EDITION: 5th Birthday.

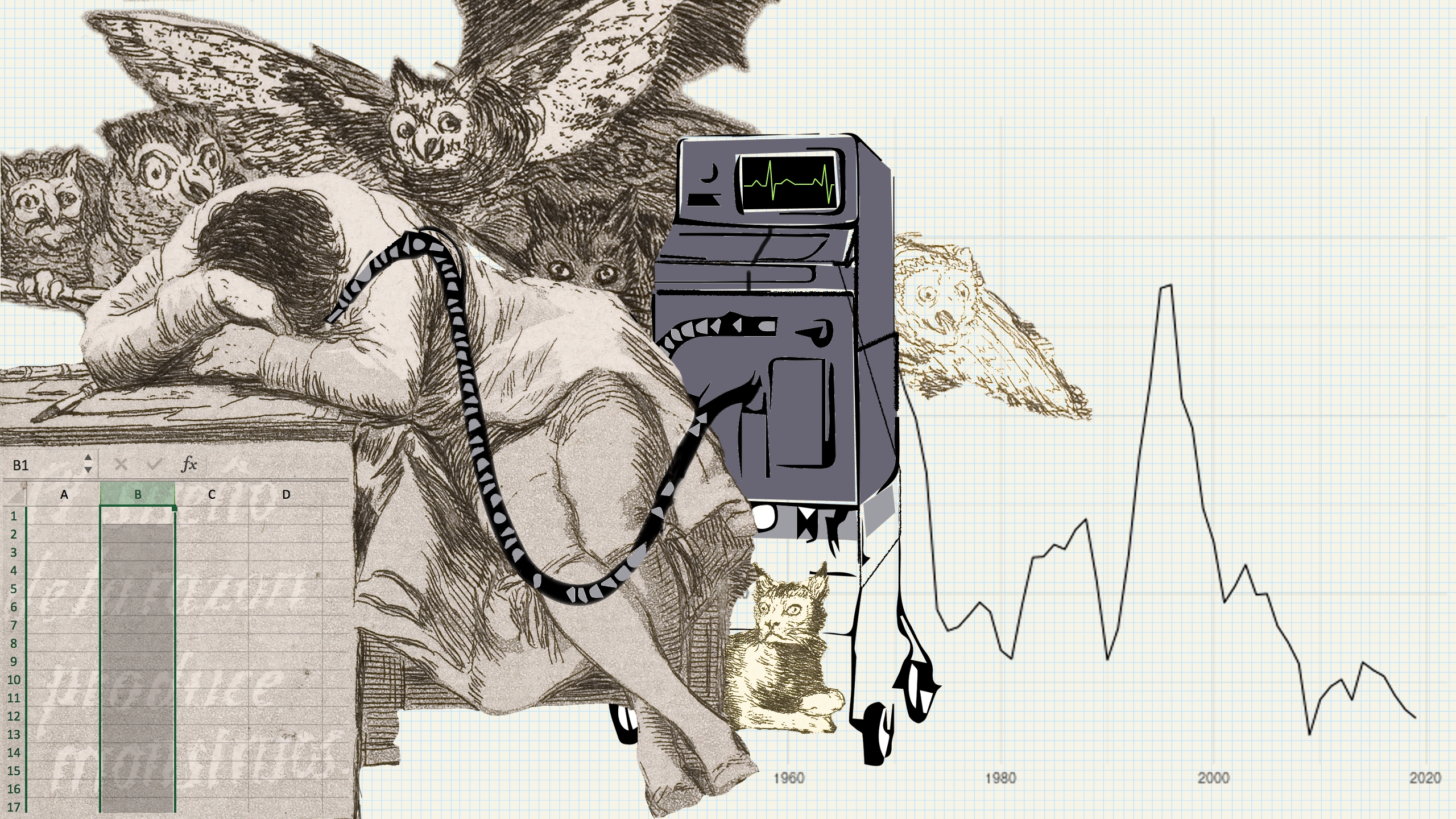

Structural conditions are moving against neoliberal policy solutions— but, absent a counter-hegemonic force, this movement produces monsters.

Few political terms have caused as much confusion and consternation within bourgeois writing than ‘neoliberalism’. It is an indication of how deep rooted and self-evident neoliberal ideologies and practices are that, in its late 1990s/2000s heyday, even naming the dominant ideology of the time made you a radical or a subversive. Even today, some of those who occupy what we euphemistically call the ‘centre’ of politics continue to deny that such a term had, or has, any coherent usage at all beyond the interventions made by Thatcher and Reagan, and perhaps the World Bank and IMF for a period.

