EDITION: ECOLOGIES.

The Marxist geographer talks with Tom Gann and josie sparrow about world ecology, Marxist beef, and what it means to be in solidarity with oppressed and devalued natures.

Jason W. Moore’s work—from A History of the World in Seven Cheap Things: A Guide to Capitalism, Nature and the Future of our Planet (co-written with Raj Patel), to the huge range of essays and interventions he makes freely available on his website to—perhaps above all—his book Capitalism in the Web of Life: Ecology and the Accumulation of Capital—has been absolutely crucial in our understandings of ecological Marxism, and foundational for a great deal of what we wanted this edition to be. Jason’s work combines a rigorous, creative conceptual innovation, clarification, and (as Fanon knew to be a necessary, particularly when dealing with the imperialist context1) stretching of Marxist categories with a deep understanding of history and a commitment to rendering it concrete, along with a generosity and responsiveness to the world and its potentialities for change. We were very happy to be able to speak with Jason, and are sp grateful for the carefulness and generosity of his responses. This discussion took place over Zoom, and has been slightly edited for clarity, and to unfold certain points.

To start off, and perhaps for readers of New Socialist who might not be terribly familiar with your work, what do you feel are the really specifically political implications of your work, if that’s not too broad a question?

That’s a huge question.

It’s a fantastic question. I think in the simplest possible terms, it’s about overcoming this false divide between jobs and environment, but that’s too simple. Really, it’s a challenge to what Marx criticises the German socialists for doing in ‘The Critique of the Gotha Programme’… Marx says, “you, the German socialists, have given labour this supernatural power, when in fact labour is not the only producer of wealth; it’s also the soil, the web of life”. And that sets up a quite fascinating political and ideological set of questions, because it’s true: if you look at post-1968 environmentalism, they have adopted their supernatural object, ‘Nature’, that must be saved, that must be protected, and which is separate from the socialist, or communist’s sacred object, which is ‘Labour’. That’s also separated from the second wave feminist sacred object of ‘Woman’, ‘Gender’, however you want to phrase that. We can look at many other social movements who have adopted similar kinds of sacred objects. So, the question becomes, not only how do we engage in an ideological struggle to de-fetishise those sacred objects, but: What are the common threads?

In a nutshell, my common thread is to look at the formation of the proletariat, around paid work, the femitariat, around socially necessary unpaid work, care work, etc., and the biotariat—the work of the web of life as a whole. That last one, the biotariat, is a term I’ve borrowed from the poet Stephen Collis.2 Of course, these are overlapping and interpenetrating realities, and they constitute together what I would call the planetary proletariat. To some that might sound a bit woo-woo. But I think it actually foregrounds the struggle over the relations and conditions of work—of the work of humans, and of the rest of nature—in developing capitalism. So for me, the strategic common ground of planetary proletarian politics is to put together proletariat, femitariat, biotariat into a new practice (and praxis!), and pursue the interconnect abolition of the interconnected relations of proletariat, femitariat and biotariat.

That’s really interesting, and it actually feeds in a bit to some of the other questions we were wondering about asking. Before we get into that—both josie and I are quite interested in how, in these major New Left Review interviews, they kick off with this rather pompously-phrased question: “what is your formation?” So we wanted to ask something similar. In Capitalism in the Web of Life, there’s a really generous acknowledgement of its collaborative character, but at the same time, there’s—and one might want to be cautious with ‘innovation’, but perhaps it’ll do for now—also this very precise conceptual innovation. So, the question about your formation is perhaps what got you to that conceptual innovation and clarification? What were the processes of forming the You that got you to writing that book?

Biographically or intellectually, or both?

Both, I think.

Biographically, I grew up in the working class. I was raised by a single working mother, so I understood at some fundamental level what a feminist working class perspective looked like. I grew up in the really big heartland of post-68 environmentalist struggle in the Pacific Northwest of the United States. Famously, in the 1980s and 1990s, there were struggles to protect what were called the Old Growth forests against logging interests. I was always dismayed at the environmentalist disdain for the working class, and even their opposition to efforts to put together an environmentalism of the working class—which we still don’t have. We have people like Joan Martinez Alier celebrating the environmentalism of the poor, but from a Malthusian perspective, even though he dresses it up. Most environmentalism is what Peter Dauvergne calls “the environmentalism of the rich.”3 It’s the kind of environmentalism advocated by David Attenborough, Johan Rockström—I imagine you saw the interview… What arrogance from people like Rockström, who has spent his life sneering at working class politics and qualitative social science of any critical variety! Here’s someone who is the “chief scientist” for Conservation International, which announces on its website, proudly, its commitment to the financialization of nature. So, my formation – influenced by New Left heterodoxy – led me see these elements of feminism, working class politics, and environmentalism were all elements of a synthesis – and that none was, by itself, sufficient..

I had the benefit of working with the great Marxist thinker John Bellamy Foster at the University of Oregon in the early 1990s, and—despite all the thunder and fury he’s rained down upon me—a good chunk of the world-ecology synthesis is indebted to that conversation. Really, I see much of what I’m doing as a kind of dialectical synthesis of what he’s doing with other traditions of anti-imperialist Marxism, feminist socialism, anti-racist communism, etc. So, for me, that combination of biography and then working with John Bellamy Foster really fed a dialectical imagination.

It was with Bellamy Foster that I learned Richard Levin and Richard Lewontin on the Dialectical Biologist—and I still remember saying to Bellamy Foster in a seminar that this should our methodological text, and he sort of laughed it off and didn’t quite know what to do with that.4 He still celebrates them, but does nothing like what that dialectical imagination does. A dialectical imagination works in the grey zone; it proceeds through variation and diversity, not in spite of these. A dialectical approach understands no individual, no “camp,” has all the answers. That’s why I call the world-ecology conversation a conversation – it’s open ended, experimental, willing to risk confounding mainstream – but also radical – orthodoxies. The Dialectical Biologist pointed me towards a relentlessly creative and connective historical materialism. I mean, Marxists and others cite Marx on the ruthless criticism of everything existing, but they don’t really practice it because there’s this kind of fear of what happens when we go beyond the received orthodoxy. But Marx himself was always going beyond the received orthodoxy, right?

I was, then, very lucky to have a very heterodox group of older, senior scholars who could help me from going off the rails, and really, in their own ways, encourage this idiosyncratic, connective, creative imaginary that, with Capitalism in the Web of Life and the world-ecology conversation, I’ve tried to encourage. The phrase that I use for that is ‘intellectual disobedience’. We need to practice intellectual disobedience against the orthodoxies, against the disciplines. We need to find and sustain the contradictory spaces within the global knowledge factory to open liberated zones where people can do connective, curious, insightful work independently of the disciplines, independently of the disciplining mechanisms of the knowledge factory. Those disciplining mechanisms include, and, by the way, many orthodox Marxists, who seem to be quite terrified of any dialectical reimagination of Marxism. They would surely have denounced Marx in 1876 for revisionism and going away from the true Marxist path. “You, Sir, are not a Marxist,” they would have said in response to the ‘Critique of the Gotha Programme’—in which, by the way, he not only criticises the German socialists for giving labour supernatural powers, but also points out that labour itself is a specifically harnessed natural force. Probably they would call him a monist. But we know Marx was not a monist, because the dialectical imagination always insists on differentiation within the unity.

What I’d share in terms of my formation is that, probably from some good decisions of mine and also some unwise decisions, I’ve found myself in spaces where I was not subject to the full force of the disciplining mechanisms of the university system, and yet managed to find a way. What I’ve tried to do with world-ecology is apply a heterodoxy: to say, this is not a theory, it’s not a line, it’s a web of conversations that look to connect power, profit, and life in long historical perspective, in the interests of developing a revolutionary and socialist praxis for planetary justice.

That’s such a good answer. Let the record show that I’m just nodding along all the way through… that really speaks to me. I’ve never been able to find any place, either within the academy or Marxism, until I found New Socialist. Nobody gets, or got, what I’m doing… well, until I had a bit of Tom’s clout behind me, which says a whole bunch of other stuff.

Patriarchy dies a hard death, doesn’t it?

Well, yes, if it dies at all, would be my slightly pessimistic view.

Well, I have some thoughts on that… we can talk about climate crises and class crises and feminist historical materialism, because nobody looks at the history of these gendered class dynamics.

