Bhagat Singh was executed by the British in Lahore) when he was only 24 years old, yet his remarkable political life has continued to prove an inspiration

The Indian revolutionary Bhagat Singh (1907-1931) was executed by the British in Lahore (in contemporary Pakistan) when he was only 24 years old, yet his remarkable political life has continued to prove an inspiration for activists in the Indian subcontinent. Chinmohan Sehanavis writes, “Bhagat Singh and his colleagues sent a telegram to the Soviet Union on November 7, 1930, greeting the Great Russian Revolution. … in January 1930, to commemorate “Lenin Day”, they entered the Courtroom wearing red scarves and demanded that their greetings should be intimated to the President of the Third International.” Even with his approaching death he had a great curiosity about developments in Russia, and is reported to have been reading the work of Trotsky, Lenin, and others in prison, alongside reading of revolutionary struggles in other parts of the world. He surreptitiously passed word to his organisation, the Hindustan Socialist Republican Association (HSRA), suggesting Prithvi Singh be sent to Soviet Russia, to observe the processes therein (ibid). By the time Prithvi Singh made this trip, Bhagat Singh was long gone. It is reported that when asked about any last wishes prior to his execution, “he replied that he was studying the life of Lenin and he wanted to finish it before his death (ibid).”

In this article1 I will try to present some snapshots of the early communist movement in colonial India and its interconnections with global struggles, then refer briefly to the legacy of the 50 year old Naxalite movement in India, before spending the remaining bulk of the essay on a survey of the discussions around 100 years of the Russian revolution in Kolkata, in the state of West Bengal. While the revolution is usually narrated with reference to Soviet history, or even specifically with reference to the developments in Petrograd, in trying to locate it as a “world-historical” event this piece looks at the revolution through certain Indian contexts. Writing seventy years after India’s independence from British rule, in the first quarter I have tried to highlight how intimately the Russian Revolution became a part of the struggle against empire in the early twentieth century. In the second and shortest section I discuss the legacies of the 1967 uprising in Naxalbari, which developed a different lens for reading and carrying forward the legacies of October 1917 2. Since I have not come across much reporting in English from the USA/UK which discusses the public nature of commemorations of the Russian revolution, beyond brief glimpses of some rallies the world over – in the second half I focus on one city in India to show how here the event is being remembered through rallies, speeches, little magazines, books, online publications, lectures, public exhibitions and statues.

The Russian revolution and colonial India

Suchetana Chattopadhyay writes, while studying the primarily negative early press the revolution received in India, that “In the course of November 1917, the colonial world became gradually acquainted with Bolshevism through hostile news networks based in the West.” While the intent in doing so may have been to discourage Indian nationalists and revolutionaries from developing an interest in Russia, it was by no means entirely successful. In the early 1920s, a young landlord (zamindar) in colonial Bengal went on a trip to some of his properties in Patisar (a village in the district of Naogaon, in contemporary Bangladesh), and reported the following conversation. Having reached the remote village, he found himself amongst peasants who made him feel he had “returned to medieval times.” In the middle of the conversation, suddenly an elderly peasant stood up and said:

Babumoshai, talking too much on these issues leads to talking nonsense. The youngsters of the swadeshi [nationalist] movement only give tall speeches about the improvement of the country. They are nowhere to be seen when it comes to doing the actual work. Yes, if a man like Lenin was born in this country, then everything would become alright 3.

Arun Shome 4, discussing the contexts in Bengal, writes that favourable reportage of the revolutionaries had started long before the October revolution, at least from the early 20th century, and included biographies of Narodniks and Nihilists, as well as Bangla translations of texts, such as Leroy Scott’s work on Vera Sazonova. Suchetana Chattopadhyay writes that “In the Calcutta offices of the Intelligence Branch, ‘Weekly Bolshevik Reports’ were maintained during the late 1910s and the early 1920s. A special post was created; the ‘Anti-Bolshevik Officer’ was authorized to detect and monitor signs of Bolshevik activities at the provincial level (2011, 119).” The fascination with the particular figure of Lenin also started early. Ashok Chattopadhyay lists at least 14 “items” of publication in Bangla, from 1917 to 1924, dedicated to Lenin, with the longest single item in the list including five separate monographs on him (36-37).

(A statue of Lenin in Jadavpur, Kolkata (erstwhile Calcutta), that was decorated with lights and flags around November 7th, 2017)

Depending on who you ask, the Communist Party of India was formed in Tashkent, Afghanistan in 1920 5, or in Kanpur, Uttar Pradesh, in 1925 6. One of the founding figures of the party in Afghanistan, M.N. Roy (1887 – 1954), would also subsequently become one of the founding members of the Communist Party in Mexico. Curiously, the house where he stayed in Mexico City is currently a private club that still bears his name!

