Ireland has a long and proud tradition of struggle in relation to land and housing. This includes the massive mobilisation of the Land War in the late 19th century, the Republican Congress-led organising in the Dublin slums in the 1930s, direct actions, including eviction resistance and building occupations, carried out by the Housing Action Committees of the late 60s and 70s,1 and the huge rent strike by social housing tenants led by the National Association of Tenants Organisations (NATO) from 1970-1973. This has been followed by the more recent cycle of housing struggles in the wake of the financial crisis.

However, the inspiring history of Irish working class and tenant organisation, including many important and lasting successes, is not very well recorded or widely known. According to the researcher and Living Rent Glasgow member Neil Gray, housing struggles in general are poorly recorded for various reasons, including because the key protagonists have often been women, because there has not been much institutional or financial support by political parties or trade unions and because struggles regarding housing have, in orthodox Marxist theory, often been regarded as secondary to those in the workplace.2 In addition, grassroots housing campaigns are often short-lived in terms of their organisational form, and have not left behind extensive records of their actions. Last, there is a basic economic interest on the part of elites in suppressing awareness of the collective power of tenants and working class people, including how that power has been wielded successfully in the past.

This gap in collective memory is a problem for contemporary housing activists because it prevents us from analysing what forms of organising have succeeded or failed in different circumstances. In practical terms, it makes it more difficult to make connections with previous generations of activists who are likely to have valuable experience and knowledge, and to connect with established community networks which is necessary to build a wider community base.

Aiming in part to address these issues, the training and education working group of the Community Action Tenants Union (CATU) Ireland organised a workshop earlier this year on the history of housing struggles in Ireland (available to rewatch here). One of the takeaways suggested was for union members to research the history of struggles around housing in their local areas. Taking this lesson on board, my local CATU branch in Dún Laoghaire, Dublin, started a project to research the radical history of our area, including past episodes of mobilisation in relation to housing. We hope this will provide the basis for actions such as a walking tour on the radical history of the area.

As part of this work, I came across an interview in the Irish Left Archive with Colm Breathnach, who was an activist in the Workers’ Party3 in the 1980s and 90s in Dún Laoghaire and was elected as a Workers’ Party councillor in 1991 (he later joined Democratic Left,4 of which he was a member until 1994, after which he served as an independent socialist councillor until he resigned his council seat in 1997). In the interview he mentioned that he had been involved in a campaign to improve the conditions in social housing in Dún Laoghaire. I contacted Colm, and he generously agreed to talk in more detail about his experiences and the approach to organising that they had adopted.

Colm’s account offers particular insight into the tensions between direct action and electoral politics. In the context in question, this was related to the overriding focus of the Workers’ Party on gaining control of state power through winning elections, which led to a lesser involvement in social agitation than in the party’s early years. As Colm describes it, this meant that the energy generated by the housing campaign he was involved in was channelled back into the party’s election campaigns and ultimately dissipated.

However, it is important to note that this electoral focus was a response to the failures both of struggle by the party’s armed wing (the Official IRA), and that of earlier forms of housing activism in which it had been involved, such as the Dublin Housing Action Committee (DHAC). The tactics adopted by DHAC, such as building occupations and squatting, were thought to have alienated the broad mass of the people (a 1971 party pamphlet described them as ‘left wing adventurism’). Overall, though they are grounded in the specific circumstances of socialist and republican politics in Ireland, these tensions between radical and dramatic forms of action and building mass movements, including political parties, are likely to be encountered by many movements.

The rest of the article is an edited account of my conversation with Colm, which focuses on these and related themes. I hope it will be interesting and relevant to contemporary housing activists.

Previous housing struggles in Dún Laoghaire, and the Workers’ Party’s involvement in community organising

To put it in context, from around 1982 and until 1992 I was a member of the Workers’ Party in Dún Laoghaire and that was the way I became involved. Later I also became a councillor for the Workers’ Party. The Workers’ Party was very strong there and was based strongly in the working class communities. I have a very different political view now than I did then, but that was the way I got involved in the struggle.