There are some within the bourgeois discourse, as Mary Robertson’s analysis in New Socialist shows, who are willing at times to recognise “roll-back” neoliberalism but not “roll-out” neoliberalism, particularly when the roll out phase saw the “promise of increased investment” in as well the “entrenchment of neoliberal logic in public services”. Those who supported or participated in the rolling out of ‘third way’ forms of neoliberalism distinguish Thatcherism from their own programme, a programme which was summed up by Stuart Hall as the adoption of a

Top-down managerialist approach of centralised control, supplemented by the rich panoply of ‘the audit culture’—the exponential expansion of public service managers over professionals at the coal face, unachievable targets, socially uninformative league tables, perpetual monitoring, moralistic ‘shaming,’ the merciless proliferation of pointless bureaucratic detail.

This more technocratic,1 minimally progressive form of neoliberalism can indeed be distinguished in part from the zealous and authoritarian Thatcherite rolling back of the Keynesian state. The notion that such distinctions are sufficient to render the entire concept useless, however, relies on a superficial (and sometimes deliberately obfuscatory) understanding of ideology, where it is taken as a set of shared, internally coherent ideas. If we instead take ideology as more of a common sense, or groupthink, with an ideology understood to be a particular capitalist reality, limiting the parameters of what is possible, it becomes clear that neoliberalism can take a fairly wide variety of forms. Moreover, that variety, the possibility of contestation within those limited parameters, is part of its strength as a hegemonic ideology, with the “progressive” and “authoritarian” neoliberalisms bound together in a “perverse symbiosis” wherein both forms act together to limit emancipatory or radical change, as well as playing out their own internal antagonism within “common sense” neoliberal limits: of privatisation, rentierism, deference to market structures and logics, and moral panics on law and order and immigration.

Neoliberalism limits the possible, including the possible strategies of capital, and the possiblity of even naming it—at least until there is a crisis. In the last major financial crisis, the term ‘neoliberalism’ did come into usage outside of the academy and activist circles, as journalists and economists suddenly sought to name the source of the problems faced by Britain and other nations. Leader writers for the Financial Times abruptly declared the end of neoliberalism (which up until then did not exist), which for them meant the end of the free-for-all trading of complex financial products overseen with light-touch financial regulation. They called for a renewed Keynesianism, with economists like Joseph Stiglitz leading the charge against “the ‘free’ market fundamentalists.”

More critical writers also predicted the demise of the neoliberalism. “Dead, but dominant” wrote Neil Smith. Jamie Peck called neoliberalism a “Zombie”. There was a wholly justified assumption that the ideas of neoliberalism were now rendered incoherent: private over public, the uncritical faith in markets as producing rational and efficient outcomes, competition, individual self-interest needing to be free from the state, notions of entrepreneurial citizenship and human capital. The financial crisis, which saw the state in highly financialised economies like Britain’s spending billions propping up banks and on quantitative easing, was rightly considered to be the end of an era where the ‘market’ (in its various forms) was seen as de facto preferable to the ‘state’. And it was indeed the end of an era: the end not of neoliberalism itself, but of one of its forms. It was the end of what Nancy Fraser calls ‘progressive’ neoliberalism, a form which believed that privatisation, public-private partnership, and light-touch regulation could lead us to improved, social-democratic goals, given sufficient oversight by state or corporate technocrats.

Clearly though, privatisation, deregulation, and the use of private entities within the state did not go away. They have continued to expand, in Britain and in many other nations. Following the crash, a programme of ‘austerity’ in Britain meant that Government departments were stripped back, whilst privatisation and marketisation in education and healthcare was expanded through university tuition fee rises, academy chains, and the increase in the limit on NHS hospitals providing private treatments. The public sector in Britain has been hollowed out to the point that whole departments are struggling fulfil basic statutory functions, such as providing passports, preventative public health measures, ambulances, or clean rivers and beaches.

On a more subjective level, the notion of an ‘entrepreneurial self’ (in which the idealised individual is one who sets out to create a dynamic new business) has increasingly been replaced with ‘the hustle’ and ‘grindset’. These terms have been appropriated from working class African-Americans, for whom they described doing what was necessary to survive, and served up to the readers of Forbes magazine. This rhetorical shift reflects the ever-increasing difficulties faced by anyone without family wealth who wants to start and grow a business in the maelstrom of neoliberal capitalism, where those without such wealth and the educational access required for many public sector careers are consigned to the world of casual ‘gig economy’ work – supplemented with ‘side hustles’. The common thread running through both entrepreneurial selves and hustling is the notion that you just have to work harder—though in the latter case, the extra work is often undertaken merely to survive, rather than to obtain wealth and luxury.

