EDITION: Bad New Times.

The original New Socialist aimed “to renew democratic socialism” by engineering a broad political coalition. How successful was it?

“The title is intended to signify,” began the editorial of the first copy of New Socialist’s original 1980s incarnation, “not a new brand of socialism but a new departure in the mainstream of socialist activity”.1

The distinction was important. When James Curran, the journal’s first editor, persuaded the Labour NEC to put up a thousand pounds and a subsidised room at headquarters for a bimonthly magazine called New Socialist – rather than the Socialist Quarterly which they had envisaged when they appointed him – he had faced opposition from Dennis Skinner. What was wrong, Skinner asked, with the ‘old socialism’ which he had learned on his grandmother’s knee?2

It was not New Socialist’s socialism, however, which was especially new – at least insofar as socialism is seen as a theory and not a set of practices. What was new was its approach, its attempt “to provide a bridge between public intellectuals, the Labour movement and radical civil society” and “to renew democratic socialism through inputs from Euro-Keynesians, the peace movement, global social justice, industrial democracy, feminists, greens, and the radical local communitarian tradition.”3

Whilst Labour Weekly and Tribune had provided forums for internal party debate, it had been felt that there was a need for a more serious journal of socialist ideas along the lines of Marxism Today but shorn of its formal connection to the Communist Party.4 These ambitions were reflected in the journal’s first issue, which included contributions from Stuart Hall, Mary Kaldor, David Blunkett, Dick Hebdige, Noam Chomsky and (in a small piece in the ‘foreign file’ section) Mike Gapes.

The editors promised coverage ranging “from the tribespeople of Afghanistan to skinheads in Hoxton; from the politics of food in the Third World to the political aspects of new technology; from social relations between men and women to the work of union combine committees.”5 The issues which followed carried pieces from Raymond Williams (“Ideas and the labour movement”, later republished in Resources of Hope), Gareth Stedman-Jones, Bernard Crick and E.P. Thompson, interviewing Michael Foot on unilateral disarmament. The journalist Richard Gott even contributed a “socialist holiday guide”.

New Socialist adopted an open, imaginative politics of the left which drew together thinkers from a range of traditions, attempting to articulate a socialism fit for the times. Sometimes its generosity could be surprising. Chris Mullin recalls an article which he wrote on Roy Jenkins after the former Chancellor and Home Secretary defected to set up the Social Democratic Party. “I was expected to produce a knocking job,” Mullin remembers, “but the more I examined Roy Jenkins’ career the more I came to realise that he had been one of Labour’s most successful politicians.”6 In highlighting the significance of the abolition of the death penalty or the decriminalisation of homosexuality, for example, Mullin demonstrated New Socialist’s aversion to narrowly-conceived “class politics”, and its willingness to carry careful articles which could treat even enemies with kindness.

This pluralism was also reflected in the New Socialist editorial team and its wider advisory panel, made up of the left’s “great and good”.7 In addition to Curran as editor and Seyd as books editor, there was Geoffrey Sheridan as business manager whilst Ann Pettifor oversaw advertising. The advisory panel included such left-wing MPs as Frank Allaun, Judith Hart, Eric Heffer, Stuart Holland, Michael Meacher, Ian Mikardo, Chris Mullin and Audrey Wise. There was also trade union representation, including Jack Jones (retired general secretary of the TGWU), Alec Kitson (its deputy general secretary), Jim Mortimer (the Acas chairman and future Labour general secretary) and Roy Lockett (the deputy general secretary of BECTU). They were joined by activists and intellectuals from the broader left – Raymond Williams, Peter Townsend, Ben Pimlott, Geoffrey Goodman, Mary Kaldor, Ken Coates and Michael Barratt Brown. The advisory panel was a veritable who’s who of the labour movement and the post-1956 left.

That doesn’t mean that the right-wing of the Labour Party was excluded entirely. Dianne Hayter, whose Fightback! documents her faction’s resurgence across the 1980s, was also a member – so too was Patricia Hewitt, initially a left-winger but later a key ally to Neil Kinnock, who Seyd recalls trying to dominate meetings (and being given short shrift by Jack Jones in the chair).8 There was also Baroness Barbara Wootton, by that point in her mid-eighties. Different panellists had different expectations for New Socialist: whereas Curran and Seyd spoke favourably of Marxism Today and the intellectual ferment in Europe, Tessa Blackstone described the journal as necessary because of the then-weakness of the New Statesman and hoped it would appeal to “left-of-centre people”.9

