offset the fact that those journalists are working to a Murdoch editorial formula that takes the paper’s output far from journalistic ‘quality’ as it is usually conceived.22 The belief that these newspapers ought to be trusted because they are old and established, read by the educated and well-off classes, and well-resourced, is wrong. The Times has consistently proven that it stands ready to publish false or misleading stories when it suitsthe assumed views of its readership, or the agenda of its owner. The recent smears against Corbyn for being a ‘Czech spy’ are one example. The recently upheld complaint against it for its coverage of a young girl’s foster placement with a Muslim couple is another.

The second bias created by private consumption is, broadly speaking, in favour of personal satisfaction and against public benefit. As private consumers, we decide what to buy based on whether the media product will satisfy us as individuals, since it is our own money alone that we are parting with; if, instead, we are making a decision about what our society as a whole ought to spend money on, we are at least more likely to think in terms of the public benefits delivered by different media outlets (even if this cannot be guaranteed). By funding the NHS collectively, we acquire the security of knowing that no matter our personal finances, we will not be refused treatment because of lack of means; clearly, this benefit cannot be delivered by a private market system: it is inherently social. There are likewise inherently social benefits of good journalism, which a media producing for private consumers will necessarily neglect: an informed public; the classic ‘watchdog’ function, performed by investigative journalism in particular; the detection of corruption and crime, especially at the highest levels of society. What made the phone-hacking scandal so explosive was that it revealed not just corruption and crime at the highest levels of society, but that these were rife in precisely the places most responsible for uncovering these things.23 Meanwhile, there are inherently social costs of bad journalism: a misinformed public; the spread of bigotry and prejudice; intimidation, intrusion and harassment; encouragements to violence.

These structural biases and flaws have been compounded by changes to the newspaper industry in the last four decades. From the 1980s onwards, a new wave of concentration occurred in the newspaper industry, in both the UK and the US. Corporate chains acquired large numbers of local newspapers and ran them to the dictates of ‘shareholder value’. Rupert Murdoch’s media empire steadily expanded.24 In Britain, the Murdoch-led move to new printing technology and the resulting destruction of trade union power in the industry (after an epic battle at Wapping in 1986 in which Murdoch was backed by Thatcher’s police) meant the way was open to a massive intensification of exploitation: output expanded dramatically with no real increase in journalists employed to produce it. Nick Davies estimates that while staffing levels in 2005 were slightly lower than in 1985, national newspapers’ output had trebled in size; therefore, time spent on stories had shrunk by two-thirds.25

The print unions were also a constraint, in extremis, on how low newspaper could go, particularly in their coverage of the trade union movement. From the mid-70s onwards, the spectre also threatened of an alliance between unionised printers and journalists to use their collective strike power to secure journalists more editorial autonomy from their editors and owners. That was, of course, unacceptable both to many owners themselves and their allies in the Conservative party. The Thatcher government’s efforts to break workers’ power in the media industry are a neglected dimension of the rise of neoliberalism. Breakthroughs here - particularly Murdoch’s takeover of the Times and the neoliberal reform of the BBC - helped consolidate Thatcherism into the new common sense it became in the 1980s.