(I tried to ring for him in Mexico City in 2016, almost a century too late! Here photographed in this futile attempt by Tanima)

John P. Haithcox writes about him, while discussing “The Roy-Lenin Debate on Colonial Policy” 7 that:

BEFORE the opening of the Second World Congress of the Communist International (July 19-August 7, I920) … Lenin prepared a draft thesis on the national and colonial question. M. N. Roy, a young Bengali attending his first international Communist gathering, eagerly responded to Lenin’s request for criticisms. As a result, Lenin invited him to write an alternative thesis. Both theses were modified as a result of discussions within the National and Colonial Commission, and both were subsequently adopted by the Congress. After his encounter with Lenin, Roy rose rapidly in the Comintern hierarchy. In I922 he was elected a candidate member of the Executive Committee of the Communist International (ECCI), and a full voting member in I924. He became a member of the Presidium in I924 … In February of [1926] he was appointed to the editorial staff of the Communist International, and in the following December he was reelected to the Presidium and joined the Political Secretariat of the ECCI. At the time of the Seventh Plenum of the ECCI (November 12-December 16, I926), Roy became Secretary of the Chinese Commission, a post he held jointly with Petrov, and a member of the Agrarian Commission. The Plenum, convened for the purpose of considering the China problem, adopted a thesis on the question and Roy was sent to China as a representative of the Comintern to carry it out.

While it will not be possible here to discuss in detail the specific and substantial contributions made by M.N.Roy to the discussion8, nor how the Russian revolution was enabling for him (or for that matter any of the other figures mentioned herein or not), nor the various internal critiques of Roy by Indian revolutionaries such as Muzaffar Ahmad (1889-1973) 9; the potted references to this early history are meant to highlight primarily two things: firstly, how the repercussions of the Russian revolution in India were intimately tied with the struggle against British colonialism; and secondly, that in order to understand the revolution as a world-historical event it is important to understand how it developed and changed form in interaction with the colonised countries. This latter may seem like an obvious point to be making, yet narratives of the Russian revolution continue to be dominated by discussions of relations with European powers, and contexts such as those in India tend to merit merely a separate ghettoised chapter discussing the derivative effects on India of the revolution elsewhere.

It is notable in this context that the Communist Party of Great Britain (founded in 1920), in accordance with Comintern policy on this question (as discussed above), was a supporter of the struggle against British imperialism from the very early stages. Aside from them, as far as British parties go, it was only in 1931 that the Independent Labour Party’s New Leader took up the cause, and that too in a version very friendly (and simultaneously, of course, condescending!) to M. K. Gandhi, whose bourgeois complicities were highlighted by the CPGB’s Daily Worker from when it was founded in 1930. The Daily Worker further tried to move beyond nationalistic questions of British rule over India, to an analyses of imperialism 10. Two British communists (Ben Bradley and Philip Spratt) were among the 31 arrested from different parts of India as part of the Meerut conspiracy case trials of union organisers and working class leaders in 1929-1933, and a third Englishman, Lester Hutchinson, was soon added to the list. Suchetana Chattopadhyay writes that

Indian connections with the British Communist Party and attempts by communists to organize Indians in Britain, particularly sailors, were closely observed [by British intelligence]. London sources recorded the emergence of a ‘red’ Indian Seamen’s Union (ISU) at the initiative of C.P.Dutt [elder brother of R.P.Dutt], [Nathalal Jagjivan] Upadhyay and [Shapurji] Saklatvala. … Ships arriving in Indian ports were regularly searched and continued to yield ‘results’ in the form of proscribed communist literature (218).

Yet, while noting the important role of Indians inside the CPGB, and CPGB help for Indian communists, it must not be overlooked that at this point the Communist Party of India, much to the chagrin of M.N. Roy and others, was under supervision of the Communist Party of Great Britain’s “Colonial Department”, which risked replicating all too closely colonial structures of authority (Stephen Howe 1993, 63; and by Sobhanlal Datta Gupta in his contribution to EPW’s special issue on 100 years of the revolution, pp.96-97).

