EDITION: 5th Birthday.

Understanding the possible trajectories of Sudan since Omar al-Bashir was deposed requires locating it within the tide of forces, local and global, that regularly bypass its nominal borders.

“O’ Mother, what’s your debt?

The debt of the nation, double.

Did you see Zayn’s child?

The only one in his mother’s eye

Filled with tears

The army said to him, ‘How many are your people?’

‘Show us where they stay’

‘Show us for your sake’

He stood like a branch, uncracked

Never broken

Never to waver

Upright towards his death

‘I won’t bring the shame’

‘I won’t bring the shame’

‘Even if they bleed me dry’”

Mahjoub Sharif, ‘O’ Mother, O’ Mariam’1

“Shoot at everything,

at every gust of wind—without warning,

at every word travelling without passport.

Train each bird to file an intelligence report.

Train all windows in cities,

all lanterns in villages,

all stems of sorghum.

Have all ants join the informants’ ranks.

Have the drizzle write intelligence reports.

Even better, pack all the people in bottles.

Keep a close watch on the starving.

Stamp the hell out of the downtrodden,

shell and bomb them down.

Confiscate the stars from the night,

the tide from the sea.

Scratch the morning face.

Cut down the wind’s wings.

Block life’s veins

and send hope to exile;

hope brought in

by the discovery of fire

and division of labour.

Perhaps

then you can get a safe haven,

Buffoon!”

Mahjoub Sharif, ‘Buffoon!‘2

Introduction: The State of the Nation

In August 2021, Muawiya al-Barir, a Sudanese businessman close to the Inghaz (The Salvation)3 regime of Omar al-Bashir that had fallen two years prior, was arrested under the guidance of the Empowerment Removal Committee (ERC), part of Sudan’s post-dictatorship transitional government.4 Typical of the ravenous neoliberal schemes nurtured by the reign of Omar al-Bashir’s National Congress Party (NCP), the Kanaf5 Abu Na’ama project – a state-owned agricultural project started up in the 1970s in Sennar State6 – was stripped apart and sold off to private investors — al-Barir included — a decade prior, disrupting the livelihoods of local farmers. Unlike the largely counter-revolutionary measures fostered by the then transitional government, the ERC was given the mandate to reverse the “unlawful” expropriations conducted by the dictatorship and to dismantle the “deep state” of Kayzan – the popular nickname given to the NCP’s brand of Islamists – that it had left behind. Despite its limitations, the exceptional character of the ERC as a factor in class struggle did not go unnoticed, as accusations of corruption, overreach, and absolutism were directed at the ERC by factions of the transitional government. In October 2021, the military wing of the transitional government (hereby referred to as the Transitional Military Council, TMC7) carried out a coup against its civilian counterpart, disbanding with it the ERC, now to be replaced by a committee with the mandate to reverse the repossessions made by the ERC. In coordination, former members of the ERC were harassed by security forces and arrested over the coming months. On April 24th, Sudan’s Supreme Court ruled to return all assets seized by the ERC from Muawiya al-Barir, now out of jail, back to him, re-privatising the Kanaf Abu Na’ama project. Less than a month later, on May 18th, popular demonstrations against this second expropriation of Kanaf Abu Na’ama were sprayed with gunfire and tear-gas deployed by the forces of the TMC, killing three civilians and severely injuring more.

The initial uprising that unseated Omar al-Bashir began in December 2018, initiated by a collapse in the Sudanese pound and the retraction of bread subsidies by the state. By April 2019, al-Bashir was deposed by his own forces, trying to satiate a wave of popular pressure. Attempts to replace him with another face from his security apparatus ended in failure, as the Sudanese resistance committees – organising protests, strikes, occupations, and sit-ins – persisted. By the end of the summer, the internal – between and among the Sudanese, protesters included – and external contradictions – between Sudan and the regional/world-systems it found itself inextricably bound by – that had plagued the early uprising would gain a dangerous institutional foothold in the form of the Sudanese Sovereignty Council, a transitional government bifurcated between unelected military and civilian parties. The Sovereignty Council’s supposed mandate was to be the oversight of the government until future democratic elections, scheduled to be held in late 2022.

The Sovereignty Council was largely embraced (though, by no means, universally) by a wide array of opponents to the erstwhile junta: civilians that had taken to the streets against the regime, facing murder, rape, and torture at the hands of a bloated military apparatus; segments of revolutionary activists, organized within the grassroots resistance committees, that held support for political networks involved in the negotiating the early transitional government; the secretive Sudanese Professionals Association (SPA), a union of mainly doctors, journalists, and lawyers, who had come to play a leadership role in the protests once held by the trade unions in earlier revolts; liberal-leaning professionals in the diaspora that had fled Sudan for wealthier Arab states or the West; technocrats across Western governmental and non-governmental organisations, who saw the moment as an opportunity to welcome Sudan into the folds – and “responsibilities” – of the “international community”; the traditional party networks of Sudan that had regularly rotated between opposition and partnership to the regime; and the regional powers that had come to clash with Omar al-Bashir or held preference for actors brought up under his tutelage. Meanwhile, the Sovereignty Council brought together a) civilian politicians and professionals with liberal sympathies chosen by the Forces of Freedom and Change (FFC), b) former “revolutionaries” from the expansive array of Sudan’s opposition militias, and c) representatives of the state’s autonomous military and paramilitary forces.8

This contradictory network, encouraged to produce a “consensus” at the expense of the spoken and unspoken interests they represented, had no real prospect of success, despite the aspirations projected onto it by a population devastated by state-sanctioned war crimes and exhausted by the seemingly unstoppable wheels of under/de-development. But worse yet, the Sovereignty Council would midwife the counter-revolution in Sudan. In its formal role, the Sovereignty Council was meant to leverage impulse to quickly institutionalise “civilian” gains with those to end the revolutionary unrest that had shook the nation over the course of the year and had been galvanised by the TMC’s June 3rd massacre (on the first day of Eid al-Fitr, no less) that had left over 100 dead. Importantly, the Sovereignty Council also seized on the political unevenness across the protests, holding a fraction of Sudan’s institutions and elites responsible for contradictions that were more central to the (re)production of the state and its successive political formations.

In the period between the establishment of the Sovereignty Council and the eventual usurpation of its civilian wing (August 2019 – October 2021), the TMC had strengthened its institutional roots, extending its direct ties with authorities in the KSA, the UAE, Russia, and Israel, expanding its capture of basic state functions (like food distribution) in key rural municipalities, and excluding itself from association with the ongoing austerity mechanisms demanded by the international community and undertaken by the civilian arm of the Sovereignty Council. Doing more than just biding time, this interim allowed the TMC the opportunity to substitute itself for the role played by Omar al-Bashir’s network in holding together the patchwork of the state and its sponsors.

In response to the coup, the foreign patrons of the military in the GCC and Israel have remained largely intransigent to criticism and “expressions of concern” from the West. Popular protests, however, have reignited, taking aim at both the new military junta and the possible restoration of the former regime. Perhaps the most vital slogan to this new round of protests is the declaration that “Retreat is Impossible,”9 signalling – at least for the time being – a widely-shared rejection of normalisation with the military dictatorship, including in the return of the shared military-civilian transitional government.

At the same time, the technocratic strategy has been the retreat to “normalcy,” a return to the “transitional” military-civilian power-sharing compact. As the ongoing coup is nearing its anniversary, the allure of co-governance – “power” constrained by power – has become intoxicating for Sudan’s political class and its established opposition parties.

The burgeoning desire for an “easy victory” was no better reflected than in the antics of Abdalla Hamdook, once the highest-ranking civilian figure – the Prime Minister – of the Sovereignty Council. Initially pursued by the coup plotters, Hamdook was held under house arrest for a month until release, a situation “resolved” by his announcement of a political settlement that would reinstate himself (and not the rest of the civilian forces of the Sovereignty Council) as prime minister of the new military government. Unsurprisingly, this reinstatement was short-lived, with Hamdook again exiting the partnership just past the new year, his reputation in tatters among the ongoing protest crowds as a result of his “antics.” Sadly, Hamdook’s failure didn’t lead to the discrediting of the obsessive compulsions of Sudan’s venal and naïve technocratic class, but rather its galvanisation. Taking office in January, the United Nations’ Special Envoy to Sudan, Volcker Perthes echoed the belief that the only acceptable settlement for Sudan lies through restoring its divided house. So thorough was his commitment that, at the end of May 2022, he took his opportunity to declare his contempt for the “spoilers” – meaning protesters who rejected normalisation with the junta – who were to be held responsible for the failure of any democratic outcome, a view shared by the “international order.”