After a decade of cuts and casualisation, we now find ourselves again enveloped in a never ending series of crises which, we hope and pray, may be the end of neoliberalism. The renewed rolling back of the welfare state, the cuts to state investment and government spending on key functions, wage stagnation, sluggish progress on even a capitalist green transition, ‘hard’ Brexit—each of these developments in the wake of the financial crisis challenge the political legitimacy of neoliberalism. In response, states have (re)turned to the more ‘authoritarian’ form of neoliberalism to quell the inevitable dissent to deepening poverty and inequality.

Authoritarian neoliberals in the Conservative Party still blame the ‘progressive’ types for Britain’s malaise, be it through conspiracy theories about ‘woke’ institutions or references to New Labour’s supposed fiscal profligacy. These so called ‘culture wars’ are perhaps wearing a little thin as the crises mount, and as they do, it becomes increasingly clear that paradigmatic neoliberal interventions are lacking in the face of crisis. I think that we can say that neoliberalism is in a coma (rather than dead), though we have good reason to think that its slow death may presage something even more terrifying. Alternatively, the internal tension between neoliberal forms is also giving space for a revanchist version of the technocratic, ‘progressive’ neoliberalism which promises to keep the patient on life support that bit longer, now that the two sides need no longer be unified against their common enemies to the left. This article is an attempt to understand this comatose neoliberal state, at least in the British context.

Neoliberalism is dead, long live neoliberalism!

The premature declaration of neoliberalism’s demise following the financial crash has caused contemporary critical writers to be more circumspect amidst the different sectoral crises we now face: COVID-19, energy, ecological breakdown, food shortages. Adam Tooze argues that it is “hard to avoid the sense that a turning point has been reached”, Will Davies that there has been a “popular and intellectual discrediting” of neoliberal ideas. Wendy Brown claims that neoliberalism is in “ruins”. Several academic special issues have highlighted the various ways in which neoliberalism and the capitalist economy is in a crisis so great that it requires a grand new paradigm to rejuvenate it. Liberal thinkers are centring in on the term ‘polycrisis’. However, this wave of writing often elides the political nature of the crisis, focusing on the various shocks and how they may be overcome, without an understanding of the hegemonic and counter-hegemonic forces which may enact a substantive shift. It is this political crisis I want to consider here: the extent to which these shocks, and a more general crisis within capitalism (from inflation and the inevitable drop in consumer demand) are (or are not) leading to a shift beyond neoliberalism.

Indeed, within liberal writing, that shift is once again being identified on the superficial level. Just as in the financial crisis, the current crisis has seen an uptick in the use of the term ‘neoliberal’, with those who were previously consistent denialists now admitting it has some validity. Mainstream commentators have argued that response to the COVID-19 pandemic could bring forth a new economy—again, a sort of neo-Keynesian one—whilst others declare that Biden’s stimulus and the failure of Truss’s tax cuts mean the end of neoliberalism as a serious proposition.

From the left, James Meadway tries to show that neoliberalism is over by focusing on how big-tech companies are forcing a decisive break with technocratic state management by acting outside of the laws and regulations that make areas like finance possible, which in turn leads to state interventions to limit their size and power—actions that would have been unthinkable to the Blair or Clinton governments. Meadway’s argument, moreover, is not purely ‘theoretical’: it has (and aims to have) political effects. If neoliberalism is over, not only dead but no longer dominant, then this has implications for a left strategy towards the Labour Party. The possibilities for influence are far greater if the unfolding of His Majesty the Economy, has already buried neoliberalism, conveniently changing the terrain of politics without political struggle, and miraculously uniting both Starmer and the left in a post neoliberal project.

The sectoral crises in public health and energy have had similarly unthinkable effects to the power of the tech companies, calling forth state interventions which are out of kilter with the golden age of globalisation and highly technocratic ‘progressive’ neoliberalism. It is a commonly pointed out misnomer to identify neoliberalism simply with ‘free markets’. Instead, neoliberal governments have always been incredibly active in intervening and constructing new, privatised, capital-friendly forms of governance, and shaping individual subjectivity towards entrepreneurial citizenship. The shift to the use of major financial “bailouts”, however, marks a more statist turn towards propping up whole sectors of the privatised economy, not least energy, without then simultaneously either reforming them or changing their models of ownership (recall how financial institutions were re-privatised).

What would it even mean for neoliberalism to die? Even if it is an ideology that dare not speak its name outside of crisis periods, in the sense of a paradigm that guides policy (even when disavowed) it would mean at least an end to (if not a repudiation of): privatisation, the expansion of markets or market-like structures into every area of social life, a belief that competition delivers the most effective outcomes, the drive to commodify everything, and the long process of insulating decision-making from democratic power, often in favour of corporate power.