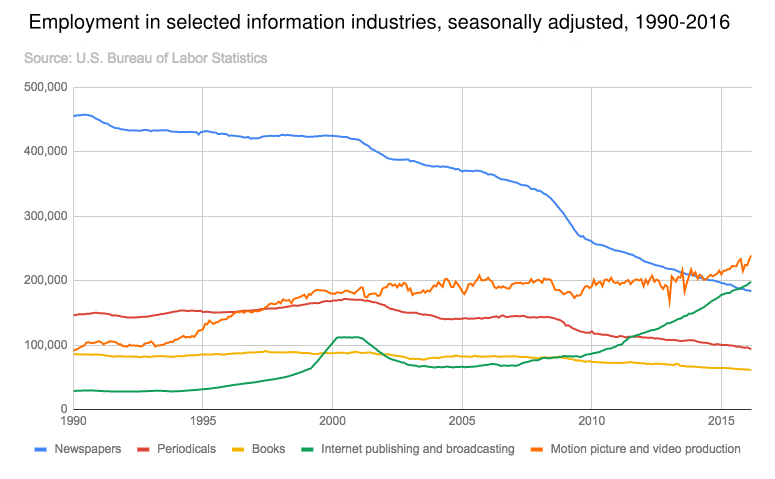

The local press also became much more consolidated in the 80s and 90s. In one year, 1996, a third of all local papers were sold to new owners; by 2005, ten corporations owned 74% of the local press. Today, six companies account for 81% of weekly local and regional circulation.26 The big local chains kept laying off journalists to achieve exorbitant profit margins - Johnston Press’s was 35% in 2004.27 Much the same occurred in America.28 Although the job losses since the financial crisis have been massive, there were huge layoffs before then too, as the chart below shows. Overall, 60% of US newspaper jobs disappeared between 1990 and 2016:

The newspaper industry was being gutted already, but mass adoption of broadband internet in the mid-2000s, and especially the arrival of social media and the mobile internet from the late 2000s onwards, produced a full-blown crisis of commercial news production. As with the flaws inherent in commercial news production, this crisis can be looked at from consumption and production perspectives.

On the consumption side, the internet has created an explosion of consumer choice. Although it began confined to the desktop, from the late 2000s smartphones and tablets took it into locations which print media once had a virtual monopoly - the commute being the most obvious example, but also the bathroom, the garden, etc. These locations have now been permanently opened up to competition from all forms of digital media: not just news, but Facebook, games, YouTube videos, etc. At the same time, the endless content online means people can also consume far more news and comment, if they want.

Unfortunately, there is little data on how the distribution of news consumption across the population has changed over time, but it would be surprising if at least some people’s consumption has not declined, and possibly consumption has declined overall. What we can conjecture with some confidence is that these changes have probably led to a much more unequal distribution of news consumption across the population, with some people becoming more disengaged from the news and others becoming ‘news addicts’. What we can say for certain is that the new ubiquity of the online world has coincided with an acceleration in the rate of newspaper circulation decline almost everywhere. That acceleration has been particularly marked in the US and UK.

The production side, however, presents a truly disastrous picture. Once it arrived, news publishers raced to develop websites and dominate the new online environment. But the commercial production of news requires being able to make money doing so, and the internet has radically undermined both of the traditional ways of monetising commercial news production.

Charging for a product, as in a newspaper cover price or digital news subscription, requires the consumer to be unable to get it for free by some other means. But the most fundamental effect the internet has had is to enable the rapid, free transmission of information. In response, many news publishers have made their sites free to read (which has helped collapse newspaper sales). Because any original news story can now be republished by other news organisations within minutes, the profitability of original news production has collapsed and so publishers are doing less of it. An important part of the job of today’s digital journalist is ensuring their site has a version of any important stories published by their rivals, so their site gets at least some of the traffic. Some sites have gone to the extreme of wholesale, blatant plagiarism.

There has also been a moving away from original reporting and towards publishing more comment, which is more difficult to plagiarise, but also cheaper to produce and more shareable on social media. With so many getting their news from free and immediate sources like Twitter and Facebook, and only secondarily from news websites, the scope for charging readers a subscription fee is limited for many sites. The ones that are able to typically have an elite audience, or business users whose employers pay for their accounts.29

The second traditional source of revenue has been advertising. Previously, newspapers were one of the few ways advertisers could reach a specific demographic within the general UK population: ‘quality’ papers like the Guardian or the Times had small, affluent readerships; local newspapers were another means of sub-national targeting. Yet digital advertising can now be targeted with unprecedented demographic and geographic granularity.