While demonstrations against the junta have proceeded unabated, Perthes’ words have since resonated with the welcoming approval of none other than the military junta itself. Talking to the cameras in early July, the face of Sudan’s military coup, Abdelfatteh al-Burhan, announced that the military would step back from negotiations, welcome a government led by the same civilian technocrats it had initially deposed, and maintain autonomous and “neutral” oversight of security and defence in the guise of the High Council of the Armed Forces. While this strategy was in no small part driven by the ongoing failure of the junta to establish rule and stability the “moral and intellectual” authority in the face of the resistance committees, its main aims were to enshrine the absoluteness of military authority over “military matters,” a classic trope of the 3rd World security state, and to voice a call of return for Sudan’s political elite. And no sooner was the call returned, with the Democratic Unionist Party and the National Umma Party, the long-standing political wings of Sudan’s most influential Sufi orders, welcoming the news as a magnanimous invitation to the Sudanese people. Armed opposition forces have expressed some reservations, but have entertained the notion, revealing the tenuous links that exist between militancy and principle. And while the resistance committees widely rejected the facade put-on by the junta, some among the opposition forces, including factions of the ever mercurial FFC, seem enticed by the prospect of resolving a crisis by pretending it never existed.

The vast majority of this piece was written in December 2021 and January 2022. While they deserve a fuller treatment, this introduction, written in summer 2022, aims to fill in some of the developments of 2022, particularly the evolving forces of revolution and counter-revolution.

The coup has entered a steady phase of repression. In towns and cities, this is most often characterised by the confrontation between protesters and various military forces, armed with guns, drones, and Humvees and supplemented by plain-clothes informants scattered across the crowd. In regions of Darfur, however, where a militia like the Janjaweed – now rebranded as the Rapid Support Forces, or RSF – famously “cut its teeth” in the practice of counter-insurgency, we’ve seen the return of stochastic massacres, internal cleansing, and a wider array of war crimes committed at the behest of the RSF, driven in part by ongoing disputes surrounding resources in symbiosis with a discourse of racial supremacy.

These massacres also pose as potential fractures for the ruling military alliance, which has managed to integrate the armed forces from both former rebel movements – particularly in the states of Darfur, Blue Nile, and South Kordofan – and those backed by the state. A figure like Jibril Ibrahim, current Finance Minister and a leader of the Darfuri Justice and Equality Movement (JEM), has stayed on-board with the coup government. Similarly, the Sudan Liberation Movement (SLM), another rebel militia based in Darfur, has been party to the same coup, under the guidance of Sovereignty Council member and SLM leader Minni Minawi. These accommodations between previously warring factions have been eased by an implicit stakeholder process that has entrenched militia – rather than federal – authority across the countryside.10 But the scale of the atrocities again at work in Darfur, alongside disputes over power-sharing arrangements and the distribution of the wealth accrued from the militia-run gold industry, may become genuine barriers for any smooth reproduction of the current military coalition.

These contradictions even reach into the opposition forces, most notably for the Sudanese Communist Party. While the party’s historic reputation looms large in the intellectual and cultural milieu of Sudan’s activist, labour, and nationalist movements, it currently exists as a shell of its former glory, brought about by decades of repressions and reflected in its proclivity for conciliatory engagements with contradictory and ill-fated coalitions.11 As a member of the Sudan Revolutionary Front (SRF), the Communist Party remains member to a coalition that includes the Ibrahim’s JEM and the Minawi’s SLM, a complicity with the putschist forces that it has tried to explain away by holding out for the prospect of internal struggle within the front.

Meanwhile, far from Sudan’s shores along the Red Sea, the Russian invasion of Ukraine has dramatically unsettled both core and periphery in the world-system. Besides the ridiculous visit of one of Sudan’s most notorious war criminals to express solidarity with Russia’s supposed “operation against Nazism,” the collapse of both Russian and Ukrainian grain exports has amplified the pre-existing food crisis in Sudan, similarly rocking Lebanon and Egypt. Given the role hunger played in the intifada that unseated Omar al-Bashir and the current talk of food export bans being enacted, the military junta will find it that much harder to enact anything like a stable hegemony that it and its civilian negotiating partners so desire. Instead, it will likely to choose to respond – as it has up to now – by greater force.

Meanwhile, the American imperial project – and the world-trotting Northern Atlantic Treaty Organization – has been morally revitalized by the invasion at a moment when the War on Terror had become increasingly discredited12 in the eyes of a number of core states. No serious signs suggest that this’ll mark a turning point for Sudan’s relationship to the current hegemon, but the potential political or military interventions it commits to elsewhere may produce dramatic ripples across the country. Similarly, European and American demand for oil has provided new leverage for the KSA and UAE. Previously unsettled that Washington would prove a mercurial patron, they’ve both looked to remain impartial in the midst of the conflict with Russia, even attempting to slowly amend their fractures with the Turkish and Syrian regimes. More worrying for Washington, this growing distance between the United States and its Gulf collaborators has frustrated American calls to increase the rate of oil production by OPEC states. One potential resolution might currently be in preparation by the White House administration, in the form of a discreet visit of American officials to the KSA. As explored in the piece, the KSA and UAE’s relationship with the forces that comprise the TMC has been a vital component of the TMC’s ascension to power and the restored pre-eminence of the Gulf powers may bolster their commitment to establishing regional hegemony, ranging from political intervention in Tunisia to the military devastation of Yemen.

Nevertheless, while these developments have either been excluded or only partially captured in the following essay, Sudan’s impasse remains defined by a number of broader themes found across the world periphery: brief uprisings followed by a prolonged period of counter-revolution; the return of the ancien regime or its farcical re-enactment in its stead; dictatorships that rule by raw military power, lacking even the traditional mantras surrounding “development and growth”; popular (and often urban-driven) non-violent mobilizations that emerge in the context of protracted armed conflicts across the rural peripheries; the (gradual) ossification of traditional political vehicles; sharp geographic divides defining state control and development, channelled through a complex of religious-racial-tribal signifiers; multi-gendered struggles that reproduce the existing division of labor; the subsumption of the 3rd World state and its vestigial institutions to the diktats of a global border regime; the collapse of traditional working-class occupations and the emergence of a sizable strata of de-classed, college-educated youth; the contradictory roles of the so-called “lumpenproletariat,” agents of both revolution and counter-revolution; the persistence of the agrarian question, woven into a crisis surrounding food sovereignty and security; and the local balance-of-forces being shaped, in subtle or profound ways, by the crises of regional and global hegemony.

How the Sudanese impasse will resolve itself is anyone’s guess, but to identify both opportunities and challenges requires locating Sudan’s trajectory within the tide of forces – local and global – that regularly bypass its nominal borders. While most descriptions of the uprising(s) in Sudan have provided strong and powerful activist accounts – ones that provide direct insight into what will ultimately be the most important force in shaping Sudan’s fate – this essay will try to provide complementary account of certain historical and geopolitical developments that have shaped the terrain of the current struggle, including: the fiscal collapse of the territorial state; the rise of the post-colonial military state; the power struggles of the Persian Gulf; the paradigm of Fortress Europa; and the question of the urban-rural divide. It is this set of constitutive factors in the courte durée, where cattle-herders meet the hard currency demands of the United Arab Emirates, that we turn our attention to.