100%! It’s really interesting, I was just talking to somebody else earlier, who reminded me of this Andrea Dworkin quote: “I always forget I’m a woman, and then I go out into the world and misogyny reminds me”, and that feeling of constantly coming up against a limitation is quite similar to the condition of being proletarianised, as well. So you find yourself, as a working class woman, limited in all these various ways, and also if you want to do something that’s kind of… considered to be methodologically almost a bit ‘wacky’, or to have a method that reflects the politics of what you’re trying to do. In ‘Critique of the Gotha Programme’, Marx talks about how any hypothetical communist society would enter the world bearing the birthmarks of the old order, and quite a lot of Marxists seem to read that and say, “that’s fine, we don’t need to do anything about it now that we’ve recognised it’s the case; we still have to use the instruments of the old order, and somehow a critical awareness will be enough.” It’s the big question of revolutionary Marxism, isn’t it? To what extent are the old tools useful, if at all?

Maybe, connected to that, I’ll ask my Big Capitalism Question. You write, quite early on in Capitalism in the Web of Life, a really arresting line about what if we could understand our cars, and our breakfasts, and our jobs are world-historical activity.5 This is obviously really important, and important for me, in terms of trying to think relationally, including about very minute relations.

It also strikes me, however, that there is a tension there between a sort of neoliberal personal choice discourse: ‘your breakfast is world-historical, so all you have to do is buy this eco-friendly breakfast cereal and you’re fixed,’ and the ‘no ethical consumption under capitalism, so fuck it’ line, which I’m really cynical about because it seems a disavowal of relationality and abandonment of any power or hope to change things, which troubles me.

What reminded me of this was there’s a bit in a Mark Fisher book where he uses the notion of interpassivity (I think it was Robert Pfaller who coined it) to talk about people outsourcing concern for the climate, concern for ecological things, concern for what we’d broadly define as the web of life. There’s this quote where he says, “as long as we believe in our hearts that capitalism is bad, we’re free to continue to participate in the capitalist exchange”6. So, there’s a real tension here: on the one hand, you’ve got the necessity of resisting, personal choice-ism, on the other hand the necessity of not developing this almost Protestant view that as long as the content of my soul is pure, so whatever I do is fine. So, how do we balance those things?

There’s a lot going on in that question! It’s a fantastic question, josie. Let’s begin with one of the signal accomplishments of the mainstream environmentalism that emerged after 1968. Almost single-handedly, the new Environmentalism revived the theory of consumer sovereignty: the idea that capitalism is a plebiscite of dollars, that production choices respond to what people buy and don’t buy. This is of course at the heart of personal responsibility politics, which also enjoys an unsavory relation to Malthus’ arguments about “virtue” which echo across the discourse on “ethical consumption.” It’s instructive to remember that even liberal, left-liberal economists like John Kenneth Galbraith in the 1960s had destroyed the theory of consumer sovereignty. The most powerful critique came from Marxists like Paul Baran and Paul Sweezy, , because they lived in this moment of the full-blown maturation of what they called the “sales effort”.7 The mid-Sixties were a time when this –this gigantic marketing apparatus with “modern advertising” in television and radio, had seemingly colonised everyone’s life. This of course maps very perfectly on today’s era of platform capitalism, the Facebook-isation of everything, in which the product is you—that is, the shaping of your desires, the sense of an alternative. Which of course feeds into the passivity question, because if consumer choice doesn’t make a difference, then fuck it, I’ll do whatever I want.

In contrast, the theory of producer sovereignty, which has long been held by Marxists, says in very powerful ways that the sales and marketing apparatus is fundamental to the expanded accumulation of capital. It is intimately connected with the shaping of consuming subjects, so it very much colonises our mentalités and determines in large degree what we see and don’t see. But, of course, if we’re good Marxists, we see the tendency met with the counter-tendency and the pushback. Today bourgeois individualism remains potent, but I see among younger activists, writers, and students a growing scepticism around consumer-oriented, personal responsibility politics. Even in the US, —and this is quite striking—for the first time since the 1930s or 1940s (and momentarily in the late 60s and early 70s) one can talk about class.

There is a growing sentiment that this consumer capitalist mindset that has been endorsed by environmentalism is entirely false—it’s not consumer capitalism, it’s the capitalism of the bourgeoisie that creates consuming desires through platform capitalism, social media, and the collection of all this data on our lives, the better to shape our desires on a daily basis. Sometimes this is called “data colonialism,” which is fine so long as we remember that imperialism is the bourgeoisie’s preferred mode of waging the class struggle. There’s a class struggle on the level of everyday life that has to be confronted head on. And, just to go back to what you were saying earlier, that’s a class struggle of everyday life, at the level of buying food, shopping for groceries, cooking food, buying clothes, and everything else. All of which is an irreducibly gendered class struggle. And so one of the problems of the orthodox left (and we see this in ecosocialism especially) is really the inability to deal with how the climate class divide fits together with climate patriarchy and climate apartheid. That’s crucial to link the politics of everyday life with the politics at the commanding heights of whatever civilisation we end up living in.

Gramsci in the Web of Life

Your work has this really valuable and productive way of being simultaneously very insistent on the role of the law of value (especially its gravitational role), while also emphasising the non-identity of the value form and value relations. So, there’s this in some ways quite tightly circumscribed idea of wage labour or commodification, opting for this almost austere idea, rather than for those parts of a Marxist or Marxian tradition that try to expand that, and then exploring the relationship between commodification and appropriation. I was wondering how much your work both engages with and can illuminate some of the contemporary Marxist discussions about the value form, on the one hand, but also some of the social reproduction and domestic labour debates, where I guess you have someone like [Lise] Vogel arguing for a restricted conception of value-creating labour, and someone like [Mariarosa] Dalla Costa arguing for an expansive one, wanting to put more stuff, more work, into the category of value creation.8 I wondered how you felt your work engaged with these debates within Marxism, both around the value form and domestic labour.

It’s an outstanding question. There’s so much going on so I might have to give one answer, and then come back and follow up with whatever I left out.

Usually, when Marxists utter the term “the law of value” or the “value form”, your eyes glaze over. Mine certainly did, for a very long time. You’re ready for this extremely turgid, schematic account of how the law of value works, and it’s often quite abstracted from the actually existing relations of production and reproduction, of webs of life, of the history of capital accumulation, and so forth. [Capitalism in the] Web of Life, then, was an attempt not to provide the answer, but to push the value discussion into a very different register.

From the start, the value discussion says there is a double register of the law of value, that I call the ‘law of cheap nature’. And that says, on the one hand there is an incessant drive to reduce the costs of production, especially what I call the Four Cheaps: labour power (including unpaid work), food, energy, and raw materials. This is a logic of capital moment. One other hand, there’s a Gramscian or ethico-political moment of devaluation, of devaluing the lives and labour of “women, nature, and colonies,”9 to quote Maria Mies. So, in other words, valorisation and devaluation, in this scheme, form an organic, differentiated unity.

I point out that, for Marx, the dialectic of value and use-value in fact refers to a disproportionality, between “paid” and “unpaid” work. This connects to my earlier distinction of the Planetary Proletariat, premised on the uneven relations between wage-work and the unpaid work of the femitariat and biotariat. For Marx, value is valorised work – that is, set in motion to create more capital. It occurs within the cash nexus. But remember Marx’s critique for the German socialists? Soils and forests are also sources of wealth, they are use values. Now, use value should not be confused with utility, which is what happens a lot. Use value is, rather, the dialectical negation of value. In the Grundrisse, reckons it is as the antagonism between “economic equivalence” and “natural distinctness.” Use value refers not just to the useful properties of a tree or a blueberry bush, but also to the unpaid work of humans and the rest of nature. What I say in Capitalism in the Web of Life—and I’m trying to tease this out and elaborate this further in my new book—is that for every act of exploitation (of surplus value within the cash nexus, of the proletariat by the bourgeoisie), there is a disproportionately larger quantum of unpaid human and extra-human work.

Now, at one level this is widely registered. We understand that, say, more and more steel attaches to less and less labour power, or more and more bushels of corn attach to less and less labour power—but when it comes to unpaid work there is an extraordinary refusal to see it.