50 years of Naxalbari

Within the long history of communist organisation in India, this year also marks the fiftieth anniversary of the ongoing Naxalite movement. The Communist parties came together with Bangla Congress in the 1967 United Front government in the east Indian state of West Bengal. Shortly thereafter, an uprising in Naxalbari, northern West Bengal, in May 1967, contributed to the breakup of the Communist Party of India (Marxist) in 1969, and led to the formation of the Communist Party of India (Marxist-Leninist). This movement, also inspired and subsequently endorsed by Mao 11, was initially called “Naxalite” by newspapers, in reference to the 1967 uprising. It soon spread from a primarily adivasi (“tribal”) and lower caste inhabited region close to the Nepal border to other parts of India, including in the initial phase West Bengal, Andhra Pradesh, Bihar, Assam, Tripura, Uttar Pradesh, Kerala, Tamil Nadu, Himachal Pradesh and Punjab 12, but was brutally crushed in most places by the early 70s 13. Since then it has splintered into numerous parties and groups, the largest of which today is the Communist Party of India (Maoist). According to government statistics released in 2008, CPI (Maoist) alone was active in or had territorial control of approximately thirty three percent of India’s districts 14, though their territorial reach is said to have diminished since.15 All of these different parties, including some who now participate in elections, are referred to (by themselves and/or others) as Naxalite.

(To the right of the frame is the memorial to the 11 murdered by the police on 25th May, 1967, which served as a trigger for the uprising in Naxalbari. This memorial was erected in 1978 in Bengaijote, Naxalbari, under the leadership of Khokon Mazumdar (one of the founding figures of the movement, born Abdul Hamid, 1931 – 2017), near the place where the 11 were shot. Later, some followers of a different Naxalite faction installed the other busts, beginning with Lenin and Stalin. This produced the odd circumstance where the 8 women, two unnamed children and one young boy who were killed in Naxalbari are in effect crammed into one memorial, while other figures get a separate bust to themselves. As a result, in the narrative framed by the busts, important foreign and upper caste Hindu male leaders involved in the movement take more space than the primarily lower caste and indigenous women who lost their lives near that spot. What Sudipta Kaviraj argues more expansively is certainly very applicable to some strands of the Indian left: they are often too immersed in understanding local struggles through reference to Russian or Chinese events/authors, in a process of erudite brahminical textualisation of the political realities they are immediately faced with (2007). Yet this represents only one strand of the developments, and though this memorial is very frequently photographed by journalists reporting on the region, those surviving participants of the 1967 uprising who I have spoken to during fieldwork didn’t seem very happy with certain aspects of this lopsided emphasis. The site still says something about the event’s memorialisation that is important to note, though I could have used numerous other photos from the Naxalbari region of graffiti and sculpture celebrating the Naxalite movement, which have no reference to Lenin or Stalin.)

Naxalbari marked an important moment in provoking new approaches to organising. At a time when Mao’s influence registered all the way from French intellectuals to the Black Panthers, a segment of India’s revolutionary left were also inspired by the developments in China. This encouraged a fresh questioning of models of politics inherited from Europe, and also of the Soviet project.

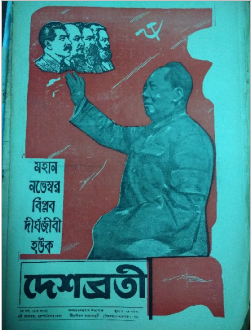

(18th issue of the weekly Deshobroti, dated 9th November, 1967. It would go on to become the official Bangla organ of the newly formed CPI-ML. This issue, marking 50 years of the Russian Revolution, is titled “Long Live the great November Revolution,” but note how Mao figures in relative emphasis to Marx, Engels, Lenin and Stalin.)

(Khudan Mallick, here photographed at his place in Rambhola jote, Naxalbari, this October, remained organisationally active till his death last month. He was the last surviving member of a four people Naxalite delegation that met Mao Zedong in China in December, 1967, towards the end of three months of training. Mao reportedly advised them: “Forget everything you have learnt here in China. Once back in Naxalbari, formulate your own revolutionary strategies, keeping in mind the ground realities over there (Bappaditya Paul, quoting Kanu Sanyal, 2014:130).”)

(Shanti Munda at her residence in Sebdella jote, Naxalbari, in October 2017. Veteran leader of the movement, also a participant in the 1967 uprising, she continues to be organisationally involved)

Within the Indian left, the Naxalite organisations today are usually distinguished from a host of left parties that together form the “Left Front” electoral coalition: in practice the lines can be very sharp or blurred, or the binary may not help understand the configurations, depending upon the context. The Communist Party of India (Marxist), or CPI-M, is the largest party within the Left Front, and has led the government in the state of West Bengal for a continuous period of 34 years, from 1977 to 2011, and is presently the largest party in the state legislatures of Kerala and Tripura (for context: presently the Hindutvavadi right wing Bharatiya Janata Party is in power in 18 states, and the largest opposition party in terms of parliamentary numbers, the Indian National Congress, is in power in 4 states).