2011, a Pre-History:

Over the course of Sudan’s post-Mahdist history, the late 19th century millenarian project that conceived the modern foundations of Sudanese national identity, authority has largely been held in-and-across two camps: the riverine landed tribes of the North and the Sufist brotherhoods, distinct camps whose fate – especially through its elites – would remain intertwined.13

The early precursor to Omar al-Bashir’s political network was borne out of the 1940s Sudanese encounter with the Muslim Brotherhood, when students flocked to Egypt for schooling. The Brotherhood’s social prowess, however, would not emerge until it found its guidance under the wing of Hassan al-Turabi in the 1960s. Motivated by what they perceived as an incomplete “decolonisation,” of Sudan14 this network grew in the opposition to the increasingly erratic reign of Jaafar al-Nimeiri, a president whose dictatorial reign from 1969 until 1985 found him switching allegiances from the “patriotic” military socialism of the late 1960s (a la Nasser) to pan-Arabism (a la early Gaddafi) to the Islamist politics that would ultimately come to succeed his reign. Al-Turabi, active in the Libyan-based15 armed opposition among the Northern political establishment during the 1970s, would be well-poised to leverage Nimeiri’s faltering hold on power through his new strategy of strategic co-optation. Acting as a figure of “national reconciliation,” al-Turabi was able to grow his network of activists – the tanzim (organisation) – while encouraging the ever-chameleonic Nimeiri’s final political strategy of moral restoration and religious law.

The religious, however, was also the geographic – speaking to widespread dissatisfaction in the South stemming from the moment of independence, the turn to Islamism signalled a new iteration of Sudan’s racial-religious-colonial complex of political marginalisation, economic underdevelopment, and recursive coloniality that had triggered the first Anyanya separatist movement decades prior.16 Nimeiri’s strategy for survival had sparked the Second Sudanese Civil War, a conflict that saw the introduction of the Sudanese People’s Liberation Movement (SPLM) and its charismatic leader, John Garang. Unlike the Anyanya revolt, however, the nominal political call of the SPLM was not for independence, but for the establishment of a “New Sudan,” free from the political, geographic, ethic, and religious boundaries that had been endemic to the post-colonial state.18 The SPLM, unlike the secessionist Anyanya movement, would in-turn gain support in pockets of Sudan’s Islamic peripheries – namely the Nuba Mountains and in Blue Nile state.19 Over the course of the civil war and Nimeiri’s brutal pacification campaign in the South, political resistance to his regime grew as state capacity was directed to serving the war effort, leading to the 1985 April Intifada and the fall of Nimeiri.

Meanwhile, the network that al-Turabi had founded hit its territorial limits, particularly along the religious boundaries that had come to demarcate the future South Sudan. But it had also made extensive in-roads across the Muslim peripheries, particularly in Darfur. If the post-colonial state had offered little reprieve from the inegalitarian domination of the political center of Khartoum, for many Darfurian activists (particularly among the educated), a new Islamist politics, separate from the historic Sufi brokerage networks, could potentially serve as a new foundation for an equitable state identity. On the other hand, both the popular classes and the elite beacons of Darfurian “customary authority” were often integrated into the pre-existing Sufist political networks of the Umma Party.20 This was reflective of a larger crisis: the difficulty of constructing a national identity and political authority that (nominally) was opposed to the traditional political order.

All this shaped the playing field of the military coup to come. A steady electoral path to power in Sudan was unlikely when the perceived political threat to the Brotherhood activists was the enshrined party establishment, the political wings of the Sudanese Sufi brotherhoods. In 1989, under the coup of the military leader Omar al-Bashir, with the secret blessing of Hassan al-Turabi, the Inghaz was born.

The Bashir-Turabi Split

In the years to follow, the Inghaz would cohere around the National Congress Party (NCP), but what would emerge from this wasn’t simply the fruition of al-Turabi’s Tanzim. While the Tanzim had initially vied to produce a new cross-national alliance that would traverse the ethnic and geographic boundaries of the Muslim North, the realities of rule had quickly dimmed those ambitions.

For one, the danger of introducing a new ideological framework is that its material content, the rituals and practices and orientations bound up with it, are open to contestation. Hassan al-Turabi quickly found himself losing grasp over the political vehicle he once dominated.21 An “unauthorised” assassination attempt against Hosni Mubarak, then dictator of Egypt, emerged from al-Bashir’s security apparatus, without al-Turabi’s knowledge. The situation for Egypt, both a crucial outpost of American imperial authority following Anwar Sadat’s normalisation and a core opponent of the Muslim Brotherhood, was unacceptable. Meanwhile, al-Turabi’s vision of internationalism, a vision that helped meld Sudan’s contact with not only the marginalised Brotherhood of Egypt, but with the Islamic revolutionaries of Iran, Afghanistan, Lebanon, and elsewhere, had garnered the scrutiny of the United States, who, like their Gulf allies, would come to make their own distinctions between acceptable (a la Indonesia or 1980s Afghanistan) and unacceptable (a la Iran and 2000s Afghanistan) Islamists. In a turn towards the domestic, al-Turabi tried to push through the “rationalization” of the Islamist political bureaucracy: the separation of the executive office from the military, the expansion of its civil institutions, and the push for a non-military – albeit Islamic – rule.22

It often happens that at core historical junctures, a coherent political vehicle comes undone as its factions move increasingly out of phase with one another: in the short term, al-Turabi’s goal for the NCP was to bring about the production of a new social subject through the motor of a pan-Islamic civil society; in the longer term, however, Sudan’s successive regimes had overseen the growth and bloat of not only a formal military apparatus, but the parasitic militarisation of all pre-existing institutions.

This wasn’t simply a story of an increasing depot of arms. The dying days of colonialism had seen the emergence of a surveillance bureaucracy (the NISS) that would come to expand to a critical mass, as it came to accommodate new functions, new targets, and new elites in the post-colonial era. Meanwhile, Sudan’s bourgeois elites did not wield an impressive industrial or commercial base to assert their influence23: systemic transformations could only be incurred through the “redemptive” coup, with the military in turn growingly cognizant of its central political role as the power-broker of the state. And in parallel, not only had the state moved in the direction of militarisation, but so had the political opposition, especially at the national peripheries. While the opposition had militarised in a largely reactive fashion, driven into warfare through the dictates of the post-colonial state, it had come to growingly occupy peri-state functions, where federal authority meant little more than the occasional massacre. If anything, this process would only accelerate during the years to come, as the state perfected its strategy of transforming (and therefore exacerbating) economic and tribal disputes at its peripheries into Manichaean military struggles.

Put simply, the NCP was not a civil society vehicle that would “peacefully” midwife Islamic “Salvation,” nor was it simply an administrative tool shed of the bourgeoisie: it was a weak bureaucratic-military complex, whose own internal calculus would grow in favour of the desperate martial order. Hassan al-Turabi, increasingly incompatible with the NCP, was to be softly purged by its ranks, driving forth much grander and punitive reprisals against those outside of the seats of power. al-Bashir would turn to the traditional ethno-geographic stalwarts of power, while al-Turabi would attempt to root himself in the peripheral social bases of the Islamist movement, in a fashion that would come to re-articulate an ethnicised political order:

[T]he patterns of behavior followed a clear political logic. Both Bashir and Turabi were seeking to maximize their power and needed allies they could trust to achieve their goals […] Moreover, as Turabi realized the extent of the resistance coming from Bashir and other Islamists who favored retaining a highly centralized system, Turabi seemed to have made a crude political calculation that his best hope in displacing Bashir and his allies was to tap into historical grievances among those from Sudan’s periphery who had been disadvantaged by such a system. Of course, Turabi’s supporters did not only come from Darfur and western Sudan, but many did. Thus, the geographical roots of political preferences in Sudan (with those from the Nile River Valley favoring a strong centralized government and those from the periphery favoring stronger state governments) go a long way toward accounting for the regional nature of the Turabi and Bashir split. A final key factor that may account for Bashir’s decision to fall back on riverain Arabs, especially those from his own tribe, the Ja’aliyin, was the informational advantage that comes from shared ethnicity […] Even though both Turabi and Bashir pursued such ties for political, geographic, and informational reasons and not for ethnic reasons per se, to the other side it also looked like and could be ethnic mobilisation.24

How Far Does the Territorial State Go?