And the final point I would add—this is where I’ve been very much inspired by the work of Claudia Von Werlhof, who unfortunately is almost entirely forgotten… she points out that Nature and Society are these ruling abstractions (think of Marx and Engels in the German Ideology), these ruling ideas, that are treated as real.10 Ruling abstractions are operative guidelines of ruling class power. As von Werlhof and others have made clear, the ruling abstraction ‘woman’ developed through the category of Nature. And Nature, she says, is basically what the rulers say when they don’t want to pay for something. It’s one of my favourite essays, but again because of the patriarchal biases of readers (including me!), and of Marxism, I didn’t come across it until it was too late for Web of Life.

The point about real or ruling abstractions is impossible to overstate. Intriguingly, the most aggressive critiques of Web of Life completely excise the argument, essentially verifying my critique of their economic reductionism. There’s tremendous real world relevance at stake here. At the heart of the struggle for planetary justice is an ideological struggle around these ruling abstractions “Man” and “Woman”, or “Civilisation” and “Savagery”, or what we call today “Society” and “Nature”. These are not semantic quibbles. It’s not just ‘let’s find the right word’, it’s not an exercise in ‘Woke Marxism’—it’s an exercise in the critique of ideology, and these geocultural mechanisms of sexism and racism and Prometheanism (that is, the drive to dominate nature), are the ideological conditions for the superexploitation of the planetary proletariat. Geocultural domination is instrumental to sustaining and advancing the rate of profit. And we know this because capitalism gets rid of ruling abstractions that are not useful to advancing the rate of profit. We don’t need to become metaphysical about this, we need to take seriously historical materialism around it.

Something else I think is really valuable about Capitalism in the Web of Life is, and it was interesting you mentioned this explicitly, is that there is this sort of hidden Gramscianism.

Absolutely!

So, I think there’s a lot of everyday discourse about ideology that treats ideology as largely about securing consent and legitimacy—and obviously that’s a role it has—but then I think your emphasis on ideology as doing more than that, as being present in production or reproduction, as productive (something Gramsci doesn’t ignore but a lot of Gramscians do) has always felt very valuable to me in how we might think more widely about ideology as something that is almost a productive force, including in terms of those devaluations which you’ve discussed.

That means a lot. That was always my orientation, to put together these two moments: the law of value as a law of cheap nature, this moment of cost reduction, and then the moment of ethico-political valuation and devaluation, that’s fundamental. So as you say – probably more clearly than I – that cultural formations, not least those around Prometheanism, sexism, and racism, are productive forces, that’s crucial.

What I’ve come to realise is that much of the unfriendly reception to this argument has completely and totally ignored the critique of ideology and the question of real abstraction. It’s really a shame. There’s a debate that needs to occur. I’ve had many great teachers in my life who said more or less the same thing: what you want to do is to take the object of critique—that is the person or position you’re criticising—and take them at their strongest point. You don’t want to create these straw dog arguments. This is what’s happened with the non-critiques of Web of Life, which remove the question of real abstractions that is at the core of the book. From there it’s inevitable that one creates an undialectical object of critique. It’s effectively impossible to find an opportunity for generative dialogue out of such one-sided presentations.

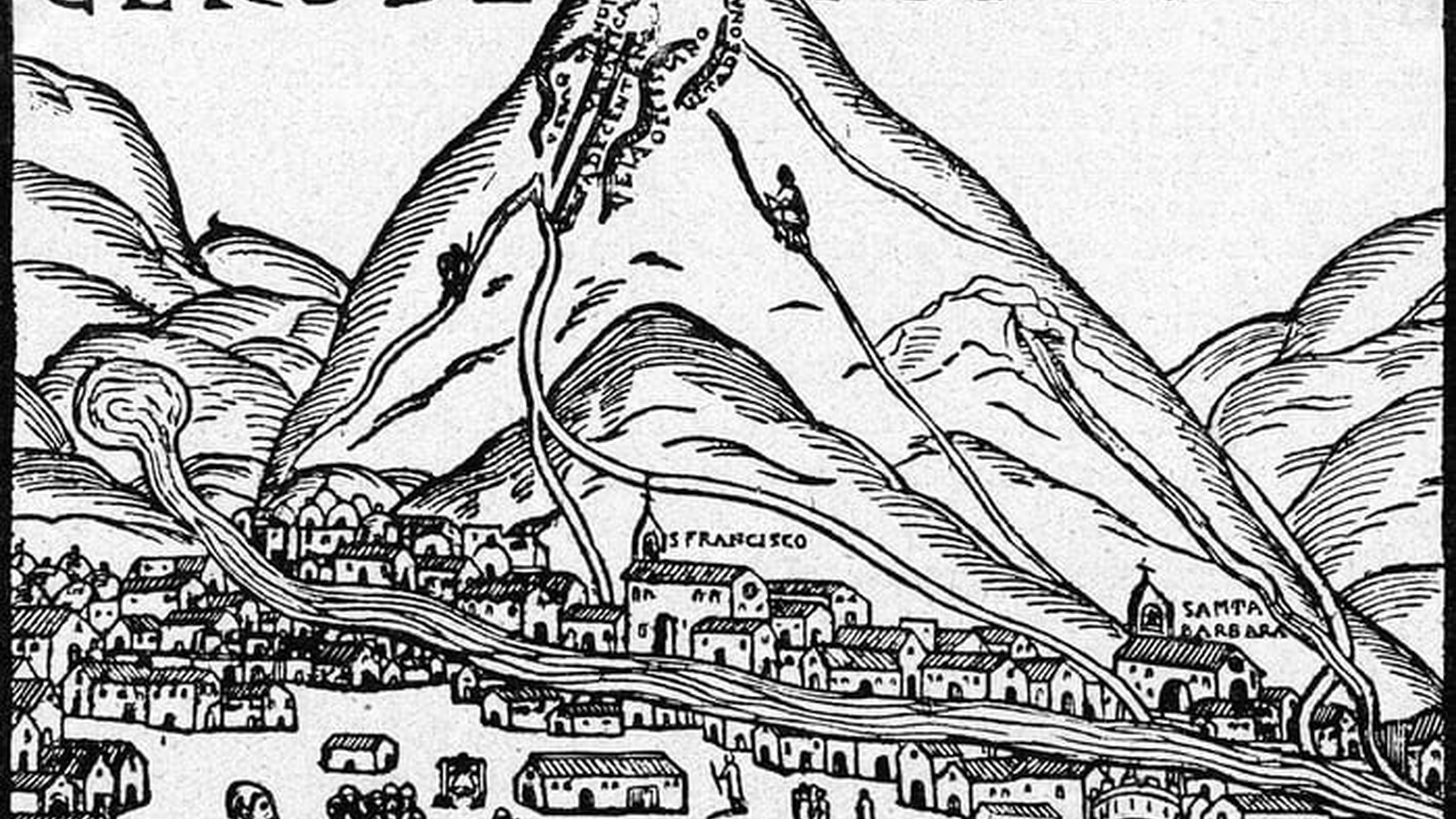

In any event, this question of the critique of ideology is so fundamental, because it goes to this Nature/Society binary. I think what I was able to open up, if just a little bit, was to move this question of Nature/Society dualism from epistemology to ideology and therefore onto the terrain of world history. What I’ve tried to point out is that from the beginning—it’s obvious from the English language, but this happens with the Dutch and the Spanish too—from about 1550 you have the emergence of the modern sense of Society, the modern sense of Nature. Raymond Williams is great on this. Society and Nature emerge precisely in the century and a half after 1550. The timing is important because this was capitalism’s first great climate crisis. At this time, we see the emergence of this discourse amongst contemporaries of ‘Civilisation’ and ‘Savagery’. Of course – you know this living in Britain—this discourse was also an ideology, and it took shape out of the conquest of Ireland? The Irish were ‘Savages’. The expression “beyond the pale” comes out of this experience – the Oxford English dictionary says it doesn’t, but I’ve found a number of contemporary texts that use precisely this language. “The pale” referred to that old colonial line, a rough semi-circle around Dublin, inside of which were the “civilised” English, Anglo-Irish, settlers, and beyond which were the ‘savage and wild’ Irish—‘savage’ and ‘wild’ was the language of the time, just like many colonised people after that.

The language of civilisation and savagery, or what today is Society and Nature, drips with blood and dirt in the most palpable and direct ways possible. Indeed, capitalism has been shaped by recurrent and overlapping civilising projects, Christianising projects, and of course, after 1949, developmentalist projects in which everyone else is un-developed (just as earlier they were un-Christian, or un-civilised).