Nevertheless, possible divisions were kept in check by an expansive culture of discussion – an attempt to edit a political journal in a different way. In addition to monthly editorial meetings at Curran’s house, the advisory panel met every three months and discussed everything from the cover design and the people recruited to write pieces to the magazine’s finances – as Blackstone recalled, “in a sense it was kind of like being on an editorial policy body, but also was a bit more than that, because some of those things don’t involve you worrying about the business side because it’s part of what the publishers doing, whereas this was not quite like that.”10

Meetings of the advisory panel are generally remembered as consensual and friendly, with few real rows despite the breadth of opinion represented. Seyd recalls the veteran Jack Jones, at one point its chair, as “tough and strong in his opinions but very wise”. Above all, Curran was singled out for praise – “a very consensual and collaborative editor” who left the books editor to his own devices.11 Blackstone concurred, stressing the confidence which the panel had in him and which perhaps allowed them to pay attention to matters beyond the editorial line.12 They were richly rewarded: after a launch party with 700 people in attendance, the magazine developed a distribution network of 1000 sellers and had a circulation of over 20,000.13 This exceeded expectations – they had envisaged perhaps a circulation of 400 for the first issue, rising to 4,000 by the fifth, but in fact the first issue sold 31,000 copies. The magazine soon had 6,000 subscribers – whilst Marxism Today, in the mid-1980s, managed a circulation of just 7,500 (and peaked at 15,000 towards the end of the decade).14