The absolutist state has never been a reality for any of Sudan’s successive regimes – from the Turkiyya to the British colonial era to the array of faces that were elected to (and more regularly captured) executive authority. The stratagem of Omar al-Bashir, however, was not to quixotically discover the “holy grail” where others hadn’t; it was to forge it out of necessity. This forgery was like a replica of what was happening across the global supply chain: political patchworks and fiefdoms coming to govern over a decentralised economic unity that traversed sovereigns and nations. Darfur was in the midst of a new wave of violence, driven by levels of economic deterioration, land disputes, and politicisation by way of ethnicisation.25 Frustration was at an all-time high in Darfur, with anti-state rebels organizing under the non-Islamist Sudan Liberation Army (SLA) and the “Turabist” Justice and Equality Movement (JEM). Meanwhile, the central government was looking to demobilise its southern theatre through diplomatic negotiations with the SPLM. The NCP made the pacification of Darfur a priority.

Circumstances were not the same as they were when the Inghaz took power. While the NCP was once able to rely on its networks to broker a “cooperative counterinsurgency,” now it had no clear option. Instead, it chose to take it’s campaign of repression to the sky, deploying a devastating aerial bombing campaign, as well as resorting to a strategy of decentralized counter-insurgency, delegating much of its frontline operation to a new militia, the Janjaweed. The Janjaweed’s emergence had been, like the anti-state rebel movements, shaped by the enduring proxy wars across the Libyan-Chadian border.

Idriss Déby, Chad’s former leader who died this past year, had been an important power-broker in Western Sudan across multiple decades. As he fought for state power, his military gains, funded and armed in part by Omar al-Bashir, against former Chadian president Habré in the early 1990s had also signalled declining support for the first wave of the Darfuri rebellion, inadvertently encouraging the later integration between the Darfuri rebels and the SPLM of the South.26 A decade later, Omar al-Bashir would rely on Déby, a Zaghawa, to utilise his “ethno-racial” solidarity to stymy the new wave of Darfuri rebels. But despite Déby’s eye towards maintaining friendship with Khartoum (an “eye” strengthened by growing direct animosity between the rebels and Déby), his military apparatus was largely a great deal more sympathetic to the Darfurian cause. Reality did not live up to al-Bashir’s hopes for a successful strategic pacification by the Chadian state, and, in turn, he buttressed his counter-insurgency by turning to Abbala Arab pastoralists, living across both Sudan and Chad.27 Many of these pastoralists, who would serve as the initial core of the Janjaweed, had been shaped by the experience of prior militarization, working as a proxy militia for Gaddafi against the Chadian state during the 1980s, mirroring the militarised mobilisation of the Zaghawa undertaken by Habré. Furthermore, the Abbala pastoralists had already been at odds with the landed communities of Darfur over the use of land and resources, with the former hoping that an alliance with the state would serve as a shortcut to political domination in the region. The result was catastrophic.

As a result, the casualty count of the government’s counterinsurgency skyrocketed. Omar al-Bashir had confronted and “overcome” the decline of an older set of counter-insurgent tactics, increasingly understood on the part of pro-government forces through the framework of “racial war.” His path to victory was built through a mountain of corpses. His strategy had entailed a new double movement: rule of a centralised military authority established through a growing web of decentralised warfare.

The Janjaweed, later rebranded as the tame Rapid Support Forces (RSF), took advantage of these changing circumstances. Omar al-Bashir’s NCP had slowly contracted into its military core, shedding off its activist and – later – business linkages. But in Sudan’s peripheries, it was the militias that were now expanding, acting as the core of new para-state formations. It reflected something like, to adopt Sudanese analyst Magdi El Gizouli’s coinage, the subsumption of the state to a “militia form”:

[I]n Sudan’s vast peripheries the RSF, thanks to its military organisation, logistical capabilities and command over surplus, has assumed social provision and insurance functions. RSF units dig wells, organise health care, deliver vaccines and supervise rural extension and the development of entrepreneurship skills a la International Monetary Fund and World Bank recipes.

But while the RSF was uniquely poised to take advantage of its state-backed sponsorship, a wider process of deformation — where large swathes of Sudan’s rural peripheries found themselves subsumed to the dictates of the largest gun wielder, gathered apace. This was even reflected in the governance of rebel groups at odds with the state.

In the coming years to 2011, the NCP had finally “resolved” the “Southern Question” that had plagued successive administrations. Following John Garang’s death and the Comprehensive Peace Agreement of 2005, a referendum on independence was finally on the table in 2011. The overwhelming majority of Southerners chose secession. This decision came with much celebration in the South, a sense of nostalgic loss for liberals of the North, frustration for the allied rebel movements of the SPLM across the North, and cautious optimism from the NCP. The South posed a unique threat for the project of Islamism: its Muslim population was exceedingly marginal and half a century of warfare had done nothing to change those circumstances. Secession, however, also led to the direct loss of the NCP’s oil supply: South Sudan “resided” on the territorial resource base of the state’s crucial exports, a situation for which there were no easy substitutes in the North. The NCP would attempt to salvage the situation through leveraging their infrastructure, including the only oil pipeline leading out of South Sudan and into the Eastern city of Port Sudan. But production and transport were frequently irregular, disappointing the NCP. South Sudan would regularly come to head with Sudan over the oil industry, the share of its proceeds, and the “internal security” issues of the North, where the ongoing conflict of erstwhile enemies and allies threatened to spillover into Southern borders. Most importantly, South Sudan would take a turn towards civil war, as the power asymmetries of the SPLM helped mobilise ethnicised warfare.

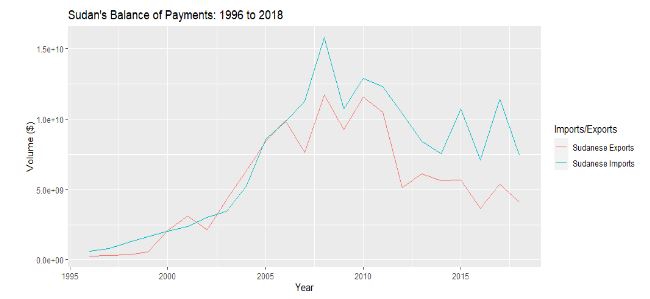

The NCP’s survival strategy had “saved” Sudan through imposing two hard boundaries on it. The choice to outsource and integrate warfare at the rural margins, most notably in the case of the Janjaweed in Darfur, would transform the power distribution in Omar al-Bashir’s military state apparatus. As the geopolitical space al-Bashir relied on rapidly shifted, it was perhaps the peripheries of this network that would have the most to gain. A trajectory of economic decline was almost guaranteed. Sudan’s balance-of-payments would enter free fall. Exports declined, taking with it the fiscal capacity necessary for imports. As a consequence of declining GDP rather than increasing inflows, remittances would begin to steadily mushroom as a percent of GDP from 2015 onwards, growing from 0.29% to 2.32% by 2020, steadily moving closer to the highs that were characteristic of the 1990s and 2000s, where remittances had reached nearly 11%. These changes become even clearer when we look at how these remittances were used to service imports: by 2018, Sudan’s remittances constituted about 40% of total imports, while covering more than 70% of its trade deficit in the same year.28 The collapse of Sudan’s primary source of revenue meant that the state would come to rely heavily on short-lived extractive projects, patron-clientele sponsorship, and capital-accumulating schemas that would enrich increasingly small slivers of the Sudanese population, including its elite, while impoverishing its total capital.

New Tides in the “Old World”:

In the years following the Arab Spring, the undercurrents that ran through the Persian Gulf now produced tectonic shifts. Unexpectedly, Iran had grown to be a powerful military authority, moving beyond the weak internationalist Islamic activism of its early years to forging a complex and far-reaching network of armed regional allies. These alliances were in some ways unexpected (save for Hezbollah in Lebanon, neither the Syrian state nor the Yemeni Houthis were parcels of the same ideological movement that had produced the Islamic Revolution) and grew less from natural affinity than from the gravitational force of a shared constellation of opponents (the United States, Israel, and Saudi Arabia). This growing field of actors – nicknamed “The Resistance” by its supporters – had largely coincided with Iran’s growing domestic military capacity, driven perhaps most directly by its missile technology. And while Iranian military power couldn’t translate to economic prowess, both the scale of its largely educated yet underemployed workforce and its resource-rich territorial base could theoretically pose a looming challenge for the established petro-authority of the region, Saudi Arabia. This, alongside a growing overture towards normalisation – represented in the EU by the political leadership of Germany and Obama’s late-era “Iran Deal” – with key Western markets, ran the risk of reconfiguring the status quo in the region.