This kind of thinking – call it “Gramsci in the web of life” – leads to a fundamental political critique of mainstream Environmentalism. As we know, Environmentalism proceeds through a Man and Nature cosmology. One thing we can say is that the thinking that created the planetary crisis – Man and Nature and the Civilizing Project – will not be helpful to transcending that crisis. But I think we can go further. Man and Nature represents not on a practical philosophy of domination, but also a managerial philosophy. Conservationist thought, going back to the 16th century, of course pivoted on resource management. Colonial administration – colonial Peru is a great example, the place where the silver that built capitalism was mined – is another dimension of this. The goal in reclassifying Indigenous Andeans as naturales was basic to the labor mobilization and the geo-management strategy of turning colonial Peru into a gigantic extractive-export platform.

Some readers will know that I write a lot about “Cartesian dualism,” after the great philosopher Rene Descartes, writing in 1630s and ‘40s. As I’ve always insisted, Descartes’ thinking is important because it channeled the zeitgeist. He distinguished between “thinking things” and “extended things” as discrete essences, a move that readily leant itself to the ideological separation of Civilization and Nature that we’ve been discussing. What’s crucial here, however, is not the philosophical point so much as its managerial implications: what Harry Braverman famously called the “separation of conception from execution.” In sum, the managers reorganized production so that “thinking” work is concentrated in the minds of the bosses, and “extended” work is concentrated in the hands of the workers. This was part of a wider systemic movement to restructure production as a series of interchangeable parts – a restructuring that was, as I’ve demonstrated, evident in sugar plantations and shipbuilding centers at the time when Descartes was writing. In other words, the “scientific management” revolution associated with Frederick Winslow Taylor and twentieth-century Fordism was in motion centuries earlier. Now – bear with me! – fast forward to the 1960s, when “systems dynamics” matured. The systems models that led to 1972’s The Limits to Growth were developed at MIT’s Sloane School of Management – in case you’re wondering, the “Sloane” in question was the pioneering CEO of General Motors. Today’s “earth system” models trace their lineage to a management school: whether they are conscious of it or not, they are socialized to pursue “good science” that is soaked through the common sense of the manager. Another name for earth-system science might be Biospheric Taylorism, whose Prometheanism, like capital accumulation, knows no internal limits. Much of today’s Environmentalism – not environmental justice movements, which are very different – embraces the philosophy of planetary management premised, in the final analysis, on Man and Nature, the reified expressions of Bourgeois and Proletarian. Centuries later, we are too often captive to the Cartesian imaginary: of “thinking things” (the planners, the scientists, the bosses) and everyone else, ‘extended things’. This sensibility unifies the history of environmentalist thought from Descartes to Malthus all the way to ‘Limits of Growth’ and today’s Popular Anthropocene.

I think one of the reasons why this framework has always appealed me is that I’m third generation Irish. My entire family is from different strands of people who ran into each other in Liverpool as refugees from the Great Hunger, so all my grandparents were born in slums by the docks. We’re very recently ‘English’ and this was something I was aware of growing up—and then there’s a weird situation of how the city of Liverpool relates to England as often only provisionally English; there’s a version of ‘savages and civilisation’ discourse that goes on. So, to have an understanding of why I’m here—which is the first moment of doing philosophy: what’s happening here, why do I find myself here, in this particular situation?—I can only understand that through British colonialism, really poor colonial management, and then being the reserve army of labour, being part of a subaltern proletariat in a place that already had a proletariat that was undergoing some quite horrific things. So, I think it’s fascinating to me that anyone could disagree with this sort of framework, because it makes so much to me, working outwards from my own experience and understanding.

You mentioned earlier some of Bellamy Foster’s response to your work—interestingly, the Wikipedia page for ‘metabolic rift’ is almost entirely dedicated to the beef between you two! Now that’s what I call World Historical. But anyway… it always interests me to see the upper echelons of the academy rejecting a lot of your framework or analysis in this very strong way that doesn’t make a lot of sense to me. And, I guess one way of understanding it to me, albeit a vulgar Marxist way, is people trying to protect their own class interests. But why do you think you attract such opprobrium?

When you go after the sacred objects and call for a de-fetishisation, that then calls for a different kind of intellectual and therefore political practice. People have personal investments in a scheme of argument or a structure of specialisation. I don’t say that to belittle: they’ve invested their professional and often personal identities into a given specialisation. It’s the product of work, and that that has to be respected. At the same time—and what I’m seeing is a very interesting and encouraging generational divide—many younger scholars are much more open to arguments that transcend the tyranny of academic specialization and discipline.

I’m also the kind of person who is more interested in being interesting than correct… I’m never concerned if people want to take one element and leave the rest. That’s as it should be. In fact, that’s how I open Capitalism in the Web of Life. People should be constantly appropriating, making it their own, pushing it back out—and a lot of times, I’m really grateful! The result is that I see things I didn’t see at first, I’m excited to rethink and renew some of the key elements of what I’m thinking, and to extend it and broaden it. And, for those who have been paying attention to my work, you’ll have noticed that, for example, in this move into climate history, seeing the climate crisis as the result of this trinity of climate apartheid, climate class divide, climate patriarchy was implicit earlier – but now assumes much greater salience. For me, there a constant questioning of previous formulations as I encounter my blind spots. We all have them, and at its best, our political and intellectual communities help us to see something new, and support us to integrate those new vistas. The challenge, from a dialectical point of view, is that integrating new connections requires us to rebuild the intellectual house – it’s not a matter of adding on a new bedroom. Dialectically, the incorporation of new ideas and relations entails a rethinking of the whole.

That of course runs directly counter to an academic world that encourages people to engage in a kind of premature closure of whatever they’re studying. A previous generation’s “expertise” may or may not be relevant; but the academic world often insists upon it. Expertise tends towards the study of… ‘fetishised objects’ might be too strong, but the unnecessary and premature bounding of arguments. A great example of this would be somebody like Andreas Malm, who has written a very useful and sophisticated account of class struggles in English mill towns in the transition from water mills to steam power during the early nineteenth century. That strikes me as entirely relevant, useful, and generative in all kinds of ways. But don’t tell me that the heart of the industrial revolution was the steam engine. Please! I’m not even going to Marx for a defence on this, but not even Marx, if you’re going to be orthodox on this, believes this. It was only the fall in the price of cotton, he says, that allowed for the advent of large-scale industry. Now, what was it that drove the fall in the price of cotton? It was the ‘second slavery’—the revival of slavery, the reinvention of slavery—across the Americas but especially in the American South; the invention of the cotton gin; the dispossession of Indigenous peoples; the appropriation of a strain of cotton, hirsutum cotton, that had been developed by Indigenous people and could withstand the machine milling of Manchester textile mills; then the pushing of the cotton commodity frontier into the American South; and all through it, the audacious expansion of the plantation proletariat. So, please don’t tell me that the story of the English Industrial Revolution starts in England, either geographically or historically! At the same time, I don’t think any of this disqualifies and undermines Malm’s significant contributions, and I have said this many times.

And so what I’m trying to do is to say, there are many more opportunities in the radical left—anarchist, socialist, communist—for intellectual synthesis that could be really useful. I don’t need to accept everything that, say, someone like Malm says about fossil capital to say there are extraordinarily useful elements of that contribution. The alternative I would suggest is an ethics of synthesis, one that draws on the spirit of engaged pluralism, through which our default intellectual procedure is both/and rather than the Cartesian logic of either/or.

World Ecology

I was having a quick search yesterday to see if there’d been extensive engagement by value form people with your work, and sadly there didn’t seem to be that much. But I came across a dire review, and what struck me—and it’s something I’ve seen levelled at your work before—was a claim around the “inaccessibility” of your work. And for me, firstly, this doesn’t ring very true. josie & I got History of the World in Seven Cheap Things for my Dad for his birthday, and my Dad… he’s a bright guy, a curious guy, who did a history degree, but he doesn’t have the Marxist theoretical formation and training that gets held up as being necessary to get your work—but he got a lot out of the book! And then our friend Tom who wrote the Football in the Web of Life piece…

That was great!

