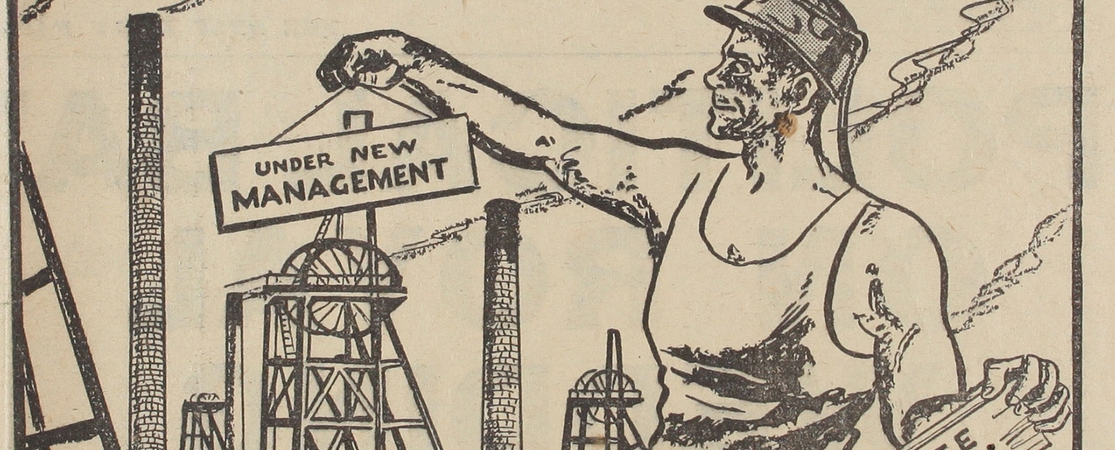

Public ownership is popular, was a key feature of the last two manifestos and is necessary to address the ecological and regional crises. Only Rebecca Long-Bailey takes it seriously.

Throughout the ongoing Labour leadership contest, the three remaining candidates – Rebecca Long-Bailey, Lisa Nandy and Keir Starmer – have been repeatedly quizzed on their attitudes towards public ownership of various utilities and services. Unfortunately, for those of us looking for clarity from candidates on this issue, their responses have frequently been vague and, at times, contradictory. Rebecca Long-Bailey stands alone in discussing public ownership with the seriousness that it deserves.

A key distinction between Corbyn’s tenure as Labour leader and that of his predecessor, Ed Miliband, has been the Party’s willingness to embrace the nationalisation of key services. While Miliband sought only to create a new publicly-owned train operator that would compete with and “challenge” the private firms, Corbyn committed to the complete nationalisation of the railways. And whereas Miliband was prepared merely to increase regulation of the private water and energy companies, Labour’s 2019 manifesto promised to “put people and planet before profit by bringing our energy and water systems into democratic public ownership.”

With public ownership of key utilities both popular with the public and a key feature of Labour’s last two manifestos, it’s likely that the Party’s membership would reject any candidate who openly jettisoned too many of its 2017 and 2019 General Election commitments. Yet Rebecca Long-Bailey is the only candidate who has not fallen prey to constructive ambiguity on the topic of public ownership.

Long-Bailey supports public ownership of rail, energy, mail, water, and broadband, and speaks with authority on the topic. It should come as no surprise that she has been able to confidently and expertly set out her ideas given that she has spent the last four years drawing up plans to radically democratise the economy. Since 2017, she has acted as Shadow Secretary of State for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy and, before that, worked under John McDonnell in Labour’s Shadow Treasury team.

The seriousness with which Corbyn’s Labour took public ownership was signalled, in June 2017, when the Party released the ‘Alternative Models of Ownership’ report, which had been commissioned by Long-Bailey and McDonnell. The influence of this report, which called for the expansion of cooperative, municipal, and statist forms of ownership, can be seen in Labour’s subsequent document ‘Bringing Energy Home’. This 2019 report, which was developed by Long-Bailey’s office, outlined the Party’s plans to “bring energy networks back into public ownership, for the interests of the many not the few.”