But all was not settled. For one, the dethawing of the Western relationship was an uneasy (and undetermined) contradiction played out between competing tendencies of the US’ hegemonic reign. Obama, alongside allies in the European Union, understood that economic sanctions had left Iran a hardened “pariah state,” in consequence bolstering opposition towards the United States among both its domestic political classes and, importantly, its regional allies. They found a friend in the wake of the Iranian Green Movement – a wave of liberal politicians that sought to meld some combination of geopolitical retraction, market integration, and relaxed domestic orthodoxy, reflected most coherently in the reign of then Iranian president, Hassan Rouhani. In addition, while Obama’s array of internal advisers were split, Obama had also come to express a belief that the Arab Gulf states would need to “share the neighbourhood” in coming years. This belief remained underdeveloped and half-hearted – the prior and ensuing years would see the enduring coordination between the US and its sub-imperial allies – but, given the effort put behind initially “securing” the Iran deal, it wasn’t non-existent. Trying to expand its alliances in the region also came at an opportune moment, as Obama had, at least for a time, unleashed a massive boom in the domestic shale gas industry, placing the United States as a competitor in the export market. Becoming a fossil fuel giant eased the administration’s potential vulnerability to international shocks, as it came to preside over dwindling imports of crude oil and petroleum. All-in-all, the moment was “opportune” for a transformation in US-Iran relations.29

However, this rapprochement , the pursuit of global economic integration that would inch towards superseding existing barriers to capital, ran counter to the parallel mainstay of the post-Cold War executive office: neo-conservatism. If one saw Iran as a potential trade partner, one whose “revolutionary fervour” would be constrained by joining the international community of capital, then the other saw a political model of rule that ran counter to America’s image. If the Cold War had largely accomplished its economic goals, discrediting both communism and forms of autarkic socialism as a model of development, it had nonetheless left a diverse array of state forms. This “vibrant” tapestry had been, in some ways, an outcome of the realpolitik of the Cold War: neither Deng Xiaoping nor Saddam Hussein could be said to emulate the American model of rule, but they had become crucial allies in the Cold War, regardless of their political proclivities. Even Omar al-Bashir, no classic ally of the West, was an active participant in the economic dimensions of this wider coalition.30 But total hegemony represents a double-sided coin: not only the construction of an unitary economic project, but hegemonic “veto power” over all political arrangements. With the USSR gone and the economic victor clear, the United States could go through the project of cleaning up the “vestiges” that it had been “forced” to tolerate.31 Rather than simply the “blood-for-oil” formula that had dominated popular critical analysis in the lead-up to the onslaught unleashed against Iraqis,32 hegemonic logic was operating on a different basis:

One might ask why the United States targeted the Hussein regime if it was not an imminent threat in military terms. Iraq has the world’s second-largest proven stocks of oil, after Saudi Arabia. But oil cannot provide the full explanation, or even the bulk of it [emphasis my own]. Iraq’s real significance is political. Just as after 1991 Iraq was turned into an example of the punishment that can be meted to a regime that dares go outside the framework of a U.S.-defined alliance, so the significance of Iraq after 9/11 again extends beyond the country itself. In attacking Iraq, the Bush administration hoped to achieved more than just a regime change: Iraq presented another chance to redraw the political map of the entire region, something the United States has tried several times before—the highlights being the Israeli invasion of Lebanon, which failed to create a buffer Christian state; the alliance with Iraq against Iran in the 1980s; and the war in Afghanistan […] Writing in April 2003 under the auspices of the Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs, Israeli major-general Ya’akov Amidror put it bluntly: “Iraq is not the ultimate goal. The ultimate goal is the Middle East, the Arab World and the Muslim World. Iraq will be the first step in this direction; winning the war against terrorism means structurally changing the entire area.33

This tension was shared by two of the core entities that comprised the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC): Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. While constant US allies, their politics were rarely a simple direct refraction of US authority, but rather spoke to convergent goals between state elites.34 From this vantage point, Obama’s presidency was incoherent, attempting to reconcile a push for Iranian integration with the military onslaught driving Yemen to state collapse. For Saudi Arabia (as well as allies in Israel), the former was – at the time – absolutely unacceptable. Iran represented the threat of a political model (with its own Islamic alliances) and an economic challenger (with oil tankers at the ready for export). Mohamed bin Salman would find a kindred spirit in Obama’s successor, who would tear up the Iran Deal. In sync with the spirit of Washington, Saudi Arabia would also expel Qatar from the GCC. The logic was two-fold. On one hand, Qatar had been amenable to deeper diplomatic and economic ties between the Iranian government and itself, despite its role in an increasingly sectarian landscape. On the other, Qatar had (alongside Turkey and, in critical fashion, Iran) been a crucial patron of the Muslim Brotherhood, much to the consternation of both the Wahhabist ideologues in the Gulf and al-Sisi’s military junta in Egypt.

The message was clear: Iran’s ascension would not be embraced by Saudi Arabia and, importantly for actors outside the direct battlelines flaring across the Middle East but in the Gulf’s geopolitical “sphere of influence,” normalisation with Iran was unacceptable. In the case of Sudan, Iran had once been a staunch supporter of Omar al-Bashir, even during the peak of state-sponsored war crimes in Darfur. These ties had faced their own contradictions, as Iranian military capacity had exhausted its economic strength during the course of the Syrian intervention. But for al-Bashir, Iran had meant a steady diplomatic, ideological, and economic ally. During the course of his reign, al-Bashir had maintained his survival by acting as a professional chameleon, attempting to extend his alliances as widely as possible, while avoiding the contradictions that erupted between them. But this time was different. Even preceding the expulsion of Qatar, Sudan expelled Iranian diplomats in 2014, attempting to carry sway with Saudi patrons. While the expulsions were justified under the rhetoric of sectarianism – Iran was a sponsor of Shi’a intrusion in a Sunni land, they came at a moment in which Sudan began to face an unprecedented economic decline following the collapse of its balance-of-payments after the 2011 secession.

The growing reliance on Sudan on the Gulf states would enable Omar al-Bashir to extend his reign, but it would also plant the seeds that would begin to unravel his military coalition.

Goodbye, Hello, Goodbye Gaddafi

Meanwhile, the War on Terror had not left Sudan’s neighbors untouched, perhaps no more-so than Libya. Muammar Gaddafi had come to power after a coup in 1969, at first following a model of rule inspired by Nasser’s “patriotic military socialism.” But unlike Nasser, his reign would endure through decades, owing to his ability to both integrate Libya into the power politics of the continent and avoid the hottest flashes of the Cold War. While the official Western stance on Gaddafi was initially cold, driven both by ties with the former monarchy and Gaddafi’s program of nationalisation, neither was it non-existent. However, in Libya’s role as an “internationalist” patron, direct American ties would largely collapse. It wasn’t until the end of the century that reproachment would begin.

It first came with the gradual winding down of Gaddafi’s international sponsorships, telling TIME magazine that “I supported all liberation movements fighting imperialism, but I believe that is over now.”. But beyond mere rhetoric, amelioration would emerge in the context of his turn towards securitisation. The War on Terror presented a new paradigm of cross-national coordination, centered around the threat of “Radical Islam.” In return for dismantling his nuclear armament program, Gaddafi became an ally to MI6, as Tony Blair drove the UK enthusiastically into Iraq. This warmth began to reach across the Atlantic, with Gaddafi winning the praise of the “maverick” Senator John McCain, who promised enhanced military sales.