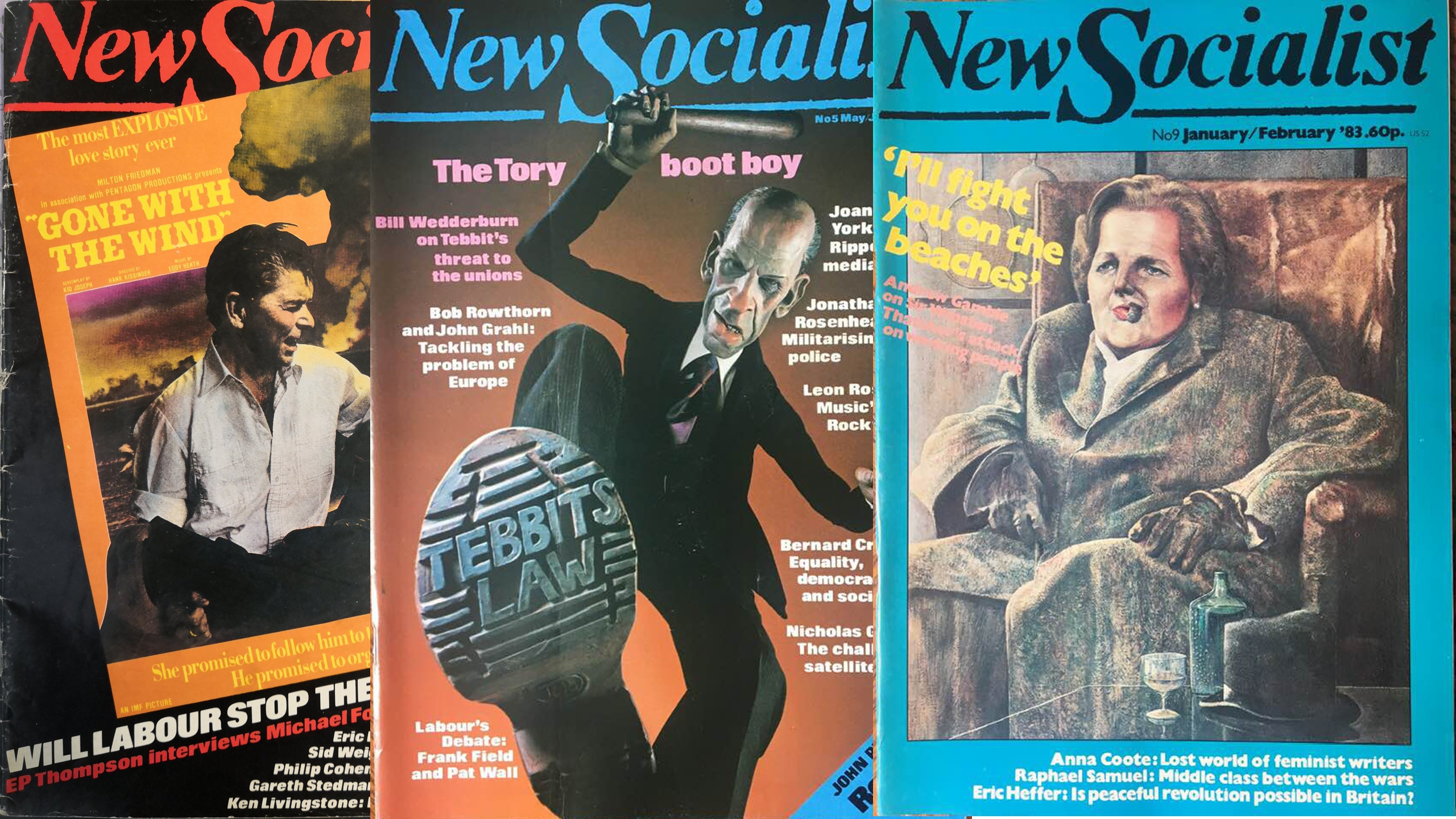

The magazine’s success was aided by Curran’s insistence on forward-thinking design, with front covers noted for being ‘bold, challenging and eye catching’ – including a notable image of Norman Tebbit as a truncheon-wielding “bovver boy”.15 Curran recalls that they looked for examples to the music press, and the magazine made pioneering use of reciprocal flyers with other left-wing magazines, drawing on the marketing example of Readers Digest.16 They also had the advantage of a close relationship with the Labour Party that funded them, hosting three deputy leadership debates in 1981—one of which was televised on ITV.

There were tensions between the ‘old left’, represented on the advisory panel, and the emergent politics which were typically embodied in the New Socialist’s editorial line, from the beginning. Whilst acknowledging him as ‘a genuine ideas man’, ‘a left intellectual with significant European contacts’, Seyd recalls “some pretty testy exchanges” with Eric Heffer, who represented the Labour NEC on the advisory panel.17 The bigger problem was posed by Tony Benn, who Seyd saw as regarding the magazine “as a voice piece for his leadership ambitions and he expected it to articulate his particular viewpoints.”18 His contribution to the first issue sticks in the craw: an ill-considered article on “the need for a national liberation struggle” titled “Britain is a colony”.19 Still, in the early years of the magazine these tensions were productive ones, reflective of an energetic period for the left inside and outside the Labour Party.

If in 1983, Benn and Kinnock remained capable of collaborating on a New Socialist co-published book responding to the election defeat, The Future of the Left, as the 1980s dragged on the differences became harder to reconcile. By 1984, the magazine shifted to monthly publication and Curran – a full-time academic with a heavy workload – had stepped down, replaced by Stuart Weir, who changed its editorial direction.20 Seyd recalls his own role in the appointment, and his initial enthusiasm for Weir, who had experience as a journalist with the Times, but later regretted the decision: New Socialist “became more concerned with ‘life-style’ issues and I think that under his editorship the magazine deteriorated in quality”.21 This shift, occurring alongside a general demoralisation in the left, was accompanied by some of the core contributors’ break with Benn.

Seyd remembers receiving ‘considerable personal flack’ from Benn and Skinner for his article ‘Bennism without Benn’, which outlined the notion (familiar to us now) that Benn’s political project could be continued under a leader free of his baggage. Benn commented upon the piece in his diary, and it’s worth quoting in full:

Wednesday 24 April

Bought the New Socialist, and there was the article by Patrick Seyd called ‘Bennism without Benn’ of which I had been warned. To find a socialist journal carrying an article as personal as this is revolting. Stuart Weir, the Editor, is of the Hobsbawm school, and what the article says in effect is that Ken Coates, Michael Meacher, Tom Sawyer, Stuart Holland and Frances Morrell have all completely deserted me and joined the Kinnock camp and that I am now alone with ‘Dennis Skinner and the headbangers’.

The episode reflected a fracturing of the left which had previously coalesced around Benn into two camps. On the one hand, the ‘new revisionists’ of Marxism Today and the New Socialist’s core contributors, who tacked towards Kinnock and were ultimately rewarded with the appointment of Gordon Marsden as editor in 1987 – after Weir was forced to resign following the publication of an article supporting tactical voting – and the magazine’s eventual dissolution under Tony Blair.22 The “soft left”, still equipped with a new analysis but without the new practices which it had once implied (and the old commitment), played its part in paving the way for New Labour.23 On the other, Benn was left isolated with Skinner and those who’d had little interest in the “new socialism”, and whose politics were never quite the same as his: Bennism at its best, open and creative and generous, replaced by Bennism at its worst, backward-looking, limited and paranoid.