There was a history of struggle and housing action in Dún Laoghaire going back at least to the late 60s peaking in the 70s. One of the people who initiated that was Jack Fitzgerald, who was a left-wing Labour councillor, but activists from Official Sinn Féin and the IRSP (the Irish Republican Socialist Party) were also involved. They were quite active, and they did some direct actions though I’m not sure if it was mostly about private tenants or council housing. In the Workers’ Party we had a bit of a tradition of involvement in housing struggles because the predecessor of the Workers’ Party, Official Sinn Féin, were very heavily involved in the housing action campaigns in the 1960s and 70s. So, there was a template there and there was a history of it, but there was no organisational continuity. When I got involved, there were no housing action campaigns and there was no independent organisation or real campaigning organisations.

We also got involved in housing struggles because we saw ourselves as a campaigning party that was about mobilising people. We could have treated it just as casework. Eamon Gilmore was on the Council at that stage, and he could raise any issue, so we could have just done it like that. But there was a tradition in the party of trying to mobilise people. Some of us had the idea that we weren’t just a party about elections. There was a faction or a wing which said if it’s just about elections you might as well join the Labour Party. That’s probably what led us to take action in the way we did.

Author’s note – there was also a strong National Association of Tenants Organisations (NATO) presence in council estates in Dún Laoghaire in the 70s but, according to Colm, this was no longer the case by the time he became involved.

Organising for better conditions in social housing

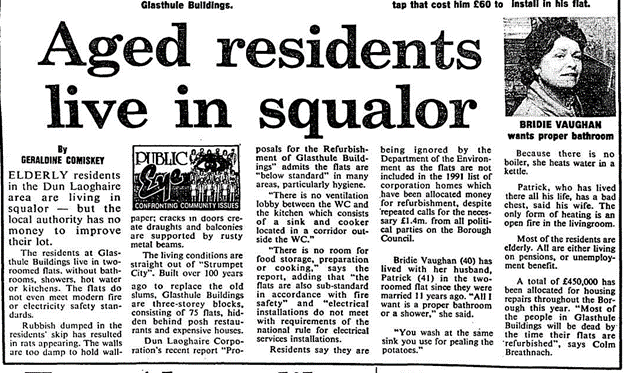

The housing issue came up because we were quite keen on not just being out of the election time and so we always had a regular schedule of knocking on people’s doors and that meant we were picking up issues all the time. So, my memory of it is that we were in that kind of process, just knocking on people’s doors in central Dún Laoghaire, in particular the old streets like Dominick Street and Wolfe Tone Street. We started picking up the obvious issue that most of the council houses had either no indoor toilets or one cold water tap. In other words, they were 19th century houses. And it was 800 houses concentrated in the old centre of Dún Laoghaire but also to be found in Glasthule, in Glasthule Buildings, and bits of Blackrock like St Annes and Emmet Square as well.

We started by having a public meeting down in the Christian Institute in Dún Laoghaire. We doorknocked and leafletted for the meeting and loads of people turned up. Once we saw at the meeting there was a really good response, we said okay let’s form a campaign. We said we’re not going to do it for you but we’re going to help you set it up. So, we initiated a housing action campaign and we did it by doorknocking again. We set up committees in Glasthule and Blackrock and in the centre of Dún Laoghaire. People got really involved who were not part of the Workers’ Party and hadn’t been involved in politics before. We got it going as a campaigning organisation and it took on a life of its own.

We didn’t use direct action, the Workers’ Party was sort of conservative or maybe it was just the era. It wasn’t our thing at the time. I’ve been involved in lots of direct action since then, but in the Workers’ Party we saw that as kind of ultra-left middle class people pissing around. We thought of ourselves as ‘we do it the way that doesn’t lose the support of the people and so on’. We did public meetings and leafletting and lobbying and it did work. We did a lot of publicity with the Southside People, which was there at the time. The pressure started to build, and it began to have an impact. Later we held another big public meeting with a large number of people and this time we invited the councillors along. It was quite rowdy and there was a lot of pressure on the councillors, and they couldn’t say no.