This programme would have seen a Labour government nationalise the companies that own energy networks which transport electricity and gas across the country, including the National Grid. Public-ownership and control over these networks is particularly important in a world ravaged by climate change. As the report states, energy networks “that are owned by the public and responsive to the public interest will be able to prioritise tackling climate change, fuel poverty and security of supply over profit extraction, while working with energy unions to support energy workers through the transition.”

The report set out, in detail, the practical steps through which privately-owned companies would be nationalised and a new National Energy Agency could be created and managed. The aim of this ambitious project would not be “a return to the distant bureaucracies of the 1970s” but rather “a model of public ownership that is more decentralised, democratic, transparent and accountable than Britain has ever seen before.”

These policies, which were formed in collaboration with grassroots activists and trade unions, were a crucial component of Labour’s Green Industrial Revolution, which was, again, spearheaded by Rebecca Long-Bailey. Democratic public ownership was at the heart of Labour’s response to climate change because, as Long-Bailey made clear, the “neoliberal approach of substituting citizens for consumers, regulation for voluntary corporate action, individual choice for democracy, and democratic institutions for multinational corporations is never going to protect our environment.”

Public ownership of utilities would also allow a Labour government to provide coordinated, strategic investment in areas of the country which had been decimated by “decades of deindustrialisation and austerity”. Thus, for Long-Bailey, protecting the environment, democratic public ownership, and the rebuilding of deindustrialised areas are not only complementary but mutually inclusive. As she put it in November of last year, “Socialism or barbarism might be a cliché on the left, but when it comes to climate change, the choice looks inescapable.”

In sharp contrast, days after Labour’s election defeat in December, fellow leadership hopeful Lisa Nandy proclaimed that “If I’m honest, I think nationalising the energy companies is a waste of money. Disrupting them by setting up municipal energy companies [and] energy co-ops around the country is a much better route”. In a recent statement to Labour for a New Green Deal, Nandy also wrote that during her time as Shadow Energy Secretary, she “called for communities to take on the power of energy monopolies by helping community-based energy companies and cooperatives to disrupt their power.”

Is nationalisation of the privately-owned energy networks unnecessary then? Could a Labour government seriously tackle the climate crisis and take on the greed of private energy companies just by supporting new municipal energy companies and co-operatives?

No. As the ‘Bringing Energy Home’ report argues, “Private ownership of energy networks has led to excess profiteering at the expense of investment in infrastructure. Regulators have been unable to keep in check the profit maximising that is a structural consequence of granting private ownership over natural monopolies.” Establishing co-ops and municipal companies would do little to deal with these structural issues as community-owned companies struggle to compete with, and meaningfully ‘disrupt’, the Big Six companies. The troubles of Nottingham Council-owned Robin Hood Energyreveal the pitfalls of establishing individual municipal companies without altering the privatised system within which they operate.

Therefore, nationalisation of the energy supply is not in opposition to the expansion of municipal and cooperative energy companies but, rather, a precondition of it. As Labour already set out in ‘Bringing Energy Home’, nationalisation is “required as a backstop to community control, to ensure that decentralisation reinforces rather than undermines shared regional and national infrastructure, and allows for the pooling of resources needed to guarantee universality of supply most efficiently.”

In fact, Nandy’s views on nationalisation put her at odds with her current backers at the GMB. In response to Long-Bailey’s plans to nationalise energy networks, the union’s National Secretary Justin Bowden said that the policy meant “Returning energy networks to where any natural monopoly belongs – under public ownership”.

Like Rebecca Long-Baily, Nandy has signed up to ten pledges on public ownership set out by We Own It, including the commitment to “to replacing the privatised transmission and distribution companies with publicly owned national and regional companies which are democratically run and accountable to the public”. How does Nandy square this pledge with her view that nationalisation of energy companies is a “waste of money”? Does her support for cooperatives and municipal companies operating alongside private companies amount to “replacing” the privatised companies? That seems a stretch.