The pandemic response in Britain did at least undermine some of these ideas and processes. The major bank bailouts and the turn to quantitative easing had already marked something of a departure from the ‘light touch’ ‘partnership’ between government and the financial sector, but these were interventions into a single key sector. The pandemic, on the other hand, required an unprecedented (outside of wartime) set of state interventions which really did go against much of the neoliberal paradigm. The government paid (albeit very reluctantly) 80% of 11.4 million workers’ wages, bailed out whole industries across the economy, and handed out contracts without any pretence at competition. Instead of a ‘partnership’ with business, the rhetoric focused on ‘support’, as if the economy itself was suffering from a virus. But, importantly, in both the pandemic and the financial crisis, governments have made extraordinary interventions to maintain a stagnant and unproductive capitalism centred on asset value growth and rent extraction. Indeed, one of the core claims of competency for neoliberal politicians historically has been their ability to manage inflation—through crushing union power as well as fiscal prudence—and today’s leaders are clearly failing on this standard.

So it may be that, once again, neoliberalism is dying. The lesson from the aftermath of 2008, though, is just how temporary this dying process can be, due to the lack of countervailing forces outside of the highly reactionary conservative right (who, as Melinda Cooper has shown, have long been bedfellows with some neoliberals), and to the continued stranglehold of the professional managerial class (who tend to support the more technocratic approach) on public life. Further, the global derivatives market had reached the same levels as pre-crash 2008 prior to the pandemic, and the British government are enacting further restrictions on trade unions in response to increasing strike action, as well as reforms to electricity markets and the train network that look like further experiments in ‘competitive’ markets where they are structurally impossible. We might even say that these structural impossibilities provide impetus for continued neoliberal experimentation: the constant quest for the perfect private-market form for natural monopolies in areas like electricity generation and distribution provides many hours of work for Tufton Street’s finest thinktank wonks.

Neoliberalism’s future relies on whether it continues to support the interests of the hegemonic bloc neoliberalisation has empowered: wealthy homeowners, landlords, fossil capital, finance. Throughout the austerity period, neoliberal policies have been combined with increasingly authoritarian interventions and populist gestures, which aim to limit political dissent and agitate the petty bourgeoisie sections of the bloc. The leading figures of this authoritarian turn, such as Trump, Bolsonaro, and Johnson, rose to power as elite outsiders, respectively promising to “drain the swamp,” sweep away corruption or overthrow the “metropolitan elite” by leaving the EU. In practice, they used the power of the state to give out contracts and jobs to their friends whilst introducing draconian legislation against workers, unions, and activists.

COVID-19 has undermined the credibility of some of the authoritarian figures who led this turn. With all of the above three having left power mired in scandal, it looks as if authoritarian neoliberalism is facing its own crisis of legitimacy, much like the progressive form did over a decade ago. This varies from place to place. Modi, Orban, and perhaps Erdogan—all remain hegemonic, with new far right leaders in Sweden and Italy looking to emulate them rather than the more chaotic style of Trump. Britain is currently caught somewhere in the middle—the right wing populists seem to be losing credibility and popular support after seeing off a left wing challenge—but it remains to be seen whether there is space for a revanchism of the ‘progressive’ neoliberals, or whether the long-drawn out ‘dying’ presages something even more dangerous.

Authoritarianism as Neoliberal Life Support

The last few years have seen an intensification of authoritarian state violence towards migrants, people of colour, and workers. In Britain, the government has rolled out legislation to restrict political dissent though the Police Crime, Sentencing and Courts Bill, legislation prohibiting Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions, and a series of laws enabling mass deportation to Rwanda or, more recently, to France. This has been the most significant shift from the ‘progressive’ type of neoliberalism. Yet, just like the expansion of academies and university tuition fees, these more authoritarian practices are intensifications, not radical novelties.

Within more mainstream accounts of neoliberalism, authoritarianism is an often under-emphasised aspect, but, as Stuart Hall argues, “authoritarian populism” has been a central means of generating consent for much less popular privatisation and marketisation. Authoritarian populism of some form or another has been a key feature of neoliberalism since the ‘Southern Strategy’ in the USA and the moral panics over racialised ‘muggers’ in Britain in the 1970s. With the Conservatives now ever more reliant on an ageing, reactionary segment of the population, separated by property ownership, inflation level pension rises, and retirement from the reality of the economy on which most working age people are dependent, they are as laissez faire as ever about turning up the authoritarian dial and closing down avenues for political dissent.