November 2017 in Kolkata, West Bengal

(While the loudspeakers everywhere ensured audibility, the podium can hardly be seen at the front, given the crowds at the SUCI (C) event to commemorate the Russian revolution, held in Kolkata on 17th November; behind the trees one can glimpse a floodlight at the Eden Gardens, where day 2 of the men’s cricket test match between India and Sri Lanka was largely washed out by the rains)

(A closer view of the podium at the SUCI(C) event)

Within these contexts, November found me in Kolkata, conducting doctoral research (on the Indian left in the 1970s and 80s), and gave me the opportunity to attend a number of events dedicated to the Russian revolution, while collecting and reading a range of publications on the subject. The largest of the events I encountered, in terms of participation of people, was a “mass meeting” organised by the Socialist Unity Centre of India (Communist) (SUCI (C)). Featuring large paintings of Lenin and Stalin next to the podium, and a stage of full of elderly men, the substance of the one lengthy speech that comprised the event was predictably not too exciting. It was a long narrative of the events in Russia, without any fresh criticism or suggestions about ways forward. To their credit – aside from the large mobilisation of people from different districts – they had also prepared a lengthy tri-lingual exhibition along the side of the road, including photographs, quotes and narrative. I collected seven publications (in English and Bangla) dedicated to the October revolution from their book stalls at the event, which were selling material in at least four different languages. Workers’ Voice, the organ of All India United Trade Union Centre, labour wing of SUCI (C), had this to say on its first page, after quoting Stalin for most of the preceding paragraph:

[The Soviet government] created a society free from starvation, poverty, unemployment, illiteracy, religious bigotry, casteism, racialism, sex-discrimination, minority oppression etc. all evil vices and narrow, backward thinking of all previous social orders.

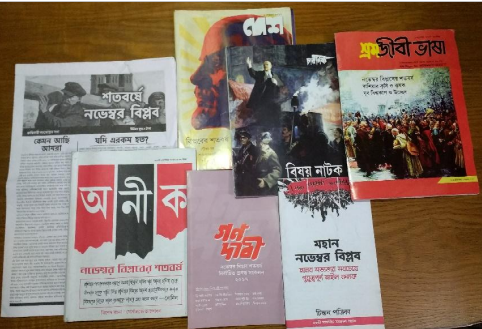

And so on, about utopia on earth, how until Stalin’s death everything was on track, etc. After this lengthy opening essay, the publication includes some documents from the archives, an essay on the celebrations conducted to mark 100 years of the revolution, and other reports about organising around the world. Continuing in this Stalinist vein, Youth Vanguard, organ of All India Democratic Youth Organisation, SUCI (C)’s youth forum, began its publication with “Great Stalin’s Speech.” SUCI (C) also published a book as the party. This aside the four Bangla publications16 were: Charonik’s special issue with plays on the revolution, Gono Dabi published a collection of essays from different periods on the Russian revolution, Pothikrit published a collection of essays, Jhor published a special issue of their magazine.

On a more exciting note in terms of offering fresh political perspectives, the little magazine Aneek, prominent since the late 60s for highlighting voices from a broad spectrum of the revolutionary left (though it has varied in its leanings over the years), published a special issue on the November Revolution. It included articles studying the contexts in Russia, articles on the early communist movement in India, and two other articles that I have already cited above. The more mainstream Bangla literary magazine, Desh, also published a special issue on the revolution. The prominent historian Gautam Bhadra wrote one of the three articles, striking a very critical but sympathetic note. He spoke of the persistence of an authoritarian state in Russia (its failure to wither), the collapse of dreams in China (with its transformation into an aggressive capitalism) and elsewhere, and how this had made people wary of dreamers – yet, he ends on an uplifting note, these slogans of bygone days can still potentially spark some future! One commonality for all the articles in Desh on the Russian revolution is some reference to Rabindranath Tagore (1861-1941), who won the Nobel Prize for literature in 1913, becoming the first non-European to do so 17. In school while writing exams we often contemplated inventing quotes by Tagore to justify whatever we were arguing, and unfortunately sometimes these essays fall into that pattern. A very important and powerful writer as Tagore was, here he occludes many other interesting voices that one could cite in his place. In this regard, Arun Shome’s stand-alone essay on “The Bolshevik Ghost and Rabindranath” in Aneek’s November issue is more helpful. Beginning with a longer history of the vilification of Russia by the British in India (starting his story in the 19th century), Shome traces Tagore’s deep anxieties about the revolution, and contextualises his qualified praise for it 18.