Yet the War on Terror represented only a slight thaw in Libya’s standing: a global security campaign required far-reaching alliances, particularly with states that were either seeking to gain or maintain favour with the United States. It wasn’t British advances that dictated Libya’s trajectory, but rather that of Italy’s. In a precursor to the decade(s) to follow, Berlusconi led the European crusade against migration, even preceding the years of the Syrian Civil War. In a manoeuvre that would come to reflect the offshore detention centres undertaken by Australia in Papua New Guinea and the United States across Latin America, Berlusconi had elected Gaddafi to stymie the flow of African migrants to the boundaries of Fortress Europa. Signing a friendship treaty in 2008, Libya was compensated for its “border governance”: this meant maintaining a force of armed border patrols, overseeing detention centres, and accepting refugees deported by Italy. And, in his own words, Gaddafi could be viewed as the existential bulwark that prevented Europe from becoming “another Africa,”36 as European far-right ideologues propagandised about a nightmarish possible future where Europe was sunk by an “infestation” coming from the 3rd World.37

This set of circumstances was not to last: like the ascension of Hassan al-Turabi’s activist apparatus, Gaddafi’s moment in the European sun came shortly before the collapse of the historical wave that brought it forth. When the Arab Spring had come to Libya, Gaddafi’s fate was unclear even to his eventual executors: Tony Blair had cautioned him to flee, sparing his own life, while Obama was initially unconvinced on the course of NATO military action. Both his Defense Secretary and his national security advisor opposed taking military action (though to no strict exclusion of other tactics), while Hillary Clinton and Samantha Power championed Libya’s detonation, representing the call for extending the “Pax Americana” to the region: Obama ultimately came down to side with the latter. At the U.N. Security Council, the US chose to strike, with no dissent among the veto-holding permanent members.38 The tug-of-war between the ascendant “War on Migration,” which beckoned the Western establishment (in particular Europe) to use any “precaution” necessary to block the flow of migrants and refugees, and the older neo-conservative call to finally “democratise” a decades-old Cold War holdout had been called in favour of the latter.

The fall of Gaddafi was met with one-note celebration across Khartoum’s political circles. However, the relationship with the late colonel was rarely so unambiguous for both rebels and the state, with Gaddafi, an important power-broker and frequent meddler in Sudan, shifting regularly from friend to foe. He had, under Nimeiri, aided in capturing the political leadership of the Sudanese Communist Party following the 1971 coup attempt against Nimeiri (culminating in the execution of who can be best described as the “patron saint” of Sudanese communism, Abd al-Khaliq Mahjub), but he had also backed and armed Turabi and the traditional political opposition against the sitting leader just half a decade later. Some years later, he had also stood as a powerful ally to the SPLM. His role in Darfur was not to be understated: new political factions and broad militarisation had occurred in Darfur under the backdrop of proxy wars across both sides of the Chadian-Libyan border. Following the expulsion of Khalil Ibrahim, the former founder of the JEM, from Chad in 2006, Gaddafi provided what competing commentators have either described as safe haven or house arrest for the Darfuri rebel leader. At nearly the same time, this mercurial relationship would be concretized in Sudan’s “Corinthia,” a towering luxury hotel in Khartoum “gifted” from the late colonel in 2006 meant to signal Sudan’s developmental “advancement” into the new century, but which would instead remain largely empty and inaccessible to all but the wealthiest elites and expats. For the Janjaweed and the security apparatus, Gaddafi’s death would signal one last “gift” in the subsequent years.

The collapse of Libya was met with either silence or, in some circles of the imperial helm, a growing frustration towards what was euphemistically referred to as an “activist foreign policy.” In the years to follow, European actors would try their best to “seal” the Libyan pipeline, criminalising migrant transport, extending the militarisation of border policing, and backing warlords that promised to bring order back to the Mediterranean.39 Militarism had no end in sight, but Libya would mark something like a “signal crisis”40: the imperial “adventurism” of the War on Terror had come to a set of limits, demonstrating a singular capacity towards destruction (communicated through the seemingly banal of the “failure of nation-building”), suggesting an overextended American military enterprise, encouraging the push for a new (and, although not exclusively, most often right-wing) project of the “reclamation of sovereignty” across Europe, and transforming the internal political calculus of African states (and, in parallel, Latin American) that could deploy their “comparative advantage” in the border provisioning sector. And the RSF, alongside the security services, could provide.

¿Dónde Están?

Back in Western Asia, a greater re-alignment was emerging in the century-long war against the Palestinians. Given both the scale of the refugee crisis unleashed by the 1948 Nakba (literally, “Catastrophe”), where three-quarters of the Palestinian population were made stateless overnight by the cleansing campaigns of the Haganah, the Irgun, and the Stern Gang, and popular support for the Palestinian cause in the region,41 “Arab states” felt the pressure to maintain rhetorical support for the Palestinian camp, despite an extensive history of backroom deals and security coordination with the Israeli regime. But this era was now coming to an end.

For one, the Israelis were more than amenable to normalisation with these regional governments. Following the amelioration of ties with Egypt during Sadat’s reign, it had been clear that many states were willing to forego their anti-normalisation policies, insofar as Israel could offer an attractive deal (in the case of Egypt, it was the return of the Sinai Peninsula, conquered in the course of the 1967 War). These in-roads, however, had been partial, like South Africa’s own towards other African states during the era of apartheid (and like the case of South Africa’s relationship with Zaire and Uganda, relationships were typically kept discreet). The growth of the “Iranian crisis,” however, which saw a once-former ally of Israel (both during the Shah and, discreetly, during the Iran-Contra operations) reposition itself as a patron of the Palestinian political camp (including what may be the military adversary Israel is most anxious about, Lebanon’s Hezbollah), presented a lucrative opportunity for autocratic powers to swap “antiquated” partisanship for the realpolitik coordination it would supposedly take to confront Iran.

The case for normalisation was aided by a number of parallel factors. For one, Israel was a sub-imperial authority onto-itself, boasting an economic advantage not around the hold of crucial resources, but rather in an over-developed security and technology sector. For those looking to digitise both their foreign and domestic pacification campaigns, no set of ties were more attractive than those with Israel. The most recent set of leaks concerning Pegasus, the spyware produced by the Israeli NSO Group, have revealed the impressive scope of their customers, ranging from Uganda to Saudi Arabia, who see surveillance technology as a crucial defence fortification.

Another factor to be considered was that the Middle East was not the same place it had been only two decades prior, let alone 70 years ago. By the mid-2010s, popular opinion across the region towards an organisation like Hezbollah was far more polarised, with opinions painting a range of sentiments from “heroic” to “blasphemous” to “desperate,” in comparison to the situation only a decade prior, as a former US statesman observed:

Throughout Egypt in July and August there were dozens of demonstrations to protest the war or express solidarity with the Lebanese and often with Hezbollah. On August 4, 2006, for instance, demonstrations in Cairo involving about eight thousand people were timed to coincide with parallel ones in Baghdad, Amman, and Damascus. Many of the demonstrations were organized by the Society of Muslim Brothers, a venerable Egyptian Sunni Muslim group, but they were also joined by non-Islamist opposition groups including the Kefaya movement. If the demonstrations over the course of the war engaged tens of thousands of Egyptians, they were only the most obvious manifestation of a seething anger among the broader public. Egyptians talked openly about this reaction to the Lebanon war after the August cease-fire. What was most remarkable about the demonstrations in Egypt and elsewhere was that the Sunni Muslims publicly expressed solidarity for a trademark Shi’i [sic] party. The presumed Sunni-Shi’i sectarian divide that fascinates a variety of pundits and scholars proved to be a marginal phenomenon, whereas Hezbollah’s example of resistance and its rejection of quiescence catalyzed support among many Sunni [emphasis my own].42

The Syrian Civil War had sharply cooled support for Hezbollah among a number of Sunni communities (and ironically, may have bolstered it among Lebanon’s notoriously unsympathetic Maronite population). In the eyes of the Syrian government, Sunni subjects, particularly those from the countryside, were potential vehicles of foreign radicalism, despite the regime’s survival by no means being built on the cooperation of the Sunni urban elite. On Arabic-language television, including household names like MBC and Al-Jazeera, the accusations against the Syrian government ranged from war crimes to apostasy. These political crises also reflected an “enchantment” of sectarian affiliation (although it was certainly not the first time), as religious identities were posed as antagonistic (i.e. irreconcilable) political identities, a process that had already been unfurling in both Lebanon and Iraq.43 This process, of course, held a striking resonance with the Manichaean, permanent identities established under colonial administrations.44

The Palestinians were caught in the cross-fire of this sectarian calcification. While most Palestinians were of Sunni background, the breadthof Palestinian political ties rendered them suspect. Palestinian parties could enjoy economic and diplomatic support from the Brotherhood-sponsors in Qatar, military aid and coordination from the Shi’a-predominant IRGC, or even ideological commitment from hardened atheistic communist holdouts across Europe. Even the most notorious Islamist faction of Palestine, Hamas, has not been able to escape targeting by other Sunni formations that accuse it of placing nationhood above faith.