I was editing a very early version of that and he had in it, without having read any of your work, “football is in capitalism; capitalism is in football”, so I suggested that he might be interested in your work, and he was saying he found your style very nice and easy and engaging. So I’m interested in how the ‘inaccessibility’ claim works with academic disciplines and disciplining. A thing I come back to a lot is where [Ralph] Miliband criticises [Nicos] Poulantzas for his apparent inaccessibility, and Poulantzas’s response is to say that Miliband’s work hasn’t been affected by politics, or by the class struggle, so he can continue using the same ossified but apparently ‘accessible’ concepts, but Poulantzas has to invent these new concepts, because he’s responsive to the shifts that have happened since ’68; events which demand a new conceptuality.11 I’m wondering if the critique around ‘inaccessibility’ works around this.

I’m reminded of Noam Chomsky’s argument about concision. He points out in Manufacturing Consent, and other places over the past 30 years, that one of the ways in which ideological control is manifest is a ‘stay in your lane’ mindset: don’t try to combine different conceptual elements of historical materialism, above all don’t go back to Marx and Engels and take seriously what they’re doing in texts like The German Ideology. In many ways, world-ecology is “simply” taking their premises and following the dialectical investigations where they may lead. Marx and Engels were remarkably clear and prescient: history must set out from not only the “natural bases,” but also their “consequent modifications” in the course of human history, which is a history of class society—and Marx and Engels include climate change in that as well!

The claims about accessibility cannot be refutable; they are a perfect smear. Such claims have always struck me as peculiar, for two reasons. One is that Capitalism in the Web of Life advances a working set of propositions about how to understand the history of capitalism as an ecology of power, profit and life. It’s not really a work of theory as conventionally understood. It’s a set of arguments, in the final analysis, about turning points in world history. After the book came out, I thought – naively it turns out! – that critics would engage precisely this interpretive terrain: the turning points of world history. But no. Critics, by and large, wanted to disconnect, to alienate, the theoretical-conceptual claims from the world-historical narrative. This was the very opposite of how I wrote the book, and how I’ve written virtually everything before and since. Theory is historically-grounded. Or it is nothing.

Most “critical” theory – Marxist or not – forgets this. There is a flight from history, which is intimately connected with bourgeois ideology and fetishized presentism. This favors premature closure, a certain reification of concepts and camps that resist thinking beyond established sacred categories. Part of the problem is that scholars are rarely willing to step outside of their “lane,” – as we’ve seen – whether it’s value form or ecosocialism or political economy. You can think of all the great work in Marxist political economy over the last 30 years. How much of it takes seriously the web of life? Maybe in a page count, 1%. Sometimes one deals with resources, sometimes a more-or-less anodyne reference to an “environmental” context. My point is not so much to criticise them for not doing it, but to say: Here’s a way, with a few world-ecological concepts, that you could more effectively explain capitalism’s great stagnation by bringing in the life part of power, profit and life.

Bringing the web of life into our interpretation of capitalism’s economic history and its tendency towards overaccumulation crises has been one of my fundamental arguments for the past fifteen years. It connects with this non-debate in eco-socialism quite explicitly. Beginning in 2008, I pointed out that, for metabolic rift thinking, there’s a great lacuna: between the theory of monopoly capital and the ecological reading of Marx’s historical materialism. Such lacunae are inevitable. Effective scholarship always raises more questions than it answers. So I wasn’t taking potshots. Indeed, I was pursuing a synthesis for which Bellamy Foster had already argued several years prior: namely, that the metabolic rift approach to historical materialism should be synthesized with a socio-ecological reading of Marx’s law of value. In this sense, world-ecology aimed at opening space for a world-historical and ecological reading of capitalist history, one in which world accumulation and its overaccumulation tendencies could be explained not merely theoretically, but concretely. Their response has been to evade this problematic… and in the midst to deliver a big fuck you to Marxist alternatives. World-ecology isn’t the only one, to be sure.

It reminds me, Tom, of that thing you’re always talking about with Rosa Luxemburg, her defence of arguments, which I can’t remember the exact formulation of.

Yes, there’s this bit in Luxemburg where she basically says, Marxists should argue in public more because then you’re treating people in Communist or Socialist parties as subjects, as people who can engage; you’re not just treating Marxist thought as the property of six Austrian blokes.

Like a negotiating committee gets together to figure out what’s The Marxist Line, and then supplies it to the people. It’s important to have those arguments publicly—and there’s something really important and illuminating about the kind of reaction that there’s been to your work.

The response to world-ecology is not only generationally split, but also deeply split by geographical location in the capitalist world-ecology. Generationally, world-ecology appeals to younger scholars, for whom a radical curiosity has not been properly disciplined. As I’ve mentioned, world-ecology is among other things a praxis of intellectual disobedience. It challenges the disciplines, not only within the humanities and social sciences but also the “Two Cultures” of the human and natural “sciences.” Here we confront the University’s role in manufacturing consent, one function of which is to silence critiques of its disciplinary structures. Just to pick one example, Capitalism in the Web of Life received its first English-language review in a Sociology journal last year. Happily, it hasn’t silenced world-ecology. The genie is out of the bottle. Once you begin to see Man and Nature and Civilizing Projects as fundamental to capitalism’s geocultures of domination and its dynamic of class exploitation and capital accumulation, you can’t un-see it.

World-ecology arguments are firmly rooted in the anti-imperialist, Marxist tradition of Luxemburg, Fanon, and Wallerstein. There are disagreements within the world-ecology conversation – rightly so! – but it’s safe to say that one or another critique of imperialism is shared by everyone. A great example of geographically proximate but very different contexts is the reception of world-ecology in Ireland compared to England. In Ireland, of course, they immediately grasp the centrality of imperialism. One could never write a story of the “transition to capitalism” in Ireland without foregrounding the English, then British, empire’s bloody interventions. By the same token, accounts of the “transition to capitalism” in England routinely ignore imperialism, and Ireland in particular. This has great significance in history of Anglophone Marxism. For instance, How long did it take the New Left Review to publish something on Ireland? It turns out that we know the answer: between 1970 and 1994, none. And the geographical dimensions of “the transition” take on great significance today, when it is increasingly recognized, especially in the Global South, that something like the Green New Deal is pregnant with possibilities for a new imperialism extractivism.

Yes! Thank you! I mean, there’s still a lot of work to be done on this enormous problem.

I mean, Northern Ireland is essentially occupied territory.

Yes, and there’s a real timidity about having these important conversations about the realities of Empire, and the ongoing realities of colonialism. And I think people feel they don’t want to frighten the horses. And in Britain it’s also a case of “we came so close to winning in 2017, we don’t want to risk saying anything too ‘weird’ or ‘wacky’ like ‘dismantle the so-called UK’”. But people should be saying this! And then people don’t want to analyse their own complicity too much. It’s hard! But then, it’s called ‘the struggle’; it’s not meant to be easy.

It’s also worth noting that Malthus writes his first essay in 1798, at the crescendo of the greatest wave of anti-colonial and proletarian revolt that capitalism had yet seen, including, not just Haiti, not just the radicalisation of the French Revolution, not just Spencian radicalism in England, but the revolt of the Irish in 1798. It’s very important to understand that the Malthusian strand of environmentalism is directly related to civilising projects and imperial projects, and that connection hasn’t really been made.

The question of Empire and the question of Nature are therefore historically joined. Malthusianism isn’t primarily about population; it’s about explaining capitalism’s class structure as the outcome of natural law. This is why Malthusianism – a pillar of bourgeois naturalism – recurs in successive waves of global restructuring and revolt. Today’s Popular Anthropocene and its sacred object, Sustainability, is only the most recent expression of a longer history. The Popular Anthropocene is more subtle than its predecessors, but underlying it all is a kind of black box “gee whiz” reckoning of world-historical transformations, such as the so-called Great Acceleration of environmental change after World War II. Before the Popular Anthropocene, there were three previous “Malthusian moments”: its classic era in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, another around eugenics in the late 19th century, and another coming out of Paul Ehrlich’s The Population Bomb in 1968, immediately reinforced by the first Earth Day in 1970. Those all have in common either worldwide proletarian and anti-colonial revolt against capital, or in the case of the eugenics movement, the great wave of the partition of Africa, the second industrial revolution, and the great wave of Eastern and Southern European migration into the Americas (and above all to the North). Of course, those latter immigrants weren’t yet classified as ‘white’ and “good science” was needed to declare them unfit, at least temporarily, for Civilized Society. So there’s a raced, classed dimension to these Malthusian moments at every turn. (There’s also, to be sure, a violently gendered moment that links intimately to labor migration and webs of life at every turn.) Each Malthusian moment proclaimed some version of “good science.” Just as Sustainability advocates today tell us to “listen to the scientists.” And to some degree, we should. But we can’t sort out the tyranny of science as planetary management from the necessary and crucial scientific research without engaging this long and troubled history of big science, big empire, and big capital. To engage that history, mainstream Environmentalism would need to be reflexive and self-critical; it would need to acknowledge its role in anti-immigrant politics, its distance from working-class environmental problems, it direct and indirect support of neoliberal free trade and military interventionism. Environmentalism, in this light, is overdue for a “truth and reconciliation” moment. I’m not holding my breath.