Yet despite the varied critical approaches to this history in evidence here, these events also offer a testament to the continued and disturbing afterlife of Stalin. Aneek organised a lecture on the difficulties of building Soviet socialism on 20th November, by the prominent Bangladeshi communist writer and activist Badruddin Umar 19. One might have hoped, especially given that subject and the times we live in, that this would have been a good occasion for a considered critique. Instead, Umar spent the majority of his presentation regarding the difficulties of building Soviet socialism on an elaborate defence of Stalin. As a veteran activist who was in the audience summarised it dismissively afterwards: basically, all you need to get to a revolution is Stalin and a bicycle!

Chinton, another magazine of the left, organised a panel with members from different parts of the revolutionary left. K. N. Ramchandran from the Communist Party of India (Marxist Leninist) (Red Star) spoke about their attempts to build international collaboration, the recent struggles against the building of a power grid in Bhangar, and tied this to their party’s reading of the Russian revolution. In discussing Lenin’s contributions, he flagged three specifically: the work in building the Third International, his work on imperialism, and his strategies for revolution. Thereafter he flagged three shortcomings/problems: firstly, the Soviets were weakened and power wasn’t with the workers and people; secondly, the idea that Russia had to “catch up” with imperialist countries, such as U.S.A., and thirdly, that there hadn’t been a larger process of cultural churning in Russia. Speaking before him, Proshanto Ray of Chinton began by stating that before going through a thorough self-criticism it would be remiss to simply celebrate the revolution’s legacy. He spoke of how the revolution had failed to move towards workers’ control with the early weakening of the Soviets, becoming a one-party rule reliant on the bureaucracy, and argued that many of these problems were constitutive/ had started while Lenin was alive, so it would be misleading to simply criticise Stalin for these.

In a somewhat different vein, Tilak Dasgupta agreed with the preceding speakers on the question of criticising one-party rule and the weakening of the soviets, but felt it important to spend more time emphasising all the victories of the revolution. He referred to the persistence of bourgeois propaganda against the revolution, citing three recent articles in the Indian media. Curiously, one of the titles he criticised for “dressing up as a socialist” and calling it the “Revolution Against Das Kapital,” appeared to refer to an article that was quoting Gramsci as saying so in a positive sense 20. The next speaker Subhash Ray, speaking for the magazine “Shondikkhon”, didn’t appear to see much point in forums like this. When will we be free from the cycle of seminars, he asked rhetorically, to a lot of applause from the audience. He referred to Dasgupta five times in his presentation, spoke of the problems faced by the revolution in being incarnated in a “backward” country like Russia, and how in today’s contexts speaking of “revolution” with workers isn’t proving very helpful in organising them.

There were therefore a variety of voices on the panel, coming from different lineages of radical left politics. At one end of the spectrum, Subhash Ray’s position effectively suggests no next steps except more of the same/similar organisational strategies with hopes for better times (if Russia was condemned for being “backward,” what can one do in India?), hardly a novel formulation of the problem (it’s much older than the revolution itself!), and is perhaps evidence of a sense of despair. Nor is this a theoretical quandary affecting simply activists in India – over the course of my three years in England (2009-12) I have spoken with activists of different left groups, in one-on-one sittings, or just having a conversation after a run-in on the streets, who have remarked that with the recent industrial developments in India, there would be an expansion in the working class, and thereby India would be much more central to global revolutionary politics. Sitting in West Bengal, marked by continuing factory closures, it is difficult to see what kind of revolutionary politics such a position allows one to imagine. After going through Russia, China, Cuba, Venezuela, the Zapatistas and others elsewhere, do we again need “advanced” revolutionary saviours!?

I have dwelled on one aspect of the panel in some detail due to the resonances with a lot of ongoing discussions that folks in Britain may be more familiar with – and will hopefully find better local points of reference for. And further to highlight, though it won’t be possible to discuss them further here: firstly, though this argument (about putative backwardness of Russia and hence …) has resonance here, it is one in a spectrum, being discussed among people who are trying to collaborate and critically reflect on each others’ approaches. That in a political world remarkable for its fissiparous tendencies four people from different backgrounds and readings of the Russian revolution would come together for an open discussion in this manner is important! It is a testament to the various (more substantive) collaborations and conversations ongoing between these political organisations that the speakers are involved with. Secondly, and relatedly, away from the realm of these discussions, the actual practice of their politics in this region holds some promise, which merits more attention to their engagement with the legacies of the Russian revolution.