And these authoritarian interventions are not simply ‘populist’, or solely centred around state violence. There is an authoritarian statism (as Poulantzas termed it)2 towards the very crises themselves: the doling out of COVID contracts to friends of Government ministers, direct ministerial decisions over infrastructure, the reactionary introduction and removal of planning policy, and, more subtly, an intransigent blockage to legislation which is demonstrably needed—e.g. on housing safety following the Grenfell Tower disaster, or regulation of the digital and platform arena—solely to protect the financial interests of Tory party donors.

What is not clear at this point is whether such authoritarian interventions will continue to support neoliberal statecraft (privatisation, market engineering etc) or lead to something substantively different. The authoritarian turn, in Britain at least, was useful in seeing off a left-wing challenge, but it may have unleashed forces that are less conducive to capital accumulation—in part due to Boris Johnson’s laziness, his delegation of the dirty work to his subordinates, and his opportunistic approach to politics. The failure to introduce a more centralised planning system, for instance, showed the tension between the Conservative base (the subjects of authoritarian populist appeals) and the demands of rentier and house-building capital. In other nations, such as Hungary and Turkey, more committed and programmatic ‘strongman’ leaders have been able to form a bloc which aligns the two camps in ways the Tories appear to be struggling to do absent ‘Get Brexit Done’—leaving them openly courting the far right.

Even with its proponents out of power, authoritarian neoliberalism can still shape the political agenda. The Democrats have been pushed back on many of the more economically progressive features of the programme which got them elected, whilst also having some successes galvanising their base against Republican attacks on abortion and LGBT rights. Other progressive neoliberals are more willing to make common cause with the far right. In France, Macron formed an alliance with the Front National just weeks after calling for “a blockade against the far right”. As Mondon and Winter have shown, there is now an established trajectory of the neoliberal centre mainstreaming the far right with these concessions, unified, more often than not, by a shared hatred of the left.

Neoliberalism is thus caught in a sort of paralysis. Rather than dying away, it is in a coma. It is beset by sectoral crises and major shocks, like the invasion of Ukraine by Russia. Several of the authoritarian populists who promised to turbo-charge the economy have had their personal legitimacy tarnished by their disastrous responses to the pandemic, with the likes of Trump and Bolsonaro invoking conspiracy theories and quack solutions. and Boris Johnson brought down in part by breaking the rules he imposed on others—only for Truss to roll in and destroy what credibility the Tories had left with her short-lived Thatcher tribute act. The authoritarian neoliberal rejection of technocratic, managerial, and expert-led approaches meant they managed the pandemic disastrously. And whilst we should not rule out a turn towards an even more fascistic politics in Britain, the decline of at least some of these populist figures, here and elsewhere, opens up the prospect of a “time of monsters”;3 a revanchist, progressive neoliberalism which has adapted not only to the ongoing crises, but also to the successes (and failings) of authoritarian populism.

Revanchist Neoliberalism and the Authoritarian Trap

Britain finds itself at a crossroads. Whether it will pursue the Orban/Modi route of deepening authoritarian state interventions based on a directly articulated ethno-nationalism and a tightening of the liberal-democratic space, or whether it is in fact time for the supposedly safer, hands of the more progressive, technocratic neoliberals, remains an open question. In the US, in an election held against the backdrop of mass pandemic death, the voters chose the latter; and in Brazil they chose a sort of coalition of the neoliberals and the more social democratic aspects of the Workers Party. Similar coalitions exist in Spain and, until recently, in Portugal; and across Latin America, parties repudiating neoliberalism (often explicitly) have even gained power, albeit in the face of significant reactionary hostility.

In Britain, with the Conservative Party still struggling to recover from a summer of scandal and chaotic crisis management, there is certainly the opportunity for substantial change—particularly as high interest rates hit Middle England house prices and mortgage rates. Unfortunately, those best placed to institute this change appear committed to a revanchist neoliberalism, with those who had been shunted out by the financial crisis and Jeremy Corbyn once more in the ascendency. And, unlike in nations with proportional representation and primaries for party candidates, the neoliberals of the centre left in Britain will not be forced into a coalition with more radical parties, as they have been in Spain.

Instead, the first stage of their revanchist programme has been, in collaboration with the press, to push socialists and social democrats out of public life as much as is reasonably possible. Driven by both ideology and resentment at having their political careers disrupted, the current Labour leadership and party machinery are taking pains to ensure that the next set of MPs are selected from the same professional-managerial backgrounds that most of the PLP come from. Prospective candidates are those which are unlikely to rock the boat and demand substantial reform, with swathes of London-based councillors in comms jobs now returning to the ‘red wall’ seats they left decades ago, lured by the promise of a £80k a year job (plus expenses). The leadership has engaged in what must be one of the largest membership purges ever seen in a nominally democratic political party.