The scale of use of centralised digital services like Google and Facebook - which are also natural monopolies with no content production costs - means those companies have vast amounts of ad space and user data, and hugely superior ad targeting and measurement capabilities compared to news publishers. Between them, they now take over half of digital advertising revenue in the UK. Meanwhile, ‘quality’ news outlets like the New York Times once generated around 80% of their print revenue from advertising, but now their online revenue comes mostly from user subscriptions. The rest of the online news media is competing over comparatively tiny amounts of ad money. Total UK newspaper advertising expenditure was £4.6bn in 2007; today it is £1.4bn, and digital advertising revenue for newspapers online is £487m.30 The collapse of print advertising revenue, and the inadequacy of digital revenue sources, is the central cause of the crisis in commercial news production.

One route out of this massive commercial crisis is simply to run news organisations at a loss. In 2013, the wealthy Graham family, owners of the Washington Post since 1933, decided even they no longer had the means necessary for the paper to survive - i.e. the wealth to run large losses for years - so they sold it to one of the wealthiest people in the world, Jeff Bezos, who promised to give the Post plenty of financial ‘runway’. If news outlets are now to become loss-making entities, the wealth required to own them has just got even greater. We seem to have, as The New Republic put it recently, “an entire industry that is increasingly looking to billionaires for salvation.”

This crisis is so deep that it has led some people to romanticise the state of journalism before the effects of the internet set in. But the account I have outlined above shows why that tendency is misplaced. Even before the current funding crisis, newspapers were being hollowed out by rapacious owners, and were publishing to cater to the biases of ownership and consumption I have described.

Consequently, it is not enough to merely solve the funding crisis. Any socialist media reform programme must seek to replace the private production and consumption of news with something better. It must seek to democratise journalism, to make it publicly funded and freely available, while avoiding the problems of state control that can come with public funding, as demonstrated by the history of the BBC. At the end of this piece I will outline a solution that meets those criteria; before that, I will look at Corbyn’s proposals.

Solutions to the crisis

What solutions did Corbyn’s speech propose to address the failures it identified? Essentially two that will be considered here. First, regulation of private sector media; second, new ways of funding non-profit media: some public, some private. He did make a third proposal that would help journalists, pledging to expand the Freedom of Information Act by extending it to cover private companies awarded public contracts (as already announced), and by ending the ministerial veto. Both of these are welcome changes, but lie outside the focus of this essay, which is the funding and production of journalism. I will therefore focus on the first two proposals.

Corbyn’s speech proposes legislation requiring privately owned news outlets whose audience exceeds a given threshold to allow their journalists to democratically elect their editor. Above a second, higher, audience threshold, they would also have to appoint representatives of both their journalists and their audience to the company board. The apparent aim is to sever the link between ownership and editorial control over news outlets. Leaving aside potential practical problems - how audiences are measured across platforms, how audiences are aggregated across titles owned by the same publisher - this raises the question, what if these proposals are successful in severing that link? The attraction to many wealthy individuals and major corporations of owning news outlets would surely be reduced. Control over editorial production is, after all, central to any commercial strategy. Then there is the political influence, itself of immense commercial value as already outlined, that some proprietors like Rupert Murdoch derive from being known to exercise de facto editorial control over their titles.

What these proposals do not do, however, is challenge other important prerogatives of private ownership, like the right to vary investment, and to sell or close the outlet. If the journalists working at, say, The Times, elect an editor Rupert Murdoch regards as unsuitable, he could retaliate by cutting investment, forcing the editor to lay off journalists. Alternatively, he could threaten to close or sell the paper. These implicit threats are likely to strongly influence journalists’ choices. In fact, what Corbyn’s proposals do is replicate the relationship between capitalism and democracy in microcosm, within the news outlet: the private control of investment enables the capitalist class to, in effect, ‘veto’ governments they dislike with investment strikes and international currency movements; in a similar way, owners of news outlets would be able to use their economic power to exercise a ‘veto’ over editors they dislike.31