Covid and the Great Implosion

I think what’s really interesting and this connects quite a lot to live debates that are being had in England at the moment, particularly about Covid. So, there’s a huge push, including from lots of liberals and people supposedly on the left to “close the borders”. There’s this Zero Covid refrain of “we have to close the borders to protect ‘our’ people”—and nobody really wants to look too closely at what they’re saying, and that’s in part that foreigners are dirty and diseased.

Yes.

And it really reflects a lot of the messaging that’s been coming out of groups like Extinction Rebellion, who have specifically—at least in this country; I don’t know if this is the same with them on a global scale—mobilised the idea that climate change, climate collapse, will lead to an immigration crisis, will lead to millions of people pushing at the door of Britain. And they’ve used these arguments very specifically as a recruiting tool. And this interests me, because I’ve been seeing so much of the pandemic and the responses to it from states, the left, and basically anyone in a position of power or influence as almost a sort of dry run. People are getting themselves into place for how bad things are going to get with the effects of ecological collapse (not that those effects aren’t already happening to some extent). And, I guess I’m wondering—is there a way to think the pandemic differently? To be a little glib, how would we think coronavirus in the web of life?

Definitely! There are two parts here. One is about the Fortress Britain (of course, in the United States, Fortress America didn’t need the pandemic, it was the consensus policy of Obama, Trump and now Biden to weaponise the borders). And then there’s the question of what the coronavirus tells us about the ongoing great stagnation of capitalism and the coming implosion.

I’ve often talked about the end of Cheap Nature, which can be read to suggest a gradual, linear and finite process. I’m sure that I’ve contributed to that reading. But that’s not my view. The end of Cheap Nature does not create easy conditions of a civilizational “transfer of power,” where some new mode of production comes in and effectively governs a stationary state. That’s not going to happen. What we’re looking at with the climate crisis is the “end” of Cheap Nature in a very different sense. It’s not a linear “end.” It’s an implosion. I’ve taken to calling the present moment the Great Implosion. This marks the epochal inversion of webs of life from a place of cost minimisation and productivity advance to a place of cost maximisation and productivity decline. This epochal inversion is already taking shape around capitalist agriculture. A recent report in Nature Climate Change indicated that seven years of productivity growth had been lost by 2020 because of climate change already in play.12 And that’s only the beginning. We know we’re headed towards 500-600 parts per million and more intense climate destabilisation in the coming decades.

There’s a parallel here with the crisis of feudalism in the fourteenth century. While the typical Environmentalist frame is Malthusian, the fourteenth-century agrarian crisis wasn’t underpinned by overpopulation. Overpopulation is a bit like saying supply and demand explains economic change – whereas of course it is supply and demand, and population, that needs to be explained. In any event, everyone thinks the late medieval crisis was a Malthusian crisis. It wasn’t. It was a crisis of class power that was wrapped up with a change in climate –a shift towards the Little Ice Age – and the dynamism of tributary civilisations throughout Afro-Eurasia, which meant everyone was breathing the same air, epidemiologically speaking. There was a combination of agroecological exhaustion, of amino starvation—particularly among west and central Europeans—combined with a new disease pool. And all of that was kept along as far as it could go by a class structure of seignorial power over the peasantry.

What happened was first the return of serious problems in the agricultural system, the return of famine on a mass scale, and then the resurgence of disease on a catastrophic scale with the so-called Black Death, which was only the first of countless waves. Signs of fundamental epidemiological change are expressive of the wider relations of class and territorial power in a mode of production.

Scholars like Rob Wallace (in Monthly Review last year) have really done a magnificent job charting this. Mike Davis, as well, has long been charting the connections between pandemics and capitalism. What I would emphasise, in agreement with those accounts, is that moments of dramatically unfavourable climate change tend to ignite all sorts of simmering contradictions, one of which is, almost invariably, epidemic disease.

It’s a recurrent pattern. We can see it after the end of the Roman Climate Optimum in the second century: the next century, there’s a catastrophic plague called the Cyprian Plague in the 250s, and another, after, in the age of Justinian in the 540s. The latter followed on the catastrophic moment of climate change when volcanic activity produced what’s sometimes called the worst climatological year in human civilisation. In sum, climate change, the destabilization of class society, and disease are tightly bound.

As you point out, the pandemic has reinforced tendencies towards the weaponisation of borders. Border policy was not great before the pandemic, to be sure. The convergence of climate crisis and the end of Cheap Nature translates into a stagnation of the world “pie” of total surplus value. Border militarisation works as a political weapon to terrorize and otherwise suppress working classes. It’s part of the ongoing effort, characteristic of neoliberal accumulation, to redistribute first, and grow, second. It’s a prioritisation of plunder over productivity. As the surplus value pie stops growing, politically-enforced redistribution takes over. Essentially, this is Robin Hood in reverse. Environmentalism, which has a chequered past when it comes to migration justice, runs the risk of supporting such border militarisation. Certainly it has done so in the United States since 1970. For Britain, go back and look at the 1972 Blueprint for Survival13, where they call for closing the borders. I worry that the political distance between centrist liberal environmentalism and eco-fascism is not nearly so great as we would like to imagine. James Lovelock—recently celebrated by [Bruno] Latour, may I add—Lovelock says, “build up the British Navy to keep out the African immigrants”. And now Latour comes around and says, “let’s defend the European homeland”. Those are his words.

I didn’t know he’d said that! That’s awful.

Go and look at Down to Earth.14 It’s horrifying, and I’m happy to go on the record around this. In my view, there’s a dangerous tendency – and no more than a tendency at this point. Mainstream Green politics, that maybe at some point might lean towards social democracy, will increasingly be tempted to embrace homeland defence in the unfolding climate crisis. Not that social democracy has a great track record on migration. And, yes, precisely, as you said, it is testing the waters with coronavirus border ‘protection’, so-called.

Network Theory, The Popular Anthropocene and the Flight from History

Yes, the old ‘never let a crisis go to waste’. It’s interesting you bring up Latour, because one of the questions I wanted to ask was going to be around the comparisons between you both, and how you would differentiate between the web of life and something like the network theory that he promulgates? Perhaps a good starting point would be ‘by not saying racist stuff’.

I wrote the first 50 pages of Web of Life as more or less a direct critique of Latour. And when the critics say ‘Moore is Latour’, that makes me think they understand neither Latour nor my own arguments. My position, from the very beginning, was a critique of assemblage thinking, which is really a dressed up critical theory version of empiricism and liberal pluralism. And in Latour’s case, especially, he’s staunchly anti-working class, thinks that capitalism is at best a discursive formation that has no historical-material reality. Indeed, assemblage approaches consistently refuses to name the system, for one, and consistently refuses to advance any historicisation of capitalism.

In that respect, too many ecosocialists are actually on the same page as Latour and his colleagues. They’re also engaged in a flight from history. You can see they mention history, and Malm has written a very effective history of class struggle in the English countryside—but he is completely unwilling to deal with the difficult, messy, historical questions of the transition from feudalism to capitalism, of the transition from one phase of capitalism to another; how capitalism has to reinvent itself not only quantitatively but qualitatively across the longue durée of the modern world. So there’s a flight from history that’s very interesting, and that comes both from the critical theory, anti-Communism of Latour and Haraway and many others, but also from so-called Marxists, who should know better—because I thought the point of historical materialism was that we would be historical.