(the all-male Chinton panel, with two moderators and four speakers)

Chinton also published a short book, which was being sold for INR 10 (approx. 0.12 GBP) at the event. However unlike the presentation by its speaker at the event, the booklet doesn’t open the discussion with critiques. Rather, it proceeds with a long narrative of events, which is not particularly exciting for a reader familiar with the overall story, since neither does it use any new sources (it lists only three sources in the bibliography, two of them ancient, and the third being Aneek’s special issue referred above), nor provides any fresh criticisms. Relative to this, the Krantikari Naujawan Sabha’s publication (priced at INR 4, approx. 0.05GBP; and freely available online), is more reader friendly, with an appealing arrangement of short issue-based pieces accompanied by photographs. It does not aim for the long-form essay, which requires a lot to justify its length, and although unfortunately rather uniformly celebratory is nonetheless somewhat informative.

For the preceding paragraphs I narrowed down on some of the organisations that are working most directly or explicitly with the legacy of the Russian revolution, as seen from one city (Kolkata), to give a partial sketch of the spectrum between the more orthodox and heterodox approaches within this fold. To mark the centenary of the Russian revolution, a variety of leftist forces have been celebrating and reflecting on the event; alongside similar processes in mainstream publications, organisationally unaffiliated political publications, academic venues, organisations such as a film clubs (the Eisenstein Film Club, for instance, screened Eisenstein’s October at the Gorky Sadan auditorium), conferences featuring academics and activists in conversation (such as New Socialist Initiative’s seminar in Delhi), through republications of important work (for example, a new edition of selected writings by Alexandra Kollontai, with a foreword by Parvathi Menon) and reprints of Soviet publications in Indian languages (for example, the 1987 Bangla translation of Nikolai Dubov’s 1985 illustrated history of the Russian revolution, printed by Progress Publications 21, Moscow, can be accessed for free now on one of the sites that host Soviet literature in Bangla, and a newly printed version of the text has also been receiving some informal circulation in Kolkata this year). Yet, these mark only a part of the political lineages that have an engagement with, or have been informed by, the October Revolution, where others for a variety of reasons chose not to, or were unable to, organise commemorative events 22. While thinking of this spectrum, it is also important to note, on the other hand, how organisations with very different political agendas from the Russian revolutionaries have tried to appropriate the story of Soviet Russia. To give one example: Anuradha Ghandy (1954-2008), former central committee member of the Communist Party of India (Maoist), wrote in 1984 of an instance when the editors of Navakal, a Marathi magazine, visited Soviet Russia and celebrated their restrictions on religious practice, arguing for why that enabled a “curbing of Islam” and may be very compatible with their version of Hinduism, seeking to create (in Ghandy’s critical reading) a “social base for Hindu chauvinistic philosophy in the country (2011, 451-455).”

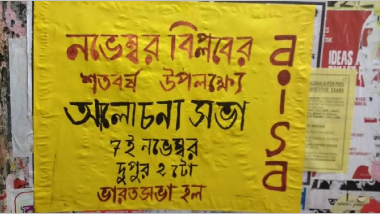

(Poster in the Kolkata Coffee House building, in College Street, for an event on November 7th, organised by the All India Students Association, student wing of the Communist Party of India – Marxist Leninist (Liberation))

For English readers curious about the broader discussions in India, in terms of research publications, worth particular mention is the Economic and Political Weekly’s Special issue, which features a number of powerful articles from different perspectives. Within the realm of English journalism, The Wire published a series of great articles. Frontline’s Special Issue, “Red October in Retrospect” has a number of strong and detailed articles (including by authors who may be familiar to a British readership, such as Tariq Ali), and the pieces discussing anticolonial movements around the world may especially be of interest. I would strongly recommend these three series, as well as those publications in general!