The proposal doesn’t tackle the consumption side of the problem with commercial news media, nor does it address the crisis of production. There is no evidence that the reactionary garbage produced by the Daily Mail is the consequence of its owner’s editorial influence; rather, Jonathan Harmsworth gave Paul Dacre the freedom to edit the paper the way he did because it proved a highly profitable formula. That formula will remain profitable whether the editor of the Daily Mail is elected or not. The profitability of the paper determines whether journalists are hired or laid off, their pay and their working conditions. In this basic sense, then, journalists have immediate interests which are closely tied to the commercial success of their title. That naturally limits their preparedness to elect an editor who will deviate from the Mail’s profitable editorial formula. Meanwhile, class inequality in the addressable market for news will continue to produce a media overwhelmingly biased towards the affluent for the reasons I have already explained. Then there is the fact that age differences in where people like to get their news from will continue to encourage newspapers to cater to older age groups.

The second major set of proposals in Corbyn’s speech are all essentially new ways of funding non-profit media. The first idea, making them eligible for charitable status, seems good and unobjectionable, but how much of a difference will it really make? It still leaves non-profits dependent on a mixture of donations, grants and tax exemptions. Reliance on donations and grants leaves news organisations particularly dependent on the wealthy, and on the philanthropic foundations of the very rich. Nor is there any evidence that donations are going to come close to compensating for the billions a year lost by commercial news producers, much of which is simply not going to return because the changes which have caused that loss are technological, and irreversible.

The second, more interesting, funding proposal is to introduce a new public fund for journalism, paid for by the tech giants. Here, Corbyn’s speech effectively delivers an ultimatum: either Google and Facebook give up the money voluntarily, as with Google’s agreement with French publishers, or a Corbyn government will impose a windfall tax on them. This immediately raises two questions: first, how much money will such a mechanism raise? Second, and more fundamentally, who decides how the money will be allocated?

Corbyn’s speech highlighted the example of Google’s settlement with French publishers as a possible precedent, but the size is not encouraging: €60m in 2012. Meanwhile, Google’s main voluntary initative to fund news producers, its ‘Digital News Initiative’, is paying out €150m to publishers across Europe across three years. That’s €50m a year for an area of over 700 million people. Contrast that to the roughly $6bn in digital search advertising revenue in the UK alone by the end of 2018 - most of which will be taken by Google and Facebook. The example of these ‘voluntary’ initiatives, which in reality do the bare minimum to placate publishers, show that a voluntary agreement is unlikely to get anything like enough money out of Google. We ought to be setting our sights much higher than these sums: a large windfall tax would be much better than a voluntary agreement.

More fundamentally, funding a major expansion in new public media should be a major political objective of a socialist government. We should therefore consider it a funding priority. Unless we reduce the power of the neoliberal right in the media sphere by developing publicly funded journalism across the country on a large scale, we will find any remotely socialist government facing a barrage of hostile propaganda, misinformation and smears. And our objectives in countless areas require a new journalism more interested in, and capable of, reporting accurately and honestly on what is happening in our country.

We cannot hope to regenerate local democracy without a massive expansion in local news production. To sustain any advances we might make in unionisation and trade union power, the appalling bias on display in the reporting of labour disputes has to end. We need a new wave of journalism dedicated to exposing what is going on in privately-run prisons; what is being done to the NHS; the links between politicians and private companies; who funds pro-free-market think-tanks. We need a journalism that does the basic job of educating the public by honestly and conscientiously reporting issues like climate change, immigration and crime in ways that lead people to understand these problems in all of their complexity. We are not going to get any of these things without major reform. The Thatcher Government used neoliberal reform of our media to embed a new political consensus; our programme ought to be driven by the same ambition.32

On the second issue, of the allocation mechanism this proposed new public fund would use, Corbyn’s speech is silent. However, the speech also mentions the BBC’s ‘Local News Partnership’ scheme, and suggests that money from the scheme, which until now has mostly gone to three large commercial publishers, ought instead to be “made available to local, community and investigative news co-ops, with a mandate to use significant time and resources reporting on public institutions, public service providers, local government, outsourced contractors and regulated bodies.” This would be an improvement over the current BBC scheme, which is allocated by unaccountable senior BBC editorial figures, and effectively uses the licence fee to subsidise commercial news production.33

It seems as though the speech envisages allocation by some kind of grant-awarding body established by the state, on the model of the Arts Council or the BBC itself. Yet elsewhere, Corbyn’s speech proposes democratising the BBC, acknowledging the public should have a direct say in the running of our media institutions - something also implied by the proposal to have audience representatives on the boards of major news outlets.