The problems which the first New Socialist faced weren’t only factional. Despite its aspirations to appeal to the feminist movement, a December 1985 survey found that 84% of readers were male – which led Weir to bring in Michele Barrett and Ros Coward as editors. They also suffered from the abolition of the GLC, which had previously been a major source of advertising revenue. The move to monthly publication had been a serious mistake, and only made on the basis of figures which Weir had “fudged” in what Colm Murphy described as “a high-stakes attempt to force the party to give the magazine a larger political and financial commitment.” By 1989, subscriptions had dropped to just 3,100; by 1990, each issue sold, on average, less than 10,000 copies.24 Whereas Marxism Today was propped up by the Communist Party, a cash-strapped and election-bruised Labour Party proved unwilling to step in to plug the deficit of a magazine which had run a surplus from 1981 to 1983. Tony Benn’s note to an NEC meeting when closure was first mooted in 1987 was prescient:

Labour’s policy for the media: (1) Put ads in the Tory press at a cost of £2 million. (2) Close Labour Weekly and the New Socialist. (3) Expel anyone who sells Militant.

The original New Socialist, sustained by a lively approach to socialist problems and a surge in left-wing activity much-diminished after the defeat of the miners and the rate-capping rebellion, met an ignoble end. With an increasingly right-wing Labour Party, to which it was institutionally tied, and a diminished left in local government, the problems caused by divides within the magazine – and a series of poor business decisions – were magnified.

Curran attested that “there is a clear line of continuity between New Socialist in the 1980s and New Socialist now. Both are responses to the crisis of democratic socialism, and both provide an open forum of critical reflection and debate.”25 The “new departure” came, in time, to be reduced to a series of analyses and policy prescriptions, devoid of the energetic, creative, consensual politics which had once animated it – our task, today, is to ensure that the ‘new kind of politics’ does not suffer the same fate.

-

“A new departure”. New Socialist. no.1. 1981. p.2. ↩

-

James Curran, email to the author, 22nd February 2020. ↩

-

James Curran, email to the author, 22nd February 2020. ↩

-

Patrick Seyd, email to the author, 19th March 2020. ↩

-

“A new departure”. New Socialist. no.1. 1981. p.2. ↩

-

Chris Mullin, email to the author, 26th February 2020. ↩

-

Patrick Seyd, email to the author, 19th March 2020. ↩

-

Patrick Seyd, email to the author, 19th March 2020. ↩

-

Tessa Blackstone, phone call with the author, 6th March 2020. ↩

-

Tessa Blackstone, phone call with the author, 6th March 2020. ↩

-

Patrick Seyd, email to the author, 19th March 2020. ↩

-

Tessa Blackstone, phone call with the author, 6th March 2020. ↩

-

James Curran, email to the author, 22nd February 2020. ↩

-

I’m grateful to Colm Murphy, whose PhD research includes the original New Socialist, for these figures and for comments on an earlier version of this article. ↩

-

Patrick Seyd, email to the author, 19th March 2020. ↩

-

James Curran, email to the author, 22nd February 2020. ↩

-

Patrick Seyd, email to the author, 19th March 2020. ↩

-

Patrick Seyd, email to the author, 19th March 2020. ↩

-

Tony Benn. “Britain is a colony”. New Socialist. no.1. 1981. p.58. ↩

-

James Curran, email to the author, 22nd February 2020. ↩

-

Patrick Seyd, email to the author, 19th March 2020. ↩

-

James Curran, email to the author, 22nd February 2020. Colm Murphy has pointed out that this may be slightly incorrect – the magazine probably folded towards the end of 1990, although the association with Blair and Blairism is understandable given the Labour Party’s direction of travel. ↩

-

Richard Hefferman and Mike Marqusee provided a useful account of the publication of the ‘Bennism without Benn’ article, and these divisions, in which they noted that the article was substantially edited by Weir and researched by the journalist Christian Wolmar, and devised by a committee which included Tribune editor Nigel Williamson and the ILEA’s Frances Morrell. In a passage which demands attention from those promoting this strategy today, Hefferman and Marqusee conclude that “The only people in the Party who were liberated by realignment were the old-guard hard right.” Richard Hefferman and Mike Marqusee. 1992. Defeat from the Jaws of Victory: Inside Kinnock’s Labour Party. London: Verso. pp.64-67. ↩

-

Colm Murphy. “The forgotten rival to Marxism Today: the Labour Party’s New Socialist and the business of politics in the 1980s”. Modern British History Workshop. 5 August 2020. Cited with permission. ↩

-

James Curran, email to the author, 22nd February 2020. ↩