Finally, Israel’s thrust for normalisation was animated by events largely happening elsewhere. While the Boycotts, Divestment, and Sanctions (BDS) movement had emerged from the ranks of Palestinian civil society in the mid-2000s, mirroring the strategy of the late Anti-Apartheid Movement, its influence on shaping sentiment in Israel across the Middle East was marginal (as would be the gains or losses). Rather, it was the classic strongholds of Israeli support, the metropoles of Europe and North America, that these calls were most firmly directed towards and, in a piecemeal and uneven fashion, Israel’s once-uncontested support across civil society (speaking only of the United States) had begun to fracture. The strategic logic behind BDS was not that personal boycotts or even university divestment could impart the economic devastation that would put a price for Israel’s ongoing settler-colonial project, but rather that changing sentiment could eventually force a reverse-face at the highest levels of (US) federal authority, without which Israel’s faith in unilateral aggression would suddenly become far less secure. For this reason, ideological victories, even without a clear economic payoff, were crucial.

The other side of this calculus, however, was that waning support for Israel would leave the Palestinians equipped to negotiate their own freedom, a position that had traditionally been bolstered by the range of ties from its large assortment of regional backers. Rare was the anti-colonial movement that was able to achieve complete “self-sufficiency” during the course of the struggle for decolonization. As BDS threat grew to existential proportions in the Israeli imaginary,45 the shortest route to disarming the still nascent movement in the West was to look East.

The State-Within-A-State:

The Border Returned

While Europe was caught in a delirious fantasy about “reclaiming” its territorial borders, for many African states, the border had never been a coherent and permanent enforceable boundary. This owed to the conjuncture of cross-national communities, like the Zaghawa cattle herders that regularly traversed the border between Chad and Darfur, and the weakness of the post-colonial territorial state. Borders could of course be a site of violence, but the tangibility of the border and their enforcement, particularly given limited resources, emerged in moments of political contingency.46

With their “hands tied,” looking to outsource the atrocities necessary to keep their borders uncrossed, the European Union initiated the Khartoum Process. Alongside former enemy Omar al-Bashir, looking for any means to stay afloat amidst the economic collapse Sudan was undergoing, the EU “exchanged 155 million euros in trade, aid, and development funding for al-Bashir’s policing of migration through Sudan, which is considered both a transit country to Libya and a country of origin for migrants and refugees.”47 Border securitisation became primarily delegated to the RSF, now responsible for holding off the “infestation” European politics has come to so thoroughly fear. Echoing Gaddafi, RSF leader Hemedti declared: “We are hard at work on behalf of Europe in containing the migrants, and if our valuable efforts are not well appreciated, we will (re)open the desert to migrants.”48 The RSF were compensated through both the EU and the Libyan traffickers it regularly “sold” migrants to. Not looking for the rural militias to capture all the glory, Sudan’s security establishment, the NISS, joined the fray, both policing and smuggling across the borders of Libya, Chad, Eritrea, Egypt, and Sudan. Even during the tail-end of Omar al-Bashir’s reign, two lessons were immediately clear. One was that the myth of a fixed, spatial border, that secured European identity from invasion since time immemorial, had ceded way to a new variation on its colonial history, to a reality in which it was rapidly expanding across the Global South. The other was that the externalised border was producing a new division of power across African borders, as authority, arms, and aid flowed from state to para-state to anti-state formations.

Burying the Pearl Divers

As the isolation strategy against Iran was gearing up across the Gulf, Omar al-Bashir’s fracture of ties with the Islamic Republic had only gained him partial support. While al-Bashir was keen to demonstrate his pliability to the remnant authorities of the GCC, it was obvious that his actions were rarely to be taken at face value. Moreover, the Muslim Brotherhood association the NCP held was a constant source of institutional tension with its Egyptian neighbor.

The hottest zone of the standoff against Iran, however, was not Iran itself: like the Cold War, the greatest price was to be paid at the peripheries of the conflict, where the tactics of total warfare were expected to be least easily documented and contested. When Houthi insurgents took over Sanaa, Yemen’s capital city in 2014, Iran came under great frustration. Committed to maintaining its firm intervention in Syria, a new war front was unappealing and, like the Soviets who had initially demurred at the PDPA’s plans to takeover Afghanistan, Iran believed in a strategic pragmatism in Yemen, particularly given the relatively light ties it held to the Houthi movement. However, after the Houthis acted and Saudi Arabia began its total war campaign with US blessing, Iran intervened, looking for a “cheap way to bog Riyadh down in an expensive, unwinnable war.” The Saudis’ initial hopes were to squash Shi’ite unrest in Yemen, with the fear that it would percolate to Saudi’s Eastern provinces, where its highest density of Shi’a followers resides. But as Iran intervened, it extended to killing two birds with one stone.

Saudi strategy was simply, following the moral lesson its American patrons had established in Vietnam: “kill anything that moves.”49 Like the destruction Omar al-Bashir had unleashed on Darfur, the violence grew to indiscriminate proportions, reflecting what A. Dirk Moses has called the logic of “permanent security”:

This security imagination [articulated by Einsatzgruppe D, SS-Fuhrer Otto Ohlendorf during the Nuremberg Trials] – permanent security – entailed a radically new temporal structure. It was concerned not only with eliminating immediate threats but also with future threats. Governed by a logic of prevention (future threats) as well as preemption (imminent threats), it strove to close the gap between perceived insecurity and permanent security […] Ohlendorf’s defense counsel called his actions “putative self-defense” (or “putative necessity”).50

Both combatants and non-combatants alike were implicated in the “security crisis” facing Saudi Arabia, the former as actualised and the latter as potential. Justifying the high casualty count, the Saudis would echo formulations once posed by Fascist Italy in Ethiopia, the United States in Vietnam, and now Israel in Gaza: “After verification, it became clear that the building was a medical facility used by Houthi armed militia as a military shelter in violation of the rules of international humanitarian law.”51

If life had no cost in Yemen, then things weren’t quite the same in Saudi Arabia. While aerial bombing allowed minimal Saudi casualties, it could only accomplish a restricted number of goals . But the Saudis were deeply apprehensive of the political costs of “wasting” Saudi life. Instead, Saudi Arabia took to outsourcing its on-the-ground campaign, looking for the mixture of desperation and social abjection that would constitute a critical mass of soldiers.

The RSF had, by now, “pacified” Darfur. Violence remained semi-stochastic, but it was now largely one-sided, with the rebel groups caught up in a web of ceasefire agreements that were to go unheeded by the power wielders. The RSF’s ranks also filled with the masses of that “dangerous class,” the lumpenproletariat. In the course of the 19th Century, the lumpenproletariat was held up as Bakunin’s revolutionary agent, an underclass working outside the confines of formal and regular labour; meanwhile, Marx’s 18th Brumaire had taken the lumpenproletariat to task as the de-classed refuse of the proletariat, incoherent enough to be melded into the vanguard of reaction to suppress the French uprisings of the mid-19th Century. For Fanon, the lumpenproletariat was some synthesis of the colonial peasant and the seasonal labourer of the urban peripheries: unlike the working industrial classes of the colonial era – perhaps best understood as a sort of middle class, given the rarity of industrial urban employment – it held no investment in the preservation of the colonial regime, which had given it nothing but abjection, choosing to throw its stakes with the liberation of the land.52 Austerity in Sudan had dislocated the social classes of the countryside as much as it had those of the city. In addition, the collapse of regimes of social reproduction – built around agricultural and pastoralist economies – had left military employment as one of the only remaining viable economic spheres, particularly for rural youth. In this case, Marx’s analysis was most relevant. The RSF negotiated directly with Saudi Arabia, the money never formally crossing through state coffers, as the RSF sent over soldiers-for-hire – many children – to take the place of Saudi boots-on-the-ground, a perverse extension of the remittance economy:

The Saudis told us what to do through the telephones and devices,” said Mohamed Suleiman al-Fadil, a 28-year-old member of the Bani Hussein tribe who returned from Yemen at the end of last year. “They never fought with us.” “The Saudis would give us a phone call and then pull back,” agreed Ahmed, 25, a member of the Awlad Zeid tribe who fought near Hudaydah this year and who did not want his full name published for fear of government retaliation. “They treat the Sudanese like their firewood.” […] The Sudanese are sometimes deployed to defend the flanks of the Yemeni militiamen who spearhead attacks. But the Sudanese fighters insist they are also the main barrier against the Saudis’ Yemeni foes, the Houthis. “Without us, the Houthis would take all of Saudi Arabia, including Mecca,” Mr. Fadil said.