Labour should be bolder. It should propose abolishing the BBC local democracy reporter scheme entirely, and using the licence fee to fund a democratised BBC, not commercial publishers. Alongside that, Labour should propose to establish a single public fund for non-profit news outlets, funded by the proposed tax on the tech giants’ digital advertising revenue and also by general government revenue. The fund should be allocated by the public, democratically, at regular intervals. The best way to do this would be by establishing a voucher system.

A voucher system to democratise journalism

Under this scheme, each member of the public would get a voucher worth a defined amount of public funds, which would only be able to be ‘spent’ by being divided up among any number of news outlets that meet defined criteria. Each voucher could also be divided into ‘local’ and ‘national’ segments. Outlets wanting to compete for funding would have to decide whether to compete in a particular locality or region, or in the national competition. In this way, the existence of both new local and national media would be guaranteed. Some basic criteria outlets should meet to be eligible are:

- All journalism funded this way must be freely available online, whether in written articles, graphics, video, podcasts or other forms.

- Participating outlets cannot carry any advertising.

- All outlets would have to be non-profit co-operatives with democratically elected editors, in which there is trade union recognition.

- All outlets would have to be a member of an adequate standards regulator, which would also monitor participating outlets’ financial probity.

There are many major advantages of this system. First, it would remove control over funding from both the central state and appointed representatives of it (such as the members of the Arts Council or the major research councils), enabling journalists to take on the state without fear of losing funding - a critical problem with the BBC (and a crucial reason why its governance ought to be democratised and control over its funding taken out of the hands of ministers).

Second, and just as importantly, it would require journalists to establish and maintain a direct relationship with the public. It is a major problem with grant-funded journalism that it imposes no equivalent discipline on the journalists it funds. Indeed, many grant-funded entities like the Bureau of Investigative Journalism - whom Corbyn lauds in his speech - partner with established media organisations to get their stories noticed. Under a voucher system, only media organisations that develop and maintain strong, direct connections to the public would receive funding.

Third, by giving each person the same sized voucher to award, this system establishes the principle that each citizen ought to have the same influence over our media. It would represent a clear and concrete extension of the public’s democratic rights - in this case over media institutions - while handing them precisely the sort of ‘choice’ which, until now, the neoliberal right has always been able to claim as a decisive advantage of private over public provision of goods and services.

As well as many other advantages, there are undeniably a number of challenges that would have to be overcome. However, the same broad idea has been proposed by the American radical media scholar Robert McChesney.34 But the more we use something like this system to fund our media, and the less we leave it to the market to provide our news, the more the goals Corbyn’s speech sets out will be achieved: our media will be more diverse, more controlled by journalists themselves (while making them directly accountable to the public for their performance), and less controlled by the wealthy. Of course, precisely because it would have these effects, the introduction of such a system would face the most concerted resistance from those who would lose out from it: the wealthy and their ideological representatives. It is a fight we must have, and which we can win.

-

Which all 175 of his newspapers across the world supported and which cemented Fox News as the number one rated US TV news channel. ↩

-

Only a backbench rebellion of Labour peers in the Lords led by David Puttnam ensured New Labour’s 2003 Communications Act did not remove all barriers to Murdoch acquiring more of our broadcast media, by inserting a clause protecting media plurality which has turned out to be crucial in blocking the takeover of Sky News by Fox. ↩

-

Labour’s main proposals in this period were: a commitment to implement the recommendations on press regulation contained in the Leveson Report; some tentative proposals to cap media ownership in ways that would probably have forced Rupert Murdoch to sell either the Sun and Sun on Sunday or the Times and Sunday Times; a commitment to hold Part Two of the Leveson Inquiry. ↩