(Chorus performed a choreographed sequence of poetry and songs on November 7th)

(Gonobishan, a cultural organisation which reached its peak in the 1980s, performing songs on November 7th. Joly Bagchi, seated with the harmonium in the centre, has been a member of the group since its founding in 1977. While presently they focus on performing songs, in the 80s they also performed plays, as I learnt from Bagchi in 2015. She spoke of how they would perform their songs and plays at factory gates, and travelling around various districts in the state, alongside performing in halls)

Aside from other articles in some of the Bangla magazines I referenced above, there is also a lot of material available in English on other political trajectories that draw from the Russian revolution, which are not here represented by the survey of groups whose events in Kolkata I was able to attend. Reflecting in that vein on 100 years of the movement, Nandita Haksar discusses, amongst other things, the early work of the communist party in Kashmir, and the story of how Srinagar’s central square came to be named Laal Chowk, or Red Square. This year also marks the 60th anniversary of the Kagmari conference in East Pakistan (contemporary Bangladesh), organised by Maulana Bhashani (1880-1976), often known as the “Red Maulana,” about whose creative mixing of Marxism and Islamic theology I have learnt a lot from Layli Uddin’s work. Returning to the colonial contexts I began with, for those within travelling distance of London, the British Library holds copies of proscribed literature from various Indian languages including English 23, with a huge collection of communist literature that was shipped to the India Office. This includes translations of Marx and Lenin, which “began to circulate, and were inevitably proscribed’ (ibid, VIII).”

B. R. Ambedkar (1891-1956), author of the Indian constitution and a founding figure for dalit organising in India, converted to Buddhism in 1956, and wrote in the unfinished Buddha or Karl Marx: “It has been claimed that the Communist Dictatorship in Russia has wonderful achievements to its credit. There can be no denial of it. … We welcome the Russian Revolution because it aims to produce equality.” Yet, he focusses the bulk of his efforts in this text at developing a critique of the Soviet experiment. While Ambedkar’s India and Communism has been freshly published this November (and his texts have been available for free online), they have hardly been discussed in this context. At a time when India and much of the world is lurching dangerously to the right, it is very promising to see a sustained interest in the Soviet experiment. Yet, while these discussions have taken on board or advanced a variety of critical positions, there remains much to be desired in these engagements, or lack thereof, with new scholarship using Soviet archives, reckoning of the sufferings birthed by the revolution beyond a mere question of mentioning “mistakes” without much elaboration, and the creative work of those others who have constructively but critically grappled with its legacies from different political lineages.

Britain and the countries that make up the Indian subcontinent are intimately tied together by their colonial past. Yet, as I observed while reading for a BA and an MPhil in English literature in England, histories of Britain rarely locate the nation within the colonial economies that produced it, though such curricula are increasingly facing organised pressure at various universities. Even for the purpose of understanding the history of British communism, it is essential to study the former colonial domains in a more sustained manner. While the opening section of the essay addresses itself to that concern directly, in the following two sections too I have tried to gesture towards the need for addressing familiar questions through new modes of international collaboration. The legacies of the Russian revolution are being inherited, interrogated and reformulated by different and mutating political lineages in India.

-

I am very grateful to Tania Bhattacharyya, Elle O’Rourke, Tom Gann and Tanima for their feedback on earlier drafts. ↩

-

Within this article I have referred to the “October revolution,” except where quoting from or referring directly to a publication that calls it the “November revolution,” which is very often the case. For further on the politics of time and naming, see this article. ↩

-

The incident is narrated by Rathindranath Tagore, son of the Nobel Laureate Rabindranath Tagore, in On the Ages of Time (1958, 146). The Bangla translation of this was excerpted by Ashok Chattopadhyay in his article “Banglar Shomokalin Potropotrika o Buddhijibider Chokhe November Biplob [The November Revolution through the eyes of contemporary Bangla publications and intellectuals],” Aneek August-September, 2017 (32-44), from where I have translated back into English. ↩

-

“Bolshevik Bhoot o Robindranath [The Bolshevik ghost and Rabindranath],” in Aneek, November 2017, 12-16. ↩

-

Sumit Sarkar writes: “In October 1920, M.N.Roy, Abani Mukherji (another ex-terrorist convert who later quarrelled bitterly with Roy), and some muhajirs (Khilafat enthusiasts who had joined the hijrat in 1920 and crossed over through Afghanistan into Soviet territory) like Mohhamad Ali and Mohammad Shafiq founded a Communist Party of India in Tashkent, together with a political-cum-military school (1983, 247).” This founding date is also currently claimed by the Communist Party of India (Marxist), amongst others. ↩

-

The Communist Party of India recognises a different founding occasion: “On December 26, 1925, a few ardent young patriots moved by the urge to free the motherland from colonial bondage, inspired by the Great October Socialist Revolution and fired with revolutionary zeal, braved imperialist persecution and came together in the city of Kanpur, to form the Communist Party of India with a view to fight for national independence and a future of socialism.” ↩