The liberal press have supportd this project with an astonishing omertà. From 2015-19, the pages of the Daily Mirror, the Guardian and the Huffington Post were packed to the brim with stories about internal Labour Party processes and detailed analysis of the Facebook posts liked by local branch officers. Today, similar stories are largely ignored by the same outlets, with seemingly only Michael Crick taking an interest in how future members of the legislature are selected. Even when an independent report, led by Martin Forde KC, identified deliberate electoral sabotage attempts committed by the party and its officials, as well as a deeply racist party culture, the findings barely generated a day’s worth of coverage. MPs who claim to be anti-racists and feminists have suddenly lost their voices, as exemplified by the deathly silence over the treatment of Apsana Begum MP, who is being deliberately targeted by her former abuser through the internal procedures of the Labour Party.

Internally then, the last three years have seen the inheritors to the New Labour project re-establish their positions within the party. These MPs and officials were the people who fought a bitter internal war within the party under Corbyn’s leadership, and the entrenching of these factional positions has allowed them to avoid any reflection on the popularity or viability of their own deeply neoliberal ideological positions. Their years in the wilderness were not spent developing any new ideas. Far from it. When you listen to Rachel Reeves or Wes Streeting speak, they explicitly recycle the terms and logics from the era when they cut their political teeth: ‘magic money tree’, ‘tough on the causes of crime’, etc. Their policy programme, to the extent that we know what it is, picks up where New Labour left off: re-regulating energy, expanding home ownership, increasing private involvement in healthcare, reviving Mandelson’s ‘partnership with business’, and attempting to roll out a corporate-friendly industrial strategy focused on doing, at most, the bare minimum required by the ecological crisis, which they failed to do last time they were in office. Labour’s pitch is that they are best placed to revive the comatose neoliberal patient, to improve economic growth and professionalism in government. Positioning themselves in such a way has won them support from the sections of the professional-managerial class which deserted Labour in 2019. What remains to be seen is if their approach can cohere popular support, or even just sufficient votes from a beleaguered working-age public to get them over the line in the next election. Certainly, the Tory implosion has helped significantly, but there is always the chance that Sunak might steady the ship enough to hold them off.

And this is where Labour faces the ‘authoritarian trap’. So far, Labour have been at best ambivalent about the authoritarian legislation and state practices of the Conservatives. They have admonished some of the most extreme aspects, but have not committed to overturning the Acts that restrict political dissent, and actively supported the government with regards not prosecuting ‘Spy Cops’. Labour’s strategy is to simply avoid taking strong positions in the ‘culture wars’, a strategy which works, at least in the short-term, to diffuse the nonsensical headlines we saw in the Corbyn years. But, as we are now seeing in the US, it also allows the right wing to build support for reactionary, conservative and authoritarian politics, even when they are not in power.

The ‘trap’ is this: in targeting a highly reactionary section of voters whilst deliberately alienating more progressive voters, Labour’s electoral success and legitimacy becomes more and more reliant on an authoritarian appeal. Labour consistently and actively take positions against what is popular with the public—and their own electoral base—in order to impress newspaper proprietors, capital, and reactionary swing voters: see, for example, their refusal to support the postal worker strikes. The authoritarian trap is the likely outcome of this politics, where right wing framings of social issues go unchallenged and structural economic changes are deemed unrealistic. Just as they were following the 2005 election, Labour now face becoming reliant on a small, reactionary segment of the public (secure income, homeowners, retired) and the demands of right wing media for their legitimacy. In this situation, Labour will likely be forced to continue the authoritarian crackdowns as well as crisis-type interventions to maintain the asset bubble, without making a decisive break with neoliberalism—despite the impact that their revanchism will have on the mass of people that tend to support the party whether it’s Corbyn or Starmer (lower income, renters, working age).

The argument from Meadway and others is that structural and global economic conditions are moving against neoliberal policy solutions and ways of thinking. I do not disagree with this diagnosis. The question is: from where are the counter-hegemonic forces coming that can institute a new political era? This is the same situation we found ourselves in following the financial crisis. The conditions were there for a shift from neoliberalism, but neither protests, trade unions, nor electoral politics were able to shift the dial against the entrenched power of capital and the professional managerial class in the Labour Party machinery, the state bureaucracy, or the news media. What we got instead was a conflict within the elite, between progressive neoliberals and authoritarian, reactionary ones, which was then portrayed as a ‘people vs elite’ conflict through the Brexit referendum. The political right were able to cohere popular support for a radical shift in British politics, based in part on the failings of the progressive neoliberals.