-

As the merger inquiry’s web page shows, the only Parliamentarians to take up the matter in a concerted way was a cross-party group of politicians: Ed Miliband, Charlie Falconer, Vince Cable and Ken Clarke. All Watson has done is turn up to respond to the Culture Secretary’s Parliamentary announcements on the bid - as he is required to. ↩

-

An endeavour in which they have been aided by Damian Collins, the Conservative chair of the Digital, Culture, Media and Sport Select Committee, who has tried to use ‘fake news’ to redirect the debate over media reform away from press regulation, as in his column, “MPs should be targeting fake news - not the free press”, The Telegraph, 6 January 2017. Matt Hancock adopted much the same line in his time as Culture Secretary. ↩

-

See the table on p. 6 of the Mediatique report. Note that there were also massive layoffs in the 1990s and early 2000s by the major local publishers, addressed in more detail below. ↩

-

Noam Chomsky and Edward Herman’s classic Manufacturing Consent (1988) is particularly good on the sourcing of news from government and corporate sources. See esp. p. 18-25. Nick Davies’s Flat Earth News (2008), especially part three on the reliance on PR and government sources, shows how bad the situation was in Britain even before the collapse of the last decade. ↩

-

This was all described in detail in Nick Davies’s 2008 book Flat Earth News; the problem has existed for a long time, but has got worse over the last decade. ↩

-

Other news media also performed poorly. For the ease with which The Observer’s political editor Kamal Ahmed, now the BBC’s economics editor, was manipulated by Alasdair Campbell into propagandising for the Blair Government, see chapter 9 of Flat Earth News. The fawning coverage on the day of the invasion by the BBC’s political editor at the time, Andrew Marr, is also infamous. For Panorama’s deference to official sources, see David McQueen, “BBC’s Panorama, war coverage and the ‘Westminster consensus’”. Westminster Papers in Communication and Culture. 5(3) (2008). See also Tom Mills, The BBC: Myth of a Public Service (2016), chapter 3. ↩

-

See Simon Wren-Lewis’s 2015 LRB essay “The Austerity Con”, and also his blog posts on ‘mediamacro’. ↩

-

For a detailed analysis of media coverage during the campaign, see this report by KCL’s Centre for the Study of Media, Communication and Power, which found that immigration was the most prominent issue in the campaign, and that “Coverage of the effects of immigration was overwhelmingly negative. Migrants were blamed for many of Britain’s economic and social problems – most notably for putting unsustainable pressure on public services. Specific nationalities were singled out for particularly negative coverage – especially Turks and Albanians, but also Romanians and Poles. The majority of negative coverage of specific foreign nationals was published by three news sites: the Express, the Daily Mail, and the Sun.” (p. 9) ↩

-

See Robert McChesney and Ben Scott’s 2002 essay on Sinclair’s book, “Upton Sinclair and the Contradictions of Capitalist Journalism”. ↩

-

This chart is taken from p. 36 of the US Federal Communications Commission’s 2011 report, “The Information Needs of Communities”. Its section on commercial newspapers gives a good brief history of US newspapers and includes much good data. ↩

-

In fact, if one of the reasons our media is so concentrated is because consolidation generates efficiencies that improve profitability, then dispersing ownership might just mean several smaller, less profitable companies. If news outlets are less profitable, or even heavily loss-making, there is no real reason to see why they will be less likely to be owned by the wealthy - indeed, the lower profitability goes, the wealthier owners will need to be to cover the losses. ↩

-

At least as far as their news coverage goes; comment is another matter. ↩

-

E.P. Thompson, The Making of the English Working Class (2013 [1963]), p. 739-40. ↩

-

James Curran and Jean Seaton, Power Without Responsibility: Press, Broadcasting and the Internet in Britain (2010), p. 27. ↩

-

Indeed, it was this development that meant the British state could stop using repressive measures against newspapers, like taxing the press to reduce its availability to the working class, and pursuing radical journalists and publishers with oppressive libel laws. For more on these, see Power Without Responsibility, chapters 1-3. ↩