That pressure started to show and proposals were put forward. You’d have to check exactly when the programme was initiated but within about five years all those houses were refurbished, the entire centre of Dún Laoghaire and all that. I’m not saying that was all due to our campaigning but I’m certain it would have been a lot slower. And another thing is I think we got something into the agreement which said the refurbished houses would remain social housing in perpetuity, but you’d have to check that out and see if it has remained the case.

“I know what you’re up to, you and your Bolshevik tactics”

The key to the mobilisation was just constant door knocking, just knocking on people’s doors, talking to them all the time, and having face to face conversations. There was no mystery - that’s what did it. There were pockets of social housing even in Dalkey, in Hyde Park, and we went into every single place, bits of Sallynoggin, Glasthule, anywhere we could find. We knocked on every council house door, every estate we could find, so it was very comprehensive. In central Dún Laoghaire in particular, you had a coherent, long-standing community in a very compact area of social housing. In our campaign we really were organising a community. Once you got a critical mass, once you got one person or one family in each street, it just rolled out by itself almost, because it was an organic community that existed already.

The establishment parties couldn’t do anything about it. I remember being on Dominick Street one time. Dominick Street was the heart of it. There were five of six families on Dominic Street who got really involved and I remember being there and around the corner came Betty Coffey, the Fianna Fail councillor, and Jane Dillon-Byrne from Labour. They came around the corner and saw me chatting to people and I don’t know was it Jane or Betty came up to me saying ‘I know what you’re up to, you and your Bolshevik tactics. I know what you’re doing.’ But they couldn’t do anything about it because they couldn’t do what we were doing by mobilising people.

The relationship between electoralism and autonomous working-class organisation

Looking back in hindsight, it was too closely associated with elections and electoralism. It was semi-autonomous, but we didn’t want any other political parties involved in it. They didn’t bother trying because they knew we wouldn’t let them in. But then once I became a council candidate, we also stood back from it and let it go. But when I let it go, it died and that kind of showed its nature. Although people had been really involved and it had mobilised people, once we stepped back it died and it just transferred into support for the Workers’ Party. The idea was that people would be mobilised and politicised through their involvement in the campaign but what happened was that they were politicised just to the extent where they became Workers’ Party supporters or maybe joined the party. By the time I became a councillor, the organisation, the housing action campaign, had faded away and whatever was left of it was absorbed into our support network. The legacy of it in organisational terms was simply supporters of the Workers’ Party, people who we could rely on to deliver leaflets, to do work for us in elections and so on.

If you put me back there again, I would say let’s initiate this but make sure that the housing action group becomes the focus. And if other people, other political groups want to get involved, let them get involved. Let’s not link it to electoral campaigns and getting elected. Let’s try and separate them out. But these things are always messy. They’re never perfect and never will be. At the same time, It’s one of the most significant campaigns I’ve been involved in and I’ve done all sorts of things since then. I’ve been to Palestine and I’m a trade union activist. I’ve tried loads of different things and in this world, we don’t get many victories. It’s one of the things that I’m most proud of because it changed the lives of loads of people and because it was through the power of their own action. It was won by working class people by their own efforts.

-

Brian Hanley and Scott Millar. 2010. The Lost Revolution: The story of the Official IRA and the Workers’ Party. Dublin: Penguin. ↩

-

Neil Gray. 2018. Rent and its Discontents. London: Rowman and Littlefield. ↩

-

The Workers’ Party is a Marxist-Leninist party which formed from a split in the Republican movement in 1969 between the Provisionals (now Sinn Féin) and the Officials (the Workers’ Party). At the high point of its electoral success in the late 80s the party held seven seats in the Dáil. ↩

-

Democratic Left was a social democratic party which formed out of a split within the Workers’ Party in 1992. It became part of a coalition government in 1994 (at which point Colm resigned his membership) before merging into the Labour Party in 1999. ↩