At a BBC hustings, Nandy went further in rubbishing Labour’s 2019 manifesto commitments as she announced that “We cannot carry on going around as a party making promises to nationalise everything or slash tuition fees.” She then went on to say that the Party “haven’t got a clue how we would do it and how we would pay for it”.

Despite the fact that Labour’s 2019 commitments to public ownership were costed and, as the Bringing Energy Home report demonstrates, well thought-out, Nandy’s statements may well have rung true to BBC viewers. There was, sadly, a perception among the public – stoked by Tories and their allies in the media – that Labour’s 2019 manifesto policies were unrealistic. Ironically, despite her dishonest portrayal of Labour policy-making, Nandy may have gained admirers for her ability to tell supposed ‘hard truths’ to Labour members.

Of course, as we have seen over the last five years, any Labour MP willing to condemn Corbyn‘s economic programme will get their moment in the sun. But, having done so, Nandy appears, at best, inconsistent and, at worst, duplicitous. Following her hustings performance, We Own It asked Nandy to clarify her statements and released a video refuting her claims about public ownership. No clarification has been forthcoming from Nandy.

Labour for a Green New Deal was also distinctly unimpressed by Nandy’s statements, giving her a mere four out of ten on her commitment to public ownership. In comparison, Rebecca Long-Bailey received ten out of ten. As the group wrote, Nandy’s habit of speaking “in terms of ‘common ownership’ rather than ‘public ownership’ is worrying and potential cover for reneging on models of public ownership necessary for a GND.”

The frontrunner in the leadership contest, Keir Starmer, is also fond of the ambiguous term ‘common ownership’ and deploys it frequently. His personal ten pledges to the Labour membership included a commitment to “Support common ownership of rail, mail, energy and water”. Does this commitment refer to supporting co-operatives, like Nandy, or does Starmer back the systemic nationalisation envisioned by Long-Bailey? Starmer makes this (deliberately) unclear.

And, like Nandy, his commitment to We Own It pledges fails to withstand scrutiny. He has signed up to the We Own It pledge of “rolling out full-fibre broadband for all through a publicly owned broadband infrastructure provider.” Yet, when asked by the CWU about Labour’s specific manifesto commitment to nationalising Open Reach, he stopped short of supporting the 2019 policy.

Instead, Starmer wrote in vague terms that “Labour was right to seek to address the current failure of the free market to provide cheap and reliable broadband for all”, that the Party must “now hold the Government to account” on this failure, and “highlight the impact that poor broadband access has on local communities and the economy”. Perhaps We Own It should ask Starmer to clarify these Miliband-esque statements too.

On Keir Starmer, Laura Parker has written that it “would be self-defeating for him to say one thing then act otherwise.” There are, of course, many examples of politicians doing just that, including Labour leaders, but it’s also unclear what Keir Starmer is saying about public ownership. Does he support the nationalisation of Open Reach and energy companies? Despite the fact that he has been asked these questions, we still don’t know.

The seriousness, consistency, and detail with which Rebecca Long-Bailey has formulated policies on public ownership places her in stark contrast with her competitors. It is hard not to suspect that, given their ambiguous and contradictory statements, Starmer and Nandy will abandon the more radical of Labour’s 2019 economic policies. Yet, because of the popularity of those policies among Labour members, neither candidate is prepared to be entirely forthcoming and forthright.

Corbyn’s time as Labour leader has undoubtedly shifted the Party to the left, and that is to his credit, but that shift is eminently reversible. Members have very little control over their party’s policy-making and the next Labour leader could quite easily scrap the transformative economic programme that has been built up since 2015.

If Labour members value the socialist programme that Long-Bailey was instrumental in creating, they should protect it by backing her in the leadership contest.