You mention Haraway quite a lot. She started out at a kind of angle to Marxism, but certainly with an interest in the questions of Marxism, maybe more in terms of the historicised ‘female body’, and how to reject that or move on from it. But I read Staying with the Trouble, her relatively recent one, and I thought: you just hate people! And there’s such a strain of that misanthropy in environmentalism, and I think this connects back to some of what you were saying at the beginning about people sneering at the working class. A lot of working class people live in cities, in densely-populated, messy, complex, historicised and historicising kinds of places, and there’s almost this desire to sort of slough all of that off, forget about it, start afresh, disentangle from the sticky web of relations. It’s apocalyptic!

Or, sometimes, when I read people like Timothy Morton, who’d be another example, of this… when he talks about “ecology without nature”, what he really means is “ecology without humans”. I think he identifies the problem with nature as being that humans reify it. So the problem of nature turns into “nature becomes ‘nature’ because humans reify it and fetishise it, and ruin it”. And, the really refreshing thing about your approach is asking the question: “Which humans? Is it all of them?” It’s a basic question, but people don’t seem willing to ask it or engage with it. It’s incredible the pushback one regularly gets, on Twitter or something, for even critiquing the framework of the anthropocene. And like, it is probably useful for geologists, but it’s not useful for my purposes! What do you think motivates this desire to make all of humanity culpable? What’s going on here?

There’s a contradiction going here with the embrace of Humanity. On the one hand, there’s an emancipatory yearning to see the best of what human beings – living and playing and working in solidarity – can offer. At its best, this is a dialectical humanism of the sort Marx articulates: a philosophy of the human species in the web of life, which through the evolution of class society at once suppresses human possibility and develops the potential for human liberation. On the other hand is a bourgeois humanism. This is a recent invention, maturing in the century or so after 1550. Bourgeois humanism invents Man in a specific way, first of all separate from Nature – and no less significantly dispossessing most humans not only of their land and lives, but of their humanity in Marx’s sense of the term. It’s worth noting that for Marx, the human “species being” was distinctive through its relation with “the rest of nature,” a phrasing that recurs across his work. Bourgeois humanism – and its necessary counterpart, bourgeois naturalism – was not, however, about cultural and geographical dispossession for the sake of dispossession. It was at every turn a Cheap Nature, and above all a Cheap Labor, strategy. It was an accumulation strategy. The ideological work is clear. Man and Nature are class projects, enabled by imperialism, that embody what Sylvia Wynter calls the bourgeoisie’s “over-representation” of itself: Man is Capital, so what’s good for Capital is good for Man.15 This is where I part ways with Haraway and others: the problem is not merely the oppressive dynamics of European “universalism,” but the concrete world-historical “work” of such geocultural domination and bourgeois universalism. What is that work? At the end the day, advance the rate of profit and counter-act the tendency towards surplus capital. Put in these terms, we can begin to understand just why it is so crucial, ideologically speaking, for the working class – and perhaps especially for intellect workers, the so-called white collar working class – to interpret the world in terms of Man and Nature. It actively undermines efforts to reframe, today, the climate crisis as a class struggle defined by carbonization entangled with the climate class divide, climate patriarchy, and climate apartheid. Indeed, in mainstream environmentalism – and especially in the eco-industrial complex of NGOs, government ministries, universities, etc. – to talk about capitalism is, to quote my friend Raj Patel, tantamount to “farting in the lift.” To foreground capitalism in discussions of planetary crisis is to risk being redefined as “ideological” and unreasonable – which is the ideological sleight of hand performed by this master binary of Man and Nature. Here we see the bourgeoisie’s accumulation of what Bourdieu calls “symbolic capital”: essentially, the capacity to render arbitrary relations of power rational and non-arbitrary. The upshot is that the combination of bourgeois hegemony, realized through neoliberal forms of naturalism and humanism, with a popular yearning for human possibility, encourages working people, and especially intellectuals, to frame planetary crisis in neo-Malthusian terms, as a conflict between Man and Nature. Every kind of institutional, technological and organizational mediation can be recognized within such a frame – save for class, imperialism and the Civilizing Project. At all costs, the combined and uneven realities of the climate class struggle must be obscured, the rulers let off the hook, the victims blamed.

Today’s Popular Anthropocene is arguably the highest form of this bourgeois naturalism.16 To be clear, the Popular Anthropocene is the wider discussion of the origins and historical development of the unfolding planetary crisis. It is a geohistorical discussion that the Capitalocene thesis challenges. The Geological Anthropocene is a more specialized field and debate among geologists and earth-system scientists. It’s defined by a search for, and analysis of, so-called “golden spikes” in the earth’s stratigraphy. The Capitalocene thesis takes these geological interpretations as one of several pillars of the analysis. While I’ve identified a certain academic division of labor between the Popular and Geological Anthropocenes, the earth-system scientists have been very happy to blur the lines between them. This began in 2002 with Paul J. Crutzen dating the origins of the Anthropocene to the invention of the rotary steam engine in 1784. This is terrible history. But there’s something more that’s going on. Bourgeois naturalism licenses the “scientists” to opine on world history. Let’s call this the Jared Diamond effect.17 The messy and contentious relations of power, profit and life that underpin the “hockey stick” charts are reduced to abstractly technological, economic, and politics dynamics. A good example are the Popular Anthropocene’s anodyne descriptions like the Great Acceleration to narrate postwar capitalism. The Popular Anthropocene is not at all new. It’s essentially Spaceship Earth rebranded for neoliberalism.

From this standpoint, the Popular Anthropocene serves a crucial ideological function, reinforcing the techno-managerial aspirations of intellect workers and the eco-industrial complex. In other words, it’s a way of manufacturing consent. This ideological work goes all the way back to the first Earth Day in 1970. Its iconic image is the Walt Kelly’s Pogo cartoon: “We have met the enemy and he is us.” The first Earth Day had a counter-cultural flavor, but make no mistake about it, Earth Day was a paradigm expression of centrist liberalism. Radicals rightly denounced it for taking attention away from, especially, the antiwar struggle. And they were right. Less than a week after the first Earth Day, President Nixon ordered the illegal invasion of Cambodia and Laos. The campuses exploded in revolt. That May saw the greatest anti-war demonstrations in American history up to then, where famously National Guards came out and killed white students at Kent State, and Black students at Jackson State. The Earth Day apparatus did nothing. Some environmentalist groups penned a letter. A letter! They had mobilised this extraordinary number—some twenty million Americans—to “save the planet,” but when it came to the scorched-earth practices of Nixonian bombing: So What?

Here is a debate worth having. The Popular Anthropocene says ‘humanity did it’, because of course humanity didn’t do it. Humanity is not an agent. It’s interesting when people say, ‘it’s not about blaming the rich’. Really? We know who is responsible for the climate crisis. They have names and addresses. Taking a properly expansive notion of ecocide, we have a strong sense of the guilty parties. But of course the Capitalocene argument goes deeper. It says that the planetary crisis is a class struggle. It’s about mobilising an internationalist, multiracial, feminist, working class movement that I would call the planetary proletariat. It’s about articulating the connective tissues of proletariat, femitariat and biotariat; about abolish the femitarian and biotarian oppressions that enable the whole system of class exploitation and endless accumulation in the web of life. This is partly an ideological struggle, and therefore also a struggle to gain clarity around the “weak links” in the chains of capitalism’s power, profit and life.

Now, about Morton and Haraway—this is what happens when one abandons a class analytic! And of course that’s the one thing you’re not allowed to talk about in polite society: ‘whatever you do, please do not talk about class power, do not talk about class politics, do not talk about how class politics shapes the extent of acceptable discourse’…

I think that’s right, I find it frustrating. And this question of blame—who is the adjudicator here? Who are we appealing to when we point the figure, like “it was them”? There isn’t anybody there to judge or apportion blame. It’s bizarre, and dare I say unMarxist, this complete appeal to a non-existent external authority.

Yeah, absolutely.

Capitalist Climate Crisis

One thing I’ve been wanting to ask… you mentioned your new book at the start of the interview. Are you allowed to say anything about it?

There are several key strands so I’m not sure I can do it in a nutshell. But let me lay out two guiding threads that might be provocative.