-

The Journal of Asian Studies, Vol. 23, No. 1 (Nov., 1963), pp. 93-101. ↩

-

Sobhanlal Datta Gupta’s “The Russian Revolution, the Third International and the Colonial Question” discusses some of these contexts, and also in passing references other (non-Indian) contributions to the debate. “Mustafa Subhi (Turkey), for example, pointed out that the destiny of the European revolution was also dependent on the fate of the revolutionary movements in the East (Riddell 1987: 208–09).” Given the more familiar arguments about how the Russian revolution’s success depended on successful revolutions in Western Europe, such counterpoints may prove very helpful to think with. ↩

-

See for instance Suchetana Chattopadhyay’s An Early Communist: Muzaffar Ahmad in Calcutta 1913-1929 (2011, 131-133): “Muzaffar was particularly skeptical of Roy’s initiatives to rope in bhadrolok nationalists to the nascent communist movement (131).” ↩

-

From unpublished MPhil dissertation by the author, “Translating Gandhi: The Dandi March, the Second Round Table Conference and British Anticolonialism”, submitted to the English Department, University of Cambridge, 2012. ↩

-

See for instance the commendation of the developments in Naxalbari in “Spring Thunder Over India,” first published as an editorial in People’s Daily, organ of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China on 5 July 1967. It was reproduced in Liberation, CPI-ML’s English mouthpiece, in November 1967. ↩

-

See for instance a map published in Deshabrati, a CPI-ML mouthpiece, on April 23rd, 1970, and reproduced by Sumanta Banerjee (1980). ↩

-

The brutality of state response towards the movement has been widely documented. See for instance the Amnesty International report published in 1974, which estimated that at the point of its publication there were 15,000-20,000 “political prisoners” in West Bengal alone, most of them “Naxalite”, many of them held without trial for two to three years. It reported that as per official figures 88 Naxalites were actually killed inside prisons between December 1970 and June 1972. Various horrific torture techniques are also described in the report. ↩

-

This figure has been very widely reported, even outside India, and became for a while almost journalistic cliché while reporting on the movement. See for instance http://www.tehelka.com/how-many-deaths-before-too-many-die/?singlepage=1 ↩

-

See for instance Gautam Navlakha’s survey of reportage on this subject in 2014, or the comments of union minister of state for home, Kiren Rijiju on this subject that same year. ↩

-

I have only cursorily read these four publications as of now, and offer no comments. ↩

-

https://www.britannica.com/topic/Winners-of-the-Nobel-Prize-for-Literature-1856938 ↩

-

This is a point that Bhadra makes as well, though Shome’s article in comparison is more helpful for telling a longer story of various shifts in his positions. Aside from locating Tagore in his intellectual contexts, Shome’s narrative works its way through early correspondence by Tagore as a child, his depiction of Russia in the short story “Kabuliwala” (the story of a visiting merchant from Kabul, 1892), through the different occasions when he declined or withdrew from invitations to tour Soviet Russia, to his visit in 1930 – when he was taken aback by Soviet achievements – which seemed like “feats from the Arabian Nights” – and wrote glowingly about them, while still maintaining that there were errors in their approaches ↩

-

Some of his English work can be seen here: http://www.epw.in/author/badruddin-umar ↩

-

Aditya Nigam wrote in that article: “Writing in December 1917, Antonio Gramsci, the Italian Marxist leader, welcomed the Russian revolution as a revolution against Das Kapital. “In Russia,” he wrote, “Marx’s Capital was more a book of the bourgeoisie than of the proletariat. It stood as a critical demonstration of how events should follow a predetermined course: how in Russia a bourgeoisie had to develop, and a capitalist era had to open, with the setting-up of a Western-type civilization, before the proletariat could even think of…its own revolution.”” ↩

-

Relatedly, for curious English readers: Vijay Prashad’s article in Frontline includes a brief discussion of how “Progress Publishers became an indelible part of the postcolonial literary landscape in India.” ↩

-

The Wire, for example, published an article by Michael S. Bernstam, discussing the role played by independent India’s first Prime Minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, in the opening up of parks in Soviet Russia for free access, thereby changing the game in terms of spaces for dating. Though Nehru’s party the Indian National Congress, a party-of-order that spent November gearing up for vital state elections, had no interest in commemorating the Russian revolution, these remain important parts of our history. ↩

-

Publications Proscribed by the Government of India: A Catalogue of the collections in the India Office Library and Records and the Department of Oriental Maniscripts and Printed Books, British Library Reference Division. ed Graham Shaw and Mary Lloyd. The British Library 1985. shelfmark 2725.c.360 ↩