Trading One Fossil for Another

Structural adjustment – built around the stripping of public assets, the (often start-stop) retraction of subsidies, and imposed austerity – had made Sudan’s primary sector a viable gamble for those countries willing to take on the risk of its “security situation.” Negotiating with Turkey, Omar al-Bashir would agree to allot thousands of square miles for investment, helping Turkey secure its food supply needs. Jordan, Lebanon, the Emirates, Bahrain, and even Saudi Arabia have pursued attractive land across Sudan’s Northern and Eastern states. Sudan’s breadbasket, following the model of African states (pariahs or not), was up-for-grabs by a slurry of multinational corporations, particularly from the “Islamic world.” Recalling Kenneth Pomerantz’s “ghost acreages,” the middle-income and petro-empires of the Middle East have secured their primary inputs – ranging from groundnuts to alfalfa – at the expense of Sudanese hunger. The state plays its role in attracting and then securing these investments – the RSF’s contract-killers in Yemen has led to Saudi investors being incentivized to work in Sudan, while Omar al-Bashir (and now his successors) have granted cheap and long land leases (“less than 50¢ per acre” for “generally 99 years”) and free plentiful water.

Agricultural land grabs were not the only boom to small, private-sector actors. The RSF, alongside other rural militias and the central government, have presided over a global boom in gold prices. Represented in bulk by artisanal and semi-mechanized mining, gold mining was supervised and managed at the local level by armed militants, (formally) held and traded by the central bank, and staffed by internal migrants, seasonal labour, and internally displaced peoples, particularly in the periphery outlying states, (re)producing the urban-periphery divide that no Sudanese regime has been able to supersede:

In the mining sector, the activities undertaken, as well as the conflicts that mining generates at a local level, favour the redeployment of regional territorial strategies on the part of investors and thus reduce the total control that the central government seeks to establish […] This operation differs profoundly from that of the major industrial mines (very rare in Sudan, with the exception of the Ariab company); the consequences of the economic system of such mines are similar to those in the oil economy: two enclave economies that exclude the regions and most of the national actors. Thus, the new policies perpetuate the asymmetries between the players who are close to the regime and those who are not, but also between the central authorities and local authorities. They simultaneously created the need for a redefinition of relations between regional territories without calling into question the authoritarian and deeply inegalitarian structures established by the government, which is the instrument of its own protection.54

Gold, most importantly, had become a crucial source of hard currency for a country that was regularly deprived of US dollars; and not just Sudan was looking to hold onto it, with the Emirati state becoming one of the largest sources of foreign demand The RSF leader Hemedti – in the years following Omar al-Bashir’s fall – supervised the export of $16 billion of gold per year to Dubai. Mining production at the peripheries had become a crucial arm of the militarised-security apparatus left after the erosion of the state and the loss of oil reserves with the secession of the South.

The Gilded Road towards Normalisation

Formal normalisation with Israel wouldn’t be achieved until after the fall of Omar al-Bashir, but its negotiators were high-ranking nodes in al-Bashir’s circle. For Sudan’s NISS, Israel was something like Disney World, a country willing to sell arms and security, regardless of the bidder (that is, excluding those with extensive Palestinian contact).55 This had meant backdoor engagement with a range of Sudanese governments,56 including al-Bashir.57

Israeli interest was two-fold. Normalisation with Sudan represented a fracture of “Arab” support for the Palestinians, but it also meant a step forward in Israel’s attempts towards improving its standing in Africa. The cold reception Israel received across African postcolonial states was, in part, the lingering influence of the Cold War: Israel, alongside Taiwan, were ready arms purveyors, particularly for the African colonial regimes in South Africa, Rhodesia, and the Lusophone territories.58 With the growing strength of BDS, the active comparisons made between Israel and South Africa, as well as the growing ties Palestinian activists had forged with Black Lives Matter, had particularly unsettled Israel, with the worry that the state, alongside its supporters, may become associated with the “stench” of colonialism and racism.

The second pillar of Israeli interest was far more personal. Sudanese refugees, fleeing crimes against humanity in sites like Darfur, had steadily entered Israel over the years. The MK Miri Regev had likened the Sudanese to “a cancer in our body,” while mass demonstrations among Israeli citizens had unfurled into lynch mobs against asylum seekers within the state. Like the EU, Israel had a “crisis” that needed to be resolved. There was also a unique settler-colonial edge to this crisis. After an Israeli court ruled in favor of deporting 1500 South Sudanese refugees, the interior minister declared: “This is a war for the preservation of the Zionist and Jewish dream in the Land of Israel.” There was an underlying fear: if Israel were to become a haven for (non-Jewish) refugees, could it remain a “Jewish State”? And if it couldn’t remain a “Jewish State,” would it be finally forced to accept the repatriation of millions of Palestinian refugees?

From the Sudanese end, normalisation with Israel allowed a unique diplomatic overture between an Islamist dictatorship and liberal elites, particularly those among the diaspora. The latter’s support had accumulated over the years of the NCP’s uncontested rule. For one, if the crimes of Omar al-Bashir could ultimately be attributed to the racial-Arabist complex of power holders in the country, then support for Palestine carried with it the stench of being the most notable “Arabist” cause. The logic was neatly mirrored by the Islamist undertones that now animated the Palestinian cause, alongside the tacit (and sometimes fervent) approval of liberals to the War on Terror enterprise. Omar al-Bashir only strengthened this conviction, regularly wielding the antisemitic accusation that any form of opposition to his rule amounted to a “Zionist plot.” Normalisation may have been advanced by the genocidaires of Omar al-Bashir’s military-security apparatus, but it also held the allure as a shortcut to rejecting the Arabist-Islamist complexes of the riverine elite.

More important than domestic “consensus-raising,” however, was the modest force of the United States. Donald Trump, tapping into evangelical fervour for a “repatriated” Jerusalem, backed the so-called “Deal of the Century,” while also pushing forward regional normalisation of Israel. Saudi Arabia, still reticent to be at the forefront of what its elites worried might erupt a social backlash, encouraged Oman, a small vassal state then under the tutelage of Sultan Qaboos, to be at the vanguard of Gulf normalisation, publicly hosting Israeli officials in 2018. The Sudanese economy, largely at the mercy of American sanctions that had throttled the country’s currency reserves for decades, was offered up as an award for the price of normalisation. In the moments following Omar al-Bashir’s fall, Saudi Arabia and the Emirates helped broker communications between Sudan and Israel, through its head of army – Burhan – and its RSF leader – Hemedti. Israel, for its part, promised to convince Congress to lift sanctions on the state. Setting aside the ideological contestation around normalisation, it was clear that Sudan’s rejection of normalisation would only enhance its pariah status, while normalisation suggested a direct pathway to economic integration. Meanwhile, the patron-clientele relationship between Sudan and the Gulf, with Burhan and Hemedti as its intermediaries, was assured to provide “crucial leeway to resist popular demands for civilian rule, shaping a lopsided balance of power that allowed the generals to navigate a period of mass mobilisation.”59

The Long Winter