The first concerns climates of class struggle and civilisational crisis over the longue durée. One of the lessons I gleaned when writing Seven Cheap Things with Raj Patel is that moments of dramatically unfavourable climate change over the last 4,000 years have been dramatically bad for ruling classes. That goes for the Bronze Age crisis in the 12th century BCE, it goes for the crisis of the Roman West in the 5th and 6th centuries, it goes for the crisis of feudalism. Dramatically unfavourable climate shifts have, over the past 3,000-4,000 years or so, been dramatically bad for ruling classes. We need to keep that in mind in an era when we hear that it’s easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism.

It also plays out in the first capitalist climate crisis in the “long, cold 17th century.”18 Primarily driven by natural forcing, it was reinforced by the Orbis Spike, which is Maslin and Lewis’s term for the carbon drawdown resulting from the invasion of the Americas and ensuing genocides.19 95% of Native Americans were killed between 1492 and 1610.As a result, soils were left undisturbed, forests grew back, and atmospheric carbon decreased by about 7 parts per million.

The second thread concerns the history of capitalism in the web of life, and especially the ways that its strategies of Cheap Nature formed during the Little Ice Age. To make a long story short, the worst of the Little Ice Age occurred between 1550 and 1700. Historians have long called this the “general crisis” of the 17th century. And it was an era of unprecedented war, economic crisis, political crisis—the English Civil War, the Fronde in France. Capitalism was in effect saved by an audacious, productivist turn towards the colonies. Between 1550 and 1700, we get the sugar plantation system, we get all kinds of other productive enterprises established across the Americas, and we get the modern slave trade to make it all go round. Within Europe, there was also a breakneck pace of proletarianization, much faster than population growth. This has important gendered implications. It’s the era of the so-called witch hunts, as shown in Silvia Federici’s brilliant account of gendered proletarianisation in Europe at this point.20 Taken as a whole, this is the era when the climate class divide, climate patriarchy, and climate apartheid form. Today’s climate crisis is not creating this climate class divide, patriarchy, apartheid; it is being created by it. So that’s one aspect. And climate crises and dramatically unfavourable climate shifts have, over the past 3,000-4,000 years or so, been dramatically bad for ruling classes. We need to keep that in mind in an era when we often hear that it’s easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism.

That thing about the Orbis Spike—you were reading something, Tom, with people suggesting we need to do that again, weren’t you?

Yes, it seems quite a prevalent tendency in parts of ecosocialism arguing for half-earth stuff or kinds of “natural” geoengineering. It says that, because it happened once, dramatic reforestation to reduce temperatures, we should do it again—but planned, and somehow ‘of the left’. Jason mentioned him earlier, but we’ve got a piece coming out in the edition by Rob Wallace, with Max Ajl, around some things connected to this, particularly in relation to veganism and “rewilding”. Trying to do something ‘of the left’ doesn’t guarantee that it won’t repeat aspects of the anti-Indigenous, anti-peasant colonialism of the original form. Is it possible to plant that many trees without repeating that violence? It seems interesting as an argument—that capitalism and imperialism did this; it was bad, obviously—but we can repeat it nicely.

Like the means were bad, but the ends were very good. As if they can be disarticulated! It’s a terrifying strand in recent ecosocialist thought.

There’s also a dangerous tendency to delink the history of colonialism from the history of class formation and the history of class struggle. I would remind people that colonialism, imperialism, is the world bourgeoisie’s preferred mode of class formation. Imperialism is how the bourgeoisie prefers to wage the class struggle. That’s been forgotten in the recent upsurge of settler colonial discourse, which has abstracted class and capital almost entirely. The result has been a kind of ‘clash of civilisations’ theory but from the standpoint of the oppressed, but abstracted from world class formation and struggles. In contrast, the “national question” in the broadly-defined communist tradition was always a class struggle question. It was complex, to be sure, and it’s this complexity – the cross-cutting alignments of class and nationalist politics – merits serious attention. We erase that history at our peril. For example, it seems to me there are instructive lessons to be extract from Lenin’s reorientation to the colonial world following the defeat of socialist revolutions in central Europe. The genius of Lenin after Baku in 1921 was to understand that the center of class struggle had shifted towards the colonial world. The Archimedean lever of the worldwide class struggle was indeed around national liberation and decolonisation. Today, arguable, that Lever is the struggle against the capitalogenic trinity: the climate class divide, climate apartheid, climate patriarchy. Those struggles are uneven, to be sure. They have yet to combine.

You mention E.O Wilson’s Half-Earth. It’s strange that anyone on the left would take this seriously. After all, it’s a call for renewed enclosure. I wonder if some of this neo-Malthusian thinking comes out of the fantastic denial of the contributions of state socialist projects over the last century? When I look at what’s coming with climate change, there’s no question that an unprecedented cascade of socio-ecological disasters will be unfolding with increasing frequency in the next few decades. It seems to me that, if we were wanting to look at countries that were devastated, literally burnt to the ground by the imperialist forces, the reconstruction experience of the Soviets and the Chinese is worth looking at—in a sober way, without romance, but drawing up the balance sheet. And, as I like to remind people, the single greatest contribution to the sustainability and well-being of planetary life in the 20th century was the Soviet destruction of Nazism! We can’t just say we didn’t like how various policy decisions were made and use that to erase real histories of anti-imperialist struggle and egalitarian reconstruction. Look at the experience of Cuba and hurricanes and agroecology! We need to pursue careful assessments of these revolutionary experiments – without romance, without nostalgia, but also with a willingness to learn from the excruciating choices that socialist states had to make.

The Subordination of the Countryside to the City

Another piece we’ve got in our edition is a really strong, interesting piece on Cuban agroecology, and one of its arguments is that Cuban agroecology at least makes some moves in the direction of practically solving the subordination of the countryside and the city. And for Marx and Engels this subordination and contradiction is a problem, but a lot of the Marxist tradition in the West ignores this tendency. And this overlaps, too, with Half Earth stuff—a subordination of the countryside, turn the rural into a carbon sink for continued industrial production and transport in and between urban centres.

Was there not that weird argument about shutting humans out of the countryside, but they can watch it on TV if they want to experience trees or animals?

Yeah, which supposes this weird passivity of people’s pleasures. And I’m thinking about this in terms of those moments in Capitalism in the Web of Life that have this valuable critique of the subordination of the rural to the urban, particularly in terms of the Green Revolution. I was wondering how much that relates to one of the other things that I think is crucial in Capitalism in the Web of Life, and something I think we’ve been talking around quite a lot, which is periodisation—insisting on a much earlier start to capitalism, and refusing to identify capitalism with industrial or fossil capitalism. I’m wondering how these strands come together, especially in terms of capitalist agriculture, across North Western Europe. There’s that Williams thing in ‘Socialism and Ecology’, which has affinities to that refusal, where he talks about sheep and landscape discipline. I’m wondering about this link between periodisation and thinking seriously about the rural and agriculture.

Of course, Williams is so perfect, because he just blows up those myths of the countryside, of how it’s so natural or untouched, so it’s a great point to begin. Indeed, what was happening in England during the first agricultural revolution from the 16th century was something that was happening right across the capitalist world in formation at the time. The disciplining of land was part of the formation of this ruling abstraction Nature, with an upper case N, and the formation of a biotariat: webs of life to be controlled, managed, disciplined, subordinated to the endless accumulation of capital. The ethos of the planetary manager is to be the thinking, planning essence, and the web of life is the non-thinking worker, the biotarian—and that’s a process that goes on simultaneously with the formation of the modern proletariat.

It’s always struck me as very odd that Marxism has largely ignored just how much proletarianisation is overwhelmingly an early modern phenomenon. Indeed, the greatest boom in proletarianisation, both in Europe and also in the Americas, in the form of the plantation proletariat, was between 1550 and 1750. And that was impossible without the creation of the femitariat, this gendered proletarianisation that occurs between 1550 and 1700. Here we can recall Federici’s point about gender proletarianization: that the real basis of proletarianization in these centuries was the redefinition of women’s activity as Natural, and therefore not work. It dovetails with von Werlhof’s point that I’ve reference. Nature is everything the bourgeoisie doesn’t wish to pay for – or in the case of women’s socio-ecological reproductive labor, cannot pay for. Looking at proletarianisation in this light helps us see its connections with not only sexism, but also with the Prometheanism that was its logical and historical precondition. That is – a Naturalised ideology of race and gender was possible only to the degree that Nature had been created, ideologically, as a cosmological domain separate from the Civilizer.