-

Ralph Miliband, The State in Capitalist Society (1969), p. 166. ↩

-

See the submission made to the CMA’s inquiry into the Fox bid for Sky by Ed Miliband, Charlie Falconer, Vince Cable and Ken Clarke, p. 49-76. ↩

-

The most obvious exception to this is Murdoch’s tabloid and loss-making New York Post, which has for a long time given him influence in New York politics; influence that turned out to be crucial in getting the Fox News Channel going (see chapter 13, “The Right Kind of Friends” in Gabriel Sherman’s 2014 book on Roger Ailes and Fox News, The Loudest Voice in the Room.) But set that against his longstanding subsidy of The Australian, The Times and The Weekly Standard, a neoconservative magazine he launched in the late 90s, ran at a large loss through most of the years of the Bush administration, over whom it was influential, and then sold in 2007 when he acquired the bigger and more influential right-wing organ The Wall Street Journal. The New York Post also gave columns to many prominent neoconservatives. See David McKnight’s Murdoch’s Politics (2013), chapter 3, “At the barricades of the Reagan Revolution”. ↩

-

A number of important consequences flow from this consumption bias: right-wing owners are more likely to do well in the newspaper market because the most lucrative audiences are, broadly speaking, on the right too. It takes no journalistic genius or courage to publish or work for newspapers which confirm the affluent and the very wealthy in their prejudices about themselves and others. For the impact of Murdoch’s acquisition on the Sunday Times’s investigative journalism team, Insight, see chapter 8 of Flat Earth News. ↩

-

The phone hacking scandal was a striking omission from Corbyn’s speech. The best book the scandal is by the reporter who uncovered it: Nick Davies’s Hack Attack (2014). ↩

-

Having acquired hegemony in the Australia newspaper market in the 1950s and 60s (his titles now account for roughly 70% of circulation there), he bought the News of the World in 1968 and the Sun in 1969. His breakthrough to extraordinary power, however, came with the acquisition of the Times and Sunday Times in 1981, with some help from the Thatcher government. In 1976 he had acquired the liberal New York Post and rapidly turned it into a neoconservative mouthpiece. 20th Century Fox was acquired in 1985; Fox Broadcasting founded in 1986; HarperCollins acquired in 1989. The Weekly Standard, an elite neoconservative weekly influential with the Bush administration, followed in 1995, and the Fox News Channel in 1996. In 2007 he sold the Weekly Standard and acquired the Wall Street Journal. ↩

-

Flat Earth News, p. 63. ↩

-

Mediatique Report for the Department of Culture, Media and Sport, p. 12. ↩

-

Flat Earth News, p. 64-5. ↩

-

For an account of the process in the US, see the FCC’s “The Information Needs of Communities” report, p. 36-38. For a ground-level account of the effects by a former journalist, see the testimony of David Simon, creator of The Wire, to the US Congress in 2009. ↩

-

Today, the vast majority of subscriptions to the Financial Times - which costs £278 a year - are corporate. The website of Politico Pro speaks for itself. ↩

-

See the Mediatique Report’s table on p. 6. ↩

-

See Fred Block, “The Ruling Class Does Not Rule: Notes on the Marxist Theory of the State”, Socialist Revolution (1977). ↩

-

For instance, see Peter Goodwin’s Television Under the Tories (1998) for Thatcherite efforts to reshape British broadcasting. For neoliberalism at the BBC, see chapter 5 of The BBC: Myth of a Public Service. ↩

-

It was objected to by the National Union of Journalists on precisely those grounds when it launched. See also the analysis of the CEO of IMPRESS, Jonathan Heawood: “Why is the BBC giving licence fee cash to the companies who have slashed local journalism?” ↩

-

See his 2010 book with John Nichols, The Death and Life of American Journalism, p. 201-6. Chapter 4, ‘Subsidizing Democracy’, contains a range of useful proposals and the book as a whole deals effectively with a range of obvious criticisms. ↩