Can we say today that the counter-hegemonic forces are any stronger? Union density remains stubbornly low at around 24%, and is concentrated in the public sector. Though there is greater militancy, the scale of action is still highly limited by the Trade Union Act and a servile journalistic class who can be relied upon to reflexively produce the most obscure, self-debasing and inane discourse imaginable when any industrial action occurs. There have been significant protests on environmental and racial justice, but these are now facing increased legal and police restrictions. And politically, Labour have effectively ruled out any serious challenge to the balance of forces within society, with public ownership largely off the table and the main programme being one of more efficient management and regulation of the private sector, alongside some vaguely defined green investment, which they may yet decide to throw on the bonfire of fiscal probity.

What we may face with a Labour government, then, is a party that combines technocracy and authoritarianism, completing New Labour’s shift from a (minimally) progressive, technocratic neoliberalism in the 90s to a reactionary-technocratic form today. The Labour leadership are no strangers to authoritarian actions within their own party, and openly support draconian treatment of protestors and migrants today. We should expect that to continue in government, even if it is combined with a veneer of professionalism and (if we are lucky) some money for public services.

They are also not short of encouragement to do so from the so-called ‘centre’:, the consensus position of the academics and wonks that fetishise polling data is that both parties need to be ‘left on economics, right on culture’. One thinktank has even argued that Labour should target “left authoritarians”, in a surprising volte face from the widespread derision of the previous leadership as ‘Stalinists’. Whatever the electoral merits of this, it is unclear how a government can tackle economic equalities without also tackling social inequality too—but then, ‘left on economics’ in this case would seem to be more about pumping out more subsidies for capital than about redistribution.

One complication to the revanchist plan is the election of Sunak, as he himself is positioned to pursue a similar sort of revanchism. Now that the left are no longer seen as a threat, at least within Parliament, both Labour and the Tories are happy to revert to a more technocratic politics of crisis management, a ‘centrism’ in which politics is suppressed. Sunak has happily supported all the recent draconian legislation, and, due to his connections in the press, has been able to generate the same veneer of competence and professionalism also attributed to Starmer. He cannot really carry off ‘populism’, but he could instead bring with him a technocratic approach to economic management whilst targeting migrants and civil liberties enough to ensure the electoral support of revanchists.

The problem facing either a Sunak or a Starmer government is that neither seem to have a particularly novel or credible programme for revitalising British capitalism. Both stake their legitimacy on their competence, their managerial credentials, but the multiple sectoral crises will surely require more than this, in part because growing inequality brings forth its own tensions and reactions. Sunak and Starmer have, in different ways, been allowed to play politics on ‘easy mode’, because they appeal to the ideology and interests of newspaper editors and important fractions of capital. Nothing either leader has yet said suggests that they have any ideas for reform beyond a broad neoliberal paradigm,4 despite this paradigm failing time and time again.

What is likely is that the growing ecological crisis will only bring further demands for authoritarian state practices from capital and from a reactionary press, whether that be directed towards protestors, migrants, or trade unionists. It will also likely bring further demands for bailouts and stimulus, when another crisis allows capital to hold the public to ransom like they did with the banking crash, with COVID-19, and now with energy. Will governments continue to pay the ransom? At what point will systemic change be countenanced? What vision do they have of a world beyond competition, privatisation, and markets? Or are we to believe that all of these structural features, instituted through decades of neoliberal reform, are somehow unrelated to the present crisis and drastic inequalities?

Both Sunak and Starmer have shown they are intensely relaxed about authoritarianism, even if they do not make populist (or popular) appeals. The problem Starmer faces is that, when the demands for authoritarian interventions come, he risks to eroding his own fragile base of support, whereas Sunak would only bolster his. The only real resistance to authoritarianism would be the support of a popular progressive political movement; however, the current Labour leadership are actively embarrassed to be associated with such a thing. The political philosophy of the Labour right is that they simply need to gain office, and once they are there, they will deliver. What we potentially face with a Labour government, and perhaps a Sunak one, is a reactionary-technocracy, in which major stabilising interventions like bailouts and austerity sit alongside authoritarianism and an institutional stasis, given the lack of interest in changing the politics or economics of Britain substantively, and the difficulties in reviving the neoliberalism which ideologically shaped both party leaders.

The Challenge for the Left

It is clear from the various academic and political articles on the decline of ‘neoliberalism’ that we face a potential shift in politics, one that is global in scale. But as we saw in 2008, that the old world is dying does not mean that the new one is being born. In Britain, the archaic electoral system and the stranglehold of the professional managerial class on political discourse mean that the patient can be kept alive but unresponsive for much longer yet, even if its condition is ultimately terminal. It could well be that the next British government is led by the Labour Party, but this party is not, at present a counter-hegemonic force, remaining wedded to the ‘pragmatic’ expansion of private provision of public services, with digital technology now taking the ‘modernising’ role previously filled by management consultants and internal audit culture. Instead, we will likely see a version of authoritarian politics alongside some minor increases in public spending and attempts at using public money to get the private sector to do something useful, particularly with regard to energy and climate change.

The challenge for the left, is, as always, immense. We have to combat the violence of authoritarian populism as well as the machinations of the technocratic neoliberals. These two fractions are, confusingly, both opposed to each other and willing to unify against the left—as Macron and Le Pen have shown. Labour under Corbyn did give voice to popular discontent with neoliberalism, but it did not shift the professional-managerial class’s institutional power, and was eventually undermined by the rebellion of this class both in the media and the People’s Vote campaign. In other nations, the left has had greater success: Podemos in Spain, the UDC and Left Bloc in Portugal, and the current wave of leftward shifts occurring in Latin America, as Tatiana Garavito has argued.

In these countries, leftist parties have made political breakthroughs thanks to powerful social movements (cohering the unionised and non-unionised), and the possibilities afforded by less archaic electoral systems than we have in Britain. The current wave of strikes are a chance to build the power of workers, but this is both incredibly difficult and is not, on its own, enough.

The particular challenge faced by the left in Britain (and England in particular) is the question of how to advance on the political terrain, where new parties are usually doomed to failure, and with Labour now as actively hostile to socialism and socialists as it has ever been. Rising energy and food costs are showing people that essential systems are broken; however, they are once again being told that there is no alternative to these systems. Direct action movements like Don’t Pay and Palestine Action have been successful in pressuring state and capital, but it remains unclear what the various factions of the left can do to shift political common sense more widely—especially when unions seem to be content with accepting Labour’s revanchism.

Absent an organised counter-hegemonic force, neoliberalism is being kept (barely) alive, with the looming prospect that its death might unleast its even more terrifying ghost. Unlike a decade or so ago, though, there is an alternative programme for non-reformist reforms, which can be organised around in some version of a ‘Green New Deal’. Perhaps the most promising avenue is in cohering this with constitutional changes that would open up the political space for left wing parties to succeed. The open question is whether there is the capacity, resources, and energy to build this alternative in the ruins of neoliberalism—or whether the left will be be caught in its own trap of fighting rearguard actions against the reactionary excesses of ‘progressive’ or ‘authoritarian’ neoliberals. It is the great challenge of our times to make it the former.

-

Blairite neoliberalism could be characterised as technocratic, managerial or techo-managerial, with the state managed through an expanded bureaucracy. The contrast here would be with a hostility to bureaucracy and a tendency towards more direct ministerial interventions as we increasingly see today. See my article, co-written with Simin Davoudi, ‘From post-political to authoritarian planning in England, a crisis of legitimacy’. ↩

-

See Nicos Poulantzas. [1978] 2014. State Power Socialism. Translated by Patrick Camiller. London: Verso, p.202. Authoritarian statism represents “intensified state control over every sphere of socio-economic life combined with radical decline of the institutions of political democracy.” For all the anti-state rhetoric of neoliberals, this could correspond to “roll-back”, a use of the cohered power of the state, and the molecular extensions of control of “roll-out”, as well as whatever undead form we inhabit now. For how, as part of Johnsonism, this extended intervention (particularly during COVID-19) opened up possibilities for corruption, see Adam Blanden’s contribution to the Johnsonism series: “It is hard to avoid the conclusion that a depoliticised, technocratic economy breeds a cronyist, corrupt politics.” ↩

-

Of course Gramsci’s famous line, whether we go for Slavoj Zizek’s translation or Quintin Hoar and Geoffrey Nowell Smith’s, is precisely constituted by a state of undeadness—“the old is dying, the new cannot be born”—and, indeed, by a crisis of consent: “no longer ‘leading’ but only ‘dominant’, exercising coercive force alone.” Antonio Gramsci. [1929-35]. 1971. Selections from the Prison Notebooks. Edited and Translated by Quintin Hoar and Geoffrey Nowell Smith. London: Lawrence and Wishart. p. 276. ↩

-

The only exception is the promise to nationalise the rail network. All I can say is that Blair promised this too and didn’t deliver, so I will believe it when I see it! ↩